I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, small press and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired pavement inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to the Amazon gorilla that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If titles are unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Most of Mr. Bowden’s suggestions are stocked at Book Beat. Thank you for your support! Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at:

I arrogantly recommend…

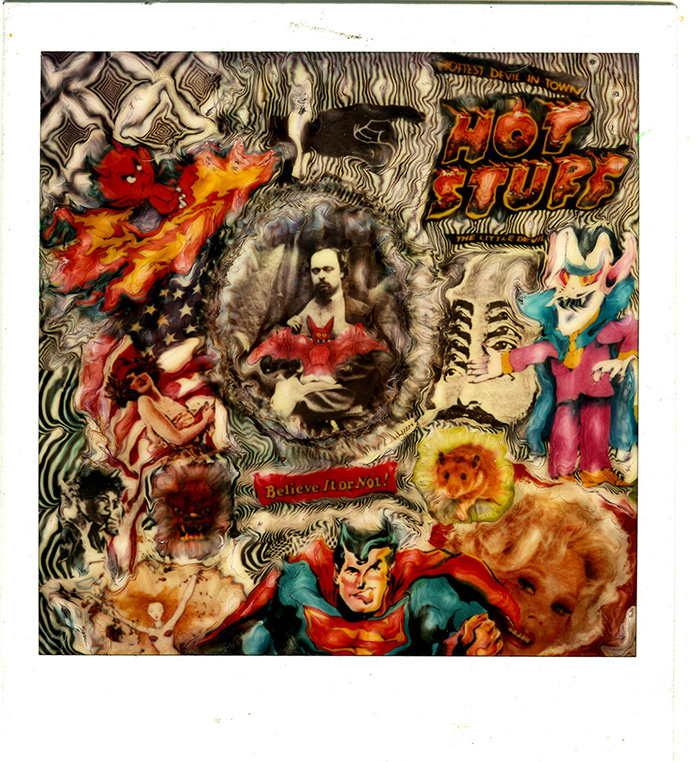

Polaroids

Polaroids

Cary Loren

Edition Patrick Frey, No. 208

The first book (that I’m aware of) to reproduce Cary Loren’s solo early art, unencumbered of the Destroy All Monsters collective, to which he was a heavy contributor and with which a number of obsessions are shared in Polaroids: Replace Warhol’s icy, aloof icons of pop / gay culture with the fantasies of hetero boys, say from 8 to 15, involving monsters, lasers, robots, cute daughters of mad scientists, and astoundingly low budgets. For certain boys growing up in the fifties and sixties, Huxley’s Brave New World had an atomic glow that was simultaneously fascinating and horrifying.

The bug-eyed monster films of the 1950s were often scripted as cautionary tales about the limits of “man’s” knowledge of the universe and the results of hubris. The folly of “rational” thinking mediated via B-films presumably leads to, in the 1960s, questioning the assumptions “the System” (or Establishment) is built upon and interests it serves. LSD and other psychotropic drugs—via the immersive sense of otherness they induce—helped perpetuate ideas of the better life as consisting of more than mere material accumulation. The irrational soul needs tending to, too.

Whatever state Cary Loren’s irrational soul was in one night in 1976, was jumpstarted by an emotional breakdown whose origins weren’t explained until decades later. Finding himself inexplicably hallucinating, he was institutionalized for three weeks and misdiagnosed as schizophrenic—all of which meant, in the institution and afterwards, he was being kept on a steady diet of medications to tame his “schizophrenic” tendencies. Not until 2012 did Loren find out that a person at a party he had attended had poured an entire vial of LSD in his drink.

The images comprising Polaroids were made during his period of recovery. By slowly heating Polaroids in a toaster oven, he mixes the photographic emulsions, blurring the colors and separations among the images shown, an assortment of cut-out photographs of pop and religious icons and mementos from his personal mythology. Polaroids are the tin types of late 20th-century photography: The look of the medium is associated with its time as much as any object captured by that medium. A contemporary tintype will still make viewers think “19th-century” as much as a Polaroid will make them think “1970s-80s.” The medium, what and how it expresses are one. Contending forces of good and evil, love and hate, devotion, alienation: eternal and universal themes of life.

The images comprising Polaroids were made during his period of recovery. By slowly heating Polaroids in a toaster oven, he mixes the photographic emulsions, blurring the colors and separations among the images shown, an assortment of cut-out photographs of pop and religious icons and mementos from his personal mythology. Polaroids are the tin types of late 20th-century photography: The look of the medium is associated with its time as much as any object captured by that medium. A contemporary tintype will still make viewers think “19th-century” as much as a Polaroid will make them think “1970s-80s.” The medium, what and how it expresses are one. Contending forces of good and evil, love and hate, devotion, alienation: eternal and universal themes of life.

The still photographs with unmixed emulsions are staged and costumed: The home movie versions of the TV screen shots some of the other Polaroids depict: The vixen, the femme fatale, at a moment of viewer enthrallment, in opposition to the creatures of the screen.

The reproduction of the images and the paper their printed on are both excellent. You can almost see the acid trails across the images’ surfaces.

Interview with Cary Loren:

When you created these Polaroids under the influence of acid, did they seem at the time like surrealistic reactions to the world around you or were you trying to render realistically what you saw and felt?

I wasn’t aware of how the LSD affected me because I didn’t know I had taken any. Much time had passed since these were made, and I never considered that connection until the book’s editor Cameron Jamie brought this up during the interview. At the time, making collages with a Polaroid was an alternative to fixing collages on paper or making a “straight” photograph. I was trying to depict images in a realistic way and manipulated the in-between spaces to merge the edges to create a more connected image.

Certain icons recur in your pictures: Frankenstein, Dracula, the Werewolf—horror icons from the ‘30s and ‘40s—and bug-eyed monsters from SF films of the ‘50s and ‘60s, with a smattering of beautiful women throughout, mainly femme fatales. What did you like so much about these films? You keep re-documenting icons from your life going back, say, 60 years. I’m assuming they must trigger something inside you. William Burroughs once called his work a “mythology for the space age.” Do these pop icons function in a similar way in your work?

I’m still fascinated by monster movies, silent films, Victoriana and sixties pop-culture. I like the “twilight zone” and weird dream consciousness that these images and times evoke. Recreating the art was a process of self-mythologizing, creating something from the past. Making art is sometimes a way to deal with the chaos of the world in a positive way -to arrange and order it. Burroughs used the collage technique in his writing to splice into reality and that was a definite early influence, especially for it’s campy satiric style, and the nightmarish world it explored.

Something that collage has in common with other photographs here is that they’re both emphatically staged—the elements of the image and their positions tightly arranged. Microwaving the Polaroids to blend the colors opened the results to haphazard outcomes, an element the staged photographs don’t seem to allow. What makes you feel that an image is better suited to staging than chance processes?

Photography is an art of chance to various degrees. The staged photos in reality had some theatrical direction or theme planned ahead. They were made like stills for an unmade movie and involved models and sets. I was usually also shooting 35mm film and using the Polaroid as a guide or “notebook” for the shoot. There’s more control and chance arranging happening with collage and the final result is usually surprising and transformative. Collage mimics reality in a strange way and can be a parody and practice of imagination.

How has your approach to collage changed since the works in Polaroids were created, and what has remained consistent?

With Polaroids you could move and blend images in an organic hands-on way. That kind of direct manipulation in photography is probably gone for good. The chemistry of the Polaroid has changed and is not the same. I’m using more drawing and painting techniques to create backgrounds as a space to “hold” the cut images. The backgrounds also help define what the collage will be about. I’m also still very interested in how images circulate in books, zines and printing.

It seems that even if today you can take from the internet, your collages still have images that look like magazine cut-outs—is that a look that you deliberately seek out?

Polaroids and collage have a presence that digital or online reproductions can’t compete with. There’s a long history of cheap magazine cutouts from scrapbook diaries and how collage connects to all the baggage of surrealism -it’s a very loaded, misunderstood, ignored medium, and that’s partly why I’m drawn into it.

Do you have any other books of your work coming out? As much as I like Polaroids, I feel like I’m 45 years behind what you’re doing. Also, any more shows coming up?

I’ve been working with a small publisher on a miniature book and am thinking of self-publishing a zine of silk-screens. My next exhibition is in a group show of artists zine makers from North America and that will open next fall at the Brooklyn Museum.

Bruges-la-Morte

Bruges-la-Morte

Georges Rodenbach / Will Stone

Wakefield Press

It was as if the frequent mist, the veiled light of the northern heavens, the granite of the quays, the incessant rain, and the bells passing through had together influenced the very color of the air—and also in this ancient town, the dead embers of time, the dust from the hourglass of the accumulating years, over everything, its silent legacy.

That was the reason Hugues had wished to seek refuge there, to feel his final energies imperceptibly and irrevocably silt up, sucked down beneath this fine dust of eternity which too lent a grayness to his soul, the color of the city.

A mournful tale told simply, each chapter a step in the emotional evolution of the 40-year-old widower Hugues Viane. His wife having died five years earlier, Hugues moved to Bruges both to escape where they had spent much of their lives together and because Bruges had struck them both as a melancholy place, which Hugues feels is apt, given his depth of mourning for her. First we meet Huges and find out how he came to be in Bruges; then are shown his walks through town; his first sight of Jane Scott, the dancer with whom he will become infatuated and the spit and image of his deceased wife; how they come to meet; etc.

Originally published in 1892, Bruges-la-Morte introduced the technique of including in the book photographs of the places either described or forming its emotional shape, a technique often associated with the late 20th-century writer, W. G. Sebald, with which the distinction between fiction and nonfiction is blurred, heightening the story’s sense of lived reality.

Hugues, as it turns out, does not love Jane but merely what she represents to him:

All he wanted was to perpetuate the illusion of this mirage. When he took Jane’s head in his hands and drew it close to him, it was to look into her eyes, to search there for something he had seen in another’s: some nuance, a reflection, pearls, a flora whose root is in the soul—and maybe which were floating there.

Of course, events come to pass so that Hugues and Jane become disenchanted with each other, Hugues in particular with the folly he’s committed in hoping through Jane’s resemblance to imagine himself again with his dead wife. The novel’s second half deals with the slow, painful, and mutually recriminative dissolution of what had once been a mutual passion.

“One would think all cheerful plans are a challenge! Overlong in preparation they allow ample time for fate to switch the eggs in the nest and we are left to brood on sorrows.”

Creepy

Creepy

Lee Sensenbrenner & Keiler Roberts

Drawn & Quarterly

When my daughter was in early elementary school, I used to tell her that pencil erasers were the thumbs of bad children. Who compiled the list of bad children in the world? Santa. His elves handled the manufacturing. That said, this short story about a totally normcore woman—save for one unpalatable tic not dissimilar in spirit from what I used to tell my daughter—serves as a good cautionary tale for children too enrapt by their screens for their own good.

Beyond

Beyond

Horacio Quiroga / Elisa Yaber

Sublunary Editions

“Everything you do is useless.”

—from “The Call”

The eponymous “beyond” of this collection of eleven macabre stories refers to that which occurs or exists after death—whatever that may be—and that which seems ordained by death or mere Cosmic whim. “Beyond” is the shudder-inducing unknown eternity, which seems likelier spent in further torment than cessation of sensation. Little has been published in English translation, Horacio Quiroga (1878-1937) was a Uruguayan writer of the uncanny, whose own biography was a master study of morbid concision. According to the blurb on the back of an earlier translation of Quiroga’s stories, The Decapitated Chicken (University of Texas Press, 1976),

As a young man, he suffered his father’s accidental death and the suicide of his beloved stepfather. As a teenager, he shot and accidentally killed one of his closest friends. Seemingly cursed in love, he lost his first wife to suicide by poison. In the end, Quiroga himself downed cyanide to end his own life when he learned he was suffering from an incurable cancer.

To paraphrase Kafka, there is hope, but not for Quiroga’s characters. Think of Poe in a rain forest amid lurking dangers and rotting vegetation.

Story topics in this collection include a double suicide; a form of vampirism as miserable as its European cousin’s; spinal paralysis from a fall in a rainforest miles from help; insane railway workers; parents unable to save their children from death, and so forth. At least during the Halloween season, this stuff should be flying off the shelves. Elisa Taber renders Quiroga’s prose into contemporary, idiomatic English, keeping his voice fresh and the feel of the stories new rather than as descriptions of yore, and offers an Afterward that contextualizes Quiroga’s contribution to world letters.

The Forest

The Forest

Thomas Ott

Fantagraphics

Thomas Ott is a master of scratchboard art with the ability to unspool wordless, “Twilight-Zone”-like tales of the weird, morbid, and unsettling. As with any other art involving carving and scraping, scratchboard is a subtractive process, making errors indelible from the work—and if there are errors here, my eyes have missed them. The predominantly black tones of scratchboard images are aptly suited to the stories Ott tells and are both strange and beautiful, in proportion to the needs of beguilement.

The Forest is a short tale both bittersweet and haunting. In the tale, a tween-aged boy leaves his house, which at the moment is hosting a wake. Some fresh air will be good. And, in a way, it is, because it tells what we need to know about the wake. Overall, the story, told across 25 pages, is eerie, mournful, and—loving.

The Impersonal Adventure

The Impersonal Adventure

Marcel Béalu / George MacLennan

Wakefield Press

The broad outlines of the action in The Impersonal Adventure are given succinctly on the book’s back cover: “A traveling businessman decides to tarry in an unnamed city, dons a new name and profession on a whim, and rents a room in a mediocre hotel on the island lying at the city’s edge,” and “wanders through the streets of unvisited storefronts and abandoned offices.” Decay, rot, isolation: decadence central. A book in which no one is who they seem to be, and every action has multiple, even contradictory, implications. “The denial of the irrational, which it facilitates our relations with our fellow men, in no way dispels the inscrutable mysteries surrounding us,” Béalu’s narrator asserts late in the novella. Social relations are built upon assuming rational explanations for material events, no matter how rare or unlikely. What cannot be explained is ignored.

These explanations, like the somewhat confused ones of [the characters] Squint and Corinne, provide me with a different version of the same enigma without supplying the key. The illuminate things from another angle without revealing the underside—which is all that matters. But I’m beginning to get the impression that perhaps the truth only wears the mask of mystery so as not to admit defeat, surrounded on all sides, like the cornered beast who, under the upraised knife, send out such a pathetic look that the armed hand needs more willpower to merely lower itself than that required by all the trappings of the hunt.

Although Béalu cites a passage from Melville’s Benito Cereno as the novella’s epigram, it could as easily have been a passage from Akutagawa’s Rashomon, such is the nature of narratives that ask rational deduction to unravel mysterious knots.

A significant portion of the banality of mystery—its everyday quality—is comprised of multiple masks every person wears in the presence of others. Duplicity is unavoidable:

I divine a thousand avid papillae under the cold and meek mask. Souls condemned to sterility believe in the necessity of interposing an impassive veil between themselves and the world, thinking that they’re concealing their cruel egotism, but little by little the features of greed show through, sometimes exploding at the end of their lives into those ferocious grimaces that populate padded cells.

Unlike Thoreau observing, from a distance, the “lives of quiet desperation” of the miserable masses, the narrator of The Impersonal Adventure sees in others what is true of himself. At one point, when confronted by others for his suspicious behavior,

I own up to my true identity, recount my return to the island, state my intention of remaining (without, of course, mentioning my real motives). The better to convince him, I turn on the tears, sniffle maybe a little too loudly.

True statements of identity and intention are not the same as statements of motivation, which remain unrevealed even during a moment of “telling the truth.” To what degree is the narrator masked even to himself?

BÏK§ZF+18: Simultaneities and Lyric Chemisms

BÏK§ZF+18: Simultaneities and Lyric Chemisms

Ardengo Soffici / Olivia E. Sears

World Poetry Books

Ardengo Soffici was an Italian artist, writer, and early contributor to the development of Italian Futurism during the 1910s. Although he eschewed the yoking of the arts to politics—which lead to ongoing arguments with Futurism’s main voice, Filippo Marinetti—Soffici’s politics did tend to the conservativism of the time. And after the Modernist breakthrough that the poems of BÏK§ZF+18 represent, he broke from the avant gardes of any stripe, reverted to writing traditional verse, and eventually even tried, decades later, to re-present the poems in this collection “restored” to conventional forms—including standardized punctuation and typography. Translator Olivia E. Sears (and founding editor of Two Lines Press) takes on the charged task of translating the formally radical poetry of this proto-fascist.

The characteristics of Futurism that Soffici embraced included its fascination with “energy and speed” (per Sears), which was expressed through words streamlined of articles, punctuation, and other verbal and visual artifacts of language that slow down the rush of images and events described.

In this excerpt from “Poetry,” I hear Whitman as told to Baudelaire, foretelling Ginsberg: The long-breath lines, the morbid imagery representing false ideals and idyls—although the decadence marking culture’s death without promise of a breakthrough to the Fascist idea of renewed “vigor” belongs to Soffici:

One could say that we have never died These pale worms might just be blond hairs and the old ironies a lie told on billboards blooming on cemetery walls

Just one turn of your golden eyes (I’m not speaking to a woman) and there goes any hope of repose an orderly sunset and diplomatic tact in liquidating love affairs

The poem “Boredom” (which, like “Poetry,” is from the book’s first part, Simultaneities), also conveys the ennui typical of Decadents from the time:

No more hope of living

In the absolutes of joy or the splenetic despair

Free of life’s contingencies

The prisms of the times and our sensibilities

Dies in the details stranded like the syphilitic sun

(Always with the syphilis, these Decadents. But the conservative Soffici doesn’t make recourse to abundant intake of sex and drugs here to ward off the boredom.)

The “speed” part of the Futurist equation is amply evident in the book’s second half, Lyric Chemism, in which typography itself and its placement are key to recreating the hubbub of big city life, in which messages strike pedestrians from every angle—on signs, pamphlets, and placard; shouted from vendors and freaks; and visually blared from storefronts. Bonus points to Sears and the editorial and design crew at World Poetry Books for recreating the fonts used by Soffici, which are especially crucial to this part of the book, and which Soffici threw himself into with gusto.

While it’s too bad that Soffici’s political decisions adversely affected his subsequent works (his experience as a soldier in WWI drew him even further to the right), at least he gave the world one solid work that peeked into the possibilities offered by a world he chose to ignore.

Ça Val Aller

Joana Choumali

Nazraeli Press / One Picture Book Two Series

Joana Choumali develops photographs taken with her iPhone onto cloth, on which she sews colored threads to accent or distort the pictures. The impetus for this monograph, Ça Val Aller, was a mass shooting near where the photographer lives. The act of sewing onto the photographs, the time it takes to do so, adds a meditative, tactile quality to a snapped moment. This edition of 16 reproductions also comes with a signed and sewn picture from the series. The One Picture Book Two Series from Nazraeli Press publishes brief monographs in editions of 500 by photographers from around the world. In a series devoted to top-notch works, some stand out from their peers, and Ça Val Aller is one of those works.

Poems of Masuo Basho, Yosa Buson, Kobayashi Issa, and Taneda Santoka, and Six Phrases by Hatano Soha

Poems of Masuo Basho, Yosa Buson, Kobayashi Issa, and Taneda Santoka, and Six Phrases by Hatano Soha

Anthony Opal, translator

The Economy Press

Translator Anthony Opal presents a brief history of Japanese haiku in these five pamphlet-sized chapbooks, elegantly and sparely designed to match the deceptive simplicity of the poems. Each pamphlet is devoted to a separate poet, beginning with Basho (1644-1694; his Western contemporaries include John Donne, Ben Jonson, George Herbert, John Milton, and Andrew Marvell) up to Hatano Soha (1923-1991; with, say, Allen Ginsberg as his contemporary).

The presentation of each poem begins with its rendition in Japanese characters, followed by a transliteration into the Western alphabet, and finally Opal’s translation. Given the sparseness of the form—a handful concrete nouns whose juxtaposition by each other evokes the visual, aural, and tactile elements of a small moment—the evolution of the form, how each poet shapes the tradition, is subtle.

Here is Basho on returning to his mother’s home after her death, finding his umbilical cord that she had saved:

At my old home

weeping over my umbilical cord

the year ends

Often the haiku feel like a compressed sonnet: the first two lines acting as the octave, with the third acting as something like the answer. Here are a few lines from Hatano Soha:

The goldfish bowl

I dropped

a flower on the pavement

Overall, an excellent group of translations, highly recommended. Available singly or as a set.

Handlauf: Neues and Nachgereichtes [Handrail: New and Earlier Works]

Handlauf: Neues and Nachgereichtes [Handrail: New and Earlier Works]

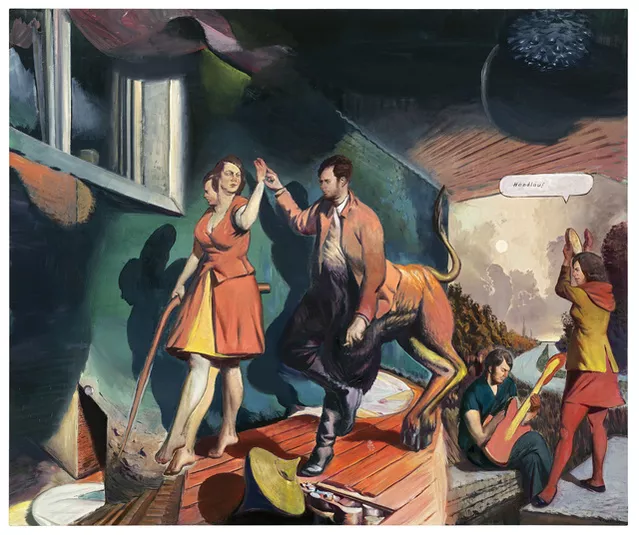

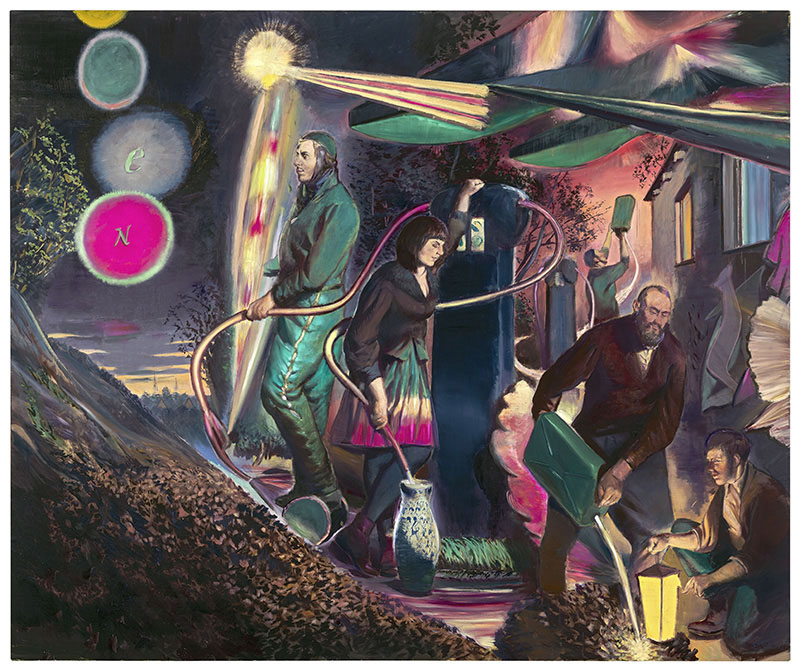

Neo Rauch

E. A. Seemann Verlag

“[A] handrail is . . . something that helps us maintain our balance, isn’t it? We hold it for security.” —Neo Rauch.

Born in 1960 in East Germany and raised by his grandparents after being orphaned (they were only 39), Neo Rauch’s art school training was more classically oriented than that of his Western counterparts. Of course, East Germany was not a place for an imaginative artist who liked to examine life’s ambiguities—ambiguities do not officially exist in fascist regimes. But the fall of the Berlin Wall certainly must have helped his career, which has been internationally successful.

This collection of Rauch’s paintings from 2020 and earlier shows his works in characteristic form: elements of Dutch and Flemish Renaissance paintings are there—old European buildings, figures painted in serious attitude (but looking collaged into place) and arranged in space in a that way creates a sense of allegory—but an allegory of what is always the mystery of Rauch’s paintings.

The ambiguities and hermetic symbolism implied in his work remind me of paintings by Mark Tansey and Mark Ryden, with a palette like Tansey’s but far busier scenes and not as commercially polished as Ryden. Is it Surrealism? Plenty of visual evidence suggests so: The multiple planes across which the visual narrative unfolds, the shifting or incomplete perspectives, the use of mythical-seeming creatures and symbolic-seeming artifacts. But, for me, it’s the arrangement of the figures—their poses and attitudes, their engagement with or dissociation from their environment—that hints of subterranean semantics of a, say, Jungian character rather than Surrealist.

The Double Dealers

The Double Dealers

Chandler Brossard

corona/samizdat

Reprinting Brossard’s novel from 1960, now with the original title, the premise of The Double Dealers is that society allows two forms of social expression: honesty—rewarded with prison or asylum time—and hypocrisy—rewarded with social acceptance and prestige. Into this arena, a group of friends and acquaintances—middle-class would-be sophisticates—play out the extremes of human behavior, per Freud and Nietzsche. Cocktail party posturing, petty crimes for kicks, female sexual aggressiveness, miscegenation—a lot of heady subjects in 1960 in a short book. A sort of Jim Thompson-of-the-populist 10¢ novels of social commentary bathed in Modernism lite, The Double Dealers examines the friends’ entwined lives and assumes that no one is simply as they appear, let alone innocent.

While the action is often salacious and sensational, Brossard gets good marks for trying to break stereotypes (even while reinforcing others), granting his characters an agency both non-conforming and realistic, and using a vocabulary every bit as basic as that used by Simenon for his Maigret novels. One of the women—usually shy and demur—upon seeing a handgun for the first time, strokes and kisses its barrel, then demands to take the lead when the group she’s with decides to knock over bowling alley. Another character’s demonstration of sanity is his involuntary incarceration in a sanitorium, being true to himself rather than the social dictates of mediocrity. There’s a ballet-loving Black man with a PhD in English poetry from Oxford (he quotes Herrick at a party), who invariably finds himself seduced by white liberal women. But ultimately, Brossard’s characterizations strike me as too tied to his era’s dogmas of conventional psychology to successfully convey the nuances of human behavior, which offers more than mere duplicity. If John Updike had applied noir techniques to his novels of suburban chicanery, you’d have Brossard in a nutshell.

The Mars Review of Books

The Mars Review of Books

Volume 1, Issue 1

marsreview.org

The Mars Review of Books hopes to correct core problems many reviews currently indulge in. According the review’s editor, Noah Kumin, “(1) Traditional publishing is a fandom. (2) Book reviewing is a Ponzi scheme. (3) All writing is prayer (and if you use the wrongs words, your prayer goes unheard).” That is, book reviews tend to limit themselves to what the five major publishing houses offer; publishers advertise only in places that positively review their books—by writers looking for publishing deals; meaning (3) reviews tend to be published more for their ability to sell than their ability to say.

In response, Mars intends to include different and new media outlets who products usually go unnoticed in the mainstream; select books and reviewers based on their own merits rather than as steppingstones to something else; and choose quality of thought over its money-making potential.

Thus, Christian Lorentzen’s “Which Way, Western Author?” explores the deeply inane world of an author named Bronze Age Pervert, N. E. Davis tackles the problems of nuclear fusion, Matthew Gasda reviews Catherine Liu’s takedown of the cancerous professional managerial class, and William M Briggs casts a libertarian eye on the brief history of COVID-influenced policies. Weird and obscure areas of internet culture are explored by Reid Scoggin and Anika Jade Levy in their essays on “The Warez Scene” and “Angelicism,” respectively.

I like the magazine, am about to begin the second issue, and have subscribed for a year. The editors have succeeded, at least with the first issue, to (1) provide a set of reviews about topics and from media that are usually ignored and therefore (2) won’t be big money makers for publishers or reviews, despite (3) having something to say.

Liberties: Culture and Politics

Liberties: Culture and Politics

Volume 2, Number 4

Liberties Journal Foundation

Liberties is a newish quarterly publication devoted to long-form essays on various topics in, as the journal’s subheading indicates, contemporary culture and politics, with some poetry. Except for the poetry, the essays are mainly written by generalists with academic backgrounds in history and philosophy. No ads.

The specific issue under review, published for summer 2022, includes reactions to and assessments of Putin’s war in Ukraine, including by Ukrainians, with some poetry. (Oksana Forostyna, Valzhyna Mort, and others.)

Philosopher Justin E. H. Smith critiques the area of virtual reality and artificial intelligence as often based upon unexamined assumptions about the world by professionals who should know better. (Smith’s critique highlights the frequent culprit behind bad ideas that are initially well-intentioned: Unexamined assumptions.)

Jaroslaw Anders’s “An Open Letter to an Enemy of Liberalism in My Native Land” is addressed to Ryszard Legutko and his “works of a declared Polish anti-liberal, a philosopher, an educator, a former minister of education, a politician of the ruling illiberal Law and Justice party, and a member of my own generation.” Far from parochial matters of only a slavic nature, the “Illiberal authoritarianism” Anders addresses is in world-wide pandemic, and many of the matters Legutko complains about are echoed by Trump and his adherents. . . And Helen Vendler parses a poem by John Donne with her usual astuteness that joins academic rigor to mood.

Overall, the contents of Liberties are intelligent and thoughtful, devoted to preserving what is best about open, democratic societies—a sense of amiable moderation in all things, thought and deed, freely expressed.