I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, ephemeral, small press, comics, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, ephemeral, small press, comics, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If you notice titles unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at: I arrogantly recommend…

In the Glittering Maw: Selected Poems

In the Glittering Maw: Selected Poems

Joyce Mansour / C. Francis Fisher

World Poetry Books

Joyce Mansour was born in 1928 in England, the daughter of a Syrian-Jewish couple who soon moved to Cairo, where she grew up. Her second husband was an older banker who spoke only French, and together they circulated among Cairo’s literary salons. (Her first husband died of cancer only six months after they wed, when Mansour was 19.) The installation of Nasser as leader of Egypt, eliminating its monarchial system of government, put the couple at political odds with the new government. They thus moved to Paris where she discovered Surrealism and the Surrealist André Breton discovered her—and promoted her work.

“The Breastplate” starts the collection off rudely with a poem told from a bomb’s point of view, from flight to drop, sadistically enjoying the lives it destroys and havoc it wreaks—a poem more contemporary in its descriptions than one would wish:

When war begins to rain on the swell and on the beaches

I will go to meet it with my face

Coiffed with a heavy sob

I will lie flat on my stomach

Atop the wing of a bomber

And I will wait

When the cement begins burning the sidewalks

I will follow the bombs’ routes amidst the grimaces of the crowd

I will stick to the rubble

Like a tuft of hair on a nude

My eyes will escort the stretched contours of desolation

The dead blazing with sun and blood

Will be silent by my side

Nurses gloved in skin

Will wade in the soft liquid of human life. . .

Mansour also has her erotic turns, too. Although the following example, “Friends’ Eyes,” is less graphic than her other erotic poems, it also mingles elements of wistful and sentimental nostalgia for a lost lover:

I was looking for your heart beneath a pile of debris

A strange perfume shaggy and prudent

Was frisking by my side without putting out its gray cigar

Wared-up leftovers passed under my nose

Ligules of llamas feathers of lilac

Tentacles that bind more tightly than disease

Inedible memories of naked engravings with full hips

Floors of the past eaten away by dementia

Others more conformist painted with rice powder

Surrounded their furniture with pomp and ceremonial lace

I was looking for your heart under a pile of gray papers

But the perfume of your love put out its cigar on the carpet

And I was left alone with the ashes of a clever joke

In addition to their striking imagery, Mansour’s enjammed lines often change the tone, direction, and/or meaning of the preceding text. That and the poems’ lack of punctuation encourage slow, multiple readings for their fullness to unfurl.

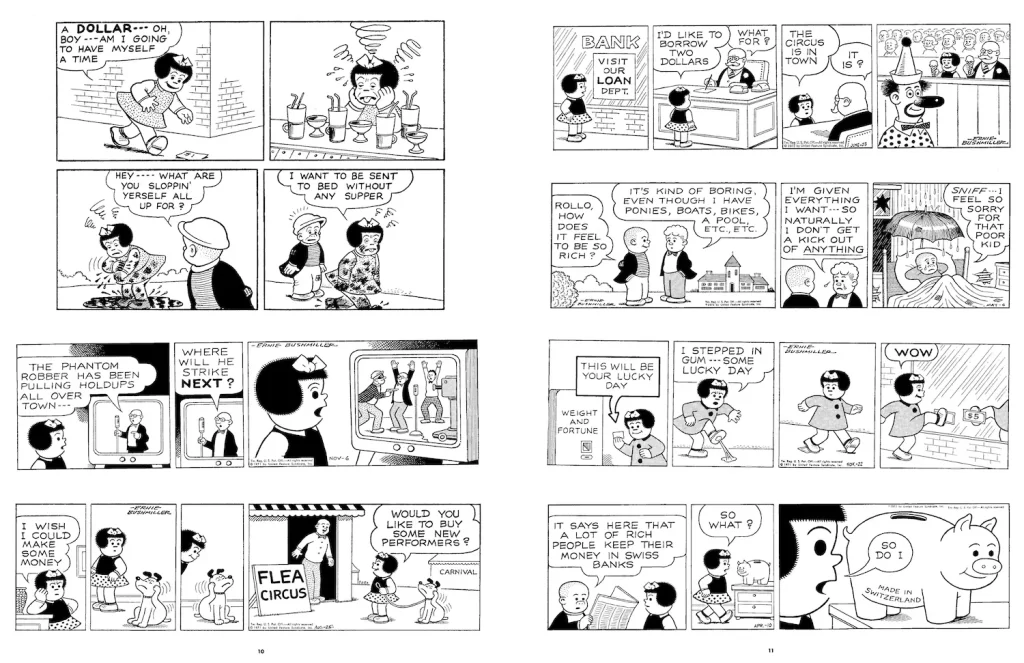

Nancy and Sluggo’s Guide to Life: Comics about Money, Food, and Other Essentials

Nancy and Sluggo’s Guide to Life: Comics about Money, Food, and Other Essentials

Ernie Bushmiller

NYRComics

The strips in this collection of Nancy cartoons have been culled by comix publisher Denis Kitchen from his five books of Nancy strips, published in the late 1980s. Included here, too, are strips that have never been reprinted before, all on the topic of money (?!). Now that Fantagraphics’ reprint series is moribund (having stopped at Volume 3, which takes us to 1951, when Bushmiller’s career still had decades to go), it’s great to have new (for many of us) Nancy strips in book form and cheering to see that Bushmiller’s knack for a good gag didn’t fade. Denis Kitchen delivers on the request made to him by NYRComics to produce a “best of” volume, which serves well both Nancy neophytes and old fans—the visual gags (which play with the format of newspaper strips), the puns, and of course Nancy’s eternal spunk and DIY attitude—which probably helps explain Kitchen’s observation in his intro that many young women are now discovering and falling in love with Nancy. Most of the strips are from the ‘60s and ‘70s, and none (I think) repeat any in the Fantagraphics reprint series. Pairs well with Bill Griffith’s new biography of Bushmiller, Three Rocks

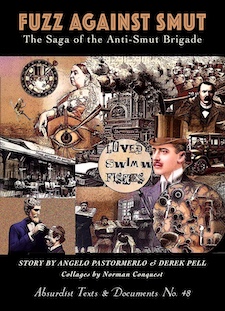

Fuzz Against Smut: The Saga of the Anti-Smut Brigade

Fuzz Against Smut: The Saga of the Anti-Smut Brigade

Angelo Pastormerlo & Derek Pell with collages by Norman Conquest

Black Scat Books

A short work of satire and collage about a Sherlock Holmes-like detective, Sir Reginald Fuzz (“foremost moralist, expert on the perils of pornography, and chief of the Anti-Smut Brigade”), and his clueless sidekick, Dr John Twatson. Called out of retirement by Scotland Yard to deal with the perfusion of pornography and pornographic paraphernalia circulating throughout London, Fuzz sets out to determine the identity of the perfidious scoundrel who attached an anonymous note to a large bundle of pornography dropped off at a bookstore, threatening death to anybody who tries to stop the porn’s distribution. After doing research on the street and in businesses of questionable repute and attempting to decode the letter (breaking it into smaller passages he tests for the anagrams they produce), Fuzz determines the source of the pornography to be his old nemesis, Maurice Dildeaux. Fuzz heads to Dildeaux’s home base, France—enemy territory, whose citizens themselves gleefully accept and partake of the vice. Will Fuzz survive the encounter? Amply illustrated with collages based on 19th-century illustrations, simply for reasons of educating naïve readers to help them know porn when they see it and help them steer clear of moral turpitude.

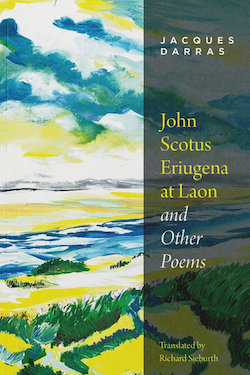

John Scotus Eriugena at Laon and Other Poems

John Scotus Eriugena at Laon and Other Poems

Jacques Darras / Richard Sieburth

World Poetry Books

John Scotus Eriugena at Laon collects excerpts from French poet Jacques Darras’s 8-volume, 2,700-page poem called La Maye, which show influences on Darras ranging from Augustine to Wordsworth, including poets Darras has translated, such as Basil Bunting and Ted Hughes. Spiritually, the poetics bias toward the paganism of northern British Isles and less so the Christianity imported there and throughout France from Augustine’s North Africa. Topically, the Darras’s works present philosophical observations of nature via poetry, as in “Beeches,” from early in the book:

this is no shadow that lies astride the beech trees

beeches being so tall so proximate

to the sky as to eliminate every fringe of light

from their environment yet filtering it through

the canopy at the convergence of their branches

on high providing a unanimous solar

version of the day on the reverse side

of the leaves whose transparency presumes

a yellow sky, the light decomposing

leaving the marks of its origins in the stars

on the leaf-strewn selvage of the soil

while the stray oblique rays observe

its journey further down to the true earth

the black earth between roots now grown diffuse

now weighted with such gravity of mist that

the transparent body rendering all things visible

becomes a thing glimpsed at the very moment it loses

its serve, the light dying in the sky but then occurring

to the earth so subtle in its conquest

that it colors it blue and green bathed in ponds

clogged with the maceration of faines

the water rising through the scum and us drinking

this luminous humor called shadow

for lack of a better term

Combining a variety of free-verse forms and prose poetry, the shapes Darras’s poems take reflect the multitude of significant meanings arising from the singularity of the Maye, a long if minor river that flows from northern France into the Atlantic, the thread connecting centuries of various peoples, cultures, and religions. From the prose poem “I Maye”:

The Somme forgets herself, digging herself further into endless stagnant dreams. Once she has passed by the abortive heights of Amiens, she spreads out into the cultivated market gardens of the marshlands, and even into a number of artificial ponds called tourbières (or peat bogs) where she hides her lowly ambitions. There, around Long and Mareuil, she seems to barely skim along the surface of herself, here and there offering small ear pockets for the catching of fish. Then, suddenly called back on course by a canal from the times of Napoleon where Boucher de Perthes invented archaeology, she steals away in a long straight line toward the sea, her duties now accomplished, her work now hurried toward its end. But the Bay is there to receive her, to invite her to kick up her legs in the dance of its tides.

The history of a place and its people as revealed through its landscape. One can only hope to see a translation of the complete La Maye, especially from the hands of a translator as exacting as Richard Sieburth is here.

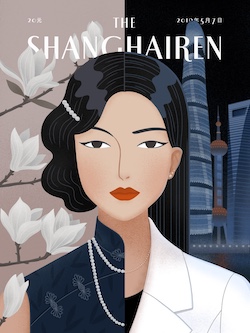

The Shanghairen

The Shanghairen

Benoit Petrus and Vicki Jiang (Eds.)

Zhejiang Photography Publishing House

ISBN 9787551433075

Like its predecessors, The Parisianer and The Tokyoiter, The Shanghairen presents mock-cover illustrations, in the mode of The New Yorker, that depict discrete moments and amorphous feelings representative of a single city that are both myriad and uniquely distinct to a specific place and the mindset it evokes. For The Shanghairen, over 80 illustrators—many from Shanghai, others who have lived and worked in the city—depict the sprawling megapolis of (currently) 25 million people, their moods and attitudes. The book’s left-hand pages (in dual Mandarin/English) present a brief bio of each illustrator along with each illustrator’s comments about their cover image, and the right-hand pages present the image across the full page, in full color. The topics range from icons of Shanghai, such as the Oriental Pearl Tower on the Pudong side of Shanghai’s Huangpu River, to quiet moments in older, quickly vanishing neighborhoods, and thus also embody the ongoing tensions between the old and new. (I’ve discovered some new destinations to check out next time I’m in town, places far below the tourist-radar.) And the illustrations are uniformly good (the book also serves as a portfolio of sample work for commercial art directors looking for new talent).

My sole nit to pick with this book (and, by extension, the other New Yorker-style projects related to this one—all but The Parisianer originating in far-eastern cities, including Beijing and Hong Kong) is that The New Yorker serves as a type of template used to convey a sense of cosmopolitan sophistication and urbanity, and it is New York that serves as a benchmark for all cities around the world, who turn to New York for determining the conditions that qualify a city for such appellations as “sophisticated,” “urbane,” “cool,” etc. But if that’s what it takes to attract readers and potential travelers, so be it. The illustrations are personal views and interpretations of a city that means much to those who depict it, and such feelings aren’t conveyed by mere photographs in travel guides.

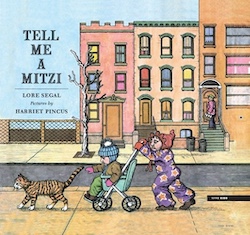

Tell Me a Mitzi

Tell Me a Mitzi

Lore Segal, story / Harriet Pincus, pictures

NYRB Children’s

Oranges, browns, purples, and greens dominate Harriet Pincus’s illustrations of downtown New York City tenement neighborhoods, circa 1970, and a family that live in one of them. The three interconnected tales told by the mother and father (which were made for being read aloud) arise as requests from Martha, their daughter, for “a Mitzi.” Mitzi is a character invented by Martha’s parents, with a strong resemblance to Mitzi, as well as a baby brother and mother and father who also bear a strong resemblance to her own. For Martha’s parents, to tell a Mitzi is to tell her a story about herself that reflects the values they’ve been instilling in her as qualities they already see within her—independence tempered with caution, compassion and resilience, and speaking up for yourself in the face of authority.

For the parents, the Mitzis are also a way for them to explain their responsibilities to Martha, illustrating for her good behaviors, based on what she might do or has done. But author Lore Segal endows the parents’ tales with humor, which rhetorical turns that include turns of phrase—

“Tell me a Mitzi,” said Martha.

“Later I will, said her mother. “Now I’ve got a headache.”

In a little while Martha asked her mother, “Mommy, now is it later?”

“No,” said her mother. “It’s still now.”

—and expressions of exasperation at the numerous small details needed to see to when tending a child, as in the 74-word sentence devoted solely to changing her baby brother Jacob’s diaper:

Jacob said, “Change my diaper.” So Martha climbed into Jacob’s crib and took his pajamas off and took off his rubber pants and took the pins out of his diaper and climbed out of the crib and put the diaper in the diaper pail and took a fresh diaper and climbed into the crib and put the diaper on Jacob and put in the pins and put on a fresh pair of rubber pants and Jacob said, “Dress me.”

There follows another exegesis on dressing Jacob.

A funny set of stories re-telling common (and one very uncommon) family experiences, from domestic chores to common colds.

Maqroll’s Prayer and Other Poems

Maqroll’s Prayer and Other Poems

Álvaro Mutis / Chris Andrews, Edith Grossman, and Alastair Reid

NYRB Poets

Maqroll, the forlorn sailor of fishing boats and small trade vessels, was the protagonist of Álvaro Mutis’s stories and poems about travel, loneliness, nature and metaphysics, which Mutis worked on throughout his life. Born in Columbia in 1923 but living in Mexico for the majority of his life, Mutis’s collected Maqroll stories were published some years ago as Adventures and Misadventures of Maqroll by NYRB Classics. Now, finally, NYRB has brought out the poems and prose poems that formed the basis for the longer stories, translated by some of the best translators of literature in Spanish—Chris Andrews, Edith Grossman, and Alastair Reid.

I suppose the ideal spot to read Maqroll’s poems would be in a hammock in a small shack with a dirt floor in the tropics—humid, dark and dank with living and rotting vegetation, with a mind perhaps still blurred by a recent attack of malaria: conditions giving rise to such questions as “Why am I even alive?” From “Nocturne in Valdemosa” (Reid’s translation):

The north wind moves away, the wind falls silent

and a stifled cry chokes in his sleepless throat.

The silence is answered by another silence,

his silence, habitual silence, the same silence

from which will still spill out, for a brief spell,

the graceful wellspring of his music

like no other music, which hands on to us

the piercing nostalgia of an enigma

that must remain unanswered for all time.

Time, memory, regrets—regrets for abandoning love, for pursuing illusions, for going away from rather than going to—chaos, illusion, and disillusion haunt Mutis’s rueful poems. Here is “Song of the East” in its entirety, translated by Chris Andrews:

Around the corner

an invisible angel is waiting;

a vague mist, a faded specter

will address you with a few words from the past.

Within you, time, like channel water

pursues its gentle, hollowing work

of days and weeks

of nameless, unremembered years.

Around the corner,

the one you were not, the one who died

of your being so much what you are,

will continue to wait in vain.

Not the faintest shadow

to intimate what that encounter

might have meant. And yet

there lay the key

to your brief happiness on earth.

Strongly recommended.