Burroughs, Gysin & Tzara: tracing the cut-up

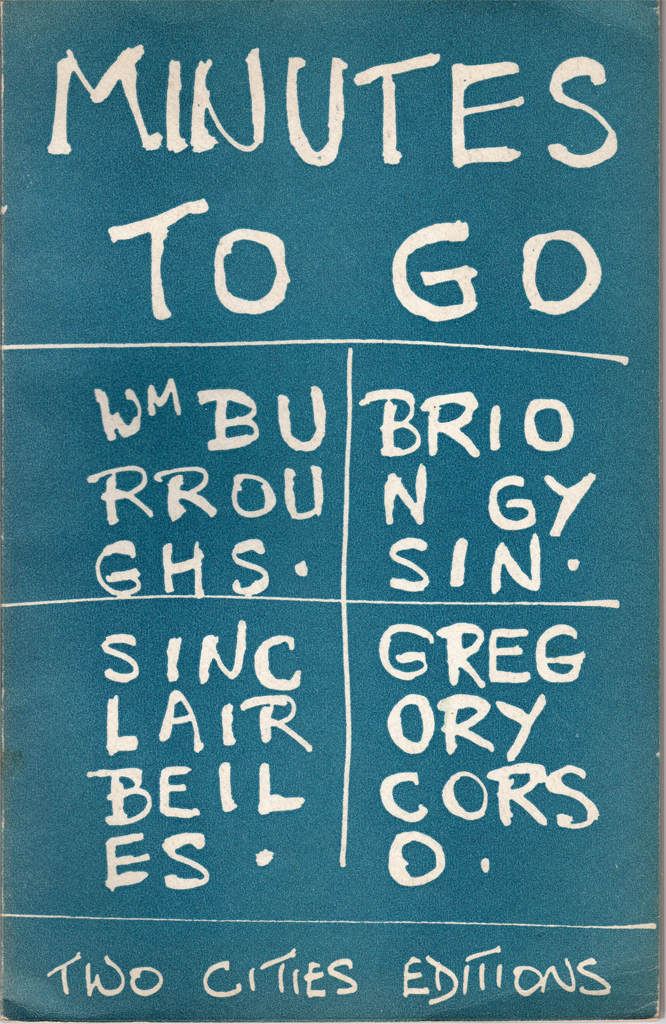

William Burroughs, Sinclair Beiles, Gregory Corso, and Brion Gysin. Minutes to Go. Paris: Two Cities, 1960.

“Tzara did it all before.” –Gregory Corso, Minutes To Go

Perhaps the most influential and widespread ‘technique’ or method in contemporary art and culture has been the cut-up. The use of assemblage and collage in sculpture and cubism, its growing use in literary works from Mallarmé, DADA, Cinema, to William Burroughs, and its steady integration in contemporary music, techno and digital culture.

“The Word is a Virus,” said William S. Burroughs (1914-1997), author of Naked Lunch, which was perhaps the first novel to use the cut-up method to such a shocking degree. Burroughs was a student of Egyptian and Mayan image-based writing systems and saw he power of the word as avisual tool. He used cut-ups throughout his career including his last major work, the Red Night trilogy, with its multiple themes of Egyptian myth, ESP, space aliens, systems of control, an apocalyptic virus, alternative histories with jarring flashbacks, and forays into the afterlife. Burroughs’s darkly humorous routines, and his old Naked Lunch sidekick Dr. Benway make return engagements in his writings. The trilogy consists of: Cities of the Red Night, The Place of Dead Roads, and The Western Lands.

Cities of the Red Night introduces virus B-23, a virus that mutates after a meteor strike in Siberia, destroying 800 square miles of forest and causing the ‘Red Night syndrome’: a souped-up radioactive virus that increases sexual desire (among other side effects) and that eventually eliminates humankind.

It is the human virus. After many thousands of years of more of less benign coexistence, it is now once again on the verge of malignant mutation.” —Wm. S. Burroughs, Cities of the Red Night

Inspired by Norman Mailer’s hypnotic bestseller Ancient Evenings, Burroughs invokes Egyptian deities throughout the final trilogy volume: The Western Lands—a title named after the Egyptian land of the dead.

Burroughs’s use of cut-ups from Naked Lunch to his word-virus trilogy, were admittedly lifted from his life-long co-conspirator Brion Gysin (1916-1986): novelist, visual artist, and inventor of the Dream Machine.

In the early 1970s, Burroughs and Gysin collaborated on The Third Mind, a manifesto of cut-up techniques. A 2010 exhibition, Byron Gysin: Dream Machine, showed the history of their collaborations at the New Museum. In this short interview with Laura Hoptman, the exhibition’s curator, she explains the Burroughs/Gysin experiments and their lifelong relationship.

Cut-ups establish new connections between images, and one’s range of vision consequently expands.” Wm S. Burroughs, The Third Mind

Gysin described his high-energy calligraphy as “the writing of silence.” It was partly based on his study of Arabic, his experience of living in Morocco, and a mystical image-language of his own invention. Gysin’s last artworks were the fiery oversized pages of Calligraffiti (1985)—a giant 55′ screen “based upon the Japanese foldout makemono”—created a year before his death and exhibited for the first time in 2005 at October Gallery, London.

“I am at war with the status quo of society and I am at war with those in control and power. I’m at war with hypocrisy and lies, I’m at war with the mass media,” said artist and musician Genesis P-Orridge longtime acolyte and collaborator of Burroughs and Gysin. In 2018, he combined a series of essays with interviews he did with Gysin from the 1980s. One essay in Brion Gysin: His Name Was Master describes GP-O’s adventures with Antony Balch’s film archive which he helped rescue and restore as Towers Open Fire. This underground cut-up film stars William Burroughs acting out a few of his own routines; ‘We have nothing else so revealing,’ writes P-Orridge, “so experimental, so influential, or so critically vital in preserving such important ‘Beat’ figures and their unfolding, most radical ideas on film.”

Marcel Janco, Portrait of Tristan Tzara, 1919, mixed media, 55 x 25 x 0.7 cm (Centre Pompidou, image: public domain)

“This mask doubles as a portrait of the poet and Dada co-founder Tristan Tzara. Created in 1919 by the painter and architect Marcel Janco (also known in Romanian as “Iancu”), the mask-portrait is an important and rare document of the Dada movement and an embodiment of the so-called “approximate man”—a term that encapsulates many of the movement’s characteristics (“Approximate Man” is the title of a book-length poem by Tzara).”

—Dada’s “Approximate Man”: A Portrait of Tristan Tzara by Marcel Janco by Dr. Eduard Andrei

Roots of the literary cut-up technique can be traced back to the complex Hungarian poet, radical activist, and DADA founder Tristan Tzara (1896-1963). A fact made clear in The Third Mind, and in Burroughs’ 1961 essay: The Cut-Up Method of Brion Gysin.

Tzara’s statement/poem on the cut-up: HOW TO MAKE A DADAIST POEM (1920) was first published in Dada Manifesto: On Feeble Love And Bitter Love of Dada. The City Museum of Strasbourg exhibition Tristan Tzara, poet, art writer, collector: The Approximate Man, was the first ever devoted to Tzara, a seminal figure of 20th century art.

“Freedom: DADA DADA DADA, a roaring of tense colors, and interlacing of opposites and of all contradictions, grotesques, inconsistencies: LIFE.”—Tristan Tzara, Dada Manifesto, 1918

In this short film poet Andre Codresceau reads an excerpt from Tzara’s Dada Manifesto of 1918, “The Bomb”—followed by scholars William Camfield and Marc Dachy, who discuss its impact on the Avant Garde.

The cut-up method is also significant in its influence on twentieth century music with composers Erik Satie, Charles Ives, George Antheil, Edgar Varèse and John Cage and Eno who practiced forms of acoustic montage and electronic sound collage.

Austin Kleon, author of Steal Like an Artist makes note of how the Rolling Stones used the cut-up method for the creation of Exile on Main Street.

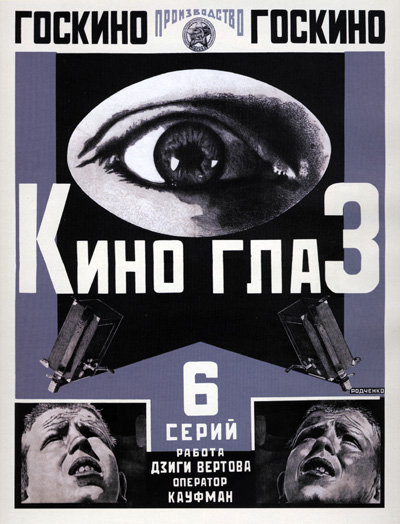

Poster by Alexander Rodchenko for Dziga Vertov’s series of films, Kino-glaz, released in the USSR in the 1920s.

Sergi Eisenstein’s conception of montage revolutionized filmmaking and influenced the development of film language. Dziga Vertov called this method Kino-Eye and developed it during the Soviet era with his masterwerk Man With a Camera one of the most influential movies ever made. In his book Kino-Eye, Vertov describes his filmaking methods:

I fall and rise with the falling and rising bodies. This is I, the machine, manoeuvring in the chaotic movements, recording one movement after another in the most complex combinations. Freed from the boundaries of time and space, I co-ordinate any and all points of the universe, wherever I want them to be.