I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, ephemeral, small press, comics, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired Yooper pasty pie inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If you notice titles unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at: I arrogantly recommend…

Abounding Freedom

Julien Gracq / Alice Yang

World Poetry Books

This translation of Julien Gracq’s collection of prose poetry, Abounding Freedom, is based on the third edition published in France, which included 40 poems he wrote during the two years (1941-1943) after he was released from a German prison camp (based on an incorrect diagnosis of tuberculosis), another eight written about a decade later, and another one, “Aubrac,” written in 1963, plus (new to this translated edition) excerpts from his unfinished novel, The Road.

Although an acquaintance of André Breton, who appreciated Gracq’s novels and poetry, Gracq never formally associated himself with the Surrealists, although his extravagant metaphors, and winding, unpredictable sentences suggest a kindred spirit within him.

Here is an excerpt from the page-long “Transbaikalia,” which, like almost every prose poem in this collection, teems with metaphoric imagery (Transbaikalia is a region where the far eastern borders of Russia meet the far western borders of China and Mongolia. The names Nonni, Kherlen, and Selenga are rivers in that area):

Nonni is the name I give her when she softly consoles me, hushed and tender as if behind a convent veil, it’s the stony softness of her dry hands, her little beads of sweat like a child’s, light as a drop of dew after morning’s embrace, it’s the little sister of nights pure as lilies, the little girl of innocent games, of white pillows crisp as a September morning—Kherlen is the red storms of her muscles overcome in a fever, it’s her mouth twisted by that blazing sculptural torque of iron beams after a fire, the great green waves where her jostling legs float among the sea’s fresh muscles when like a plank I sink with her through translucent strata and the blare of trembling bells that follows us to the bed of the depths—Selenga is when her dress floats like a sunlit flock of seagulls amid the morning’s empty streets, it’s in large fluttering veils, ocellated with her eyes like a peacock’s tail, it’s her liquid eyes that swim around her like dancing stars—it’s when she descends into my dreams through December’s calm chimneys, sits near my bed, and timidly takes my hand between her small fingers for the difficult trip across the night’s solemn landscapes, her eyes transparent to all the comets in the sky, open above my eyes till morning.

The book goes from strength to strength as Gracq’s increasing feel and capacity for writing these poetic sketches develops over time. In the ending to “The Uplands of Sertalejo,” the narrator is already literally on top of the world, a position that matches the exaltation of his emotions—a position, given its tone, of almost balloon-level heights. But the diction and tone modify slightly, so his euphoric visions become an unmoored craft, floating as it will down a river:

On those nights when the cold took possession of the earth, my heart reveled in its strength. I lay on the roof of the earth, palms open on the frosty grass, my eyes vanishing like an ink into the balmy depths of the night sky, the heaving of my chest breaking like a tide into the infinitely deepening ether, my gaze burning in the pure air like the pure, wandering gaze of a lookout, my heart pierced by the biting cold that was freedom from the cracked stones. At the heart of the dissolving night, all cables cut, all weights cast off, surrendering to the air and carried on water, I was a pure vessel of exchange and communion. Already half asleep, in the excess of my contentment, I squeezed Jorge’s hand in my fingers, as a sign of farewell and of a new coming.

Thanks are due to Alice Yang, whose translations uniformly render splendid results, even in seemingly knockoff lines like this tidbit from “Siesta in Dutch Flanders”: “a cyclist’s secluded trail disappears, like a finger pressing into a fur coat.”

The last work presented in Abounding, “The Road,” comes from an uncompleted novel by Gracq and suggests an intention by him to test his ability to sustain this method beyond just a few pages. One image that stands out is a long simile in which he likens the road he walks to the spreading lines on the palms of a hand, scarred by the conditions in which it was built:

the will that had made blood and sap flow into the solitudes cut from this gash [i.e., the road] had been dead for a long time—dead too were the circumstances that had guided this will; there remained an indurated, whitish scar—eaten bit by bit by the earth like a wound being healed by its flesh—whose direction was vaguely outlined still by the horizon, not a route but twilight’s muted sign to go forward, a worn lifeline that continued to sprout across the wilderness, as it might across a palm.

My Heart Has So Many Flaws: Early Poems

My Heart Has So Many Flaws: Early Poems

Robert Walser / Kristofor Minta

Sublunary Editions

Robert Walser (1878-1956), the 20th-century Swiss writer best known—if he’s known at all—as the guy who committed himself to an asylum with the words, “I am not here to write but to be mad,” and as the guy who (in a different asylum) wrote stories and even at least one novel (all discovered after his death) in a tiny microscript small enough fit an entire novel on a single legal-sized sheet of paper (526 pages of microscript have been recovered so far). For Anglophone readers such as myself who look forward to every new batch of translated works to appear in English, Walser’s fiction and poetry comes in frustratingly small drips and drabs of 150 pages or so at a time, every other year or so, whereas his actual output amounted to umpteen thousands of pages. Most works translated into English to date have focused on his fiction, with a smaller number devoted to his dramatic works, and an even smaller amount on his poetry, which provide a new seam for translations in an already rich lode.

Kristofor Minta has dared to translate some of Walser’s earliest extant works, poems from the beginning of his career before his writing matured into the attitude that marked his works from after WWI until his death. Those works feature narrators whose self-presentation is of a person I imagine smiling through gritted teeth, a man whose front is that of an eager and optimistic person, but one prone to destroying the very opportunities he sought out himself by suddenly feigning insult by others to his dignity and stomping off in high dudgeon. The resulting tone—cheerful yet distraught—and the emotional balancing act it implies requires a subtlety in word choice difficult to achieve. (For Walser’s prose works, my personal standards are reflected in Christopher Middleton’s and Susan Bernofsky’s translations, which successfully capture the narrators’ anxieties and neuroses, which taint and undercut the simultaneous expressions of cheerfulness.)

Minta, in his excellent Afterword to My Heart, argues—convincingly, I think—that it’s in Walser’s earlier works—these poems, in particular—that the real Walser lies closer to the surface and is admitted to: his fear of shame and embarrassment, his unending anxieties and nervousness, frequent bouts of crying, his need for the solace of walks and nature to distract him from his profound alienation from those around him—the same people he wishes desperately would accept him. Minta describes Walser’s rhetorical moves as “hiding,” in which his prose provides a forum for Walser to play hide-and-seek with the audience, hiding his fears, anxieties, and depression—just when the prose might be at its most revealing and insightful about human behavior (Walser’s behavior, at any rate)—he hides behind what I sense is a taught rictus of a smile topped by piercing eyes (that never look directly into your own) outlined in red. Still, the result of that emotional paralysis and catastrophe—how Walser’s narrators describe and apologize for their reactions—shape his narrators as engaging mysteries we are willing to follow wherever they go.

But before he developed into an enigma, he wrote these poems. Most first appeared in newspapers, and for a few years he was able to make a modest living from having his poems, stories, essays, and sketches published in papers. He apprenticed as a poet from 1897 to 1919 as a writer of verse heavily influenced by German lieder, or songs. Because they were based on a popular song format, they rhymed. Sing-songy rhyming is anathema to most contemporary readers of poetry, and hence the reason, Minta asserts, for translators dismissing Walser’s early poetry. Because Minta is more interested in translating Walser’s poems for their meaning than their aurality, he eschews attempts to force rhymes in English. Oddly enough, while he defends Walser’s lieder-influenced poetry against Modernist sensibilities appalled by rhyme schemes, Minta’s translations end up sounding Modernist just by dint of lacking rhymes. Without the rhymes, Walser’s diction no longer seems simplistic and repetitive—as a song genre might imply—but as a harbinger of writers like Gertrude Stein, whose repetitive monosyllabic prose nobody ever accused of being simplistic. Repetition by Stein and the early poetry of Walser works to affect nuance of connotation, suggest understatement, and, in the case of Walser, ache and yearning.

Walser’s “Always Onward” anticipates Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” and their theme of pushing on, despite the need for respite and the narrators’ bedazzlement by nature:

I wanted to linger.

I pushed on again,

past black trees,

yet promptly wanted

to stop awhile under black trees.

I pushed on again,

past green meadows,

yet I only wanted to linger

in green meadows.

I pushed on again

past shabby cottages.

By one of those cottages,

though, I’d like to have lingered,

to contemplate its poverty

and how its smoke rises

into the sky, the sky—

I’d like to stop now

a good long while.

I said this and laughed.

The green of the meadows laughed.

The smoke rose, smokily smiling.

I pushed on again.

The idea of pushing on suggest perseverance and consistency to duty. But in “The Silence,” the notion of pushing on takes on another cast, one in which duty toward others can also be seen as fleeing from the harpies of one’s own mind:

How glad I would be

if only I could rest

quietly somewhere.

Satisfaction,

like a warm robe,

would grant me inner silence.

How I’d love

if somehow

I could find solace in it.

What’s certain:

all strife would

find an end there.

As one might expect from a novice poet, not every effort meets with success, and some poems betray the hand of a young man with overly romantic notions of the world. Apart from those infelicities, many of these poems bare the seeds of what was to become the Walserian style, and we fans of Walser owe a round of thanks to Minta for his fine translations of Walser’s initial steps into literature.

Elixir

Elixir

Lewis Warsh

Ugly Duckling Presse

Elixir is the last collection of poetry from the co-founder of Angel Hair and United Artists Books, Lewis Warsh, who died in 2020. Through poetry, Warsh shapes colloquial speech, with its commonly-used phrases, into poetic observations of everyday life: “lying through your teeth,” “ships in the night,” “split the difference,” “it occurs to me,” “hold on tight,” and other mundanities lacking precision and originality in naming and describing actions. Warsh’s ability to poeticize trite phrases is akin to transforming a black velvet painting into an artwork that transcends the debased medium it was created in.

Written usually in stanzas of semi-regular form and blank verse, often using enjambment to change a sentence’s direction, meaning, and/or nuance, the poems startling and engage with their unpredictable semantic and syntactic flow. From section 13 of “On the Western Front”:

Cold brisket waits for no one.

It comes with a baguette.

She leapt to her feet

as if someone had summoned her

from the dead. The feeling

is reciprocal.

I pull up my fly

in mixed company.

Full moon at noon.

Three songs for a quarter.

Put it in writing, just in case

I forget. A couple of Sprites

on tap? My name is Rene.

I’ll take your order.

The tone in much of the poetry is playful; its attitude invites readers to participate in that playfulness.

Hereafter

Hereafter

Alan Felsenthal

The Song Cave

A meditative series of poems alternately concerning the death of a friend and nature as a symbol of hope and constancy. Composed in spare lines of 3 and 4 feet in the lyric mode, a page or two long, many written as a single stanza. Here is “The Hawk at Washington Square Park,” with its almost Eastern consolation for the “bitterness” of life while exemplifying its cure:

Set on a wire, on a breezeless

day, his frame was

a figurine that stared at us.

People, eyes on each other, pass.

The majestic sentinel sits

slightly above our bitterness,

his body its own crutch. He is

proving the true nature of his

greatness by being ignored. As

if saying, impassively, be noiseless,

unseen, not behind or under us—

you belong to your times—

but above, commit to spirit, yours.

And then a gentle wind comes.

Sparely punctuated, often using internal rhymes and slant rhymes to cohere the images, Hereafter provides gentle explorations of how to live, the metaphysics of a good existence.

Valley of the Many-Colored Grasses

Valley of the Many-Colored Grasses

Ronald Johnson

The Song Cave

Kansas-born American poet Ronald Johnson (1935-1998) wrote free verse influenced by, for two, Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson, with a concern for nature and humanity shared with them and the shared history of place and life force that unite them. Valley of the Many-Colored Grasses collects two early and long out-of-print books, A Line of Poetry, A Row of Trees and The Different Musics, each from the 1960s. In the latter collection, Johnson makes explicit Whitman’s influence on him in the sequence of poems called “Letters to Walt Whitman,” in which Johnson enters a dialogue with the poet, beginning with Whitman’s own words in italics:

The press of my foot to the earth

springs a hundred affections,

They scorn the best I can do to relate them. . .

(The moth and the fish-eggs are in their place, The bright

suns I see and the dark suns I cannot see

are in their place. . .)

I see a galaxy of gnats,

close-knit, & whirling through the air,

apparently for the pure joy of the circle, the jocund

inter-twinement.

And through this seethe,

I see the trees,

the blue accumulations of the air

beyond,

perceived

as through a sieve—

& all, through other, & invisible, convolutions:

those galaxies in a head

close-packed & wheeling

I am involved with the palpable

as well

as the impalpable,

where I walk, mysteries catch at my heels

& cling

like cockle-burrs.

My affinities are infinite, & from moment to moment

I propagate new symmetries, new

hinges, new edges.

The “galaxy of gnats” doubles as a reference to William Blake’s universe in a grain of sand—and as acknowledgement of Blake as progenitor to himself, Johnson, and Whitman—while its open-armed incantation of nature seems to, as with Whitman, simultaneously evoke and create its multifarious aspects by naming, witnessing, and participating in its joys and creations, the poem’s internal cohesion brought about by internal rhymes and assonance.

“The Different Musics,” dedicated to fellow poet Robert Duncan, suggests a duet of sorts between two sensibilities (or two aspects of a single personality) structured, first, as separate stanzas, allowing each voice and sensibility to present itself; second, as two different statements spoken simultaneously but not synchronously; and third, united in word and pace. The two stanzas by the first speaker of the first part are set flush left, the two of the second flush right. In the second part, the lines flush left and down the page form one set of stanzas, on the right another set by the second speaker.

In the third section of “The Different Musics,” the text is centered like a scroll unfurling at the beginning of a film, exuberantly announcing the spectacle to be shown:

And night comes opening its arms like smokes to enfold us:

THE DANCERS!

Where their feet touch the earth

an encircling of plume, diaphanous featherings.

THE DANCERS!

And the dark came

—a ring of beasts, with smoldering eyes—

to the edges of a grove. .

A spreading effulgence!

A resplendent ‘hood’ of light!

A choric turbulence, to which the worlds keep time.

There is genuine joy throughout these poems. Thanks to the folks at The Song Cave for returning that joy to the printed book.

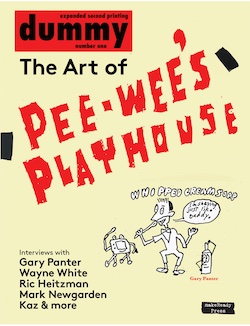

Dummy is a new quarterly zine written by John Kelly, who has covered comics and creativity for over 30 years. Devoted to, as its subtitle suggests, “comics and arts,” each issue of Dummy focuses on a specific topic. For the initial issue, the topic is “The Art of Pee-wee’s Playhouse,” which translates into lots of artwork from its initial theatrical run, then TV series, then product spinoffs.

Paul Reubens, aka Pee-wee Herman, hired artist Gary Panter as his set designer, and Panter hired additional artists to help him take on all the work designing furniture, puppets, costumes, characters, toys, stickers, and much more. Panter hired fellow artists who appeared alongside him in art spiegelman and François Mouly’s RAW comics, Kaz and Mark Newgarden, as well as Wayne White and Ric Heitzman. Reuben’s implicitly trusted Panter’s visual taste, so anything Panter approved of, Reuben was likely to, as well.

In addition to the artwork are anecdotes from the artists regarding their contributions and working with Reubens. The consensus is that Reubens could have made more money from product endorsements, but stayed away from things or themes he didn’t think were good for kid. Like sugared cereal:

“So my cereal was going to be called Pee-wee Chow,” Reubens said in a 2011 episode of NPR’s Wait Wait… Don’t Tell Me! radio program. “I actually talked the Purina Company into doing my cereal. And it was going to be the first time that they ever allowed the checkerboard to be put on something other than pet food. . . And the commercial for it was going to be a mom, a 1950s mom pouring a bowl and putting it on the floor and kids, like, crawling up [like dogs] and eating it. . . But it turned out, kids didn’t like it. They wanted a sweeter cereal.”

Issue #2 should be out soon. Twice as big as the first issue, its follow-up will focus on the Air Pirates Funnies, originally published in the early ‘70s, specializing in Disney parodies that were quickly squashed by Disney’s legal team, and their cartoon cousin, Mickey Rat. Number 3 will focus on little-known Nancy-related ephemera, and a future issue may focus on ephemera from the Church of “Bob” Dobbs.

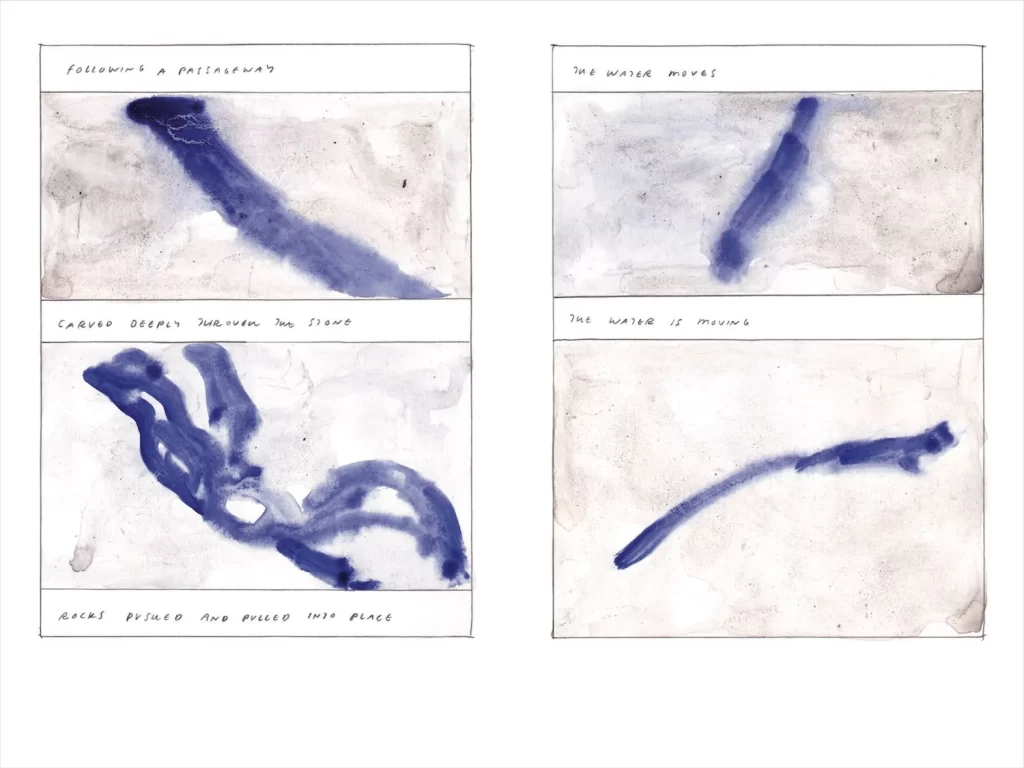

Spiral & Other Stories

Spiral & Other Stories

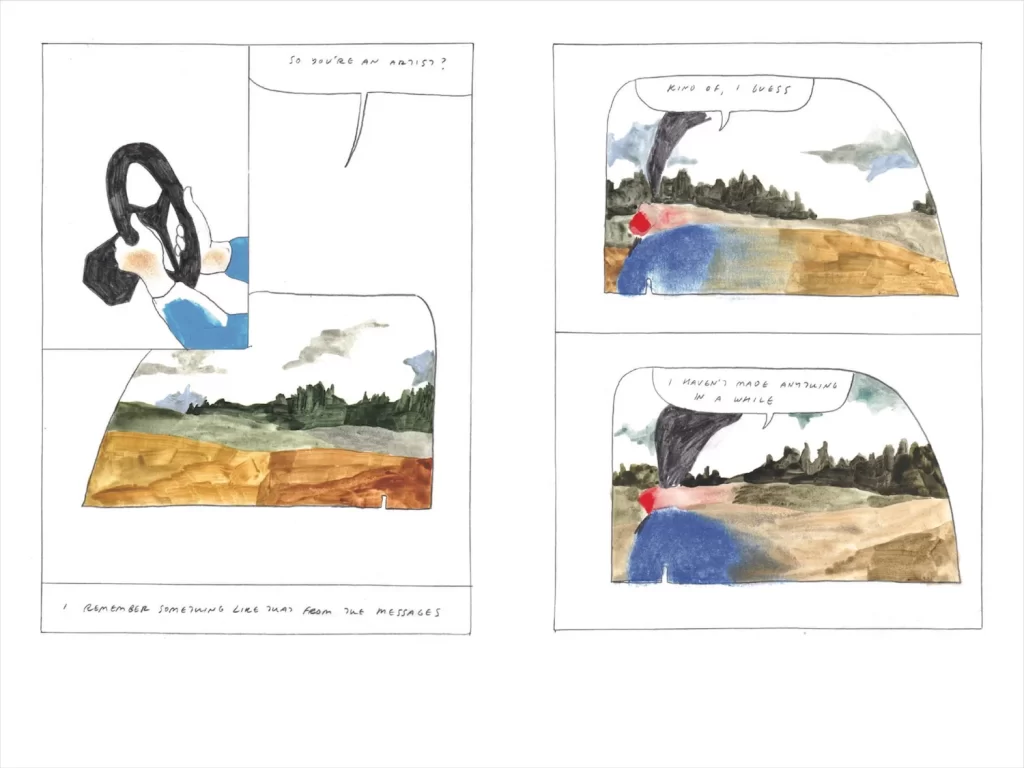

Aidan Koch

NYR Comics

Offering vignettes about history, place, companionship, and love, Aidan Koch uses a spare, elliptical style of verbal and visual narration. Aiming for a haiku-like concision in words that frame Koch’s pastel watercolors, gouache, and pencils, her thin, smooth lines remind me of those drawn by Dash Shaw and CF (Christopher Forgues, soon also to be published by NYR Comics). Any number of her panels could double as abstract paintings; it’s the narration that tells us how to see the streams of colors, with just enough hint from the words and images together to fill in the rest. The aura of place, of nature, and of deep time lend the title story, Spiril, a Zen-like harmony of nondirected, non-purposeful action that is, therefore, natural and essential. In describing and illustrating the formation of two rivers over time that eventually meet, Koch writes, “The water never thought about what would happen, how it would transform. . . How it would lose the shape of its body.”

An excellent collection.

As a sidebar, one of the stories here, “Man Made Lake,” was originally published by the Lithuanian comic book publishers of the kuš! and mini-kuš! series, which I’ve reviewed here: (3rd review down).

The Willows

The Willows

Ryan Thorpe

Aethon Books

The Willows is the first volume in a YA fantasy trilogy by newcomer Ryan Thorpe. With enough action and interwoven storylines to keep this coming-of-age saga moving at a good, engaging clip, the story begins—as do all stories about good versus evil—when a major figure says to the powers of good, “I shall not serve.” The powers of good in Silverwood Forest are represented by Barnabas, the warden of the magical forest, whose main task is to keep the powers of evil at bay in the forest. Widow Jones is a witch whose amassing of evil to counteract Barnabas must be purged from the forest on a cyclical basis. Her purging consists of being set on fire. From her ashes, she slowly arises again, and again begins developing her magical prowess.

This cycle through, however, she refuses the burning so she can continue to amass her magical powers unabated and thereby come to outpower Barnabas so she can rule the forest herself. Although Barnabas is aging, he is training his son, Isaac, to take his place. Isaac, a teenager of high-school age, isn’t terribly interested in magic or managing the forest. His study of magic spells has been half-hearted, and he hasn’t committed anything to memory. What the lad needs, Barnabas realizes, is a test of his abilities, a rite of passage that will push Isaac to the edge of his self-confidence and anomie attitude toward his future career, best achieved by kicking Isaac out of the house.

Enter the Willows. The Willows are a group of teens—Peter, Dionysus, Mae, Ashley, and Stephen—who live in Lutra, the nonmagical town on the other side of the forest. For the citizens of Lutra, Silverwood is a place more talked about than visited, since it is a place of—at best—odd occurrences. They’re good kids, the kind who don’t seem to fit in with others, but not for any discernable reason. (Except for Dionysus, who is a walking dictionary and the group’s logician.) Like most teens, their self-assurance is iffy, and they are routinely set upon by a group of bullies. It is during one of these after-school dust ups that Isaac arrives, which he quickly sees needs to be nipped. The bullies, who are fairly dim after all, receive their first lesson in social etiquette from Isaac and run away, tails between trembling legs. Isaac is then made an honorary member of the Willows.

Knowing that Isaac is away from his father’s protection, Widow Jones and her assistant, the nattily dressed Lawrence, attempt to capture and kill Isaac and his teenage posse. But Jones’s plans don’t go as smoothly as she hopes: Isaac’s magic skills are beginning to kick in and the other Willows have each been endowed with a modicum of magical abilities, thanks to Barnabas, who knows they will need protection if they insist on helping Isaac through his rite of passage. Nonetheless, just what they can do to protect themselves is unknown territory to all of them (the whole point of a rite of passage), and the variety of spells and battles (against bizarre creatures) they are confronted with keep pulling the rug out from them: Nothing is certain, let alone the assumption that they will win their battles, an uncertainty that increases substantially toward the end of this first book with the appearance of the Dark Warden. His life had been spared by Barnabas some years before, shackling him in prison for life, instead. But now the Dark Warden has managed to escape, setting his eyes on gaining control of the forest.

However, in addition to his opponent, the good Barnabas, is the evil Widow Jones, who refuses to defer to the Dark Warden, creating a double of herself to attend his command meeting of evil forest entities to act as a distraction while she hones her own powers and rounds up allies in hiding.

After the climactic battle that ends the first volume, between the Dark Warden and Barnabas, with help from Isaac and the Willows with the serious injury of one member of the group, the Willows vow revenge, their hearts filled with sorry and rage. But the vary hatred that now motivates them will be their greatest weakness: The Dark Warden feeds on hatred and knows how to turn it against those who have it.

The climactic battle between the Dark Warden and Barnabas that ends the first volume results in the serious injury of a member of the group. The Willows vow revenge, their hearts filled with sorrow and rage. But the vary hatred that now motivates them will be their greatest weakness: The Dark Warden feeds on hatred and knows how to turn it against those who have it.

The Willows have proven to themselves and each other their bravery, intelligence, and confidence. Now can they master their emotions to defeat the hatred eating at their conscience?

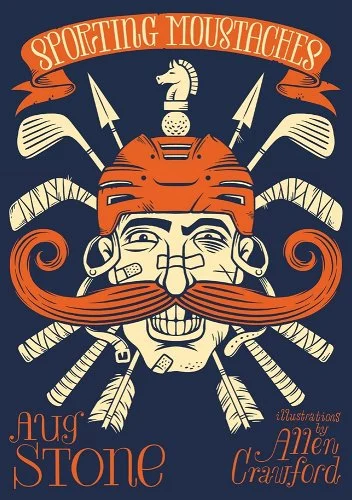

Sporting Moustaches

Sporting Moustaches

Aug Stone with illustrations by Allen Crawford

Sagging Meniscus

Sporting Moustaches is Aug Stone’s second book, his first collection of short stories following almost immediately on the heels of The Ballad of Buttery Cake Ass, his novel about the haphazard fortunes of a haphazard band (reviewed here, 13th book down. Sporting collect a baker’s dozen tall tales (think urban legends) illustrating the dramatic role moustaches have played in the history of various sports. No goatees, mutton chops, or beards, just pure ‘stachety.

Wrapped around the hand of a hockey stick, a player’s chest-length moustache gives him extra stick-handling prowess. Waxed into wide curls, a baseball player’s moustache increases his confidence and RBI with every inch it grows. There are chess matches and tugs of war (in which moustaches are tied to a rope pulled by the competitors’ faces), badminton, archery, and more. There is love and heartache, vengeance, nefarious plotting, and an awful lot of competitions whose rules say nothing about mustachioed assistance. Stone hasn’t lost his fondness for puns and silly names based on the names of famous people, as shown in Ballad, and his stories’ taut storylines keep the action and dialogue more focused than the relatively baggier Ballad, indicating a quickly developing talent.

The Answer to Lord Chandos

The Answer to Lord Chandos

Pascal Quignard / Stéphanie Boulard and Timothy Lavenz

Wakefield Press

Hugo von Hofmannsthal wrote “The Letter” in 1902, a story written in epistolary form by one Lord Chandos to Francis Bacon (1561-1626). Dated 1603, the letter comes as a belated response by Chandos to a letter from Bacon two years earlier. Chandos, we come to learn, was an intellectual prodigy who, by age 19, was publishing important philosophical treatises that caught the admiration of such world-renown thinkers as Francis Bacon, who gave us the scientific method. Chandos’s publications and achievements followed in quick succession, only to suddenly cease. Bacon, concerned about the cause of Chandos’s silence, asks Chandos about what has happened. The seriousness of the silence is indicated by the time it takes Chandos to respond, his conscience finally overruling whatever other urges have held him back.

Chandos tells Bacon that several years ago, he suddenly found himself unable to speak without making himself sick. He noticed of himself that his comments were founded on abstractions, a black and white sense of morality, and a conviction in beliefs upon which there was no factual basis. The principles he once held dear, learned from and espoused by Seneca and Cicero, were self-referential platitudes: they were true because each member of the group said they were true. Instead of looking forward to the deep insights his observations formerly brought him, he now finds himself engaged by the prosaic:

A watering can, a harrow left in a field, a dog in the sun, a shabby churchyard, a cripple, a small farmhouse—any of these can become the vessel of my revelation. Any of these things and the thousand similar ones past which the eye ordinarily glides with natural indifference can at any moment—which I am completely unable to elicit—suddenly take on for me a sublime and moving aura which words seem too weak to describe.

(Joel Rotenberg’s translation.) And here I think of William Carlos Williams’s “The Red Wheelbarrow,” first published in 1923, and its contemplative gaze at a rain-washed wheelbarrow. Hofmannsthal in 1902 seems to be anticipating a change in Western cultural mood that snapped into place after the atrocities of WWI, indicated by its rejection of grandiose ideals. Think of Hemingway’s characters casting flies in Spanish streams compared with, say, the social-climbing protagonists of Eliot’s Middlemarch.

Behind everything, Chandos realizes, is death. And death marks the futility of “progress” and “understanding.” His realization has made him both more emotionally distant from and empathetically closer to all entities that live, hurt, and die: “Forgive this description, but do not think it was pity that I felt. . . It was much more and much less than pity—a vast empathy, a streaming across into those creatures, or a feeling that a flux of life and death, of dreaming and waking, had streamed into them for an instant (from where?).”

Chandos is aghast at the impermanence around him—but it is an impermanence shot through with an eternal essence whose paradox he finds difficult to articulate. (In short, it seems that Chandos needs an infusion of Buddhism to help him sort things out.) “I can no more express in rational language [my emphasis] what made up this harmony permeating me and the entire world, or how it made itself perceptible to me, than I can describe with any precision the inner movements of my intestines or the engorgement of my veins.” Instead, he finds that “my eye is lingering for a long time on the ugly puppies or the cats slinking lithely between flowerpots, and searching among all the shabby and crude objects of a rough life for that one whose unprepossessing form, whose unnoticed presence lying on or leaning against something, whose mute existence can become the source of that mysterious, wordless, infinite rapture.”

And because of his inability to express himself with rational exactitude, he has chosen silence.

The assertion that limitations of language and its inability to be infinitely calibrated to specific ideas and moods lead many 20th-century writers and thinkers of a philosophical bent to see the entire enterprise of communication as, well maybe not a hoax, but as exercises in frustration. Certainly, the French deconstructionists did what they could to destabilize notions of meaning and intention. “The Chandos Letter” anticipates that anxiety and articulates the reasons behind it.

Some writers—such as Pascal Quinard in the case of the book under review, The Answer to Lord Chandos—find suffocating the supposition that silence is the only proper answer to the paradox Chandos outlines in his letter.

Beginning with sketches from the lives of Emily Brönte and George Frideric Handel and ending with one on one of Bluebeard’s wives, these bookends provide oblique commentary on the letter making up the core of Quignard’s literary-philosophical response to Chandos in the guise of Francis Bacon:

I think that in beauty itself there is something cowardly that hides, that doesn’t want to aggress, that retreats from the real, and maybe that alone was enough to corrupt your thought. You [Chandos] renounce poetry. How wrong you are! You are a great poet. Your conception of silence comes directly from Epicurus. This “illusion of silence” upstream of the acquisition of language, and even the idea of “language at rest” with regard to an artifice that is, however, nothing like an animal that can experience fatigue, are by no means convincing or strong.

For Quinard’s Bacon, silence as response is a form of false consciousness. “But never, do you hear, never will you escape the language in whose sound your mother cradled you to the point that she was able to immerge you in it permanently. Never. Even in the other world your soul will not be free of it.” The only true silence is the pre-linguistic silence of the womb; to want that silence is to regress, not progress past. And there is no progressing past language. Language, grammar, syntax, rhetoric—all tools whose refinement of use depends on the person who could communicate. The existence of time allows for refinement to occur.

You must adore, in the acquired language, the failure of acquisition, which ceaselessly limits everything and yet never restricts language. You must fight with this failure to speak the lost world. Language is the with of our soul. It is a door always. And aways it is a door that opens to whoever pushes it.

Bacon’s exuberant response to Chandos’s withdrawn nature is of accord with the scientific method, which is, after all, an eternal process of testing, improving, testing again, improving more—a process that, while committed to betterment, admits to the project’s asymptotic nature: The goal will never be achieved. But—

Your letter is that very first language which draws attention to the accursed share of ordinary things and [their] inconsolable sobs. . . Your language suddenly becomes a poem. Contrary to your arid, dried up, confiscated soul, it has become liquid, flowing, lively once more. . . Silence is what the language we have learned invents as its opposite so that language will emerge.

Fear and Trembling and The Sickness unto Death

Fear and Trembling and The Sickness unto Death

Søren Kierkegaard / Bruce H. Kirmmse

Princeton University Press

The recent publication of two new translations of works by Kierkegaard encouraged me to finally satisfy my curiosity and read him. I’m neither a theologian nor philosopher by training, as was Kierkegaard, just a layman interested in hearing his discussions. Over the decades, I’ve read enough of his aphorisms—deployed by other writers for their incise irony—to sense in him a kindred (exasperated) spirit, despite my dogmatic agnosticism versus his Lutheran Christianity.

Bruce H. Kirmmse is an ideal translator of and commentator on Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling and The Sickness unto Death. As a professor emeritus at Connecticut College and a world-renown scholar of Søren Kierkegaard, Kirmmse comes to the task with an ideal set of skills: fluent in Danish and the technical languages of philosophy and theology. As to whether a general reader needs to be a Christian or, more narrowly, a Lutheran to appreciate Kierkegaard’s arguments, I would argue No, based on the sheer quality and insightfulness of the issues he examines in Fear and Sickness, namely, what faith consists of and despair as its lack.

In Fear and Trembling, Kierkegaard chides his fellow church-going Danes for their sense of faith. For them, he argues, what they call faith is actually a transactional relationship. In such a relationship, people believe that if they follow the Bible’s rules, they will receive eternal life, whether they believed in God or not or meant what they said. For Kierkegaard, this is sheer nonsense. Instead, a true act of faith pits two values against each other, each admirable on its own but together forming—not the disaster a reasonable person might otherwise predict—a transcendent moment in which the elements of the paradox can exist in harmony with each other.

I think this is where non-believers are tempted to drop Kierkegaard. Whereas contradiction is inconsistent with logic, it is essential to Kierkegaard’s metaphysics. Fear and Trembling takes as its core paradoxical situation God’s commandment to Abraham to sacrifice his son, Isaac. As a father, Kierkegaard argues, Abraham’s greatest duty is to make his son’s life the best, most fulfilled it can be. As God’s subject, Abraham’s greatest duty is to follow his every commandment. Both acts—to count as acts of true faith—must be performed instinctually, without question or hesitation: “faith begins where thinking stops.” If we can make sense of Abraham’s actions—whether we agree with them or not, then we are not dealing with faith but with rationalization. Kierkegaard is first to insist that Abraham’s unflinching preparation to sacrifice Isaac has not a single rational element to it. Of course Abraham wasn’t going to tell his wife about it! Of course the neighbors didn’t know! Etc.

While Kierkegaard spends four chapters describing the problems Abraham’s actions raise, he also argues that, for Abraham’s actions to fulfill God’s commands, individual morals have, for a moment, transcended over universal ethics (which include the ethics that apply to all). Between God’s commandment to Abraham to sacrifice Isaac and His command to stop the sacrifice, neither individual morality or universal ethics obtain, nor is one superior to the other.

While he prepares to sacrifice Isaac, Abraham exists in a suspended state in which the spiritual is more important than the universal. It has nothing to do with heroism, just as—to use Kierkegaard’s example—Mary’s pregnancy with Jesus had nothing to do with heroism: God placed her in a position she accepted, and her only concern was with pleasing God, not explaining rationally to other women, for instance, how she became pregnant and with whom she became pregnant.

Part of the paradox of Abraham’s faith is that he may love Isaac more than God (loving his son more than anything is part of his duties as a father) but to enter heaven, one must love God above all others. God’s requested sacrifice will demonstrate Abraham’s superior love for God, not signal that Abraham “hates” his son. (The “hates” here taken from “Whoever does not love his mother, father, [etc.] more than me. . .”)

Kierkegaard openly doubts whether he has within himself that level of faith.

In The Sickness unto Death, Kierkegaard looks at the relationship of oneself to oneself as it relates to the state of despair. He notes that when we think to ourselves, there is that voice in our head we listen to and engage with. If we forget to acknowledge the third portion of ourselves, we are in a state of despair, which is a sin. The third portion is the God who created us and wants only the best for us (which may have nothing to do with material status). Thus, we must always keep in mind that a participant in talks with ourselves should be God. In a surprising twist, Kierkegaard asserts that the opposite of sin is not virtue—nobody is perfect. The opposite of sin is faith, which recognizes our ongoing struggles to act and think with love and that we have that part of us created by a God we can always turn to.

As with Fear and Trembling, the faith required to believe that the God-component of our soul is always there has nothing to do with rational behavior justified by rational arguments.

But this is precisely the way in which Christianity is spoken of—by believing priests: either they “defend” Christianity, or they transpose it into “reason,” to the extent that they do not also dabble in “comprehending” it speculatively. This is what is called preaching, and in Christendom it is even regarded as something great that there is preaching of this sort and that someone then listens to it. And it is precisely for this reason (this is the proof of it) that Christendom is so far from being what it says it is, that the lives of most people, understood in the Christian sense, are indeed too spiritless even to be called sin in the strictly Christian sense.

Acts of explaining Biblical texts in scientific jargon to give faith a foothold on rational behavior entirely miss the point of what faith is. Perhaps a material world requires rational systems of logic, but under what basis can it be assumed that metaphysical conditions must follow the rules of physical conditions? Kierkegaard’s is a theology that puts absurdity front and center.

[B]ut from a Christian point of view (this must be believed, for it is of course a paradox that no human being can comprehend) sin is a position which develops an increasingly positive continuity out of itself.

The more one distances one’s soul from its divine source via rational discourse, the more sin one perpetuates, wallowing in the joys of material logic, a state of delusion known as despair.