Kin

Kin

Miljenko Jergovic [Russell Scott Valentino, trans.]

Archipelago Books

Kin is a fictionalized account of the author’s Serbian / Croatian / Yugoslavian / Christian family history, extending to the early 20th century and working forward—times of national and international tensions, international and civil wars, wars where being a person with the wrong combination of ethnic / religious heritages in the wrong neighborhoods could have fatal consequences. Croatia endured invasion by the Nazis, followed by Soviet oppression, followed by the war in Sarajevo. Not surprisingly, charting the complexities of the past hundred years as endured by just one family living in just one city with this particular Eastern Europe mix of ethnicities, religions, and political affiliations takes 900+ pages.

Kin is a web formed by the interconnected and overlapping lives and influences of Jergovic’s extended family, beginning with the author’s great-grandfather, Karlo Stubler, strong-willed and stern. Less a novel than a collection of, um, related short stories and novellas about one family’s history in relationship to local political geography over the course a century, Kin illustrates how consequences ripple across the generations and along chains of kinship, whether those ripples be formed by actions within the family or imposed upon it by social conditions of the time.

Overshadowing much of the book are Jergovic’s grandparents, Franjo and Olga, as well as his troubled relationship with his mother, who didn’t begin to attempt to raise him until he was 10. Franjo and Olga, however, are a broken couple, split by Olga’s encouragement of their son, Mladen, to enlist in the German army, during WWII, rather than join the resistance because she thought the Nazis would win the war, which would improve Mladen’s odds of living. Franjo was against it, thought Mladen was better off with the resistance, but made no effort to stop his son from by being swayed by Olga. The consequences of that decision haunt the days, years, and decades following Mladen’s death in combat for the German army. This regret in an area where one could point out, several decades later, who among the currently living, unpunished, killed who during the war in Sarajevo.

The novel’s last section matches photographs of places and family members, accompanied by a few paragraphs describing what is shown. Most are poignant and sad. The caption to a photograph of one family member encapsulates the novel’s themes and mood particularly well:

“The wartime devastation is visible on the face of Home Army First Lieutenant Rudolf Stubler. Eternal polytechnics student in Graz and Vienna, gifted violinist, lover of music, poetry, and mathematics, skilled beekeeper. Women loved him. A delicate soul, sweet and smart, when this picture was taken at the Winterfield Photography Studio, he was twenty-four years old and had not worked a day in his life. . . He had grown thin from fear, as he lay down every evening with taps, turning his back to the sleeping Home Guardsman, and instead of the barracks wall before his face, Rudi found himself face to fac with this own death, who would say: You won’t make it.”

As I write this, Kin has just been longlisted for the 2022 Dublin Literary Award. Congratulations are due to both author Miljenko Jergovic and translator Russell Scott Valentino, the latter who gracefully performed an enormous job.

In a Bucolic Land

In a Bucolic Land

Szilárd Borbély

NYRB Poets

Szilárd Borbély’s In a Bucolic Land describes growing up impoverished in Hungary during the ‘60s and ‘70s as a member of a despised religious minority among despised minorities living under the thumb of atheist Soviet Union. The “bucolic” of the book’s title is ironic not elegiac—Nature is as brutal and unsympathetic as parents toward their children and the community at large toward each other as everyone struggles to exist at mere subsistence-level.

Borbély names as “the gods” the indifferent forces of whim and fate that seem to decide the lives and deaths of people toiling to get by. This is a tendency I’ve noticed among European writers unconvinced by Romantic, transcendental swooning over brooks and glens. Instead, writers I’ve recently reviewed—such as Jean Giono and Adabelt Stifter, and Inès Cagnati—illustrate the brutality needed to merely survive, where “Christianity” is a patina barely covering the avowedly pagan world the characters maneuver within.

Inès Cagnati in her novel Free Day, left an impression of poverty that has stayed with me since reading it: To send her daughter to school, where she has won a scholarship, the mother must sacrifice the only paper bag she owns for her daughter to carry her books in. Similarly, Borbély’s bucolic setting is barely discernable from medieval conditions: Borbély’s mother dreams of a home with a wooden rather than dirt floor, a twin bed with nightstands on either side, and—most importantly as a measure of living above mere needs—a dresser-and-mirror set:

“And when she finally had everything she desired,

there was no point anymore. On the ground, between

the left leg of the dresser and the door to the next room,

was a the largest pool of blood, congealed,

I scraped it off with a small shovel. I only conjectured that this was

my father’s blood. . .”

(This is as explicit as Borbély describes the in-home attack on his parents that killed his mother and significantly wounded his father, physically and psychologically.)

“Icarus in the Housing Project” describes that urban squalor that replaced the bucolic: “The thudding sound of kittens thrown out / of the tenth-story airshaft window produced only the / faintest of echoes.” “My buzzer rang after midnight, at that hour it was / the always cheerful gym teacher asking me / to let him in because his spouse and his small children were already asleep / and he could see through the light in my window I was up working. And so our / acquaintance in the urine-smelling lift began, then it continued next / to the garbage shut smelling of roach repellent / and disinfectant. I would have left, but he / held me back. Every one of his movements / begged me: Don’t leave me here.”

Translator Ottilie Mulzet’s afterword clarifies and situates the personal and historical background to Borbély’s works, in addition to conjuring lucid renderings of his poems.

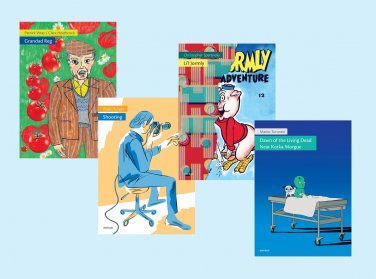

mini kuš! Series (#103-106)

mini kuš! Series (#103-106)

Grafiskie stasti

Here is the newest installment of mini-comics published in Latvia but representing cartoonists from a range of nations, styles, and techniques—qualities that make the series consistently satisfying. Each artist must work within the same physical parameters—24 pages, roughly 3”x5”, full color—but the rest is up to them. These comics can be hard to track down in the U.S., but they are easy to order from and the postage is included in the price. (U.S. distributors of the mini kuš series will charge the same price as the kuš site, plus tax and shipping.)

#103: Grandad Reg, by Patrick Wray and Clara Heathcock, occurs in the early days of the covid breakout, to which Grandad Reg succumbed. Depicted are a few presumably representative scenes that made him so beloved, such as greeting his grandkids after school every Wednesday with ice cream treats.

#104: Li’l Jormly, by Christopher Sperandio, is an exercise in absurdity via collage skills that allow Sperandio to seamlessly manipulate words and images from old comic books (1960s era?) so that, for instance, the eponymous character, Li’l Jormly, is a composite of a pig’s body and a chicken’s feet, with a single eye, a single tentacle (the other is a hand), and a toddler’s penis and scrotum. The comic includes word games and puzzles which are part of Li’l Jormly’s adventures (akin to running a gauntlet inside a meat grinder). Very nice.

#105: Shooting, by Pedro Burgos, is about a fashion photographer being photographed by the teenaged daughter of the make-up artist who accompanies the photographer’s fashion shoot.

Apparently, the photographer does not like being photographed and resents being on the other end of told what to do. The story is meh, but I liked the spare, suggestive lines and minimal color palette.

#106: Dawn of the Living Dead Near Kotka Morgue, by Marko Turunen, is also pandemic related. In this brief tale, the (unmasked) hero is approached by coughing strangers for directions to a building that turns out to be a covid testing station. Not sure why the hero is so miffed at being coughed on when he does nothing to protect himself.

Not Made by Slaves: Ethical Capitalism in the Age of Abolition

Not Made by Slaves: Ethical Capitalism in the Age of Abolition

Bronwen Everill

Harvard University Press

In the late 1700s, some businessmen decided to apply Abolitionist principles to international trade. These tradesmen from Britain and the Americas were also Quakers, and thus in touch with and supported by networks of shop owners and consumers in their home countries. They came upon the then-novel idea of making consumers aware that purchasing choices had ethical consequences: Thus, to buy slave-produced goods was to perpetuate slavery. In addition to the moral crime of slavery, they added, the production of, say, sugar and cotton was less efficient and more expensive in slave economies than in wage-compensated economies. That assertion, however, had no clear proof.

Bronwen Everill’s study of Abolitionist capitalism as it related to impeding and ending the sale and trade of slave-produced goods goes a good way to show why and how this ethical goal was so difficult to achieve. For starters is the fact that, in appeals to consumer conscience, any shop owner or wholesaler could claim to have free-produced cotton on hand. Since no way to distinguish the cottons existed based on who picked them, the market was vulnerable to fraud and thus the loss of consumer confidence in what they were economically supporting.

On the African side of trade, the Abolitionists encouraged agricultural and manufacturing exchanges among the continents rather than trade in human bodies, and Everill studies the written and oral records from the times for the Africans’ points of view. Overall, African traders had little problem coming up with items for trade that eventually more than made up for the wealth lost from exchanging bodies for goods.

A trail Everill does not follow but which she clearly indicates was intrinsically woven into the slave trade were the guns and liquor also favored by African buyers. As in the Americas, the introduction of guns into Africa disrupted long-standing local power arrangements, with the addition in Africa of some local leaders starting wars to find new bodies to enslave.

Everill finds her tradesmen stalking a moving target: Is wage slavery much different from non-wage slavery? What good is freedom without the ability to own property? These and other questions asked by merchants and their fellow Quaker congregants also revealed their applications to other scenarios not listed as slavery. As a result, and as slavery was eliminated in the Americas, questions about and battles over wage slavery among the general white population began in the late 19th-century.

Tariffs, government assistance, international trade agreements, and consumer awareness of the ethics behind their purchasing choices are still issues being dealt with in designing fair arrangements between producers, middlemen, and consumers. Everill shows what was tried, what worked, what didn’t, and why. It’s the sort of history that’s not even past.

Afternoon at McBurger’s

Afternoon at McBurger’s

Ana Galvañ (Jamie Richards, trans.)

Fantagraphics

Three 11-year-old girls visit the local McBurger’s to enter a contest aimed especially at 11-year-olds. Not everyone will win, of course, but those who do are sent 5 minutes in the future to one scenario of three of their choice. (One of those choices explains the book’s introductory scene.) Before that, though, we get to meet the girls, see their friendship, and glimpse fragments of what makes up their inner lives.

As with an earlier title by Galvañ published by Fantagraphics, Press Enter to Continue, the theme is based on future technology, although Afternoon lacks the earlier book’s Philip K. Dick-like paranoia. I like the simplicity of both Galvañ’s palette of pastel Risograph-quality colors and her line—thin, continuous, precise (and used sparingly), akin to work by C.F., Oliver Schrauwen, and Dash Shaw, with nostril shading via Lilli Carré. Jamie Richards’s translation from the Spanish is in clear, idiomatic English.

Winnie-the-Pooh

Winnie-the-Pooh

By A. A. Milne, illustrations by Ernest Shepard

Everyman’s Library

Now joining the Children’s Classics line of Everyman’s Library is A. A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh. Shepard’s illustrations were originally (1926) black and white, but in the 1970s he added watercolors, and those are reproduced here. Somehow the Pooh books eluded my childhood and my daughter’s, although she did watch (repeated) the Disney versions from the 1960s, which very often just lifted verbatim the book’s dialogue. Smart move.

The book’s humor is understated, sly, and absurd: a perfect introduction for children to irony. The humor often comes from Pooh’s use of logic to achieve rational ends, since his assumptions are all wrong—as are those of the other characters, save Christopher Robin, the young boy whose toys are Pooh, Piglet, Eeyore, Rabbit, Kanga, Roo, and Owl. And each toy is imbued with a specific neurosis: Eeyore is a depressive, passive-aggressive type seeking attention because lacking social graces; Rabbit is a compulsive organizer and list-maker who isn’t necessarily efficient; Owl a pretentious autodidact; and so forth.

While the first few stories involve just playing pretend, Milne seems to have thought, as the book went along, that the stakes needed to be higher than stealing honey from bees. So, by the time we first meet Kanga and Roo, the episode is devoted to fraud and kidnapping, escalating to the point at which a character’s life it at stake: a search for the North Pole and the rescue of Piglet during a flood. But these chapters exemplify the teamwork among the characters, showing their mutual care for each other and willingness to turn to each other for solutions. (The big problems are taken straight to Christopher Robin.)

Even though the stories’ events all take place outside in the Hundred Acre Wood, little narrative description is given over the local biota. The stories’ directions and outcomes are largely led by the personalities of Pooh & Co. rather than their interaction with nature, the flood tale being an exception.

Thus, the book deals with important skills such as negotiating personalities, working together, maintaining friendships in the face of personal differences, asking questions of authority (i.e., Christopher Robin) when help is needed, and treating each other fairly. What’s not to like?

[I arrogantly recommend…by Tom Bowden is a monthly column of small press and books-in-translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired pavement inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Reviewed books can be purchased direct from Book Beat by stopping by, emailing bookbeatorders@gmail.com or calling us at: (248)-968-1190. Some reviews are linked directly to the publisher when unavailable. Title links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page for out-of-town readers and mail-orders. Book Beat is credited with 30% of the sale from Bookshop.org and 10% of the sale is shared with indie bookstores nationwide. Thank you for your support! Subscribe to our newsletter for more updates. Read past small press reviews at: I arrogantly recommend… by Tom Bowden.]

I know Cary’s friend Steven is not short. He was sitting on a stool and he had book bags. Give him up Now.