A Conversation with Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr., Citizen Printer

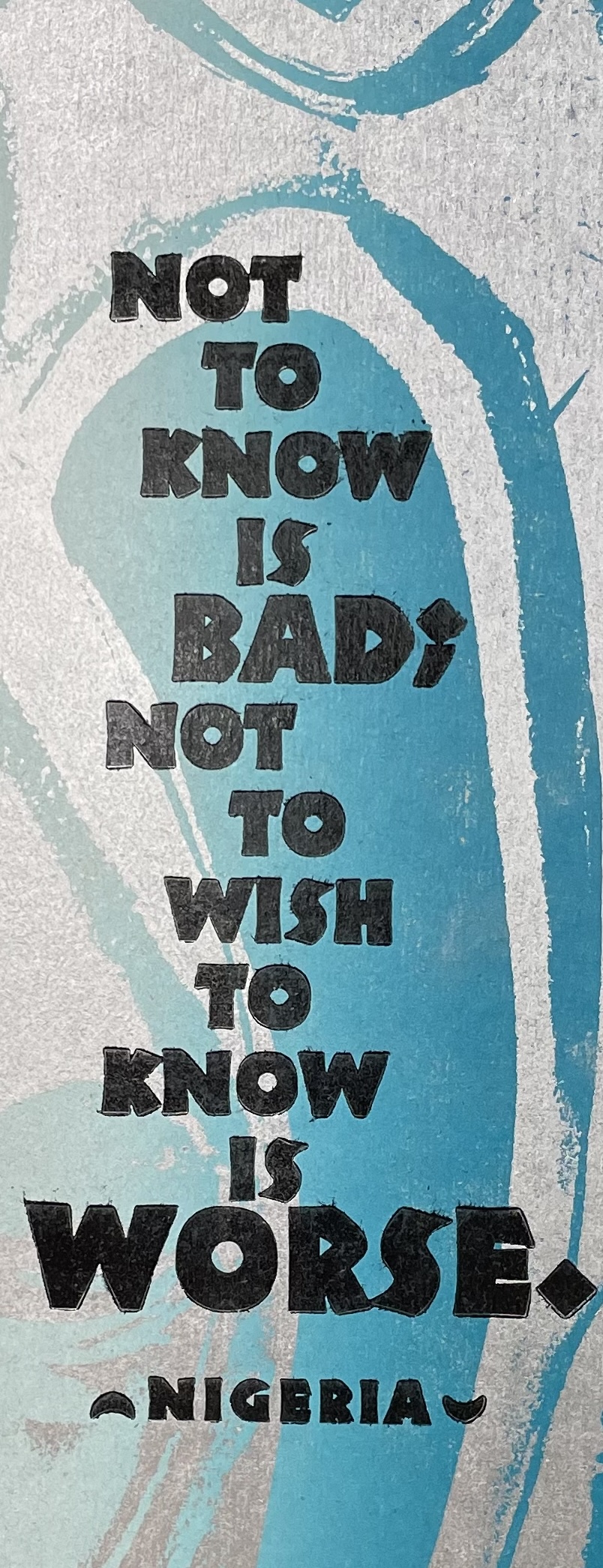

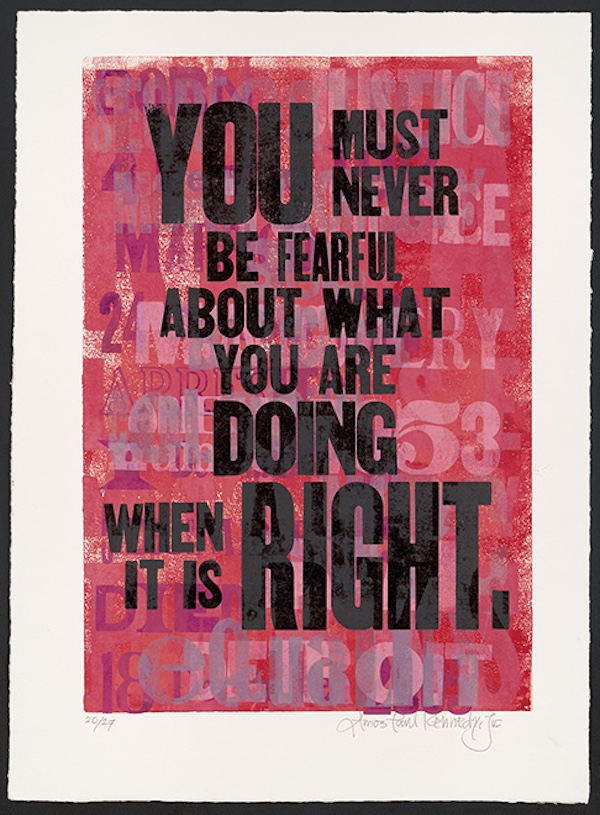

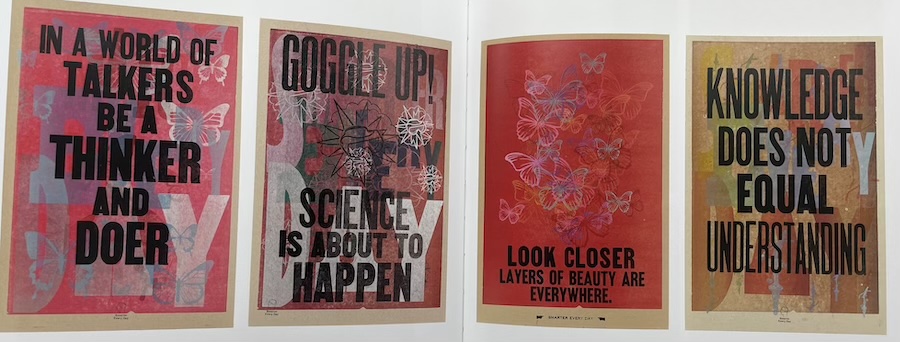

Amos Paul Kennedy Jr., is a Detroit printer and the subject of a recent exhibition and a lavish and beautifully designed monograph Citizen Printer newly published by Letterform Press of San Francisco. The book contains over 500 color illustrations of artist books, letter press posters, postcards, and advertisements divided into three subject categories of his greatest interests: Social Justice, Shared Wisdom, and Community.

On Sunday, September 29th, from 2-4 pm, Amos Kennedy will be signing copies of Citizen Printer at Book Beat’s 42nd Anniversary, we hope you can make it! Signed copies are also available online at the Book Beat gallery.

Book Beat co-owner Cary Loren met with Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr. at his studio to talk about the book and his move from Alabama to Detroit just over ten years ago.

I loved reading your manifesto on printing and your “Lessons on Bad Printing,” a manual on process that puts your philosophy up front in simple direct terms. I knew a bit about Walter Hamady but never knew you studied under him.

Well, Walter Hamady went to school at Cranbrook and Wayne State University.

I wonder if he ever worked on the presses around Cranbrook? At one time they were very active.

He may have known those because there is an intertwined history with Walter and local printers, because he used some of their presses do his early books. And there was a press here in Detroit called Silver Buckle Press, and he was very close with that person. And when the owner died, he willed the Silver Buckle Press to the University of Wisconsin, Madison. And since it has dissolved, it’s now at Hamilton Wood Type & Printing Museum in Two Rivers, Wisconsin.

I saw that Hamady’s archive is now part of the National Library—the Library of Congress.

Yes. They got that from him right before he passed away. Which is incredible.

You had a show there too, right? The one with the Rosa Parks series?

Oh, I don’t recall. It may have been part of a bigger exhibition. I had a couple of pieces. They had a much bigger exhibition, and I don’t know. I don’t know what I did.

Didn’t you go there?

I went there, but that was a while ago, I still don’t know what I did.

Wasn’t that just a few years ago?

No. It was before the pandemic.

[See: Art in Action, Library of Congress]

Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr., artist. Rosa Parks Series, between 2005 and 2019. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Can you talk about what it was like working with Walter Hamady?

I got there just at the tail end of the glory days of book arts. The university never gave Walter the support that he needed to make a very successful program. So, he moved more into collages and other art forms.

His boxes were beautiful surreal objects—like Joseph Cornell.

He made bird houses, big elaborate bird houses for his property. And so, it was fun working with him and good to be there. He had a big barn where he lived, about 30 miles from the campus. And he got there in the late sixties. And in the seventies, that’s when the first wave of family farmers went under. A lot of these were, like, maybe 200 acres, cut, dairy farms, things of that nature. Their children didn’t want to maintain them, so a lot of the faculty in the art department, several members bought them, because just 30 miles away, that was nothing to drive.

What did you learn from Walter?

I learned from Walter to be humble. Walter could be the nicest person in the world. Then other times, he could be a complete shithead. And you don’t need to be that way. You just need to be nice all the time. Even when people aren’t being nice to you.

If you’re gonna be a shithead, be a shithead to the chancellor. Don’t be a shithead to some freshman or a coworker.

No. He wasn’t tough on students. In that respect, he was very generous. But there’d just be days he just was cantankerous. I tell the story where a woman about my age, because I didn’t go back to school ‘til I was 40, and she was quiet. You know? And one day, she asked him the question, “how do you establish a relationship with a poet or author to print their work?” And he looked at her and he said, “Steal it. Just Steal it!” The vein in his neck just swelled up, you know, and I could just see the woman receding. And I’m like, yeah, that’s some shit. And then two weeks later, he comes in and said, “Oh, if you want to start a relationship with an artist, I would suggest that you write them on a regular basis. You just get a correspondence going.” I said, this asshole could’ve said that on the first day. You know?

You started your MFA when you were about forty—as an adult right?

I was fortunate because I had spent twenty years in corporate America. I’ve seen all sorts of things. But I had children and I’m getting ready to go to college. I’m like, hey, but this was an older woman.

Was that difficult, heading back to college at forty?

Well, not really. I didn’t have anything else to do. I got laid off from AT&T. I didn’t want to go back in corporate America, so I said, “I’ll go to school. You know, hide out in school for a couple of years.” At that time, I thought I wanted to make books. And Walter was the premier person in book arts education. And, you know, a lot of the programs that exist now, exist because they were students of Walter’s, they took it on.

Was Walter a major step in finding your direction, because you were printing before then, right?

Yeah. I was printing before then, but I had a job, so it didn’t make any difference. It was just a hobby. And back then I was going to make these artist books.

Was your first book African Proverbs, that one featured in the book?

My first book isn’t even in there. I did a lot of little booklets early on. I gave them all away. Booklets on African Proverbs, Negro Aphorisms. I did some books of poetry by Paul Laurence Dunbar. I just liked his work. When I first started, money was no object because I was working. But then I tried to run a little printing business that was unsuccessful. Then I went back to graduate school because I said I would make artist books.

What was the one you called, “The Idiot Press?” How did that work?

The Idiot Press, yeah. Well, that happened when I took my first class. The instructor said, “If you’re gonna get into this, you need a name for your private press. And the word ‘idiot’ comes from the Greek for private. An idiot in ancient Athens was a private citizen. So, I thought “Idiot Press” would be a good name. I learned that Greek term for idiot in Dostoevsky’s book, The Idiot. An Idiot was a private citizen in Athens who was someone who took all the benefits of the government but didn’t adhere to their laws. It was primarily a male who didn’t follow them. They didn’t participate in the making of it. You know, like, “Oh, I’m just gonna sit here and let you all do the work. And, you know, I’m gonna benefit from your work.” So, I dropped that and went to Jubalee Press. And I also opened up something called Kennedy and Son Fine Printers.

Jubilee was spelled with an a, Jubalee.

I started with an ‘e,’ but then I changed it to an ‘a,’ because of vernacular. That would’ve been the way someone in the late 19th century would’ve come up with.

There’s a novel titled Juba! By Walter Dean Myers.

There’s also a book called Jubilee by Margaret Walker. Juba! is another. And sometimes you find it as a name too.

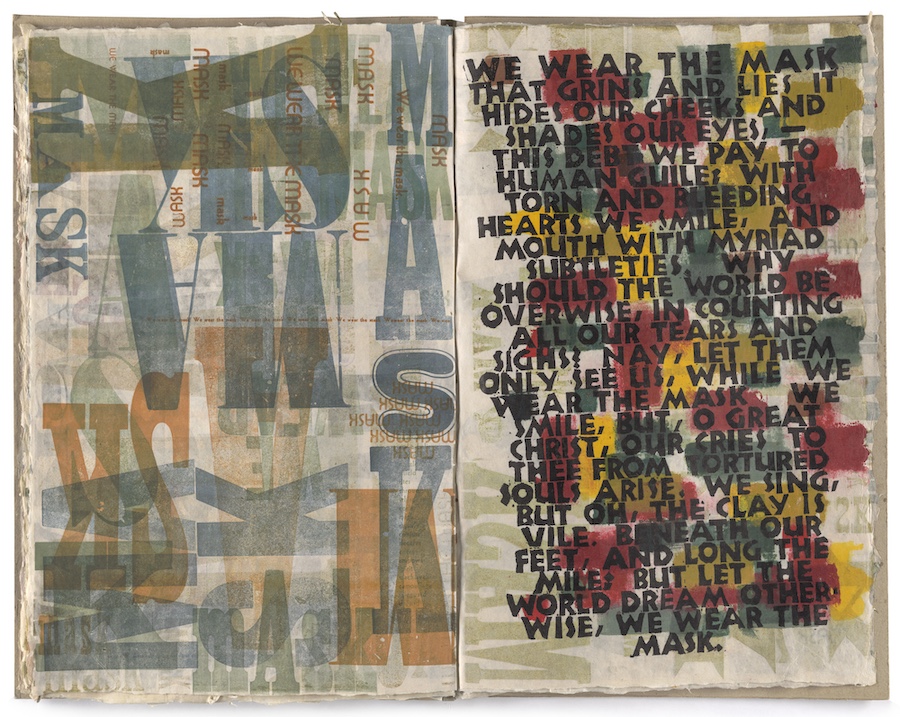

I’d like to talk about your handmade books—it’s so interesting that you’ve had this history of making them, and it’s an important section in Citizen Printer. There’s one book you made called “Riddle ma riddle as I suppose,” that was so cool—where you were over-layering the images and words. I want to talk about super-imposition in your work. You do a lot of layering and it feels like a subtle messaging, or a hidden meaning. I’m not hip to understanding it all, but are these multiple realities you’re dealing with? I don’t know if that’s part of it.

It is part of it. The layers, inform the text that’s printed in black. And so, “riddle my riddle” has, question marks, maybe throughout “riddle my riddle” but there is one layer that has what we would consider to be the title page. Then I printed on top of it and printed on top of it, and there was another and so, yeah, that was a book I did in the mid-nineties. And it was just me having fun playing because I could do it.

There’s only the title page of Fire illustrated. Was that an actual book or a pamphlet?

Yeah, that was a little pamphlet. I don’t think they have all my work out there because I didn’t keep archives.

Was this at Letterform in San Francisco?

Yes, Letterform. I sent everything I had out there. They photographed it—and now they have this massive digital archive of my work. And they’re going to send the original stuff back or they may buy it. At one time they were talking about buying it.

You’ve done many different things with letterpress and the book explores almost four decades of work and then there’s so many places you’ve lived. I couldn’t keep up with your geography.

[Laughs] Yeah. That’s because when people know I’m there, they ask me to leave.

There’s so much going on in the book I lost track, honestly, while reading the biography. Lafayette, East Lansing, Grambling, Maryland, Cleveland, Chicago, Milwaukee, Alabama and Indiana where you taught art classes at Indiana University—it sounded like you had some difficulties, not maybe with the students, but maybe the administration or something?

There was some, but no. I don’t know how you would gather that. I don’t know. Maybe it was because they had difficulties with me, but I never had difficulties.

Maybe there was some racism happening?

No. There was a lot of…I wouldn’t call it racism. I just call it conservatism.

Actually, it had a little to do with race. It’s just that institutions of higher learning are extremely conservative despite what they want to put out there. And I think the art department is probably one of the most conservative departments because they are not needed to be a world class university. They just don’t need an art department. You know? Northwestern got rid of their art department altogether. You need a football team, but you don’t need an art department.

Especially letterpress. We’re talking about an artform that’s been teetering on extinction for so many years. You know?

It should be extinct except for Walter. I think Walter’s impact upon the book arts went really large—and it’s still having an impact.

I think you’re having an impact too.

I’m like part of a third wave. Walter was the first. There were always these private printers, people who did things for, like, the Rowfont Club and the Arion press and stuff. They were like the old world. Right. They were going to buy, you know, another copy of Moby Dick from a fine press for five hundred dollars.

Hamady was really messing with that whole elite fine-press thing, wasn’t he? By adding collage, mixing papers, messing with formats, and over printing things, he was a lot more experimental for a small fine press.

That’s very true. I tell people that the problem with Walter Hamady was that his books were too well crafted to be considered artist books. And too experimental to be called fine print books.

Yes, for sure.

So, he created this whole new area that when people or when a fine printer looks at the book or one of Walter’s books, they can see that that’s a perfect impression. The color on the page is perfect. But like, why does he have this drawing in there or this triangle? Why does he have these bite marks, his teeth mark in the middle of the book? Never do that! But when an artist bookmaker or especially the early artist bookmakers would just spend way too much time, you know, manufacturing the book.

You can also pick up an African vibe from the backgrounds you were doing and with the patterning and color. People don’t always associate bright color with Africa, but it’s right in there, and it’s something I like about the work, that association you throw out.

Well, the association is African, but it’s also, when you look throughout the cultures, you have these primary shapes that are everywhere. You know, triangles are everywhere. So, I tell people, when you see these on an African mask, all these little triangles that they cut out—that’s also just like chip carving in Switzerland.

[Laughter] But there’s symbolism in there too. [While looking over the handmade book Masks in the Citizen Printer book.]

Some, but these are, like, the fundamental circle, triangle, square. That’s as basic as you can get with shapes.That’s a book [Masks] I did at Indiana when I had some free time and set up to print a book. And then all of that was carved out of Masonite.

Wow! And so all the fonts are original too?

Yeah. It was supposed to be based on the Norland font, but it’s all hand carved.

How many copies did you do of Masks?

Maybe about ten or fifteen. Don’t ask me where they are at.

It’s just an amazing thing, looking at this.

And the mask was cut out on Masonite also.

And the book must be pretty large—it’s beautiful.

It’s about 18 by 12 inches, something like that. Somewhere in that neighborhood.

Mask, 2000, Poem “We Wear the Mask” by Paul Laurence Dunbar, text by Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr., Letterpress and relief prints on handmade abaca paper A.P. Kennedy, Jr., Bloomington, Indiana

I was really surprised by that art book section in the book. I’m glad they covered all the bookmaking you’ve done. This one here—the Lynching Burning [Strange Fruit] is amazing.

Yeah. Well that one there, [Strange Fruit] that was my, what is it called? That’s my opus. Yeah.

What do you mean by it’s your opus?

That means that everybody has just one good book in them. That’s my best. And fortunately for me, it was the second book I ever made, so I could give it up.

It looks like a lot of work.

Yeah. Well, it was a lot of fun, a lot of fun. I was just in the basement printing. I didn’t care about the work.

This was made about twenty-five years ago?

No? Thirty years—a little less than thirty years ago.

I love that they included entire book spreads and those big foldouts, there’s a lot of excitement built into the book. This page was the incident I was talking about before with the racism. West Virginia, wasn’t it?

That was Virginia. Farmville.

Sorry. I got that wrong. I had this incident confused with Indiana University. This was an early Confederate flag exhibit where you printed over the flag and that caused some bad reactions—and they returned the work back to you immediately without an explanation.

You got the right idea, because every institution is like that. Yeah. They asked me to do an exhibition.

I didn’t even know this was an early confederate flag.

It is. The Confederacy had lots of flags. And then they went through iterations of the official flag.

The Dixie flag that we think of.

And what we see is the stars and cross, that’s actually the battle flag. Robert E. Lee had his own flag for his headquarters, that was like the standard thing.

And so, you sent them this work for the exhibit and they returned it.

They returned it. Yeah. Well, they have such a proud history of the Confederacy. I figured, what the hell? You know? And the thing is that the people who returned it they’re very proud. I don’t know about you, but I can tell you 100%, I’m a son of the Confederacy. Because prior to, the 1890s, 100%, or 90% of all blacks lived in the Confederacy. My ancestors lived through the Confederacy. And that makes me a son of the Confederacy. You may not like it, but I wanna join! [laughter]

It’s interesting how you adopted all this minstrelsy and old tropes of the South. The watermelon eating derogatory images of black people. You’ve taken all of it on, subverting that in your work. There’s a full page of that stuff.

Oh, yeah. they just did an excellent job, and it engages the reader. The thing that got me was the gatefold.

Oh, yeah, with all those tiny posters.

Here it is. Now that I thought was brilliant.

Yeah but no, that page was making my eyes blurry. [laughter] Honestly, it was like a little too much, but it’s great. It’s just so much work to look at. Hundreds of images in that one spread.

I call it fun. You call it work.

Well, it’s just what you do. I’d like to ask you about the Peace Corps. How was that?

I spent about 18 months in Liberia, 1973. I was part of a program. And after about 18 months, I had enough of it, so I said I’ll come back home and start my life, become a professional, doing all the things that my generation is supposed to do. Get married, have children, some college, retire, and go down to Florida, play golf forever.

Was there anything in the book not included that you wanted? Something overlooked?

Not really. They covered just about everything. They did a full court press, as I guess you would say.

The photos they took in the studio are great.

They hired a really good photographer, came in from New York to take all those. Did them all in, like, two or three days.

It really works and gives a good feeling for the space.

And they did excellent color separation and color correction.

This is one of the best art books of the year, I think, in design and content. I’ve never seen anything like it.

Oh, okay. Like they said, “We’re gonna make 5,000 copies. I said, ‘I don’t know if you’re gonna be able to sell 5,000. I only know a few people…’ [laughter]

I think you’ll be okay. I love how they did the binding.

They asked me about the binding, and I said I wanted it this way.

It’s very cool.

There was a wave in the early 2000s where a lot of books came out like this.

We have a few titles done like this. I like it for art books because you can lay a large book completely flat without breaking the binding. It’s flexible. I love how they imprinted the cover title too – like it’s in letterpress.

Now this was produced in China, and they did all that. I didn’t print that date. For sure. But they did do an embossed letterpress somehow.

As a last question I wanted to ask about your move to Detroit. It’s been about 10 or 11 years now. What’s your impression of the city—what do you make of it?

Well, I think that it’s potential wasted. The longer I stay here, the more I see how entrenched the power structure is to a model of development that failed them once and will probably fail them again.

There are a lot of ideas out there, but people are uncomfortable trying them because the ideas could fail. But the power structure’s very comfortable doing something that has already failed and will probably fail again. And so, I’m just amazed. Detroit has 700,000 people. Now let’s just say 600,000 people in it. Of that 600,000, there are at least 60,000 that make a six-figure salary living inside the city. If those 60,000 people were living in a town, there’d be a Target. There’d be a Walmart. There’d be two or three Krogers. But those industries have said, oh, no, although we do have a critical mass to support a store, we don’t want to put anything in Detroit. My brother lives in a town. I don’t think it’s a 100,000 people and they have four Walmarts.

Well, one of the problems is that Detroit’s space is so spread out. It’s huge.

Oh, that doesn’t make any difference. Yeah, it’s spread out, but it’s still got the people. Do you actually have to have each Walmart, you know, 4 blocks from each other? It isn’t that spread out.

In the book, towards the end of one of the essays, you talk about building a community center here for people based on learning letterpress.

Initially, I wanted to do that but…

Wait a minute. I know people who would get in line to be your students right now.

Well yeah, but see, the thing is that’s too much formality. Running something like that is a full-time job and so you’re no longer a printer, you’d be an administrator. Or you have to hire administrators, so suddenly, you got to make 50,000 more dollars and I don’t want all that pressure. I just went back or fell back on what I’ve been doing since I moved from Alabama. And that is people who are interested come, they knock on that door. I open it up and say, come on in. They call me, they email me, and I said, well, I’ll be there, at 1 o’clock, and if they show up, I take time and let ‘em make something. And if I never see them again, that’s not my problem. They wanted the experience. They got the experience. They went home and said, well, that isn’t for me. So, they made a conscious decision.

What I’m trying to say is that I want you to have the experience. And if you say you never want to do it again that is okay. But you can’t say, well, I wanted to do letterpress, but I couldn’t find any place to do it. Some people just want to have that initial experience. And then some people, go yeah, I’ve got to do this forever. And they will come back. At some point, once this place is cleaned up, that mix is going to happen where there’s somebody who comes by.

People will want to learn from you—and this book will help draw people to your studio. A lot of people. Amos, it’s time to get prepared.

Well, I’ll tell you, I got rid of my website. I’m going to get rid of my phone number. Then I’m going to get rid of my email. Oh, I’ll be prepared for it! [laughter]