I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, ephemeral, small press, comics, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, “This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.”

I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, ephemeral, small press, comics, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, “This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.”

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If you notice titles unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at: i arrogantly recommend…

BardCode

BardCode

Gregory Betts

Penteract Press

In 2001, Steve Vitiello, composer of electronic music, released an album called Bright and Dusty Things, which consisted of musical translations of light reflecting from buildings, billboards, and other stationary objects. Using a photocell, light vibrations were converted into sound vibrations (which underwent further signal processing). What does a building sound like on a cloudy day? There’s a way to find out.

In BardCode, Gregory Betts does something similar with Shakespeare’s sonnets: He takes the transcription into Roman letters of spoken sound and assigns the sound of each syllable a color. End rhymes, of course, are immediately easy to spot. But the matching interior colors—are those internal rhymes? Clusters of consonants? Can the poems’ semantic or emotional content be inferred from the colors? If a poem is sonically harmonious, will the colors harmonize, too, in some way—that is, will certain ratios of color combinations occur that give the overall image a balance? Are colors and sounds separate from each other, or can the colors assigned syllables reinforce or somehow support the semantic content of each word by itself and taken in totality with each poem’s theme? The poet Philip Terry, in his preface to BardCode, calls Betts’s work data poetry. And, yes, BardCode does translate Shakespeare’s poems into units of data, but that description is far too reductionist and dismissive of the rich possibilities, aesthetic and prosaic, of discovering or re-discovering the sheer fecundity of Shakespeare’s sense of word-and-sound, which has always been rife with visual metaphor and analogy, to which a new way of seeing has been added. Highly recommended. [https://apothecaryarchive.com/bardcode-projects]

With Their Hearts in Their Boots

With Their Hearts in Their Boots

Jean-Pierre Martinet / Alex Andriesse

Wakefield Press

[Henri] Calet said it. Fucking life.

Because this isn’t the way it should have been.

—Martinent’s appreciation of Henri Calet, “At the Back of the Courtyard on the Right.”

A once-promising actor, Georges Maman, now a down-on-his-heels never-was in his early 40s, unable even to keep an erection for a porn film that would buy a week’s worth of groceries (or booze, depending on priorities), wanders into a bar (priorities!) to lick the past two decades’ worth of wounds. There, he is chanced upon by a man named Dagonard, an assistant TV-series director of the same age, employed but just, garrulous but unlikeable, a man who likes to treat others to a few drinks and who Maman can depend upon for a few hundred francs he will never repay. And of course, there is a woman—Marie—who broke Georges’s heart once upon a time, and about whom Dagonard is repeatedly tactless enough—aggressively so—to not let Maman forget, even though her appearance on countless magazine covers would suffice to salt Maman’s sore spots.

A pair of bitter men without women, directionless drunks who, though still in early middle age, are well into their years of “what ifs.” Marie Beretta—like the gun: the story starts and ends with her.

The novella With Their Hearts in Their Boots is accompanied by Martinet’s essay on the French noir novelist Henry Calet, “At the Back of the Courtyard on the Right,” which reads like a heterosexual version of William Burroughs describing life among the impoverished and seedy in New York, Mexico, and Tangiers, retailed in prose more infused with drunken delirium than hallucinogenic cut-ups, the effect—a life deliberately at odds with itself—remains the same. A pair of short jabs to the jaw, deftly aimed.

The High Life

The High Life

Jean-Pierre Martinet / Henry Vale

Wakefield Press

In the ironically titled The High Life, Adolphe Marlaud works for a “funerary shop” in Paris where he tends to the needs of grieving families, families he disdains, so that his very desire to help is itself an act of hostility. (“Oh, I insist!” one can imagine him saying.) Marlaud is one of Jim Thompson’s Underground Men via Rainer Werner Fassbinder. He’s four-and-a-half feet tall, in lifts, and weighs 85 pounds. During World War II, his father divorced his mother, who was then forced to take back her family name—Jacob—and thus had no protection from the Nazis who executed her after Marlaud’s father turned her in—“Just to teach her some manners”—for having had an affair. During his off hours, Marlaud either tends his father’s gravesite (which is near where he lives), reads, or watches movies. (Given the noir tone of the story, I’m sure that’s “Marlaud” as in “Philip Marlowe.”) A neighbor, Madame C., takes a liking to Marlaud and intimidates him into have sex with her. At six-foot six and 200 pounds, her coupling with a man two feet shorter is difficult for us to imagine, but her demand for anal sex proves too much for the chronically asthmatic Marlaud to imagine, and he flees her apartment, going into hiding from for two weeks. Where does somebody who has vowed to “live as little as possible so as to suffer as little as possible” find the strength to carry on in such an overwhelming world? American readers won’t be surprised to find Marlaud ultimately finds solace in owning a gun.

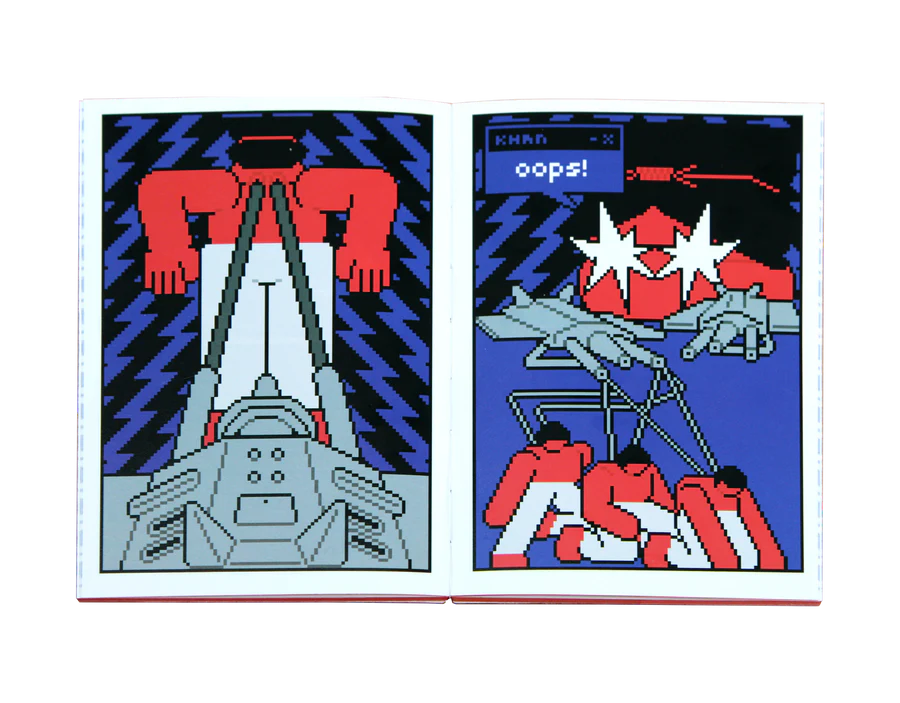

Ritual Machine

Ritual Machine

Toyoya Li

Paradise Systems

The first graphic novel from Beijing cartoonist Toyoya Li told and drawn as an ‘80s-era, 8-bit pixelation computer game, the premise of which is to “Escape the matrix. Find the wizard’s room. Free from the chains of the world.” Keeping with in the minimalist constraints of early gaming and its visual representations, the game has only three characters—Khan (“adventure-loving horse rider”), Tinan (“a rebellious hacker and Khan’s friend”), and Virtual Wizard (“with mystical powers, a seer”)—and works within a color palette consisting largely of black, red, blue, and white, with the occasional grey and yellow. What passes for a storyline is the usual computer-game mayhem, expressed with surprising visual range and complexity, given the limitations of the medium imitated. Completing the book’s presentation as an art object, too, the covers are comprised of laminated 3D gifs.

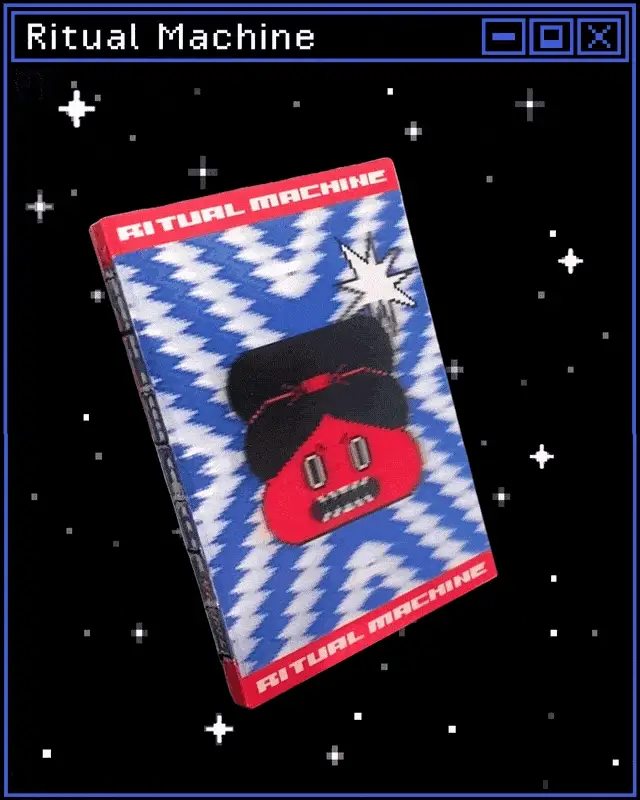

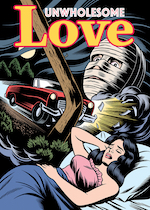

Unwholesome Love

Unwholesome Love

Charles Burns

Partner & Sons

2024 was quite a year for fans of Charles Burns’ comics: Final Cut (collecting the three volumes originally released in French as Dédales), Kommix, Sweet Dreams, plus the stand-alone comic book Unwholesome Love and the first volume of the new The Art of series. Unwholesome Love follows Burns’s current interest in American romance comics from the mid-1950s involving torn lovers, disfiguring automobile crashes, and barely sublimated eroticism paired with naïve ideals about love and romance. Three fragmented tales make up Unwholesome Love, a comic book that at first feels like an anthology of love stories but over time become apparent as one story with crucial elements missing, perhaps the result of memory loss inflicted by one of the book’s car crashes. Because this is Burns, we’re going to be given a story that, in addition to its absurdities, needs to be pieced together, more-or-less, while also assuring us with its circular narrative that we have all we need. The illustrations bear Burns’s hallmark style: high-contrast black and white images drawn with simplified but realistic and dead-pan earnestness, all in service of unspooling a tale in which everyday normality confront the world’s Lynchian irrational powers.

The Art of

The Art of

Banzaï Editions

Banzaï Editions is a French publisher of comic books and graphic novels for adults whose catalog includes works by American, French, and Japanese artists. Now going into its thirty-fourth year, Banzaï has launched a new monthly series called The Art of, each issue of which includes 32 pages of full-size images by a single artist (in color and black and white, depending on its original appearance), a poster by the artist, and a booklet in French and English providing a brief bio, bibliography, and essay about the artist, as well as an index of the images shown in The Art of issue and their sources.

The inaugural issue provides an overview of Charles Burns’s career, including his contributions to RAW, album covers, El Borbah, Black Hole, and the New Yorker (his take on Eustace Tilly was a lost opportunity for the Condé-Nast empire). While many of the images have originally appeared elsewhere, The Art of edition also includes reproductions of original comic book pages. Upcoming issues will focus on the art of Moebius, Moon Patrol, Cristina Daura, Derf Backderf, Ryan Heshka, and Shintaro Kago. I don’t know how easily available this series will be in the U.S., so I strongly urge fans of the medium to subscribe. Subscriptions are available in six- and twelve-month spans.

Mafalda

Mafalda

Quino / Frank Wynne

Elsewhere Editions

With a bowl cut and hair ribbon like Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy and a persnickety attitude like Lucy Van Pelt’s, Quino’s Mafalda is a children’s cartoon character granted the ability to worry about things that concern adults: war and peace, political and educational divisions, ecology, women’s rights, the social costs of progress, and so forth. Pretty heady stuff for a six-year-old but no more cerebral than the issues faced and discussed by Charles Schulz’s Peanuts cast or, for that matter, A. A. Milne’s Pooh and Friends.

Argentine cartoonist Quino’s Mafalda is joined by Felipe, Susanita, Manolito, and Miguelito—other kids her age with their own eccentricities. Made up of three- and four-panel strips that ran from 1964 to 1973 and were translated into 26 languages, Mafalda appeared in magazines and newspapers from around the world and counted among its fans Umberto Eco, Julio Cortázar, and Gabriel García Márquez. Kids will enjoy Mafalda mixing up her tube of paint with her father’s tube of toothpaste and confusing her father’s looking up a word in a dictionary as a hapless reading of a large book, one paragraph at a time. Adults can find bitter solace in Manolito’s assurances that nuclear war is unlikely: “See, war is like a market…And both sides have to be savvy businessmen…That’s why the other guys aren’t going to drop bombs and blow up Papa’s grocery store…Papa says wolves don’t eat their own.” Although the concept of universalism has been sneered at for the past 40 years, evidence of its existence can be found in the pages of Mafalda.

The Philosopher

The Philosopher

Tom Jenks

Sublunary Editions

The doughnut is defined by its hole, and yet without the doughnut the hole has no meaning, explains the philosopher to the assistant in the supermarket café, which will close for refurbishment this evening, for the duration of the season.

—The Philosopher

The style, tone, and approach of Tom Jenks’s The Philosopher resembles a shorter version the late novels of David Markson or excerpts from Georg Christoph Lichtenberg’s The Waste Books.

Happiness consists in frequent repetition of pleasure, murmurs the philosopher, opening another packet of sea salt pistachios.

Its brevity, however, prevents the development of a narrative arc a la Markson in the former, and replaces in the latter, questions of scientific investigations with those of philosophical investigations into the quotidian. Both Markson and Lichtenberg are aphoristic in the manner of summing up a life.

With sadness, the philosopher discovers a stain on his copy of Edifying Discourses, caused either by overspill from his NutriBullet 600 Series High Speed Blender or leakage from a 1 kg jar of sauerkraut. In this instance, decides the philosopher, the particularities are not particularly relevant.

In terms of comedy history, The Philosopher’s act of making bathetic the Important Questions of philosophy remind me of early Woody Allen from his stand-up days and of Steve Wright. I’d like to see The Philosopher expanded, to see what the Philosopher makes of his neighbors in the neighborhood by the artificial lake, the sort of post-suburban questions about just getting by he might ask.