A Trip Down the Yangtze River by Tom Bowden

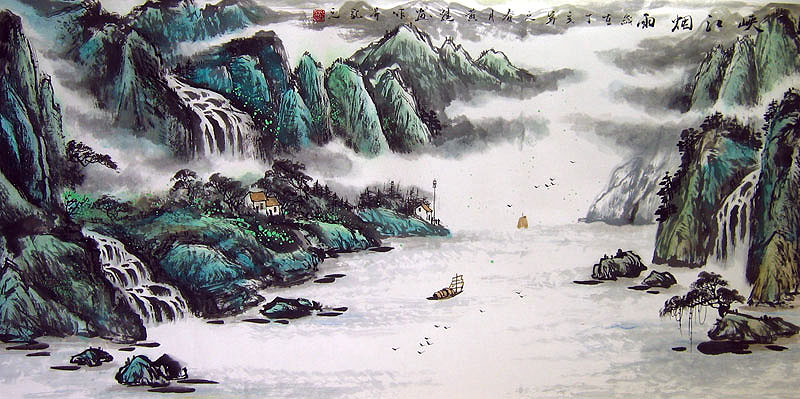

In early October, during China’s national holiday (akin to our July 4th but lasting a week) we took a four-day cruise down the Yangtze River, the world’s third largest river, after the Nile and Amazon, and subject of many classical Chinese paintings. As it turned out, the mountains the Yangtze flow through are just as misty today as they are depicted in the paintings—those mists are no sentimental acts of nostalgia. The cruise ended near the Three Gorges dam, a monstrous feat of engineering completed in 2006, requiring the evacuation of over one million people and countless towns and villages that were flooded out once the dam was opened. (A few thousand stubbornly stayed behind. They died in the deluge, of course.) While the relics of these submerged cities would seem to make for fascinating scuba-diving expeditions, the government has banned them, not out of safety concerns but because the government is averse to showing any part of China as a site of ruins. (The notion of what it means to be Chinese seems to embody geography as much as language and culture. Apparently there are science fiction stories by Chinese authors in which the solution to Earth’s environmental crises isn’t to abandon the planet but to move the planet so that China, the physical place, remains.)

With the Three Gorges Dam in place, the Yangtze rose nearly a thousand feet, meaning that the views we took in—which certainly must satisfy any definition by the British Romantics of the sublime—were even more impressive before the dam, when the mountains would have towered an additional thousand feet above us.

Along steep hills are occasional stairs down to the water, descending at a near 90-degree angle, carved from the rock itself, without railings and, I assume without OSHA approval. The stairs lead up to outcroppings whose brush and trees obscure huts built behind them, although sometimes dwellings built into the rock could be seen, too. People who live in these isolated dwellings farm small plots of land and catch fish. Skiffs from the outside world visit occasionally, bringing supplies and, I image, goods to trade with whatever spare items the cliffdwellers might have at hand. I recently read that, by the Chinese government’s own account, 600 million of its people make $140 a month or less. These are the homes of the “or less” people.