I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, small press, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If you notice titles are unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at:I arrogantly recommend…

The English Understand Wool

The English Understand Wool

Helen DeWitt

New Directions

This funny novella—it’s only 69 pages long—reads like an homage to French Nobelist Patrick Madiano, who obsessively returns, in his own short novels, to a youth being raised by a shady couple more often absent than not and aloof when home. In the case of Wool, Helen DeWitt’s heroine is a 17-year-old young woman trained and raised by her Maman to have impeccable taste in all matters and behaviors, and significant accomplishment as a pianist. The book’s pivot: Returning to the hotel suite she and her mother have been sharing, she discovers the room empty of her mother’s belongings but the police there. Maman and father are on the run: It seems that the couple who raised her are not her parents. Instead, they stole her as a baby at 18 months and somehow got hold of her $100 million fortune. And her real name is Marguerite. How Marguerite reacts to the news—and the loss of her fortune—says something unexpected but logical about being a person of wealth and taste.

_________________________________________

White Mythology

White Mythology

W. D. Clarke

corona/samizdat

Although White Mythology bills itself as “a” novel, it strikes me as really consisting of two novels about nutty things Caucasian guys do—which is less ominous, perhaps, than a procrustean bed of questionable tendencies baked into a culture (its mythology), which would obtain had we only been given the first part and longest section of White Mythology called “Skinner Boxed.”

“Skinner Boxed” concerns the unraveling of Dr. Ed, a psychiatrist who is spearheading trials of a new drug called Alba, and who—more importantly—believes that all human behavior reduces to chemical reactions provoked by external stimuli. Thus, what one takes as feelings or thoughts represent only conscious awareness of chemical reactions, hence the scare quotes around such words as “feelings” or “thoughts” throughout the book. The implication of this notion is that the concept of free will is a species of nonsense, something Dr. Ed prefers not to consider.

Dr. Ed’s crisis begins with his wife’s absence from home and discovery that she may have surreptitiously been taking the trial drug, as has, it eventually turns out, his indispensable secretary. Revealing the implications of these facts would take this review into spoiler-alert territory. Suffice it to say that more alarming than these discoveries for Dr. Ed is the disappearance of one of his pilot-study patients and the appearance of her angry, distraught husband in Ed’s offices. Things don’t look well for the trial study, or for his marriage and perhaps even with the son whose existence Dr. Ed is uncomfortable acknowledging.

“Skinner Boxed” parodies the rationalist mindset that believes the only good life is one lead by strictly rational methods. What is wrong with that mindset is, implicit in Clarke’s argument, that accumulating rational acts total not to a supreme rationality but to a supreme unreasonableness that is cruel, lifeless, and loveless.

Part II, “Love’s Alchemy,” concerns the rivalry between two brothers, as told by the younger, concerning individual identity, sexual appeal (they mix with each other’s girlfriends), and willingness to break with parental authority. Has great descriptions of hockey fights and a game of capture the flag that includes the use of smoke bombs, bottle rockets, and M-80s. Color me jealous.

Interview with W. D. Clarke:

What riled you enough to write White Mythology, specifically “Skinner Boxed”? Potential perps are plentiful enough: psychiatry, scientific logic (scare quotes optional), marketplace values in human affairs, and so forth? Psychiatry would seem to be the place where human emotions are evaluated for chemical regulation by for-profit corporations. What’s your beef with that?

Riled, eh? Yeah, I guess I was, a bit, then, haha! But that was back in 2001-04 or so, when I wrote White Mythology, and I assure you I am a much happier camper now… 2004 is almost 20 years ago, too, beyond the statute of limitations of the Intentional Fallacy I expect, so anything that I do say here can be taken as reliably ex cathedra as from the Magic 8-Ball for sure, but I suppose that my earlier experience of the major postmodernists as well as Thomas Pynchon in grad school got me to thinking about reason along Weberian and Foucauldian lines.

But it was really Peter Kramer’s book Listening to Prozac that sparked everything for me with “Skinner Boxed”—that, the legacy of the great “Industrial Novels” (especially Dickens’s Hard Times) and Derrida’s “White Mythology,” of course… I suppose I was trying to write a “political” novel without becoming too too tendentious about it, but I guess I did show my hand a bit in that meeting between Dr. Ed and the Alba’s marketing team, when industry plans for future versions of the DSM (the psychiatric Diagnostic and Statistical Manual) come up in conversation…

White Mythology is labeled *a* novel, but as much as I like its two parts I don’t see how they cohere. If anything, what unspoken principle lies behind the transition from the “G-d” of “Skinner Boxed” to the full spelling in “Love’s Alchemy”?

Well, I wanted to try to explore if not comprehend what Derrida’s “Phallogocentrism” generally and the essay “White Mythology” specifically still meant to me some years after being quite taken with it—the idea that reason is always-already bound up in other (political, economic, cultural…) “narratives,” that at its base, reason is inseparable from figurative speech really fascinated me, and I suppose I was looking at different aspects of that problematic.

For all of his supposed commitment to reason, the Dr. Ed of “Skinner Boxed” is as compelled to justify his experiences to himself by telling himself a very self-flattering “story” as the characters of “Love’s Alchemy” are to overshare their pet narratives with others…

And to be even more pretentious about it, I’d say that all of those narratives are bound up within and conditioned by late capitalism’s reifying and commodifying logic. And one of the jobs of the novel—not the only, certainly—is to attempt to reveal or unveil what’s unspoken of or naturalized about those tendencies.

It’s no mistake that James Wood intended a pejorative when he labeled fiction that traces its line back to Dickens as “Hysterical Realism” (somehow uniting such diverse writers as Don DeLillo and Zadie Smith, among others), since in his view the novel should never attempt to do anything like I just described: its sole provenance is social and psychological realism in his view, with I think Henry James being the ideal practitioner of all that. Well, I simply disagree, and instead of arguing about it here I’ll point your readers to the website of the late, great, but underappreciated writer Edmond Caldwell, contrajameswood.blogspot.com –a passion project which was also a tour de force in my opinion (it’s all in the site name!)

I’m wondering if you have any anecdotes about some real-life Dr. Eds you may have met, and in what context? What is it that you think these hyper-rationalists miss, and why?

To steal a line from Milan Kundera’s novel Immortality, I’d been thinking about Dr. Ed for years, but I don’t think I’d ever met him, really. Not with his specific cluster of … issues, I suppose, especially the rationalism mixed with the repressed romanticism. But hyper-rationalists in general, sure! I started off in Engineering Physics, then moved to Philosophy (and English Lit), and in the first two of those fields, it’s kinda hard to miss ’em. One favorite physics professor purchased at least five identical suits, and so over the three years I took his courses I never saw him in anything else, and I found it most endearing: he had bigger fish to fry (superconductivity!) than deciding what to wear to work each day!

But Dr. Ed didn’t crystallize for me until I’d lived a little and learned through experience to empathize a bit more with someone who’d lost something massive like that—a child was stolen from him!—causing him to rather violently wall off his life from the possibility of any future loss or grief. I do empathize with him, as much as I make fun of him. I have little empathy though for the narrator, who quite smugly sees himself (and it’s definitely a he) above and beyond Dr. Ed’s mere station in life. The narrator is the kind of narrator who imagines he’s got the whole world sussed, in fact, and has somehow earned the right to complete, third-person omniscience—as if it were still the nineteenth-century novel’s heyday! So, I must confess to still hating that guy, whoever he is, all these years later….

I love your description in “Love’s Alchemy” of the game of capture the flag that includes the use of smoke bombs, bottle rockets, and M-80s. I’m hoping you can tell me about an actual event this was based on, or is it just a long-cherished fantasy of an ideal battle?

My brother and I actually did nearly incinerate the entire town of Duxbury one particularly dry late summer’s day, but luckily, we got to a fire extinguisher before the fire consumed more than a third of our neighbor’s treed front “yard.” But the game itself is a somewhat rococo elaboration and variation upon a game a 12-year-old friend of mine invented, when I was nine, for a blacked-out basement rec room, in which a lone sheriff comes down the stairs with a cap pistol seeking out a half-dozen hidden baddies.

The problems of White Mythology’s two parts are opposed: In “Skinner Boxed,” Dr. Ed’s problems stem in large part from his lack of empathy for others; whereas in “Love’s Alchemy” they stem from the brothers’ rivalry with each other—they’re too close. What aspects of human experience do you feel most compelled to explore?

I guess—to extend a bit more of what I said above—I like to explore situations that can resolve themselves in more than one direction, and be myself surprised when they go one way rather than the other (in Zadie Smith’s terminology, I am the opposite of the novelistic “micro-planner,” a “seat-of-the-pantser”): In the middle of and again towards the end of “Skinner Boxed,” Dr. Ed is presented with crossroads or possible teachable moments where he could choose to move towards either a rediscovered sense of empathy or back to his protective shell/dehumanizing comfort zone, for example.

I also like to explore self-narratives of Sartrean “bad faith” or “inauthenticity,” how we can lie to others and especially ourselves to keep that ol’ self-esteem machine humming, like pretty much everyone in “Love’s Alchemy.” There’s not much of the “promised” alchemy in that story, though—or love for that matter, except in the two teenaged boys’, Victor and Gerald’s, mutual self-regard, and much of the quoted love poem (John Donne’s “The Ecstasie”) comes in their sections (the title poem is also from Donne, but though it rather cynically denies the very possibility of love, it’s not quoted in the story). But love, and other-centered behavior generally, what the Earl of Shaftesbury, I think, called our natural (if not always expressed) propensity toward benevolence, remains a possibility at the margins of everyone’s consciousness (Gerald even toys with it at the beginning of the story, when he realizes how much he admires his teacher and what he is learning from her, but then decides to poison her plants anyway), even if this particular set of bad faithers choose to listen to and “propagate” a different story…

While humor can tell truths just as well as drama, the choice of humor rather than drama is one the artist makes. Why the rhetoric of humor?

I’m a big fan of Milan Kundera, both of his fiction and of his reflections upon the art and history of the novel. In Testaments Betrayed, his second of such books, he states (quoting Octavio Paz):

“There is no humor in Homer or Virgil; Ariosto seems to foreshadow it, but not until Cervantes does humor take shape. . . . Humor,” he goes on, “is the great invention of the modern spirit.” A fundamental idea: humor is not an age-old human practice; it is an invention bound up with the birth of the novel. Thus humor is not laughter, not mockery, not satire, but a particular species of the comic, which, Paz says (and this is the key to understanding humor’s essence), “renders ambiguous everything it touches.”

So, I guess I am a big fan of such ambiguity, moral and otherwise, like when laughter is not mockery but is mingled with “an almost marveling affection” (Kundera again), and this above all: judgment is suspended and the reader is left thinking about how much he or she resembles Don Quixote or Uncle Toby—or Oedipa Maas or Kundera’s own Tereza and Tomas, for example. For it is that great tradition of high unseriousness which runs from Cervantes and Sterne on through to Musil and Pynchon and Kundera, etc., which for me is just an unending source of delight and inspiration.

And to quote Kundera once more:

Humor: the divine flash that reveals the world in its moral ambiguity and man in his profound incompetence to judge others; humor: the intoxicating relativity of human things; the strange pleasure that conies of the certainty that there is no certainty.

What are you currently working on?

I am in the Interminable Editing stage of a much longer novel (of 220k or so words) about the separate journeys a father and his two adult sons make over the course of the day to meet up at a gun rights rally in small town in Ontario. The father is ex-police, ex-military and is full of regret and anger at his two boys, both massive screw-ups, even as he should be elated that his “Movement,” which he started four years ago, is finally gaining mainstream attention. (I began writing it in 2018, long before the so-called “trucker’s convoy” we were recently besieged with up here in Canada, but as always seems to be the case, history simply overtook me.) It’s called Take Your Guns to Town and it’ll hopefully be ready sometime later this year.

_________________________________________

Seriously Well

Seriously Well

Helge Torvund

The Song Cave

This book-length poem considers the joys of reading, creating, and living—with a recently discovered tumor. Seriously Well is avowedly joyful and appreciative of the “enigmatic art” of writing—“signs / resembling tiny insects,” that “can make the outer world / and the inner imagination / meet.” Writing allows us

To be in contact

with another human being’s

mind, visions and feelings

through letters.

As if a letter

was a magic wand.

Perhaps

the enigmatic in this

is what keeps me

going.

The feeling that such

an almost impossible thing

really can happen.

That by using the language

in a certain way,

you can establish some kind of

direct contact

between that which is existing

in you and that which exists

in another person.

A more laudatory appreciation of literature’s work I can’t imagine. But its admirable achievements are tempered by the fact that, alas, we don’t have world enough and time to explore them all: Time enters into the picture, forcing us to realize the limited period we are granted to appreciate creation.

I suddenly became

completely aware of

the fact

that Death always walks by my side.

I stretched out my hand.

I said: OK; so there you are then.

I might as well shake hands with you,

and accept that you are here.

In this way I included Death in my life.

The gift of creation, in Seriously Well, is represented by a jazz pianist’s improvisation:

Now.

This is the moment.

When your fingertips

meet the keys

nobody knows what

is going to happen.

It’s crucial to point out that, in the moment of creation, “nobody”—including the pianist—”knows what / is going to happen.”

You put your fingers down

and the world is black and white.

And from the black and white

you start to create

colors.

All the sounds

all the tone colors

from green to blue

and from grey to

yellow.

Then, in light of these boundless enthusiasms of color, the diagnosis of a tumor.

A feeling that told me

that when it is darkening around the heart,

and the time is shrinking,

you have to embrace the fear

and give yourself over

to an insane confidence.

A beautiful, sustained meditation on the life-enriching and -affirming places where “the outer world / and the inner imagination / meet.”

Tractatus

Tractatus

Róbert Gál / David Short

Schism Press

Róbert Gál’s most recent book of aphorisms, deftly translated by David Short, are, as usual for Gál, simultaneously philosophical and playful, aimed more at thinking about the problems of existence than offering solutions to them. I’ve chosen a few of his longer passages to exemplify his thoughts’ movements.

3.5 Not everything that is valued is of value, but that, too, changes over time. If the awareness of a value is to be entirely subjective, then ultimately the subject itself is that value, and that applies equally to an object in relation to the objectivity of what is objective. This is a kind of conceptual game, where the part is delineated vis-à-vis the whole and vice versa. What is primary is the point of departure, the point when the mirror is cast, the mirror being at the same time a boomerang. Its three-dimensional distancing and subsequent approaching are inherently linked to an image that is larger, then smaller, then larger again, though it is only two-dimensional. The value of an image resides in the fact that the missing dimension becomes the dominant one and our subjective decision-making becomes decision-making as to the nature of its objectivity. We may see what is objectively dissimilar as subjectively identical and vice versa. And the more convincing this illusion, the more valuable will also be that which we value—and the value is set.

4.1 Beginnings are beautiful for that which they close off: that to which it is suddenly possible to return only as a matter of single-mindedness or a miracle. Imagine, say, a picture, which, leant back against a wall for years, has never said anything to us, then out of the blue it takes the floor to recount the story depicted in it. A story to which we have so far been blind, because it has been part of another story being played out inside us, and we have laid claim to it, resolved to lay such a claim. But suddenly something snaps. Our resolve fails. A previously unknown story starts speaking in its own tongue, which we instantly understand. At that moment we are ready to accept its message, pick the picture up and place it somewhere where it will stand guard over our dream of an encounter between miracle and resolve.

6.1 Enthusiasm is frequently more important than truth, but, just like a truth, it’s either mine or thine, which leads into the problem of its transmissibility. Communicating enthusiasm is, then, an ambivalent act with the side effect of a disgust similar to the disgust that we get from a truth that, for whatever reason, we haven’t needed to know.

I enjoy Gál’s method of looking at the words comprising an idea and taking their meaning and intent to their often-ironic logical conclusions. Philosophy’s methods of generating questions about problems and results, in Gál’s hands, leads to curious insights regarding human existence.

Words

Words

Helena Österland / Paul Cunningham

OOMPH! Press

Helena Österland is a Swedish writer whose first book in 2010 won the Borås Magazine Debut Award. This newer book, Words, consists of three poems/sections—“Was,” “Is,” and “Will”—written in minimalist, incantatory cadences that are rhythmic and hypnotic. The spare vocabulary is repetitious in the manner of a toddler, say, coming to recognize itself as distinct from the world but with a limited number of words learned so far. In more highfalutin terms, imagine Gertrude Stein’s permutations of monosyllabic words mixed with Descartes’ Latin concision (“cogito, ergo sum”) about himself in relation to the world, pared down to its roots in the senses, primarily sight, where sensation equals knowledge. In the case of Words the pared-down world is one mainly of frozen solitude among snow and ice.

I said the word

Snow

I said the word

I had a voice

It was not silent

It was not white

It was not wet

The voice was a voice

I was not the voice

I had the voice

And I believed in it.

The middle part, “Is,” slowly builds upon what it is to “know” something, including oneself by introducing another creature—a raven—to react to in a way that seems to allude to Wallace Stevens’s “13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”:

It is white light

And the grass is white light

And the grass moves

I ofe in the light

I am in the light

I move in the light

And move until I stop

And I stop

I see that there is something

And it is not white light

It is something

It stands in the white grass

And it is black

It stands in the light

It is in the light

But it is not light

I see there is Light

But it is black

I see that it is black

I know the word for it

I see that it is something with eyes

I see that it is something with black eyes

I don’t know what it is

But I see the eyes seeing

I don’t see what they see

But I see the eyes seeing

I don’t know what they see

But I see that it is a raven

—a raven whose eyes the narrator eventually crushes.

But in the last part, “Will,” the narrator sees a (white) fish but tells himself to leave its eyes (and body) alone, leaving us with a contrast in attitudes between forces of light and dark, of innocence and experience. The entirety of Words can be seen as an alternative Genesis, in which words create relationships among other words, our knowledge of them and of ourselves.

Paul Cunningham’s translation does well at translating Österlund’s rhythms and cadences into rhythmic cadences of idiomatic English.

Alindarka’s Children (Things Will Be Bad)

Alindarka’s Children (Things Will Be Bad)

Alhierd Bacharevic / Jim Dingley & Petra Reid

New Directions

The real-life counterparts of the unnamed nations in Alindarka’s Children are Russia and Belarus, in which Belarus is dominated by Russian forces to eliminate all traces of Belarussian culture, history, and language. To capture some of that tension, translators Jim Dingley and Petra Reid have substituted English (for the Russians) and Scots (for the Belarussians). The Sctos language is just unfamiliar enough for English readers to imitate Russian disorientation in the face of a strong dialect. In Alindarka’s Children, the Russian language is referred to as “the Lingo” and Belarussian as “the Leid.” The Leid is under siege and its use is forbidden. Children who speak the Leid are sent to a prison camp where a doctor works who has a “theory” about a bone deep in the larynx that prevents children from speaking the Lingo without an accent. Surgery is occasionally required to remove this “bone.”

The doctor believes that if a spoken language is unclear, then so are thoughts the words are meant to express. Not surprisingly, he has an urge to test his theory on Alicia whose allure for him is simultaneously sexual, predatory, and sadistic; an allure driven in part by Alicia as representative of the ethnic, erotic, and exotic other and in part as a transgressive (for him) hetero assertion of dominance.

As the novel begins, two children, Alicia and Avi, are kidnapped away from the camp by their father and his girlfriend. The father is an absolute stickler for the Leid, refusing to allow the children to speak the Lingo at home and at school, too. The Scottish takes a bit getting used to but sounds English spoken with a broad accent. Songs permeate every page of the novel, like an excessively engaged Greek chorus but whose statements don’t always make immediate sense in the context of the story at any given point but which become clearer as the book goes on. (The book provides a glossary at the end along with keywords defined at the bottom of the page.)

The children’s father (“Faither,” in Scots), who lost his legal parenting rights over language issues, quickly turns out to be dangerously inept and manages to lose the children after stopping briefly to stretch their legs. Faither is alone in his mission to preserve his language and to use his children to both preserve the Leid and refuse to learn or speak the Lingo, even if it will make employment and citizenship easier withing his own country. Avi and Alicia—who seem much better off without him and his even cluelesser girlfriend—are surprisingly resourceful and resilient for being lost in the middle of nowhere. Faither eventually loses his girlfriend and job, too. The children’s mother left Faither long ago over his obsession with the Leid.

Alicia and Avi spend the rest of the novel on the lam, negotiating their way among the perils posed by various adults, almost all of whom demonstrate themselves to be hostile toward the children, even if they, too, like the children, are native Leid speakers. What their fate might be, the novel explores, with compassion, humor, and seriousness.

The Economy Magazine Anthology, Vols. 1-7

The Economy Magazine Anthology, Vols. 1-7

Fanny Howe, Douglas Kearney, Michael Robbins, Rae Armantrout, Ange Mlinko, and others

The Economy Press

“The Economy Magazine was an online literary journal that ran from 2012-2015,” says the back of each volume, and collected here are the poems that ran. The lineup of poets is impressive, as are the range of moods and methods covered, from the mournful to the droll. As a whole, the Anthology makes for a nice introduction to 20 or so contemporary poets—and the design and presentation of the poems also make a good excuse for buying the collection.

Unrepresentative as it is, I’ll let the spirit—the humor and existential exhaustion—of the anthology find expression in these lines from Michael Robbins’s “To Anthony Madrid”:

Distant is our exit, unmoving the traffic;

useful are the implements of a trade;

movies in 3D are intolerable. . .

Long the line for coffee, great my need;

the shaven adepts set their gods in grain;

no right turn on red.

Tideline

Tideline

Krystyna Dabrowska / Karen Kovacik, Antonia Lloyd-Jones, Mira Rosenthal

Zephyr Press

Tideline marks the English language debut of Polish poet Krystyna Dabrowska, admirably translated here by Karen Kovacik, Antonia Lloyd-Jones, and Mira Rosenthal. Dabrowska also won the inaugural Wislawa Szymborska Award (named after the Nobel poet), and one can see similarities in the both authors’ choices of everyday occurrences and objects as topics and their abilities to twist simple language to help us see anew the moral and ethical constraints of common lives. Here are some lines from the poem “Siblings” that demonstrate Dabrowska’s ability to transform an increasingly bizarre situation into one man’s painfully beautiful homage to his deceased sister:

An aged woman dances flamenco.

In her effort a former lightness smolders.

She is tall and slender like a humpbacked heron,

her skirt has frills and ruffles, her cheeks are sunken.

This aged woman dances like she’s still young,

a girl who perished during wartime.

After the show she wipes off the make-up, takes off the wig

and dress, then puts on pants and a jacket

and becomes the person she is off stage:

a male—the dead girl’s brother. . . .

Before the war, they travelled through Europe,

a celebrated teenage dancing couple.

Then came the ghetto, escape, separation.

He told himself that if he survived

it was only to become her embodiment in dance. . . .

Euler’s Gem: The Polyhedron Formula and the Birth of Topology

Euler’s Gem: The Polyhedron Formula and the Birth of Topology

David S. Richeson

Princeton Science Library / Princeton University Press

For some decades now, the Princeton Science Library has reprinted paperbacks in mathematics and the sciences—from astronomy to zoology—written for general audiences possessed of a high school education, a sense of curiosity, and the patience work through the occasional tough spot. Mathematics was never my thang, and I declined to enroll in calculus my senior year in high school. A few years later, when I discovered Martin Gardner’s math games column in Scientific American, I realized how fascinating and—yes—cool mathematics can be in their implications, use, and elegance.

In Euler’s Gem, David S. Richeson, Professor Mathematics at Dickinson College, explains the implications and applications of just one of Leonhard Euler’s many theorems, this regarding just three properties of solid geometric shapes—their faces (surfaces), edges (along which the faces connect), and vertices (the point where two or more edges connect). Oddly enough, no other mathematician or philosopher before Euler had considered edges as a property of polyhedra. The simple recognition that shapes have edges allowed for the insight that V – E + F = 2 in the case of geometric solids with stiff surfaces but equals 0 in the case of such topographic solids as the donut-shaped torus. Richeson demonstrates—with plenty of examples that allow readers to prove to themselves the truth of the mathematical claims—why, how, and where Euler’s theorem works.

Euler’s Gem is more than a series of mathematical factoids. Richeson brings in historical and biographical background to the discoveries made by Euler and other mathematicians to illustrate the human personalities and motivations behind both the discoveries and the errors made over the centuries. (Negative results can present a lot to learn from.) We learn about the history of geometry, its discoveries, proofs, insights, and assumptions—all just by answering the “so what”? behind knowing that V – E + F = 2. These include implications for structures at the micro- and macroscopic levels—from the potential shapes of atomic molecules to graph theory; from the invention of topology (by Euler as a result of settling a debate within a town bisected by a river and island, across both of which were seven bridges, if it were possible to cross each bridge only once) to why the four-color conjecture for planar graphs is true (the conjecture stating that maps may be drawn of multiple countries sharing a border using no more than four colors to distinguish the countries from each other); from determining the area of oddly shaped plots of land, to “prime knots with 16 . . . crossings” (!); and more. Appendix A includes a variety of complex shapes that readers are encouraged to (photo)copy so they can demonstrate for themselves several principles covered in the book. Recommended.

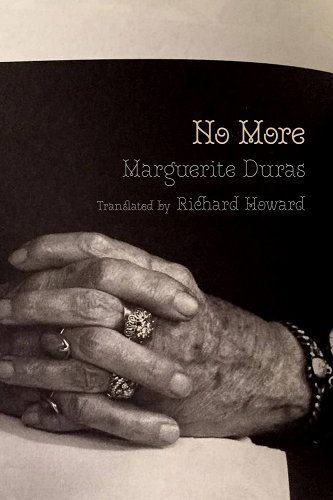

No More / C’est Tout

No More / C’est Tout

Marguerite Duras / Richard Howard

Seven Stories Press

During the last year or so of her life, Marguerite Duras dictated to her young lover, Yann Steiner, her final thoughts. Terser than her usual writing, No More nonetheless conveys Duras’s spirit, showing that remaining intact are also her instincts for all-consuming passion and the blunt, unapologetic observation:

Your kisses—I’ll believe in them to

the end of my life.

Till we meet again.

Again to no one. Not even to

you.

It’s over.

There’s nothing.

End the page.

Come now.

We must be going.

Duras’s repetition of key phrases reminds me of Williams Burroughs’s Last Words, which also, like Duras’s No More, ends with an affirmation of love.

In addition to Richard Howard’s typically fine translation is Christiane Blot-Labareere’s essay, which situates No More within Duras’s oeuvre.

Watch a 1985 interview with Marguerite Duras: Worn Out With Desire To Write.

WD Clarke! Thanks for finding him