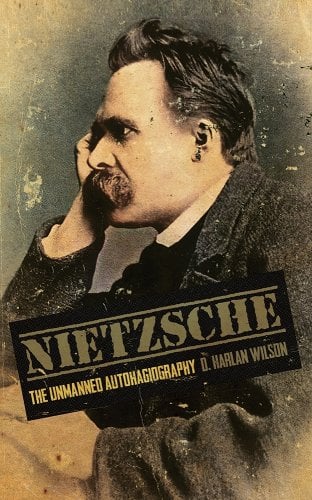

Nietzsche: The Unmanned Autohagiography

Nietzsche: The Unmanned Autohagiography

D. Harlan Wilson

Raw Dog Screaming Press

Comprised of 123 chapters plus 26 rejected chapters and four appendices, Nietzsche: The Unmanned Autohagiography is an unflinching look at the life and philosophy of D. Harlan Wilson. Wilson, the author of Douglass: The Lost Autobiography, Freud: The Penultimate Biography, and Hitler: The Terminal Biography makes his approach clear: “All of my biographies are pretenses whereby I can tell you about my own life and authorship. That’s what everybody’s interested in.” It thus follows that readers are eager to discover the depth of the author’s alcoholism (resulting in frequent bouts of DTs in unfamiliar hotels), his arguments with administrators of the mid-level mid-Western university at which he allegedly teaches, opinions on Kubrick’s films, and descriptions of life in a dreary town called Dreamfield: “Out one window is a toxic artificial lake; out the other window is a gray cornfield; down the fastfood-gilded street is Walmart, the center of culture. All of these facilities smell like fresh manure, even in the dead of winter.” It’s a keen eye (and nose) that can distinguish between fresh and rotting manure, and it’s that kind of discernment in nuance that informs almost every paragraph of this book. (I use the adverb “almost,” since there are textual suggestions that some passages were written while sober.) For readers absolutely uninterested in all things Nietzsche, this book is for you.

Banzaï XIII: Zootrope

Banzaï Editions

From France comes the thirteenth edition of Banzaï: This issue as a beautiful, oversized book of (mainly) portraits by 45 illustrators and cartoonists from 32 countries printed on heavy stock paper and including images and instructions for making your own zoetrope device. Ryan Heshka, Thomas Ott, and Lale Westvind are the only artists whose previous work I was familiar with, yet overall the works and their presentation is excellent, with a wide range of styles and techniques represented. (Click the link to the video for examples.) This thirteenth issue of Banzaï should be on the shelves of anyone who enjoys contemporary illustration as well as advertising managers looking for new talent. (The art here isn’t really “commercial” but could be used to establish anti-corporate cred.)

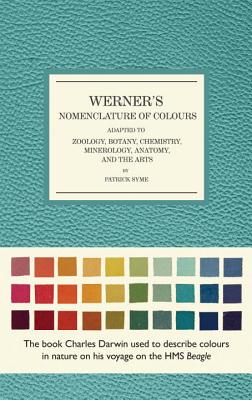

Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours Adapted to Zoology, Botany, Chemistry, Mineralogy, Anatomy, and the Arts

Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours Adapted to Zoology, Botany, Chemistry, Mineralogy, Anatomy, and the Arts

P. Syme

The Natural History Museum

The first and second editions of this short, ingenious book were published over two hundred years ago, beginning as a project by a German mineralogist and geologist named Abraham Gottlob Werner (1749-1817) and, after Werner’s death, British painter and art teacher Patrick Syme (1774-1845). The germ for Werner’s idea was to develop an applicable standard in the arts and sciences regarding the names and character of colors found in nature—mineral, vegetable, and animal—so that scientists and artists worldwide could describe and reproduce coloration with accuracy and precision, despite distances of thousands of miles and/or hundreds of years.

The resulting guide of 60 or so pages is a miracle of concision on par with Mendeleev’s periodic table. On one page is a verbal description of a color and on the other, facing page is a table showing a color swatch for each color described and the corresponding mineral, vegetable, and animal where this color may be found. For instance, under the category of Greens is this description of Mountain Green: “composed of emerald green, with much blue and a little yellowish grey,” and its natural correlatives as Phaloena Viridaria (animal), Thick-leaved Gudweed, Silver-leaved Almond (vegetable), and Actynolite Beryl (mineral). As the description of Mountain Green shows, natural colors embody nuances that require readers to train their eyes to see their subtleties. That Werner and Syme succeeded in finding dozens of examples of these colors in their natural habitat belies the apparent simplicity of a guidebook as succinct as this one.

Modern-day Pantone, in contrast to Werner and Syme, seems to have a monopoly on the field, extending far beyond nature’s palette into neon and day-glo colors. To the best of my knowledge, however, I am unfamiliar with Pantone being used as a reference for anything other than describing commercial products rather than natural artefacts. Britain’s Museum of Natural History, which today publishes Werner’s Nomenclature, markets it as the guide Charles Darwin brought with him on his voyage on the HMS Beagle, presumably with the intent to report his findings with scrupulous accuracy. Although the practice of identifying the composition of natural coloration apparently never took off globally, Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours remains an impressive example of human thought and research.

A King Alone

A King Alone

Jean Giono / Alyson Waters

NYRB Classics

This tale begins during the onset of winter in 1843 in a remote French village, when snow fell every day for over a month, covering everything and keeping people indoors, separated from each other. At one point, a woman leaves her house to retrieve something from the family’s barn and is never seen again. A couple of weeks after that, a teenage boy barely escapes from a man who tried to abduct him, and one of the piglets the boy’s family had been raising is found with a hundred or so razor-sharp carvings in its flesh, the carvings twisted in shapes like an ancient language.

A man by the name of Langlois is sent from a nearby town to investigate the murders, keeping an eye on things over the course of a couple of years, visiting the town occasionally and, during one winter, spending three months living among neighbors familiar with each other but not Langlois. As a man vested with legal authority, he has say over town affairs, and he issues a strict curfew—which all the villagers seem happy to comply with. Overlaying the disquieting fact of the unsolved murders among this tight-knit community is the equally puzzling Langlois, who, while eager to meet and talk with everyone in town, keeps his thoughts to himself.

But one foggy day, a villager spots a stranger descend a tree, then walk away with carefree steps. The villager climbs the tree after the stranger is out of view and discovers the corpse of a woman he had seen just twenty minutes before standing in her front window. Brushing away the accumulated snow, the man discovers the bones of the other murder victims, too. The villager follows the stranger on a long walk of about four hours, right to the stranger’s house. The villager reports his findings to Langlois, who then sets up a posse to round up the man. Langlois alone enters the stranger’s house, one Monsieur V, and a few minutes later Monsieur V leaves it, retracing his steps from the previous day until he, Langlois, and the posse reach an empty field far from town. The posse a couple hundred paces behind them, Langlois then approaches the unarmed Monsieur V and shoots him, pointblank, killing him instantly. The book is now one-third over and is about to get weirder.

Jean Giono was roughly a contemporary of Georges Simenon, best known as the creator of the Inspector Maigret series. Giono was Simenon’s elder by about 10 years and, while Simenon’s novels explore the eccentric actions and mindsets of Paris’s criminals and borderline criminals, especially in his non-Maigret books, his so-called “roman durs” (hard novels) minus the happy endings of the Maigret tales (the bad guys aren’t always caught in the roman durs), Giono was the psychic explorer of France’s rural south, especially as its mean impoverishment affected its residents schemes. A King Alone, however, provides no answers to the three ambiguous tableaus Giono sets up across the novel’s narrow span. The narrative, like the people and places it describes, remains impervious to readers’ attempts to understand their mysteries.

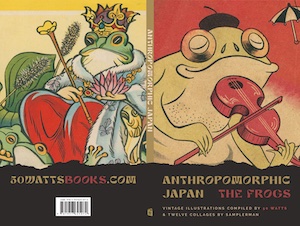

Anthropomorphic Japan: The Frogs

Anthropomorphic Japan: The Frogs

50 Watts Books

An excellent collection of book and magazine illustrations of frogs, as found in Japanese publications from 1924 to 1961. Over 90 pages of vintage illustrations are presented—cropped and edited—with the energy and whimsy of the original publications, displayed across the pages as illustrators might themselves present illustrations. Seamlessly woven into this collection of ephemera for artists looking for reference materials are a dozen collages by a wizard of digital collage, Samplerman (aka Yvan Guillo), which sample, fragment, and reconfigure a number of these old images. Art, design, and illustration practitioners / fans, as well as Japanophiles, take note.

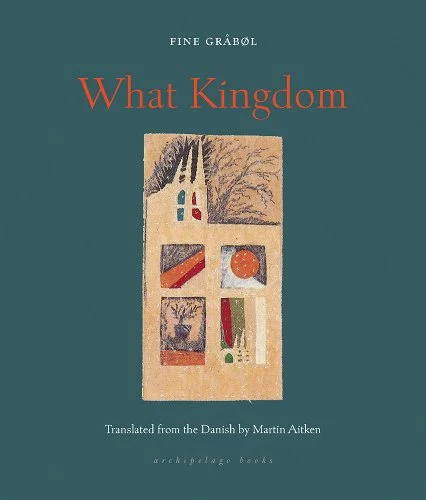

What Kingdom

What Kingdom

Fine Gråbøl / Martin Aitken

Archipelago Books

Taking place in a Danish asylum, What Kingdom tells the story, from the viewpoint of one of the asylum’s inhabitants, of living with profound mental illness in a government-run institution. Shunted to the institutions in late adolescence, usually after spending years of their youth in and out of hospitals, the institutions exist to allegedly help these young people eventually transition to a life of independence. Which of course they are incapable of leading. Schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder, profound depression, and illnesses of compulsion and diminished mental capacity—especially in conjunction with heavy medication—ensure that all of them will need supervision for the rest of their lives (generally shorter than the lives of the greater Danish public). Many of the residents have been abandoned by their families, and periodic cuts to government funding make insecure their level of care and its quality, a fact that constantly hovers over the social workers, doctors, nurses, and attendants who emotionally invest themselves in the care of this vulnerable class. The U.S., of course, eliminated such facilities—where, admittedly, often cruel treatment was endemic to the system—back in the 1980s, so that now the mentally ill are usually found living homeless on the streets or serving time in prison. On the other hand, while people like What Kingdom’s narrator find themselves institutionalized for life, people like my ex-wife, who shares the same diagnosis as What Kingdom’s narrator, find themselves working as administrators at the University of Michigan, making six-figure salaries.

I will breathe like grass: Selected Poems of Gu Cheng [Chinese language edition]

October Arts Publishing, ISBN 978-7530210895

Gu Cheng (1956-1993) was a poet of the Chinse “Misty School,” characterized by its use of vague descriptions and allusive metaphors during the Cultural Revolution—a chaotic period of life in China towards the end of Mao’s reign, which he unleashed upon his own nation, lasting ten years and so uncontrollable that even the national judiciary was disbanded. The violence occurred under the aegis of the Red Guard, whose stunted views of the arts repulsed the Misty School’s members. But, for the sake of their own lives, who needed to avoid phrases and images the Communist Party—the Red Guard in particular—deemed “counterrevolutionary,” and thus subject to severe punishment.

Gu and his wife emigrated to New Zeland in 1987, where he taught at the University of Aukland until his death at age 37 in 1993. He committed suicide by hanging after killing his wife with an axe.

A small bookstore about a quarter the size of the Book Beat—Le Kai Books—is in the mezzanine of an arts-oriented building about a ten-minute walk from where my wife and I live when I teach in Shanghai. Like the Book Beat, Le Kai Books is also run by a husband-and-wife team, the husband also an artist, and the store’s selection every bit eclectic as the Book Beat’s. I asked the wife—whose given name translates to “Snail”—I asked Snail who her favorite poets were, and whether she could recommend a couple of books to me. One of the two Snail recommended was a book whose title translates as I will breathe like grass: Selected Poems of Gu Cheng.

What follows are five translations by me from this collection. Mind you, I don’t read a word of Mandarin, but I thought learning how to translate might be an interesting exercise. I set up a few criteria for my translations: I would begin by scanning each poem with a translation app. I assume that AI has no capacity for allegory, metaphor, allusion, or linguistic idiom. (It’s called “artificial intelligence” because . . . it’s not really intelligent.) But at least AI gave me a clump of clay to work with each. Mandarin lacks articles and verb tense (don’t worry: AI’s translator gave me those). Indications of general or specific subjectivity and the time of an event’s occurrence must be expressed differently.

My aim is to produce in idiomatic English a mental experience akin to that of a Mandarin speaker, who learns to see and understand the world than the English speaker because the relationships among nouns and verbs are understood differently in a language lacking articles and tenses. Articles and tenses are semantic tools the Mandarin language has learned to express differently.

I can’t say that I’ve succeeded. These are initial attempts; much work needs to be done. But I hope they spark interest in his work. These are the first five poems that appear in I will breathe, written between 1964 and 1970.

Gu Cheng’s Introduction:

Since childhood, a drop of dew, an ant’s onus, an old man’s sigh have moved me, shocked by grandiosity, lightning, crowd roar, and endless night sky. Expectant and doubtful on occasion, immersed in whole-hearted thinking about what is ultimate that shines in all small things.

I like reading, I don’t like school, I like to communicate with people, but I don’t like to be reasonable with them. I self-consciously began writing poems when I was 11 or 12 years old. After enduring Cultural Revolution turmoil and roiling life in the countryside, I worked as a carpenter, handyman, cinema advertising painter, editor, and reporter.

Life is the reason I write poetry; poetry also portrays my life. In May 1987, I started a new life in New Zealand, where I lecture and teach.

Poplar

One arm lost

one eye opened.

Cold Autumn

Dead leaves run on

streets; dead branches

howl in the wind.

Frost, who lost her beautiful

green frock, looks forward

to her warm snow robe.

Chimney

Chimney: giant,

astride flat ground,

ceaselessly smoking

cigarettes, looking at

light-filled land.

Thinking about something no

one knows.

Origin of Stars and Moon

Branches that yearn to tear

sky

poke only

pinholes

skylight outside skylight

that people call

moon and stars.

New Home

Quiet dreaming within

quiet night where roosters sing

of dawn within

quiet night

Startled sleepy fire

jumps from the furnace

scaring shut stars watching

from door cracks.