I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, ephemeral, small press, comics, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, “This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.”

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If you notice titles unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at: i arrogantly recommend…

We Have Ceased to See the Purpose: Essential Speeches

We Have Ceased to See the Purpose: Essential Speeches

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

University of Notre Dame Press

We Have Ceased to See the Purpose collects ten speeches delivered by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn over the course of 25 years, ranging from his Nobel Prize acceptance (1972) to a cultural complaint to fellow Russians upon his return to Russia, after the fall of the Soviet Empire (1997).

For Solzhenitsyn—prisoner of conscience who lived through, worked in, and survived years in the Soviet Union’s gulag prison network—the similarities between contemporary Western and Eastern governments, communist and capitalist, are their unshakeable beliefs in materialism and humanism as the pinnacle of authority upon which a life devoted to pleasure for the sake of itself is rationalized. As belief in the Spiritual ceded its authority to the Material, beginning with the Renaissance, “a long era of humanistic individualism [began], the construction of a civilization based on the principle that man is the measure of all things, that man is above all.”

The spirit of Munich [Quisling’s capitulation to Hitler to maintain “peace in our time”] is a malady of the will of affluent people; it is the chronic condition of those who’ve abandoned themselves to the pursuit of prosperity at any price, who’ve succumbed to a belief in material well-being as the principal goal of life on earth. Such people…choose passivity and retreat, just so long as their accustomed life might be made to last a little longer, just so long as the transition to hardship might be put off for another day…

Solzhenitsyn insisted on telling his Western audience that they were on their way to making the same mistakes, committing the same crimes, as were occurring within the broader Soviet sphere of influence. Of course, this message to the West was ignored and went unappreciated. Western anti-communists assumed that Solzhenitsyn, once freed from Soviet tyranny, would serve as product spokesman for capitalist materialism. His failure to do so made him again ignorable by Western intellectuals less keen on promoting human rights than their own self-serving impulses. Here’s some of what they didn’t want to hear:

If, as claimed by humanism, man were born only to be happy, he would not also be born to die. Since his body is doomed to death, his task on earth must evidently be more spiritual: not to gorge on everyday life, not to search for the best ways of obtaining material goods and then to consume them eagerly, but to bear perpetual, earnest duty, so that one’s entire life journey may become, above all, an experience of moral ascent—to leave life a better human being than one started it.

Material laws alone neither explain our life nor give it direction. The laws of physics and physiology will never reveal the indubitable manner in which the Creator constantly, day in and day out, participates in the life of each one of us, unfailingly fortifying us with the energy of existence.

But lives dedicated—and limited—to unconstrained pursuits of happiness (defined as endless consumerism) morally deform the persons who adopt material gain as their credo. The Trump White House (and those who elected him) exemplifies this attitude. With no one or thing to answer to for at the ultimate accounting of their life, Solzhenitsyn’s theology holds, there are no reins to hold back leaders from engaging in pure evil—which is what Soviet leaders were doing, had been doing, for decades, and which is what Solzhenitsyn was warning of nearly 50 years ago to the West about our “lifestyles.” As I’ve seen on my own visits to the authoritarian-ruled, hyper-capitalist China, affluence can buy a lot of complacency. I don’t think Solzhenitsyn wanted a return to theocracy, but at least a turn to rule as governed by a sense of decency owed fellow human beings. Among Solzhenitsyn’s first principles must be Matthew 25:40, “What you do unto the least of them…” Violating God’s creation is akin to violating God. Treating fellow humans decently is the same as treating God decently. That said, in my own admittedly feeble knowledge of world history, I can’t think of a single leader whose will to mass murder was stayed by a fear of punishment from God. Thinking that they would be rewarded by God, now those leaders I’ve heard of.

We Have Ceased to See the Purpose serves both to present forceful ideas relevant to today’s cultural catastrophe and help fill the remaining gaps in Solzhenitsyn’s works to be translated into English, thanks to The Center for Ethics and Culture Solzhenitsyn Series at Notre Dame University.

Tedward

Tedward

Josh Pettinger

Fantagraphics

The eponymous hero of Tedward is a hapless nebbish whose persistent attempts to attain a normcore life are thwarted just as persistently. The behavior is juvenile, but the action is adult, so buyer beware. Following the picaresque tradition of storytelling—a series of stand-alone incidents involving the hero but not necessarily along with a narrative arc of beginning, middle, and end and a changed hero—Tedward’s life is an unending sprawl of one damn thing after another…beginning with a job Tedward is gang pressed into performing before he escapes—that of hosing off semen from bodies of orgy participants, then moving on to collecting money from television collection boxes attached to the TVs of people who only watch it by the half-hour. More witness to corruption occurs. So, yes, Tedward’s adventures are both absurd and uncomfortably plausible. If you’re prone to viewing humanity with a gimlet eye, here’s the gin and lime juice to go with it.

Gallery

Gallery

Stephen Emmerson

Timglaset

Readers of Lawrence Weschler’s Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder (1995) will recall much of that slim book being devoted to David Hildebrand Wilson and Diana Drake Wilson’s Museum of Jurassic Technology, a building in Los Angeles with exhibits that are both funny and serve as commentary on theories of curation and display. One needn’t be in on the jokes to appreciate the absurdities they present (how many degreed museum curators can there be?) or to enjoy the exhibits themselves. Stephen Emmerson’s Gallery extend the Wilsons’ prank with 30 museum placards, two museum floorplans, and 25 context cards. Were Gallery a book rather than a box of cards, the contents could be read as a deadpan ode to conceptual art. But since these are cards—actual cards one might see displayed in a museum or that one might be tempted to append to a museum exhibit—they don’t act as placards, they are placards whose potential energies—as physicists might put it—are activated once the cards are exhibited. Two examples:

Hold On to This Page in the Dark / White A4 paper, black printer ink. / Dimensions: 29.7cm x 21.0cm. / 2002. / Performed in various spaces.

Portrait at Distance / This portrait of Alicia Evans was created using a graphite stick tied to a 15ft pole. Holding the far end of the pole with one hand the artist attempted make the best likeness of the sitter. The resulting abstract minimalist image won the Jerwood Drawing prize in 2012. / Graphite stick on acid free paper. / Dimensions: 190cm x 86cm. / 2011. / Courtesy of the Jerwood Foundation.

Floor plans for two museums include galleries with such names as Traumasurge, Immaterials, Marble Index, and Zero Hours Contract.

Context cards—“designed to be placed next to any object, scene, or event—and for that object, scene, or even to become a work of art”—allow persons of even the humblest of means to transform their abode into a hip destination of collected works by Emmerson: “Reclaimed living quarters (zones of incompetence) / 2011”; “Portable meditation console / 2014”; and so forth.

Better than placards reading merely “Untitled,” Gallery shows that aesthetics transcends materials and their matter-of-fact descriptions while leaving unanswered what about any juxtaposition of materials imbues them with artistic qualities. Readers dubious of the merits of such placards haven’t been to a museum lately.

Strange and Perfect Account from the Permafrost

Strange and Perfect Account from the Permafrost

Donald Niedekker/Jonathan Reeder

Sandorf Passage

A story told by the spirit of an unknown poet who was part of an expedition, in 1597, to find passage from northeast Russia to China. The poet didn’t get far on the expedition before taking ill and dying; he was buried on an uninhabited island among the archipelago between the Barents and Kara Seas. Because of global warming, things in the Arctic once buried by snow and ice are being revealed—or released, as in the case of methane gas once frozen in the taiga now evaporating into the atmosphere. Because the land has started warming, the poet’s frozen soul thaws enough to describe the history it has witnessed during the 400-plus years its body has been interred on this barren nothing, Novaya Zemlya.

When this poet first set off, 400 odd years ago, he was living in a golden age of exploration for Western Europeans, a time when a few years of risk at sea could return significant riches. Or not. The hubbub and optimism of early capitalism are captured in the narrator’s description of why the elements of his day were also the elements of his voyage’s failure:

Our expedition was a flop, exactly what you get when you roll together pigheadedness, absurdly speculative theories, a blatant denial of the polar landscape, and an unwillingness to learn from native people who have lived there for centuries. It did not even occur to us to consult the Samoyeds as to clothing suitable for these extreme conditions—we were already savoring the scent of the orange trees of China.

But after the narrator’s ship is iced in among a chain of small islands, motionless for months, the scent of those oranges can’t cover the fact that

We were more sick than hungry. Bleeding, shriveled gums. Scurvy. Words I had not earmarked for my ode. Teeth loosened and, one day, fell out of your mouth or wound up stuck in a hunk of fox meat, like fate’s dice, a deposit on Charon’s fare.

Contrasting with the narrator’s description of his life and Dutch culture are those of Arctic nature, the cycles of which has witnessed for years, its beauty and indifference to life once in balance, now in turmoil because of the advances made in the name of progress that put in place, in the 16th century, the mechanisms behind today’s ecological emergency. Just as the narrator found out too late the mortal risk behind the charm of being ship’s poet, his message to us may have also arrived too late to learn from it.

East District

East District

Ash H.G.

2dcloud

A brief graphic novel that reads like being dropped in a different world for 30 minutes and trying to piece together what is going on from the moments witnessed. The settings are stark, mostly desolate exurbia, combining woods, grassy plains, abandoned industrial parks, and tidy neighborhoods. The characters seem to be in their late teens (one talks about getting ready for college), and their interests alternate from collecting baseball cards, to partying and flirtation, to killing what may be zombies. East District develops the unsettling feelings it creates from the alternating tensions between normal teenage activities and unexpected bouts of fatal violence. Going to dances doesn’t seem to require an explanation for readers, but the visions one of the characters has and the deaths that accompanying them do but never are given. It’s a world in which people try to go casually about their business and push aside dwelling on life’s unpredictable horrors but can’t. The sticks carried by the protagonists to protect themselves from and to use against the zombies aren’t long enough for to leverage their way out.

Desire and Fate

Desire and Fate

David Rieff

Eris

With Trump in the White House, the so-called woke movement is DOA as we enter a new era. By the time Trump was elected, woke-ism had already run its course: When members of the Left start complaining about a movement started by others on the Left (you could replace “Left” with “Right”), the movement was dying, anyway. Trump just sped up its demise. As a movement predicated on empathy—taking seriously the living conditions of some of humanity’s most-despised members—being “woke” indicated a sensitivity towards physical and psychological differences, and an antipathy toward the social conditions giving rise to such hostilities. It was the enforcement wing of the woke-ism movement that engendered its angriest reactions.

As a document of the time and the movement’s goals, the essays comprising Desire and Fate present an impressive headcount of offenses against taste and common sense, a catalog of offending movement leaders and their often-asinine assertions based on a self-hatred best left to those leaders and their therapists rather than writing endless corporate and governmental proscriptions, regulations, and laws designed to punish any and all persons possessed of contrary notions. (I’m thinking here of the whites who claim that, merely because they are white, they are inherently racist—and so is everybody else who is racist, and that hiring and retention practices, for instance, should reflect that. That these alleged genetic imperfections are heritable only by other white people makes these claims as racist as those they are intended to fight.) Among the tamer of the nonsensical woke actions are adding trigger warnings to copies of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea read by Scottish islanders for its graphic depictions of fishing.

Trigger warnings, identity politics, and hostility toward free speech and the open exchange of ideas all form part of what Rieff identifies as “the radical subjectivity that is at the core of identity politics”:

For, while it is possible to agree on, say, how much food a person needs to thrive, it is impossible for anyone—save for the person or the group expressing the need—to say how much recognition, or affirmation, or sense of psychic security they need, or, as they would say, are entitled to. But it should be obvious that it is impossible to correlate the contemporary expansion of needs with a similar expansion in the number of rights.

A great proponent of woke-ism is capitalism, which treats all matters of ethics, philosophy, political science, and so forth as forms of “lifestyle” to market. My first strong hint of this came long before the Woke movement with the release of Spike Lee’s film about Malcolm X, which, among the film’s marketing tie-ins (of course!) were hats with a letter X above the front brim. Licensing the use of a letter of the alphabet! For a film about civil rights! Gil-Scot Heron was right—the revolution will not be televised: it will be franchised to the highest bidder as a form of (designer) virtue signaling.

However convincing Rieff’s arguments are about sympathies gone terribly awry, they could be shored up, focused, and made more powerful were they organized by topic. Desire and Fate has no organizing principle. The essays comprising the book don’t include dates or notes on where they were originally published (if published before). As a result, the overall effect is of authorial flailing against an amorphous force called Woke. RIP.

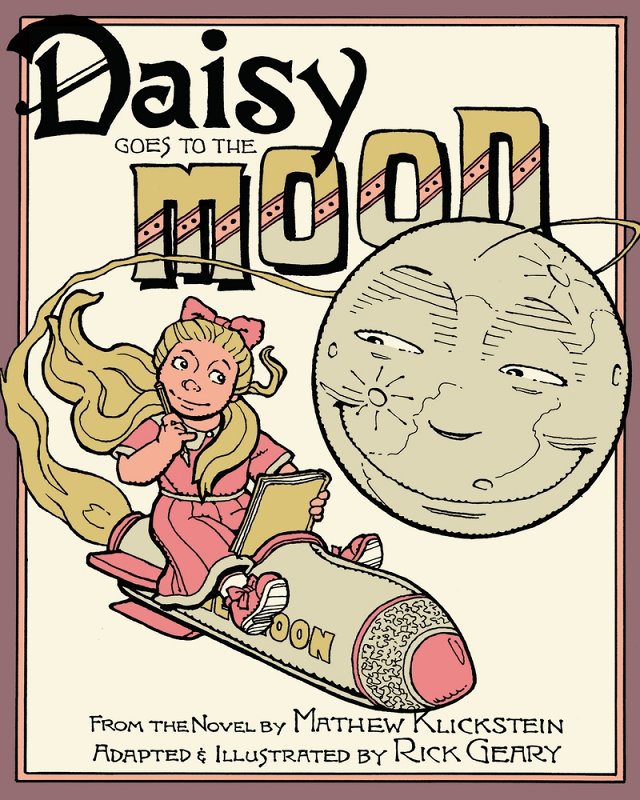

Daisy Goes to the Moon

Daisy Goes to the Moon

Mathew Klickstein and Rick Geary

Fantagraphics

“You didn’t think that going to the moon would be all bouncy shoes and marshmallow pies did you?”

Daisy Goes to the Moon is a not-just-for-children’s book with a complicated past: In the late 19th-century, a Victorian girl, from ages 4 to 14, wrote a series of adventures about herself for her family. Thirty years later, Daisy Ashford—the author herself—found the stories in a trunk, was amused by their sophisticated vocabulary and rich trove of deeds, which somehow lead to the stories together being promoted by J. M. Barrie, author of Peter Pan, and forming a best-selling book. Decades later, author Mathew Klickstein discovered the stories, was charmed by them, kept a notebook of Daisy’s Victorian-era vocabulary and non-standard spellings, then channeled Daisy’s spirit into a new set of adventures, which were published by a now-defunct indie press out of Portland and happened upon by veteran cartoonist Rick Geary, who agreed to adapt Klickstein’s adaptation of Daisy into a graphic novella.

And here we are. With a penchant for figures squat and round or thin and spikey, Geary’s style reminds me of Rudolph Dirks’s The Katzenjammer Kids from early 20th newspaper comics pages—and thus a good visual match for the narrative mood.

The story begins on a sunny morning before breakfast while Daisy sits below a tree, writing, drawing, and imagining. Soon, a rocket descends from the sky, and a thin, lanky man named Zogobythm introduces himself to Daisy and invites her to accompany him to the moon. More concerned that she hasn’t eaten yet than she is about notifying her caretakers of her absence, Daisy reluctantly agrees to accompany Mr. Z to the moon where, before she can satisfy her appetite, she goes shopping for pink shoes. . . Daisy is cloned, and her clone disappears with a man from the future (who carries a TV) named B. Blahdel. . . A disastrous fight on board a rocket is saved from catastrophe by a “servette” (Daisy’s name for what we could call a robot). . . Daisy and Messrs Z and B find themselves captured and bound by stinky Venusians. Will they be tortured and interrogated? Daisy instead asks the men, “Have we any choklate?” Etc.

Klickstein’s conceit of writing from the perspective of a child—and a child’s tendency to put its own concerns about those of all others’—including non-sequitur turns of events, straight-faced absurdity, and unself-conscious presentation—coupled with Geary’s illustrations and Alice-in-Wonderland-like characterizations makes for an excellent match and a book that an adult might enjoy reading alone (stoned) or to a kid (sober), for whom anything unlikely is still part of unquestioned imaginative possibility.