I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, ephemeral, small press, comics, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, “This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.”

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If you notice titles unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at: i arrogantly recommend…

Story of O: Eros, Paris & Surrealism

Story of O: Eros, Paris & Surrealism

Reese Saxment

Black Scat

In 1950, a divorced mother in her mid-40s, living with her mother and teenaged son, feared that her older lover—himself married with an ill wife—was turning his attentions to an erotic competitor. To re-direct his interests toward her, she began writing a series of erotic encounters about a young woman and her lover’s demi-monde. Her older lover was so impressed by the letter that she handed him in 1951—about 60 pages—he asked for more, which she provided. She also agreed to his proposal to find a publisher for the book, which would be presented under a pseudonym. In 1954 the erotic account was published to much admiration and disgust and attempts to suppress and expand, but ultimately helping to usher in a new age for Western feminism, female agency, eroticism, and pornography.

The book, of course, was Story of O, an explicit depiction of a woman’s encounter with bondage and discipline and sado-masochism to please her lover. Erotica and pornography had been around have been a part of the human cultural landscape since at least the time of cave paintings. The dark side of sexuality had been well catalogued in the 18th century by the Marquis de Sade, so that wasn’t what made Story of O novel, either. The outrage and shock it engendered among those in French society who could still be shocked and outraged owed to the story’s purported author, a woman, for one, who voluntarily subjected herself to sexual, emotional, and physical debasement as a sign of love for her chosen man. Although the book was praised for its understated prose, many readers were skeptical that a woman could write such a story. That women may find life-fulfilling satisfaction in complicity with their own debasement is an idea of agency that sits very uncomfortably with feminists and their allies in the U.S.

Reese Saxment’s Story of O: Eros, Paris & Surrealism is an excellent work of historical and cultural research, telling not merely the story of how a dirty book came to be published but providing crucial contextual evidence and assessment about the larger political-historical events that shaped Story of O’s ethical concerns, as well as its longer-term effects and the ways in which it continues to be plumbed by scholars for its psychological depths.

Post-war, figures such as Sade and Freud, and members of the Surrealists pointed to repression as a personally and culturally malforming mindset that lead to the horrors of WWII. In particular, they exhorted on the dangers of repressing sexual urges in the name of virtue, as defined by, say, a church or government. Sade and Freud argued that sexual urges are innate, intuitive, and often aggressive. The suppression of sexual aggression, for them, became manifest other forms, such as war—the activation of entire populations for murderous intent against each other—waged largely over cultural differences in how, to what extent, and for what purposes our urges are suppressed. For Sade, crimes against humanity are significantly lower when individuals are allowed to act as they please than when groups are forced to act as they are told.

Agree with that position or not, many people who lived through WWII found something familiar in Sade’s and Freud’s assertions with their own thoughts and experiences of the war and the motivations it stirred. For Saxment, repression and its consequences are expressed in Story of O in metaphorical and allegorical terms that resonated with French readers aware of the erotic frissons associated with resistance and collaboration during the war, whether giving for a cause, despite the life-threatening risk, or ceding to the enemy, because of the need to survive: “As [the author of Story of O] understood, ‘it is not the people who read Sade who made the concentration camps. Those were the people who had never read Sade.’”

So, who wrote Story of O? Everybody assumed, correctly, that Pauline Réage, the byline on the title page, was a pseudonym. Saxment shows that while the inner circle of France’s literary culture knew who wrote the book, most people did not. Waiting until she was 86 to publicly confess to her authorship, Dominique Aury, everybody’s notion of a button-down, proper woman.

When she was younger, Aury held important positions in the top echelon of France’s publishing establishment (and was one of the rare women in the industry of the time allowed to do so), including Gallimard, as translator, editor, and judge. (Ironically, Albert Camus—one of those who doubted that O could have been written by a woman—sat on the editorial board of Gallimard that voted to approve the novels proposed for publication along with Aury.) Her lover was Jean Paulhan, more than 20 years her senior and married to a woman invalided by Parkinson’s. Paulhan had lead positions at Gallimard, Nouvelle Revue Française (one of France’s best literary magazines of long standing), as well as for a publication he edited for the Resistance, which is how he met Aury.

Their circle of friends, lover, political allies, co-workers, and co-conspirators overlapped along right-wing and left-wing politics before, during, and after the war, and included Gallimard acquiescing to Nazi demands to publish their garbage because they allowed him to publish what ideologically they found degenerate. So, yes, Gallimard collaborated with the Nazis—but for a grander purpose. Many other individuals and organizations sacrificed principles with one hand to sustain other principles with the other hand. Sacrifice, complicity, brutality, and satisfaction run throughout Story of O.

I can imagine future work that may end up filling in details and perhaps correcting errors related to information reported here, but I think Reese Saxment’s Story of O: Eros, Paris & Surrealism is model of cultural history and literary studies: broad in his scope, intelligent and even-handed in his assessment, and entertaining in his retailing, to boot.

The Science of Love and Other Writings

The Science of Love and Other Writings

Charles Cros/Doug Skinner

Wakefield Press

Charles Cros (1842-1888) was born into a creative family that included artists and scientists, sometimes in one person, as with Cros himself. Twice he almost succeeded in gaining patents for devices he invented—one for color photography, the other the phonograph—but, as with his poetry, despite his intelligence and talent, Cros was unable to make a stable living at either. Some of his writings, included in The Science of Love, are proto-science fiction, but his tone is ambiguous enough to make difficult to tell which points he is serious or tongue-in-cheek about—which is to say that a quality of ridiculousness pervades much of his writing, but a ridiculousness that is of a piece with the assumptions of his time.

In the title essay, for instance, he lets us know of his familiarity with the principles of physics, mechanics, and the scientific method (define a problem, propose a solution, refine the results and repeat). He sets out to study less the body’s physical responses to sexual stimulation than to give scientific shape to sex’s emotional counterpart, love. However, he faces the problem of his own physical lack of attraction that would make him an ideal lure for a woman who might be enticed to have her physiological reactions recorded by attached scientific apparatus during coitus:

I want to study love, not like the Don Juans who amuse themselves without writing about it, not like the writers who mistily sentimentalize, but like serious scientists. To record the effect of heat on zinc, you take a bar of zinc and heat it in water at a temperature rigorously determined by the best thermometer possible; you measure precisely the length of the bar, its resistance, its sonority, its heat capacity, and you do the same at another temperature, no less rigorously determined.

But he won’t be able to test the effect of heat on his own zinc bar until he can first “make myself worthy of feminine dreams.” Determining that his worthiness depends on two qualities—the ability to play Chopin on the piano and write acrostic poetry—he approaches two experts in their respective fields get his skills up to speed, and then proceeds to apply these skills in the presence of potential women subjects. As with any scientific test, negative results accumulate until he refines his methodology sufficiently and finds a subject willing to have her body strapped to various contraptions, i.e., a potential bride named, appropriately enough, Virginie.

The first apparatus he attaches to Virginie is disguised as a cameo with a picture of himself: “The portrait contained, concealed between an ivory plaque and the enamel, two maximum and minimum thermometers” that allow him “to verify the modification in the normal temperature of an organism affected by love,” temperatures records and dates during pretenses to have Virginie return the cameo to him. He soon supplements the cameo with a cardiograph “adroitly inserted between her tenth and eleventh rib,” which “record[s] the visceral expressions of the situation.”

As the seduction advances, they enter his bedroom whose

copper-lined walls prevented any contact with the atmosphere; and the air, first at it entered, and then as it left, was rigorously analyzed. The potassium solutions in the ball devices revealed to expert chemists, hour by hour, the quantitative presence of carbonic acid.

And so forth. Implicit in Cros’s faithful following of the scientific method is the absurdity underlying his rationalization, although I’m not sure Cros is entirely aware of the ridiculousness of his assumptions.

“An Interplanetary Drama,” another story in the collection, is set in the year 2872, a time in which astronomers have developed their profession into a cause requiring celibacy (!?). The settled order is thrown into chaos, however, the day a young, untrained male astronomer (and thus not yet sworn to celibacy) encounters—via telescope—a woman of “extraterrestrial beauty” (emphasis in the original)—yes, a Venus from the planet Venus. The account of their doomed love ensues.

In Cros’s universe, all entities—animate and inanimate—seek love, or at least its nearest cousin, sex, including rocks. In “The Stone Who Died of Love,” for instance, a piece of flint, whose name translates as “Alfred,” attempts to seduce a fissure in the ground, named “Augustine,” by singing an aubade “in the void redolent with magnetic oxide.” To complete the seduction, Alfred then “used the imaginary coefficients of an equation of the fourth degree.” Why? “It is known that in ethereal space one obtains in this way incomparable fugues.”

For readers both interested in science and unperturbed by the aspect of casual fugues between consenting rocks and fissures and related phenomena, The Science of Love is your book. Hats off to Doug Skinner and his relentless quest to find and translate into English unknown and little-known gems from the French humanities.

Return to Romance! The Strange Love Stories of Ogden Whitney

Return to Romance! The Strange Love Stories of Ogden Whitney

Ogden Whitney

NYRB Comics

Fans of kitsch, comics, feminism, and popular culture/sociology/anthropology will find much to enjoy and be appalled by in Ogden Whitney’s representations of mid-century heterosexual love. Whether approached for its kitsch value or the frisson of its dispiriting sense of female value, Return to Romance! delivers.

In one tale, a wife loses her husband after allowing herself to become frumpy merely because she scrubs floors all day on her hands and knees (there’s agency for you!). In another, a couple discover that it is possible for “homely” people to find true love—once each gets over the other’s homeliness (“The Red-Haired Boy and the Pug-Nosed Girl”). Female readers worried that their inherent stupidity hides their equally inherent charms will find hope in the case of Margie, who proves to herself and others that just because she can’t count change or complete even the easiest classes in high school (she drops out), it’s her quality of honest forthrightness (and good cooking skills) that will land the industrial capitalist with a PhD. And so forth.

The action is stiffly but dramatically composed, drawn in primary colors and black printed on newspaper. Ogden Whitney draws as if curves don’t come naturally to him, but despite that technical limitation, he breaks up the pages well, balancing the visual elements without uniformity and directing the eye to the stories’ most compelling elements in line with the narrative arc.

Masters of the Nefarious: Mollusk Rampage

Masters of the Nefarious: Mollusk Rampage

Pierre La Police/Luke Burns

NYR Comics

The best absurdities are those that hew most closely to reality, yoking high culture and language to low, following “reasonable” assumptions situations to their (il)logical conclusions, often in understated, matter-of-fact tones. Masters of the Nefarious begins with a tidal wave that destroys much of a string of tropical islands called Maluku, the islanders’ fates only worsened by gigantic mollusks washed ashore that devour the tsunami’s survivors. Meanwhile, a large, quadrilateral metal frame hovers in the sky over another part world. Surely, the two incidents must be related, and only the Masters of the Nefarious can solve the mystery!

The Masters of the Nefarious are a trio consisting of the mutant Themistecles twins—the lantern-jawed Chris and Montgomery—and their mottle-fleshed friend Fongor Fonzym, who drives out to meet the twins on his steerable staircase to discuss what to do after discovering that the antediluvian mollusks attacking the inhabitants of Maluku are called Sukoïds.

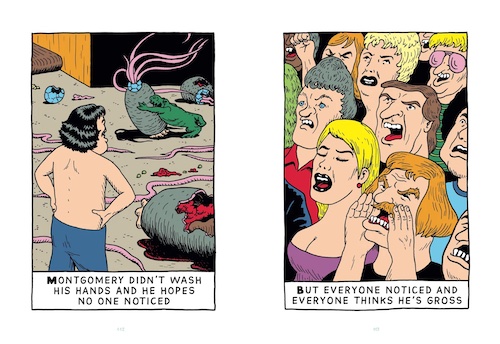

En route to setting world affairs aright again, Montgomery is crushed by a falling concrete slab (or is he?), Chris heads to Mexico to have his penis enlarged, and Fongor goes home to refold his t-shirts. Fans of the British cartoonist Glen Baxter—a master of Dada-esque absurdities—will recognize in cartoonist Pierre La Police’s images a similar approach to narration: A single image per page with an explanatory caption below it, akin to illustrations found in such old adventure books as the Hardy Boys but accompanied by text saying things like “Montgomery is thirsty but a pre-existing condition prevents him from refilling his canteen,” or “Like all mutants he transforms into sort of a yellow hulk when he drinks schnapps,” or “He also gets enraged when he see stemmed glassware.” Will the Master of the Nefarious stop the Sukoïds in time to save the world? Hey—no spoilers here!

Translator Luke Burns earns bonus points for imbuing the book with humor that travels well.

The Inhumans and Other Stories: A Selection of Bengali Science Fiction

The Inhumans and Other Stories: A Selection of Bengali Science Fiction

Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay (editor and translator)

MIT Press

The Radium Age series of science fiction novels and short stories inaugurated and edited by Joshua Glenn and published by MIT focuses on science fiction written between 1900-1935, the era between the end of Victorian science romances (which would include such writers as Jules Verne) and the start of the Golden Age (when Astounding Stories editor John Campbell successfully formalized the genre’s elements). During this intervening 35-year span, science fiction was still an amorphous thing, serving to provide writers with terrain for thought experiments about Earth-bound social and physical science conventions. By gussying up the actors in alien form, the distancing effect helped “make it new” (which became Modernism’s rallying call), whatever it was. “Speculative fiction” it was, more an impetus to creation than a form to be filled, as it later became.

As an invitation to thought experiments, the temptation to speculate attracted such mainstream authors as Edith Wharton and G. K. Chesterson. In addition to contributions from women writers, the Radium Age also attracted writers from around the world—two sets of writers largely absent from the world John Campbell made. The Inhumans—marking the first translation and publication into English the stories of several Bengali science fiction writers—sets out to correct that skewed, false impression of who contributed to exploring the fecund territory of speculation.

The title story, by Hemendrakumar Roy, is a lost world tale set in Africa and told by an Indian hunter who, having experienced the thrill of killing India’s large game, sets out for Lake Bunyonyi in Uganda. “The Inhumans” is a short novel, giving Roy the time needed to slowly unfurl his narrative as it segues from describing the dangers of hunting real animals to the fantastic arena of hunting creatures more dangerous and bizarre, starting with an encounter with a 16-year-old girl raised by gorillas and ending with the strange world of the Jujus. Although the girl’s presence turns out to have a “rational” explanation, the deeper into the jungle land the hunter goes, the more ambiguous becomes the distinction between “rational” and “superstitious” arguments, the more concrete and plausible the previously unbelievable becomes.

During pursuit of a lion he had wounded, the narrator of “The Inhumans” finds the diary of a dead man in a lion’s cave. As coincidence would have it, the dead man was Bangla, too, making his diary possible to read. The diary describes the world of the Jujus—an advanced civilization of beings of Bangla descent who have modified their bodies as part of their evolutionary advancement. They are now boneless creatures that live in . . . barrels.

From the distance of 90 years since this story was published, it’s hard to tell how much of the diary’s narrative we are intended to be frightened or amused by. Descriptions of unusual objects that context would suggest should be understood as horrifying come across instead as comically exaggerated—eyes bug out, limbs and torsos sprout weird buboes, and so forth. The action is plentiful—and plenty implausible—without reading as a proto-Bollywood production (as the Mahabharata does), although it does feature several songs.

The eponymous voyage Jagadananda Ray’s “Voyage to Venus” (1895) occurs via a dream in which only one side the planet ever faces the sun. Upon arriving on the dark side of Venus, he is immediately welcomed by a group of Yeti-like creatures, primitive yet kind. The creatures coax the narrator to a cave, from which a close friend of the narrator’s emerges (!). Of course, the planet’s atmosphere has breathable levels of oxygen and the soil grows digestible types of plant life. After several months of exploring the dark side of the planet and learning the Yeti language, the pair decide to make the 1,200-mile hike to the sunlit side. One of the Yetis, whom they have named after the Hindu Ghatotkach, insists on going with them. They agree to the wisdom of being accompanied by an escort familiar with the planet, accept his offer—and immediately treat him as a servant and load him with their travel gear rather than carry it themselves. (Clearly, colonial impulses aren’t products only of Western imperialists.)

On the sunlit side they discover another race of beings—not dark, hirsute, and clawed like Ghatotkach and his kin—but attractively human-like and technologically superior to both Ghatotkach’s race and the Earthlings. However, these Venetians recognize the Earthling’s superior breeding and intelligence, and treat them as equals rather than lade them with tasks. Eventually boredom sets in, and the narrator’s dream comes to an end.

Rounding out the collection are “The Mystery of the Giant” (1931) by Nonigopal Majumdar (which provides a pseudo-scientific explanation for Bengali “spirits”) and “The Martian Purana” (1931) by Manoranjan Bhattacharya (in which Space-Age versions of major figures from the Mahabharata and Ramayana confront autonomous mechanization on Mars).

A lot of fun, this lot, with breezy narratives told enthusiastically.

Moieties

Moieties

Elytron Frass

Subtle Body Press

Elytron Frass’s Moieties is a formally innovative and dense novel combining science fantasy and occultism, telling a story via three separate teams of narrators telling their stories simultaneously on each page.

The story’s protagonists, identified only as L and R, are conjoined female (L) and male (R) twins, connected at the skull. Theirs is the novel’s primary narrative source.

The secondary narrative consists of italicized endnotes written by the twins’ surgical team at the bottom of each page. The surgical team separates the twins less for the sake of separating them than to study how the surgery affects the twins’ previously shared cognitive functions: What happens to the conscience and soul of each twin because of the separation. The twins are also members of a minority religion, which seems to serve as another reason for the secular scientists to experiment on them.

After their surgery, L and R explore the islands around them known as the Seven Enigmas. The islands’ poisonous atmosphere first alters the appearance of exposed flesh, then kills whatever is exposed to it. The twins communicate with each other telepathically and interpret their experiences through the lens of their religious upbringing.

The tertiary narrative is written, like the secondary narrative, by anonymous parties, whose identity is guessed at from the content of what they write. In this case, the narrative seems to be by those parties given to (re)unite the cognitive and spiritual lives of L and R. This supernatural narration is handwritten as marginalia. Moieties has two parts consisting of pages 1-46 and 46-1, both parts including handwritten marginalia written on one side of the page that is mirrored (i.e., reversed) on the other side (the reflection switching from the recto to the verso page after the halfway point), beginning with L’s narration, which dwells on R’s communications with her.

The surgeon’s note hints that something might be off in the relationship between L and R: “Subject L is being prepared for a novel separation from Subject R, her conjoined form.” Note that the surgeon does not say that the two will be separated from each other but that L will be separated from R, as if R lacks subjectivity. This attitude is reinforced by L’s claims that, while the two may be conjoined and thus identical, they are nonetheless “ever asynchronous—two incompatible, opposite unequivocals,” begging for “defilement and erasure by [L’s] fervent hands.” As the novel progresses, the story is also told from R’s point of view and the point of view of the twins as a single consciousness.

Each enumerated page in the novel has its double, so that one page feeds back into the other, like a Moebius strip. Specifically, the statements making up the handwritten marginalia on each page are completed by their twin page. Thus, the handwritten marginalia of L’s page 34 is completed on R’s matching page 34, running from the top of L34 to the top of R34, down R34’s side, then upside down along the bottom of R34, and continued to completion back on L34, also upside down along the bottom then one side of the page. Here’s an example. (Breaks from page to page are indicated by double slashes. All irregular spellings and punctuation are the author’s.)

WE WERE CAREER SCIENTISTS EMPLOYED AS // NEOPHYTE THEURGISTS BY AN ANDROGYNOUS FRANKENSTEIN OUTSIDER TO BIND THEE DISPARATE HALVES OF THIS BOOK WITH THEE RESOLUTE EFFORT TO ACTIVATE // METAPHORICAL PHILOSOPHERS STONES THAT WILL BEAR AN ILLUMINATE THEE ULTIMATE COMPLETENESS OF INCOMPLETION

While the concerns of the occult don’t compel me as a reader, nor do discourses about the science/religion dichotomy, I appreciate and admire Frass’s attempt to represent in physical form the psychological and spiritual relationship between the twins, which is a success. An aspect of Frass’s writing that could be improved would be to replace adjectives (which run too thickly in for my tastes) with verbs. For every adjective used to describe a noun is a noun untapped that would make the visual elements do work. Thus, scenes that are visually rich may contain little action, despite their profusion of, say, gore, body parts, and wyrms. Frass clearly has talent; it just needs some refinement to bring about narratives complex, compelling, and wholly satisfying.

How I Killed the Universal Man

How I Killed the Universal Man

Thomas Kendell

Whiskey Tit

How I Killed the Universal Man is the title of a video game in this novel of the same name a video game more talked about than encountered in the novel’s pages.

Taking place in the near future, How I Killed the Universal Man involves John Lakerman, a reporter for a Vice-like publication called donkeyWolf, who investigates and writes about odd and disturbing trends in subcultural practices. In How I Killed, the subculture includes drugs developed and tested sub-rosa by Big Pharma.

The novel’s near-future also includes nanobots that can create and distribute, once injected in a human body, a subcutaneous graphene net able to communicate with any number of computer apps that, for instance, supply the person with the net information about almost any subject the person has a question about. With the graphene netting, a person has a form of distributed consciousness akin to that of an octopus, whose brain is distributed throughout its body rather than centrally located, as with our head. The bots are also able to create chemical reactions in the body like the dramatic overload of LSD hallucinations to behaviors far subtler.

John Lakerman has contracted to write an exposé of a new drug in development, posing as a test subject whose effects he will monitor and report on while trying to dig up dirt on the company and its founder. His investigation is prompted by the deaths of some of the doctors involved in the trial study and the disappearance of the pharmaceutical company’s founder. The effect of the drug is controlled by doctors working for the company, who can manipulate its affects from afar via the graphene net.

Although Lakerman is assured by one of the doctors that the effects can be turned off at any time before the end of the 30-day trial, and that he can go “offline” any time he wants, those claims seem increasingly suspicious as time passes. The interactions among the various other drugs he takes during his investigation as well as the technical glitches affecting him as his body and graphene net slowly integrate show that he has less control over his thoughts and body than he might otherwise hope for. Determining who is controlling the show and for what purpose is a matter of will when Lakerman’s brain and body seem to be melting.

The Unfinished Life of Phoebe Hicks

The Unfinished Life of Phoebe Hicks

Agneiszka Taborska / Ursula Phillips (text) and Selena Kimball (collages)

Twisted Spoon Press

The American Spiritualism movement began in New England in the mid-1800s, its most defining features being séances held to commune with the dead. The séances were led mainly by women mediums, women believed (by others, sometimes by their own assertions) to have the power to talk to the spirits of dead people—often a spouse or parent of the person paying for the séance. Apparently, the ability to talk with the dead wasn’t sufficiently startling for the paying mourners, so ethereal noises (such as knocks on the wooden table participants sat around) and vomiting ectoplasm on the part of trance-state mediums were added as extra proof of the communion’s authenticity. Ectoplasm was allegedly a material manifestation of the spirit evoked, ejected through the medium’s mouth to the shock and paid admiration of the guests. Of course, none of the guests were curious to verify the ectoplasm’s make-up to touch it, the ectoplasm looking more like the alien vomit it was purported to be than the mixture of egg whites and muslin it really was.

One of these mediums, Phoebe Hicks from Providence, Rhode Island (where competition among local mediums for steady employment was fierce) began her career inadvertently after she was photographed while ill. Specifically, after eating a bad batch of fried clams, Hicks rushed home an endured several violent bouts of vomiting. A local photographer happened by, took a picture of her head suspended above a bowl of vomit, printed the photograph, and distributed as documentation of a medium communing with ectoplasm. Confronted by the photograph and the questions locals had about it, Hicks was easily swayed to change careers. What her former career was isn’t stated by author Agneiszka Taborska (admirably translated by Ursula Phillips), it seems that routinely vomiting ectoplasm was a significant step up for a single woman living alone. (The book is presented as a fictionalized biography, but I can find no evidence that Phoebe Hicks actually lived.)

Phoebe Hicks’s origin story isn’t examined for holes by Taborska, starting with the “happenstance” act of photography, which requires us to believe that some guy (probably a guy) just so happened to be lugging around a big, heavy, daguerreotype camera and its wooden tripod through the streets of Providence, was close enough to the windows of a house to see a woman vomiting inside, decided it was a novel photo-op, set up his camera, and patiently waited for the 30-minute exposure to elapse. Call clam puke “ectoplasm” and sell the results in the form of postcards to the tourist trade. (“Wish you were here!”)

Rather than interrogate the claims and actions of Phoebe Hicks, Taborska is instead interested in examining parts of Hicks’s life as they reflect and add to the cultural milieu of her time. Rather than a birth-to-death biography, Taborska reflects on key moments from Hicks’s life, her guests, her town, and the phenomenon of Spiritualism. Taborska’s reflections are as brief as a paragraph and no longer than three pages, often supplemented with Ursula Phillips’s excellent black and white collages, which convey the weirdness and unease of the séances and Hicks’s spiritual state in images similar in cohesive, organic oddity as images produced by, say, the Brothers Quay or David Lynch. The Unfinished Life would feel even less finished without Phillips’s collages, which are integral rather than supplemental to the strange story as it unspools.

What is not strange, what feels contemporary about this fictionalized biography are the reasons why almost any woman would without economic and social security: In their “trance” stage, with spirits speaking through them, mediums could say things to their guests they otherwise couldn’t get away with. A woman could be “odd” and not have to worry satisfying a whole set of social conventions that otherwise would leave her destitute. In that regard, yes, the dead still speak to us.

The Sunset Suite

The Sunset Suite

Rhys Hughes

Gibbon Moon Books

This follow-up to Hughes’s Weirdly Western Tales consists of tales inspired by the following premise, stated at the book’s onset, as two cowboys sit around a fire, drinking coffee. One says to the other,

You know something, pard? This coffee tastes not just like coffee but also like something else. I think it tastes like a story, a different story with each cup, but a very short story every time because the cups are so small. And that’s not a normal thing for coffee to be like. I won’t say the situation is worrying, no siree, but I might venture the opinion that it’s highly unusual. The cup I drank just now tasted like an anecdote about a mule.

His confrere agrees with the assessment, and the rest of the book collects the anecdotes they exchange between cups of coffee—26 cups, to be precise.

And so, dear reader, you find yourself regaled with tales about cannibals and banjo players, uses for clay in prisons, a talking sombrero, a temperamental ragtime pianist who learns to compose himself, a Sioux named Boy, a stranger with a “stride bold and lengthy, like an epic poem printed in heavy type,” et cetera, as Rhys Hughes plays with conventions, makes puns, and has fun in general (with a kernel of truth).

Here is the introduction to “Tumbleweeds”:

A large tumbleweed can be utilized as a getaway vehicle. I often take advantage of this fact. To summon a tumbleweed, one must tell a joke that isn’t funny. I robbed the saloon, the sheriff is coming. How do you warm a frozen cowboy? Yee thaw! and I am gone. The tumbleweed rolls faster and faster and I am safe inside it, turning over and over until I am dizzy. This isn’t pleasant but it’s still better than spending my time behind bars.

Which sets us up for the pun that follows about the saloon just robbed: “Barmen spend a lot of time behind bars. . .”

Joy and enthusiasm for storytelling and modes of storytelling permeate these tales, which are often funny but never mean-spirited, always inventive and silly.

Faraway the Southern Sky

Faraway the Southern Sky

Joseph Andra/Simon Leser

Verso

Born Nguyen Tat Thanh but dead as Ho Chí Minh (with 175 other aliases in between), the future president of North Vietnam arrived in Paris around the end of WWI as a radicalized youth driven to bring attention to the plight of the colonized peoples of Southeast Asia, seeking Marxists and men with political affiliations to help bring about human rights and democracy to his people. His pleas were uniformly rebuffed by would-be fellow travelers who told him nobody was interested what happened in Vietnam. After several years of going from political group to political group, taking on menial jobs and living in squalid apartments, he finally—and secretly—left for Russia, where apparently sympathetic ears could be found. I say “secretly” because although he was a political unknown without any power or connections, he was constantly tailed by the police and other French governmental secret services. Their reports provide most of the information about Ho this slender book (80 pages) is based upon, with novelist Joseph Andras filling in speculative details and conversations.

Shy but adamant, well-informed but unpersuasive, the life of Ho as outlined by Andras, courtesy of French security documents, is one of a young man driven by political notions of justice and fairness, a gentle monomaniac who seems to have even spurred the advances prostitutes and potential lovers in preference for his drive to establish security and dignity for his people. (The very “seems” is deployed here because even France’s surveillance reports remain ambiguous regarding this point.) But Andras writes not just a partial biography of the political dissident but also a historical novel tying Ho’s past to our present, following Ho’s path around Paris, locating the places he lived and worked and relating them to current events in France. (“Current,” regarding the time of the novel’s writing, being during the uprising of the “yellow jackets”—rural commuters who protested the rise in fuel prices by donning the yellow reflective jackets named by the French government as the article of clothing for motorists to wear during emergencies.) Simon Leser’s translation of Faraway brings an understated assurance to Andras’s narration of a ghostly figure who presided over decades of ghastly warfare.

Territories of the Soul/On Intonation

Territories of the Soul/On Intonation

Wolfgang Hilbig / Matthew Spencer

Sublunary Editions

Greys, greens, and blues comprise the landscape of Wolfgang Hilbig’s East Germany, as presented in these vignettes and poems—the greys of industrial decline and waste, the greens and blues of treetops and bodies of water suggesting the better alternative offered by nature, but foreshadowing their own impending decline and destruction. Clemens Myer, author of While We Were Dreaming, is another writer from the former East Germany who also describes the place in similar terms—a dead land inhabited by dead souls. With Hilbig, we have narrators who work long shifts at dreary jobs housed in sunless buildings, narrators at risk of losing their meaningless jobs, the threat of further isolation and personal deterioration the certain result of unemployment. Even Charles Bukowski faced rosier presents and futures than the ashy remains of fascistic communism offered its citizens.

Since I moved to L., to the dirty area west of this apparently even more unreal city . . . every night the daemons test me. . . Here in L., my existence is laughably, unbelievably recalcitrant; the well-known dreamy moods, onto which such beautifully colored nights can be transposed, even if they can be read from the papers described in their course, are thus the most absurd thing I experience. Reason compels me to suppose my mind is out there, in that far distant elsewhere, which tints me with the lambent light of the window’s refection. . . in any case, nothing prevents me from imagining myself in the blue of that immaterial sky, in some unknown upper region, above the sea and clouds, a beacon which I cannot recognize. . . what is preserved of me here is the opposite of presence.

A laughable existence, hope an absurdity, a historical materialism hostile to immaterial souls. Territories is a short book (45 pages) that unfolds to psychologically immense horror. Matthew Spencer’s translation into idiomatic English renders the experiences of Hilbig’s East Germans uncomfortably and increasingly familiar to American readers witnessing the rapid decline and diminishment of their own nation and people.

Barcode: Fifteen Stories

Barcode: Fifteen Stories

Krisztina Tóth / Peter Sherwood

Jantar Publishing

Hungarian author Krisztina Tóth was born in 1967, placing the onset of her adulthood with the fall of Hungary’s communist government. The stories in Barcode occur during the cusp of the fall, both before and after, the life of the individual placed on context with the arc of her cultural history, both political and personal. Bookended by stories of death, the tales range from childhood to adulthood (mid-30s), in chronological order. The initial story (post-communism), told from the point of view of a 35-year-old woman who attends the funeral of an elderly relative, serves as an analogy of Hungary’s communist era, illustrating the confused reactions of its survivors. At the funeral, the narrator mulls over the significance of what she is witnessing and participating in:

I wonder where the boundary is, that borderline between life and no-life, between life and death, whether there is some kind of definite borderland at all. I wonder about the living and the dead, about how over the years I have learnt nothing, I’ve merely grown older, and I wonder what has happened to my self-esteem and what has taken its place, and about all the things that have not, in fact, changed and would still make it impossible for me to kiss goodbye to someone who was about to depart.

With Viktor Orbán as their prime minister, it seems that indeed most Hungarians have learned nothing from their history, only grown older.

“The Pencil Case” illustrates the communist party’s notions of how best to serve the party and nation: Harmful actions by one must be punished by all, regardless of the innocence of the person accused of performing the harmful action: Punishment outranks justice. The unnamed narrator, an elementary school girl, records the events of a very bad day: First, a boy classmate is tripped while running, falls, and rises from the ground with a bloody face. Asked by his teacher to point out the culprit, he points to the narrator, who says nothing. Later in the day, the pencil case of a girl classmate is stolen, a gift from her politically connected father, who obtained it from the West, meaning that even his humble item is of a quality outranking its domestically produced cousins. Outraged by this thievery, the teacher has the class sit in silence until the culprit confesses. The silence, the static sense of frozen time, of things remaining forever just as they are, implies a sense that progress (solving the case) is impossible without martyrdom. The teacher explains to the class,

The culprit is sitting here among us. If they admit what they have done, they can count on the others’ understanding and forgiveness. We all have our moments of weakness, but with appropriate self-discipline, self-criticism and faith in the community, such temptations can be overcome. Because we are generally aware of how we ought to behave. What the guidelines are. But on occasion even the most disciplined of students can stray. We all make mistakes, weakness as such is not unforgivable, but if we heap further lies upon the foul deed, we may forever forfeit the trust of our fellows and our teachers. Though he could have gone easy on the culprit by offering them a chance to put the pencil case on the teacher’s desk after class, he would rather give the thief the opportunity to ask for the forgiveness of the community as a whole. To exercise self-criticism in front of us all. We are none of us leaving here, said Mr Ossie, until the pencil case turns up.

The communist party, of course, did nothing but heap further lies upon its foul deeds, undermining the trust its citizens had for each other and, of course, the government itself. In Péter Nadás’s recent two-volume autobiography, Shimmering Details, he recounts instances of his parents, their family, and friends agreeing to take on false charges against themselves because the party always comes first, no matter if that means that its strongest proponents end up being executed (forget any possibility of asking the community for forgiveness—why delay the inevitable execution?). The narrator of “The Pencil Case,” ends the nerve-wracking tedium of sitting in silence by standing up to confess to a crime that the story offers no internal evidence that she committed. With this act, she shows that she had already internalized the demands of both the party and patriarchal systems in general.

In “The Castle,” the narrator is now a young teenager sent to a summer camp for female students who do well in school. Her Uncle Franci, who sells antiques, assures her that with her grades, she will do well enough to become a doctor. After a few days of camp, however, a camp run along the lines of military discipline, the narrator fantasizes only about being old to enough to be married, at which point she will no longer have to subject herself to this type of rigid nonsense dressed as character-building exercises. Once she reaches the adulthood she once yearned for, she notes that during the intervening years the hopes of her family and friends—including those who did well enough to attend camp like her—have all ended in disappointment.

Echoes of Kafka’s The Castle are probably not accidental, not just to that story but to the entire collection, in which personal hopes collide with social absurdities. As the narrator of Barcode’s final story, “Miserere,” says at its outset,

One way or another, even if it sometimes comes apart at the seams, the world is a web of often opaque laws, or of interconnections glistening like gossamer in the pale light of dawn, with the ends of each strand tied to a different corner of time.

Krisztina Tóth reconstructs the experiences of those who fall into time’s webs, with a stoic eye on the painful, translated by Peter Sherwood with understated canniness.

The Nancy Show: Celebrating the Art of Ernie Bushmiller

The Nancy Show: Celebrating the Art of Ernie Bushmiller

Peter Maresca and Brian Walker (Eds.)

Fantagraphics Sunday Press Books

The past year has seen a sudden spike in interest in Ernie Bushmiller’s long-running comic strip, Nancy: within six months of each other, first a biography of Ernie Bushmiller was published, then an anthology of long out-of-print strips. Now—through November 3 at Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum—all things Bushmiller and Nancy are being celebrated in an exhibition called “The Nancy Show: Celebrating the Art of Ernie Bushmiller.” The eponymous exhibition catalog includes many strips that have never been reprinted before, most of them from Sunday strips (including old “Fritzi Ritz” strips), which are longer than the daily strips but lack the effect of the short punch the dailies usually deliver. Since the strips are organized by topic rather than chronologically, they demonstrate that, as far as the gags went, there was no arc to Bushmiller’s career—his keen eye for visual punchlines (“the snapper” he called them)—held steady throughout the decades.

The strips and brief essays providing context for the visuals are accompanied by images of Nancy-related toys—games, dolls, cookie jars, and so forth. Nancy was never a licensing machine, so the range of things shown here are limited. Funnily enough, a doll named Nancy already existed in the toy market, so that when it came time to make dolls based on the Nancy cartoon strip, they had to be paired with a Sluggo doll and marketed as “Sluggo and Girl Friend.”

The book concludes with a succinct list of references (and excerpts from some of them), and the good news that more Nancy reprints are due out in 2025, which will mark the 100th anniversary of Ernie Bushmiller taking over the “Fritzi Ritz” strip that eventually brought us that spunky imp named Nancy and her boyfriend.

For long-standing fans of Nancy, The Nancy Show is a must. Newbies should start with Nancy and Sluggo’s Guide to Life.

Next Spring

Next Spring

Liu Yun

Sichuan Fine Arts Publishing House, ISBN 978-7-5740-0212-8

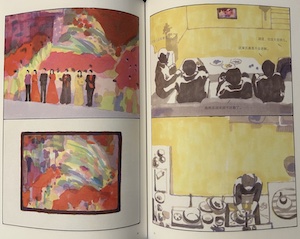

One unexpected group of beneficiaries to China’s one-child policy (which lasted from 1980-2015) were its daughters. Although long underappreciated in this rigidly hierarchical and patriarchal society, daughters born during the period of the one-child policy grew to have unprecedented importance in families that depended on the success of their children to ensure the parents’ own comfort and care in old life. Traditionally, that responsibility fell to the sons. As a result, starting in the late 1990s, daughters coming of age had opportunities previously reserved for sons, such as going to college and having a career and independent life outside of the house. Cultural / generational tensions exist now because of these changes in social roles, between the older generations who had been denied privileges and the younger who were (and are) trailblazers for young Chinese women.

In Next Spring, a young woman remembers visiting her relatives during a holiday break. She is in her last semester in college, and thus certainly looking forward to marriage, perhaps already engaged, her aunts think. They are shocked and dismayed when she tells them that she isn’t interested in marriage and begin lecturing her about its importance.

Throughout her stay during the holiday, her decision is confirmed every day to avoid or delay marriage and childbearing, based on her aunt’s life, a life of utter sacrifice to her husband and children, with no chance to leave the house, to go no further than the backyard, her escape only a climb to the roof of the house where she can be alone.

In the present day, the narrator is newly married and losing sleep over what this means for her future. Next Spring has won several awards from international animation and comics organizations based in China. One hopes that it can find a translator and publisher for an English-language edition.