I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, ephemeral, small press, comics, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If you notice titles unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at: I arrogantly recommend…

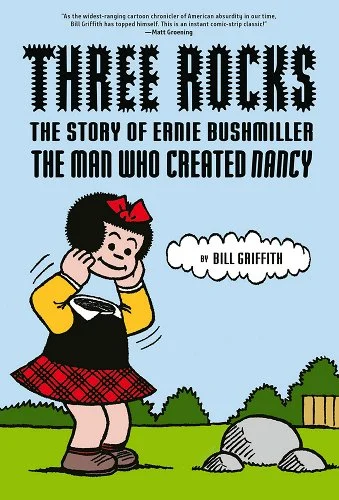

Three Rocks: The Story of Ernie Bushmiller—The Man Who Created Nancy

Three Rocks: The Story of Ernie Bushmiller—The Man Who Created Nancy

Bill Griffith

Abrams

In some ways it seems odd for a publisher to print a biography of Ernie Bushmiller: The medium through which Bushmiller’s works were published—print newspapers—is almost entirely dead, as is the daily comic strip, which Bushmiller cranked out for nearly 60 years (i.e., nearly 22,000 gags!) Far from serving as merely a post-mortem assessment of an historical curiosity, Three Rocks is an excellent and satisfying recreation of Bushmiller’s life and the industry he worked for. Bushmiller is lucky in having Bill Griffith write (and illustrate) his bio: Griffith’s own “Zippy the Pinhead,” in its daily comic strip format, has been around for about 40 years (add another 10 years to that when Griffith was writing and drawing Zippy in full-length comic books). Griffith knows cartooning and the demands of a daily production schedule. Griffith is a huge fan of Bushmiller’s “Nancy,” whose feel for the absurd clearly influenced his own development, and he handles Bushmiller’s private life with respect minus hosanas.

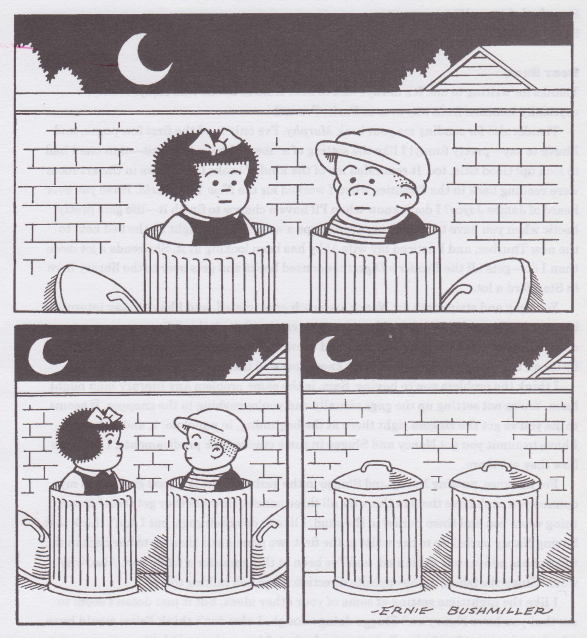

A strip drawn by Bushmiller in response to Beckett’s first (missing) letter. (c.f. EB letter of Sept. 11, 1952; subsequent SB letter of Sept. 18, 1952.)

That said, Bushmiller’s life story is pretty barebones: A job in his teens for a newspaper led to meeting professional cartoonists who taught him the rope; early lucky breaks he had the good sense, talent, and confidence to take advantage of; and the extreme good fortune to have a career he absolutely loved and could do anything with. He seems to have had a happy marriage—certainly it was long-lasting—and good friendships. His career was free of scandal, and his personal life free of mentally and physically debilitating habits. As Bushmiller himself indicated during his life, there really isn’t much to write about: All he did was focus on Nancy.

His focus on Nancy was about as wayward as his habits went. Griffith recounts several anecdotes from across the decades of Bushmiller’s life when Bushmiller either almost crashes his car or is unable to follow his wife’s conversation because he’s obsessed with mentally working through a joke. He clearly loves spending his life this way, never resenting his creation or the demands it placed upon him. (At the height of “Nancy”s popularity, the strip was syndicated in nearly 900 newspapers worldwide.)

This lack of incident no doubt accounts for the many pages of this bio wholly given over to reproducing “Nancy” strips and for Griffith spending about a dozen pages (or 5% of the entire book) on the Bushmiller-Beckett hoax (minus the illustrations!)—an elaborate story conveyed through a series of letters purportedly initiated by Samuel Beckett, a big fan of “Nancy” who sends along some gag ideas to Bushmiller. Griffith no doubt feels that Bushmiller is best represented by his work and succeeds in demonstrating that his devotion to his wife and Nancy really was the whole of his satisfied existence.

If you only know Griffith through his Zippy the Pinhead character, you owe it to yourself to read Three Rocks: Ever since he published Nobody’s Fool: The Life and Times of Schlitzie the Pinhead, Griffith has shown himself possessed not only of a finely absurd mind but of great sensitivity toward his subject and an eye for the telling detail that reveals much about a person’s inner life.

[Ed. note: for more intrigue visit The Beckett / Bushmiller Letters]

The Frisco Kid he never returns

The Frisco Kid he never returns

William S. Burroughs

Tangerine Press

In the early ‘60s, the writer Iain Sinclair, in college, decided to start a literary journal with university grant money, and received a three-page story from William S. Burroughs, then living in Tangiers, to publish. For its own reasons, the university pulled the plug on Sinclair’s journal, and Burroughs’s story did not see print in the form Burroughs mailed it, until now. At the time Burroughs wrote it, the early ‘60s, he was steeped in experiments with cut-ups, many of which were published by small presses, sometimes just mimeographs—cheap, small runs in a wide array of sizes, many of which were Burroughs’s duplications of multi-columned publications such as Time magazine in particular and newspapers in general. In addition to how Burroughs’s words were formatted (i.e., columns) was the consideration of how they looked, given that the cut-up method was an approach for generating both texts and pictorial elements: word and image were one. Burroughs’s hope was that the disjuncture created by cutting up and reassembling words and images would disrupt conventional trains of thought, conventions established by rules of grammar and commercial practice (advertising, government propaganda, genre fiction). Only by breaking the bonds of conventional thinking could genuinely new ideas be borne.

Whether one accepts Burroughs’s assumptions about how words, images, and thoughts work and are generated, one is still left with the odd effect created by such texts as “The Frisco Kid,” a grid of nine paragraphs split lengthwise across three pages, intended to be read from top to bottom, bottom to top, diagonally across the pages—however one chooses. This was back in 1963, when such explorations were still wholly new. The paragraphs are composed of the same elements in different order and sometimes with or without words the other paragraphs lack or have: repetition with difference, as the composer Morton Feldman might have said (as his did of his own works): sound and image never quite syncing, although the “story” seems to be largely the same—the police have questions for two men who shared a room in a boarding house, as recollected by an unnamed narrator:

“. . . You see now gestures in the air over me breathing blue dawn on a dim luminous shore the crying of gulls his hand on my shoulder click of distant heels ah here we are room 18 patch corduroy pants a lamp on the night table a man undressing his back caked with tide flat mud slow cold whispers in my throat and the words were mine once: ‘Pier 18. The Marie Celeste out of Halifax.’ Old friends of the innkeeper told me the captain remembered a kid standing there until I asked for a room: (‘Sharing the room with another gentleman?’) Who else so stretched and torn from the sea Glasgow 1888 pushed open the frosted glass door? The innkeeper got up slow and leaned on the bar a heavy crippled question.”

Iain Sinclair adds to this slim book his recollections of the time surrounding his aborted publishing efforts and an essay on Burroughs in Tangiers while writing this story. The photograph included in the booklet—taken in Tangiers during the time Burroughs lived there, of a man, his backed turned to us, dressed as Burroughs tended to (always with the Brooks Brothers suits, no matter the opioid addiction) with similar posture—haunts the description in “The Frisco Kid” of “his hand on my shoulder,” a hand always moments away in the story, whether of affection or for arrest, always ambiguous.

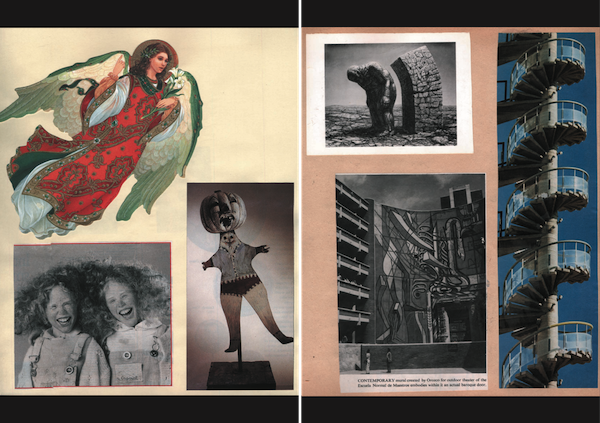

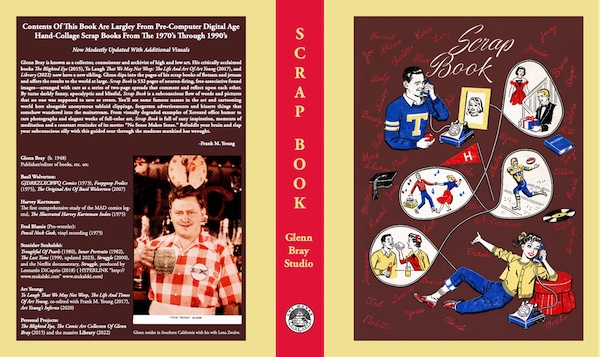

Scrap Book

Glenn Bray

Art Works Fine Art

Glenn Bray collects high- and low-brow ephemera from local newspapers, magazines, comic books, yearbooks, and other venues for weird and obscure news and images. Thousands of them, it would seem from the contents of Scrap Book and its predecessor, Library. One can imagine an exasperated mate shouting, “Where the hell are you going to put all this stuff?” While the correct response seems to be “Here”, it’s too short a response to give any indication of the amount of time taken to become familiar with the thousands of images reproduced here, remember where each is located, and remember across time and place which image might look best juxtaposed with which image. Over 500 pages of facing images fill this oversize tome, each commenting on, enlivening, and/or twisting our appreciation of each other.

Arranged by theme or topic, the book meanders in the manner of free association, where the various topics and themes develop and morph in a friction free environment of endless visual segues. Scrap Book is ideal for lovers of commercial art, high and low culture in tension with each other, absurdity, design, and collage. (Although Scrap Book isn’t an exercise in collage, it’s a kissing-cousin to it.) It’s an acid trip for teetotalers and an extra kick for those already tripping.

Strangers Wave

Strangers Wave

Vik Shirley

Zimzalla

At the height of the pandemic, on the heels of a divorce, why not honor the memory of Ian Curtis as a triumvirate of misery, disappointment, and death? Assembled as a series of postcards, this visual poem consists of photographs pasted upon with lyrics and recovered memories: The photos looking snapped on a dull fall day full of leaf litter, taken on the way from Ian Curtis’s home to his cemetery plot and back again. The words, cut-up a la Burroughs, becoming as much visual information as the photos themselves, their juxtapositions evoking other times, moods, and places once promising as much as they foretold. A perfect companion for a blue day.

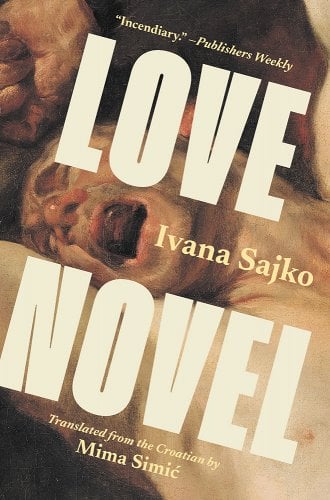

Love Novel

Love Novel

Ivana Sajko / Mima Simic

Biblioasis

An unemployed couple with a child live in an apartment building whose residents can hear their bickering every day, every time of day. She is an unemployed actress, he an unemployed scholar of Dante. Together, they smoke and drink too much, feel trapped in lousy lives, scream at and smack each other, while their baby looks on. Presumably the country is Croatia, home country to the author and translator, a small country poor in resources and high in unemployment, corruption, and civic inefficiencies. Notions of romantic love won’t pay the bills. The narrative alternates between the woman’s and man’s moments free of each other.

Ivana Sajko’s narrative—rendered in English by Mima Simi? with seeming effortlessness—is told in the third-person with an omniscience transparent enough to be led by the rhythms of each character’s thoughts and speech, as in the opening to Chapter 6, in which, after yet another argument, the husband finds himself yet again assigned to sleeping on the couch:

It’s not the first time he’s taken the bedding over to the couch to crawl under the duvet as if at gunpoint, it’s not the first time she’s asked him why he doesn’t leave, humiliating him with the fact that he’s got nowhere to go, and it’s not the first time she’s forced him to admit things he otherwise lacks the courage to say; how much he hates coming home, how hard it is to drag his feet up the stairs and unlock the door, his stomach tied up in knots, nauseously walking down the hallway, anxiously looking around the apartment for her body among the furniture because he expects to see her there, hanged, poisoned or slashed, with a sneaky message left on the kitchen counter explaining she’s done him a favour.

Into their mutual recrimination and self-pity, a short-lived but hope-filled reprieve enters their lives: She gets a job as a hostess at a film awards ceremony (which allows her to dress in period costume) and he gets an assignment for a newspaper on local government corruption. For her, the gig doesn’t last longer than a few days; for him, the paper has no intention of exposing corruption or of paying him for his efforts. Together, they live in a society without interest in or support of the arts or rule of law. Together, with their child, they live a life embedded in impoverishment, nomadically going from town to town as they are evicted from their apartment for failure to pay rent and utility bills. For failure to abandon their dreams, however unrealistic. Still, they retain enough hope to believe, when they tell themselves, that someday, we’ll look back on all this, and laugh.

The Explosion of a Chandelier

The Explosion of a Chandelier

Damian Murphy

Occult Press

Taking place in the late 19th, early 20th century in Spain, The Explosion of a Chandelier involves the occult practices of, mainly, two high school boys, Vito and Héctor, and sometimes another named Renato, who, at first, play pranks on various people, from writing anonymous letters against a bank teller, to asking strangers to identify the place and contents of ambiguous photographs Vito has found. One day, however, Vito takes Héctor to the House of Amaryllis, which seems to be a cross between an old-fashioned gentleman’s club and a hotel, and enrolls Héctor in a secret society, whose initial duty requires Héctor to enter an elegant room that has in its center a vase through which a metal rod, an antenna, emerges. From this rod emanates a high-pitched tone that seems simultaneously monotonal and melodic. The tone puts Héctor in a good mood, and he emerges from the room several hours later, with no memory of having left the room or what he did. The pleasurable feeling lasts several days.

While The Explosion of a Chandelier is an occult tale, it is an occult tale without dramatic rhetorical flourishes or weirdness, or the use of outdated phrases or invented Latinate words. Instead, all is presented matter-of-factly and spare. Although the novel hints at the erotic, it explores more of phenomena Einstein dismissed as “spooky action at a distance”—in this case, the connection between the Lynchian House of Amaryllis and world historical events.

The Many Assassinations of Samir, the Seller of Dreams

The Many Assassinations of Samir, the Seller of Dreams

Daniel Nayeri, with illustrations by Daniel Miyares

Levine Querido

This YA title begins with the 12-year-old protagonist, an orphaned boy being chased by an angry mob, who pelt him with rocks while he runs away. Taking place during the 11th century along the Silk Road, a 4,000-mile-long trading route joining China to the Middle East. A trader on the route, named Samir, rescues the boy from the angry men by trading them bolts of fabric in exchange for the kid, whom Samir promptly names Monkey. Monkey is now Samir’s slave compelled to serve his master. Samir’s burden is light—he’s more hat than hair, although he succeeds in offending many of the people he trades with because his stories about his merchandise turn out to be more satisfying than the merchandise itself.

Samir and Monkey are part of a caravan large enough to fill a small village. When we meet them, the caravan is already in the midst of the travelers’ leg through the Taklamakan Desert, which has sand dunes rising as high at 1,600 feet. Monkey’s goal is to buy his freedom back from Samir. But, given that he knows no trade, has no skills, and lacks money and material goods, how Monkey will muster the money or goods to buy his freedom is the challenge before Monkey.

Fortunately for Monkey, Samir is so widely despised that at least half a dozen former customers and acquaintances want him dead. Samir’s death wouldn’t be enough to free Monkey—somebody else would just take Samir’s place given that Monkey is just a powerless kid. But, as it turns out, having a knack for saving Samir’s life might turn the deal. To do that, though, Monkey will have to become just as wily as his master—without compromising his sense of right and wrong.

To the buyers of books for young adults, I would note that the violence and threats of violence in The Many Assassinations of Samir, the Seller of Dreams is never gruesomely gory, realistically threatening or gratuitously frightening in its details. It is a story of a young lad learning resilience and self-confidence in his status as a semi-autonomous human being.

[ Ed note: Watch an intereview below with the Newbery Honor award winning author Daniel Nayeri at the Library of Congress]

The Musical Brain

The Musical Brain

César Aira / Chris Andrews

New Directions

According to César Aira, rather than outline plots for his stories, he improvises them. Henry James once said of his own writing, he put four characters in a room to see what would happen. James was hardly an improviser, but the notion of setting down a character or incident, then following wherever the lead goes is a principle of choice aligning both authors, although Aira has more of an affinity for whim than James ever allowed himself. Just as in jazz, where not every musical idea bears equal fruit, in terms of time devoted to developing a theme, Aira’s imagination allows him to develop an idea over the course of 80 to 120 pages; but in the case of The Musical Brain, a collection of short stories penned over a couple of decades, some of his ideas are explored and developed more quickly.

And so, while waiting for the next semi-annual appearance of a new novella from Aira, there’s always The Musical Brain—20 stories as whimsical, imaginative, and impromptu as his novellas, but shorter in themselves and three times as long, collectively, as any of his books. For readers unfamiliar with Aira’s works, the narrative tone is almost always that of a voluble raconteur eager to chat away about something he’s been thinking about, saw, or overheard. There are stories about origami, classic Hollywood films, the individual drops of oil paint comprising the “Mona Lisa,” and so on.

Aira’s attitude toward literature is stated in the last story, “Cecil Taylor,” the least fictional of the 20 stories, a story about the avant-garde composer and pianist whose motivation was constantly challenged in the face of relentless rejection:

[W]hat counts in literature is detail, atmosphere, and the right balance between the two. The exact detail, which makes things visible, and an evocative, overall atmosphere, without which the details would be a disjointed inventory. Atmosphere allows the author to work with forces freed of function, and with movements in a space that is independent of location, a space that finally abolishes the difference between writer and the written. . .