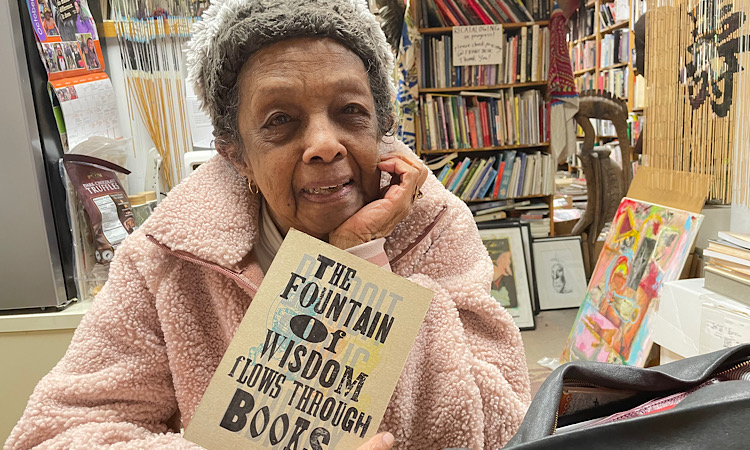

Shirley Tinsley is 98 years young. Shirley is a retired English teacher from Northwestern High School of Detroit and a member of our reading group. For most of us at Book Beat, Shirley is an inspiration. She is a devoted reader and generous soul who has spent her life loving books and we wanted to share some of her life wisdom and experience. On a cold February afternoon she came to the bookstore so we could record her thoughts and history. This interview was supplemented by some her own notes. Special thank you to her daughter Kim who helped arrange the interview.

Shirley Tinsley is 98 years young. Shirley is a retired English teacher from Northwestern High School of Detroit and a member of our reading group. For most of us at Book Beat, Shirley is an inspiration. She is a devoted reader and generous soul who has spent her life loving books and we wanted to share some of her life wisdom and experience. On a cold February afternoon she came to the bookstore so we could record her thoughts and history. This interview was supplemented by some her own notes. Special thank you to her daughter Kim who helped arrange the interview.

Growing Up in New Castle

I was born in New Castle, Pennsylvania in 1927, an industrial city about 50 miles from Pittsburgh. My father came from a family of ten boys and two girls. He had a couple years of college—there were black colleges in the south then and he grew up near Charlotte, North Carolina in a small town called Gastonia. The school there was the Lincoln Academy right outside of Kings Mountain. He settled in New Castle because there was a big tin mill there where he was employed.

I lived in a multi-generational household. It was my grandparent’s house. My grandfather was a good chef and he worked at the country club and hotels. They had always lived in Pennsylvania and my grandmother was active in the church. I was about nine years old when my grandfather was killed by a young 17 year old drunk driver—who ran into the back of his car.

During the depression my father worked on a farm and we always had food—we never thought we were poor. He also hunted game and would sometimes bring home a deer—but I didn’t want any of that meat.

In my hometown there was a Scottish woman who taught my mother and me English literature. I absolutely love Engish literature and I loved her too.

We went to the library usually more than once a week since we could check out only four at a time. Our voracious reading habits dictated that four books a week were not enough. In addition we read newspapers: The New Castle News and the Pittsburgh Post Gazette. On Sundays we always got the New York Times and occasionally the Cleveland Plain Dealer. And we read the weeklies from the Black Press; The Pittsburgh Currier, and The Review from Youngstown, Ohio.

Our grandmother was very politically active locally and we’d attend meetings, rallies and events to raise money for groups working to influence congress to pass anti-lynching and anti-Jim Crow laws.

I’ll never forget it was Halloween and our neighbor came over and scarred the bejesus out of me. And it was on that night that Orson Welles broadcasted his War of the Worlds. We were on the patio drinking cider with donuts just before going to bed. Our neighbor was all excited—and my father said, “no,no,no—that’s just a play on the radio.” And we heard her excitement but I couldn’t eat my donut or drink the cider.

I remember the Hindenburg too. The radio was sitting there, apiece of furniture and everybody listened to the news; the RCA Victor radio. And there was a chair right beside it, my grandfather’s chair and we used to cuddle on his lap. We had to listen because we had to be quiet. We listened to Amos and Andy. We listened to Jane Ace. Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons. In the thirties it was all about radio. It was after dinner and the shows were just 15 minutes long.

My grandmother got me into a good high school but I was the only black student—it was a feeder for Harvard and Princeton—and I had to live away from home and walk every day to classes. So, I’d see this little girl everyday on my way to class—she lived up the hill a little and she’d sit on her bicycle and say, “nigger nigger, hi nigger.” And it really hurt me but I didn’t do anything. So one day I thought this is dumb—so I said, “What’s your name?” She told me her name. I said, “Well my name is Shirley. Why don’t you say hi Shirley when you see me?” She just didn’t know. I missed home so much, I saved a quarter until Thursday and then I’d call my mother and say, “You better come and pick me up or I’m going to start walking home!” And she’d say, “Shirley, just hold on, you’re going to be a winner.”

My high school years were the war years—the rationing of certain foods and petroleum. There were few males in my class because either they were drafted of raised their age to join the armed forces. Stars were displayed in neighborhood windows to indicate the service or death of a family member. The air-raid drills, the civil patrols, blackouts and curfews.

The four years after the war were college years for me.

Working in Germany

Around 1950, after I graduated college, I took a job at the YMCA. I met a girl from Youngstown and she told me about the overseas service centers –she was stationed in Munich. And she said to apply for it and I got it. We went over in a ship and were stationed in Frankfurt in northern Germany—a little town called Herbst.

There were a lot of facilities—`we had instruments, a piano, crafts, and a library. This was still during reconstruction—the area was opened in 1945 and the army was still segregated. I was with the 1279 corps of engineers that were from Inkster, Michigan—but little did I know then that I’d wind up in Michigan. We all lived in a lovely house. I’m sure it was confiscated. I remember the Harlem Globetrotters would come out on tour—and Bob Hope—all these great entertainers came all the time.

I remember one incident with the Globetrotters when they were staying at a guest house and these soldiers came in and they needed some beer—and then a tussle started with these white soldiers. What concerned me—and I thought about it afterwards is what we are reinforcing is everything we left behind in America.

I remember this one station break song in the United States from the 40s and 50s went like this: “I’m proud to be me but I also see you’re just as proud to be you. We may look at things a bit differently but lots of good people do. It’s just human nature so why should I hate you for being as human as I? We’ll get as we give if we live and let live, so let’s all get along if we try. I’m proud to be me but I also see you’re just as proud to be you, It’s true, you’re just as proud to be you.” Here’s another station break jingle: “What makes a good American? What do you have to be? Are you a good American? Let’s take a look and see. Like democracy….” I can’t remember all the words but the last thing was “do you practice what you preach?” We were hearing all that everyday—these were positive jingles.

They played these positive jingles instead of ads. At the time there wasn’t much television—these were all on the radio. They were putting out this positive propaganda thing but they weren’t really practicing it. That’s what the German’s were seeing. There’s a great Te-Nehisi Coates quotation from his last book, “Kindness is the only non-delusional response to everything good.”

One day Senator McCarthy and Roy Cohn came to the Army base. See, he was looking at and censoring the books in all the Army department and State libraries. My main base was 20 minutes from where I worked. The high command for Europe and Eisenhower was in Frankfurt- and he soon left to run for President.

McCarthy and Cohn came basically to purge and censor books and authors that they thought were communist leaning—and I wrote down some of the names of the authors they pulled out—Ernest Hemingway, Theodore Drieser, Dos Pasos, Mark Twain, John Steinbeck, Langston Hughes, Upton Sinclair, Lillian Hellmen, Dashiell Hammett, and others. These were all verboten –and taken away.

Roy Cohn’s paramour was David Schein and they traveled together. And I remember something happened in Munich and they were asked to leave. It was some kind of sexual thing, but I can’t remember what—a scandal of some kind.

Many librarians were ready to quit their jobs or forced to sign affidavits about never being a communist. Where I worked we didn’t have a library but rather a “reading room” where many newspapers and paperback books were available. However on the bases there were libraries because the service men’s wives and families were allowed to come to Germany.

I saw the autobahn—the system of highways that connected everything in Germany—and the idea that Eisenhower sponsored for the interstates we now have. I saw many brown babies in the orphanages –and many of the soldiers adopted them and brought them home. But all of this made me think of the examples from our country—it seemed we were affirming some of Germany’s 1930s beliefs.

After I came back I worked in Missouri and that’s where I met my husband who was from Detroit. He was in the service.

Living and Teaching in Detroit

I used to save twenty dollars to buy groceries every two weeks—and out of that I’d save about $1.50 to bring home a book for each daughter. Isn’t that something? I’m not perfect—I’m only human but you just try to do things so your children will know that’s the right thing to do.

The best A&P in town used to be on Puritan and Six mile road. That’s where the good meat was supposed to be. One day I was at the meat counter and I looked down and there was $20 on the floor and I thought, you know someone might come in here like I do—and all they have is $20 —and so I turned it in. Do you think that person ever got it back? Probably not, but I try and do the right thing.

We lived two short blocks down from the University of Detroit. I started teaching when my youngest daughter was three years old. So that would be 1968. It was right after the riots. I can remember, the birds weren’t even singing. And tanks rolled right across our yard. The National Guard going up and down our streets. The children weren’t out. It was still. My husband lost all his shirts. They were at the cleaners on Puritan that burned down.

Both of my kids started school early because they could read. They missed kindergarten and first grade—they were ahead if it. And I cannot tell you how they learned. I just read a lot to them and they picked it up. They must of just followed what I was doing.

Let me tell you what my husband did. One day I found my daughter Kelly and her girlfriend looking through my husband’s Playboy Magazine. I said, “Kelly, that’s your Dad’s magazine, you have to ask him permission if you can look at it.” I told my husband later and he said she asked permission. So he pulled down the magazine and said, “if you can read this, you can look at it.” Did she read it? She didn’t understand a word but she could unlock it. I said to him, “you don’t ever do that with a kid.” They know more than you think they know –that’s why I liked to have my students read Go Tell it on the Mountain, they know more than you give them credit for. They also use and pick up what they can handle. I don’t have to worry about talking about it with them, if they want to discuss something that’s fine, I’ll discuss anything with them.

One thing about the sixties was the Black Power Movement—and they would come into our classrooms and try to drum up business.. trying to get kids to come out of class, to stop the schools. And I’d say-let them come in. I’d let them make their spiel. I didn’t have one kid leave my class. I don’t think they were Black Panthers. They were just rebels—wanting things done right away. Ken Cockrel was part of it—he lived just across the street from the school. Him and his wife Sheila lived on Parkside.

Teaching James Baldwin

When I started to teach in Detroit I used Baldwin’s Go Tell It On the Mountain. I found out that if you use a male protagonist it works. For girls they don’t care, but boys do. They do. I wanted them to read Baldwin—but I thought the essays were a little too much. But I thought here you have a boy as the lead charcter—and it was a bestseller in 1952. We read it and you find out kids pick from the stories what they can handle—and you don’t have to worry about the sexual stuff. But at 14 or 15, you’re going through the same thing— Baldwin’s just such a genius at laying it out. The underlacing of metaphor and symbolism is there but you need to read it several times, at different stages in your life, because you see more in it. I used it at Northwestern high school for tenth grade students in the 70s and 80s. I didn’t have any complaint from parents and tried to get them to relate to it.

We had 35 students in my class and I divided the class into groups of seven to work on a film—we used video then –to take the book’s ideas and relate it to themselves. One group wrote the story, another scouted locations, one group selected music, and another worked on technical problems and permissions—it led to some interesting discussions about store front churches, the hospitals, jobs, and all these issues.

The church is really strong in Detroit as it was for Baldwin, but what I thought was different was home ownership, the Islamic brotherhood, Malcolm X and the influence of music. I’d always see four brothers on the street corner singing. I wanted students to look at their lives and contrast that to what Baldwin observed.

I went to Princeton once and sat in on a class by Eddie Glaude but he really got on my nerves. Him and Cornel West were in the same department and taught this class together. Eddie Glaude just makes me sick when he talks about Jimmy. Why can’t he call him Mr. Baldwin? Eddie Glaude didn’t vote in the last election. That really upset me and I’m holding a grudge.

The misogyny in Go Tell It on the Mountain runs deep—but it really showed the women were the ones taking responsibility for their actions but the men did not. I thought about that a lot. And there’s the expectations of your family—that’s also in there. If your family is dealing drugs—what do you do? All these things are there in the book and impact your life; religion, family, the environment and the injustices you feel. If you ever find the book The Long Dream by Richard Wright, read it. Its an achievement for Wright—and another coming of age story—and now if I had the chance I would teach them in tandem.

On Reading The Oppermanns

So many thoughts were whirling in my head as I was reading The Oppermanns by Leon Fuechtwanger, it made me want to be in the classroom again teaching 12th grade students. The book is so rich in possibilities for students. There is so much for creative assignments and discussions. The thought makes me think of un retirement! Secondly, I thought of my life and time in comparison to the life and times of the characters. “Declared aims run contrary to actions,” said Ta-Nehisi Coates.

I kept thinking about what I was doing in 1932 and 1933—while that was happening. It was the New Deal here and the country was coming out of the depression. Social Security had just started. I was too young to understand the atrocities the author describes in the book—but I understand it now. I see it. I don’t know how to say this, but when I grew up there were standards. Your parents expected things from you. And they tried to live in way to set an example for their children. I don’t see that at all now or very little of it.

I never imagined that I would have a job in the 1950s in the country that not only produced the author of The Oppermanns but also banned his writing for political purposes. Written in just nine months and published shortly after Hitler became chancellor in 1933–as Jewish property was being seized and Jews were stripped of German citizenship. It exposed the erasure of dissenting voices and perspective—the growing threat by Nazis to intellectual life and freedom—opening the real possibility of books being burned. This quote by Heine: “Those who burn books will eventually burn people.”

If I was teaching The Oppermanns in class now, it would be interesting to contrast it with the political climate today.