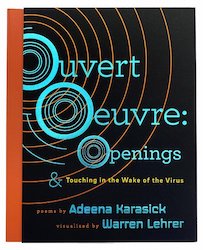

Ouvert Oeuvre: Openings & Touching in the Wake of the Virus

Ouvert Oeuvre: Openings & Touching in the Wake of the Virus

Adeena Karasick and Warren Lehrer

Lavender Ink

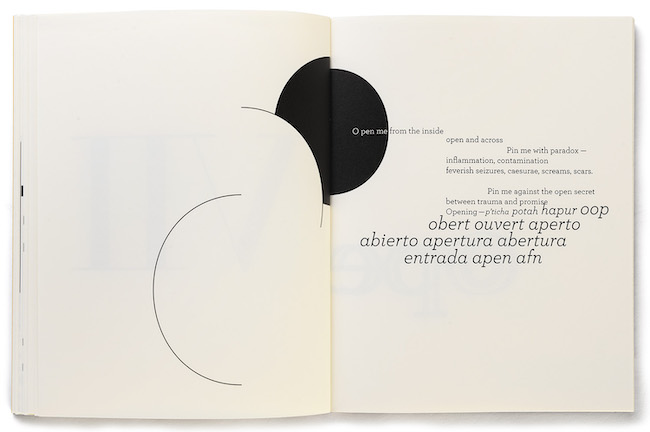

A total work of art, Ouvert Oeuvre combines poetry, typographic design, and music as a single unit. (The soundtrack, including Adeena Karasick’s reading the poems, is available via a link: https://soundcloud.com/earsay/karasick-openings-book-soundtrack, which allows one to read / view Warren Lehrer’s typography along with the aural presentation.) The music and sound design are by composer/performer Frank London, who helped revive New York’s klezmer scene in the late 1970s.)

The book/performance’s two poems—“Openings” and “Touching in the Wake of the Virus”—express a re-awakening of body and mind after two years of seclusion imposed on all of us as a precaution against Covid. The poems demand a performance and exuberance that matches their look and (musical) sound, to be heard aloud (and ideally among other people) for their puns, alliterations, allusions, and sheer sonority of enunciation. Here are two passages (not typographically represented) from “Openings” and “Touching,” respectively:

Opening to what constant reader

whose open wardrobe what cold open

of which open sea whose open mic just

open my head and the high windows

Open this day, this door this open house. . .

For, what lets itself be touched touches its border

touches only a point,

a limit,

a surface;

as a tangent touches a line

without crossing it

So just tttttouch me —

In making this total artwork, the book’s physical make-up, too, has been considered—materials, papers, and construction. It is a reward for those who have survived and endured—so open the book, touch its surfaces, and enjoy.

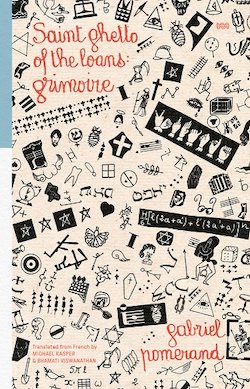

Saint Ghetto of the Loans: Grimoire

Saint Ghetto of the Loans: Grimoire

Gabriel Pomerand /Michael Kasper + Bhamati Viswanathan

World Poetry Books

Originally published in 1950 in Paris (and long out of print since then) Gabriel Pomerand’s Saint Ghetto of the Loans: Grimoire is an early instance of the brief Lettrism movement founded by Hungarian refugee Isadore Isou, “a philosophy of constant creative renewal in which, among other things, letterforms were to be the basis, the underlying principle, of future artwork” (per the afterword from translators Michael Kasper and Bhamati Viswanathan). For Saint Ghetto, Pomerand accompanies the verbal text with a series of rebuses that act as its alternative representations, acting in ways similar to Egyptian cenotaphs, which employ pictographic language to express a narrative. As the poem goes on, the way in which the rebuses evolve transforms from reading left to write to reading as a sort of syntax-less grammar akin to Chinese ideograms: the images and juxtapositions are all there for the reader to unscramble into something coherent. However, the rebuses here pun on the original French. Thus, the nouns may be easy to find, but the correspondence between text and image of other words and concepts may be more difficult for non-French speakers. Saint Ghetto nonetheless remains an interesting exploration of word and image that simultaneously collapses and expands the affinities between the two. Here are a couple of examples of the text and its corresponding rebuses:

[A] cries for help with a jazz

tune.

xxxxx xxxx [Boris Vian] is a loveable heart, a satyr,

they say, who has however satyrized only his

wife, thus hatching two brats.

But he was a hero fantasy.

In Paris, a Black is a White who doesn’t

rape.

Here, as if in a game of checkers, everyone

can land on a different square. . .

[B] Oh! my neighborhood, my neighborhood,

You stink so of shrimp,

One might be Marseilles.

It’s the point of intersection for all the anar-

chists who have millions in the United States

and have come over here to play pickpockets . . .

Pomerand’s description of Saint Ghetto as a “grimoire” is a bit of a misnomer—internal evidence does not show it is intended to act as a book of incantations, but he may have felt the synergy between word and image to be magical.

A fascinating example of what poetry can be and achieve.

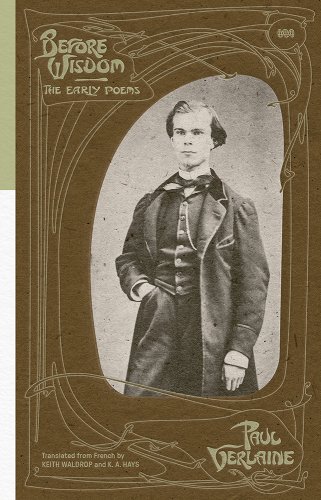

Before Wisdom: The Early Poems

Before Wisdom: The Early Poems

Paul Verlaine / Keith Waldrop + K. A. Hays

World Poetry Books

Collecting selections of poetry by Paul Verlaine from four books published before he was 30 years old, translated by the late Keith Waldrop and his acolyte, K. A. Hays, the poems are formal, metered, and rhymed, expressing a technical mastery of sonority and rhythm, deftly conveyed in contemporary English. The poems follow an arc of loneliness engendered by unrequited love, a romance with melancholy; meeting and courting the 16-year-old woman, Mathilde, who would become his wife, the joy found in their meetings, the woe in their parting, the wonderous love taken in their union; and the ultimate bitterness in their love’s dissolution, Verlaine complaining of betrayal on her part while not admitting to how his drunken, violent behavior toward her may have supplied reason enough for snuffing the love she once felt for him.

“Sentimental Promenade,” which occurs towards the beginning of this anthology could as easily bookend its closure:

The setting sun hurled its final ray

While wind cradled the pale winter-lilies;

Among reeds the great water-lilies shone

Sadly across calm water. Me, I made my way

Alone, taking my wound for a walk

Along the pool, among willows where

Vague mist suggested a stark

Milky-white phantom in despair,

Weeping like a river duck’s prayer,

Answered by a beating of wings amid

The willows among which I made my way

Alone, walking my wound; and the winding-

Sheet of shadows drowned the final ray

Of the setting sun in these pale waves

And the water-lilies, among the reeds,

Great water-lilies on calm water.

Moving a Stone: Selected Poems

Moving a Stone: Selected Poems

Yam Gong / James Shea + Dorothy Tse

Zephyr Press

Born in 1949 in Hong Kong, Yam Gong is a self-taught poet who, rather than being educated in school, began working at age 13, and took up writing verse during breaks on the job at 22. Despite his lack of formal training, Yam is well-read, his poetry has won numerous awards in Hong Kong, and he has been invited to speak at international poetry festivals. Moving a Stone is his first book to be translated into English. For this edition, James Shea and Dorothy Tse have selected poems from his previously published works, translating them into vernacular English, along with its grammar and syntax, creating a poetry any native-born American, for instance, would be pleased to claim as their own.

Here is an excerpt from “Reclamation,” about filling the waters around Hong Kong with land to extend its territory (one form of reclamation) and reclaiming his memories of when the land was first restored. One can imagine an observant laborer, such as Yam, making mental note of what he sees, jotting down those images on his breaks to later transform into a poem, as the sea has been transformed into the island:

I’d wriggle into the most congested places

like a little mouse

under a sweaty armpit, under a piss-soaked crotch

watching with bulging eyes a northerner swallowing a large egg-shaped stone

and spit it back up with blood

a young boatman buying Spanish fly

a grizzled old man smashing bricks on his forehead

lashing each limb with a seven-sectioned ship

then rubbing on the tinctures he hawks

Night after night—fifty cents cures a dozen pains,

ten cents for a piece of gum, chewed

forever, among the cymbals and gongs,

the laboring masses all down-and-out scholars from an ancient story

brushing up against a street opera actress buying fruit candy

and so a life is ordinary and radiant

In “The Subway,” Yam captures both the frustrations of performing demeaning work (with few, if any, options for doing otherwise) and the disorienting fear of entering unknown circumstances if one’s wishes are granted (think of Kobe Abe’s Woman in the Dunes):

Are you more ashamed

to stand behind the yellow line

or to be ripped to pieces

fighting against your lowly position?

There’s more dignity

in the pain of staying put

in life

than in leaping

and yet, there are no witnesses!

Really? Really?

I want to hide my feelings

deep down

like an injured

earthworm

but

where’s my dirt!

where’s my dirt!

“Blind Drifting,” a long poem (which reveal the range of his reading), concerns individual and collective fate, history, chance, and ignorance (despite our best intentions, individual and collective):

Drift toward the birth of tragedy

Drift toward the tinkering of fate

Drift toward the riddle of the Sphinx

Drift toward the wailing song of the siren Lorelei

Drift toward a death foretold

Drift toward a composition arranged by mishaps

Drift toward the unbearable lightness

Drift toward the unbearable heaviness

Drift toward the even more unbearable

silence of the gods

the thunderous applause of the people

I drift, therefore I am blind

But if we are blind to the consequences of our circumstances and choices, on what foundation can trust in ourselves and others be built? The answer is suggested by the title poem, “Moving a Stone” about “a giant stone / no one can move / including me”—me, the person who created the stone in the first place:

. . . death awaits everyone and that fellow

understands it has to be like this

and yet he still tries to please me

Oh, it has to be like this

Everlasting patience:

no one can move

faith hope and love

In the Same Light: 200 Poems for Our Century from the Migrants & Exiles of the Tang Dynasty

In the Same Light: 200 Poems for Our Century from the Migrants & Exiles of the Tang Dynasty

Wong May

The Song Cave

Anne Carson writes poetry based both on Ancient Greek poetry and drama and the fragmented state in which much of it is found, creating a poetry that feels (and is) modern for its terseness and its requirements that we read into what is available by somehow connecting, through implication, the evidence of the fragments we’re given and the stories we sense that link the two.

The Tang-era poetry that makes up translator Wong May’s anthology, In the Same Light: 200 Poems for Our Century from the Migrants & Exiles of the Tang Dynasty, has a similar effect, but not because the poems translated exist only in fragmentary form. The Tang-era poems, too, require readers to fill in the larger picture because of their spare, allusive quality, built upon concrete images, which may be read both literally and metaphorically. Literal readings may leave readers scratching their heads: “Is that all there is?” But their settings—often in the midst of nature or in the company of a fellow impoverished and drunken poetry—suggest that more must be going on, and that “more” is conceptual rather than concrete, as the poems embody aesthetic and philosophical beliefs, often quite different from Western aesthetics and philosophy.

Here is Li Bai’s (701-762 CE) “Imitating the Ancients, No. 9 of 12”:

The living are on their way.

The dead only have come home.

Between heaven & earth,

A travelers’ lodge.

Grieve,

& you grieve over dust,

Nothing new.

The fabled rabbit on the moon

Is still at work

Pestle & mortar

Pounding the elixir

Of unending life.

The Tree of Sun has already been

Chopped down & tied into bundles.

White bones alone have nothing to say.

Pines & firs,

Evergreen

Do not know spring,

A sigh, now then,

A sigh for those

Who went before,

& those to come.

What is keeping them here?

Aesthetically, Wong tells us in her afterword, the form Tang poems take, long or short, are based on a “grid of four lines with five or seven words each (4 x 5 or 4 x 7) or the elongated oblongs of eight lines (8 x 5 or 8 x 7),” each unit governed by the same structure . . ., the end rhymes, rise-&-fall tonal variation, the symmetry of antithetical regular couplets.” Additionally, “A parallel couplet is where every part of speech has to match (noun with noun/verb with verb & likewise the number words, color words, the adjectives, collective nouns) in a four-line poem, the two middle couplets pair up faultlessly. Anything less than felicitous, noun with pronoun, for example, would be regarded as ungrammatical.”

Philosophically, the poems follow Confucian or Daoist thinking about order and harmony. One striking difference in these Chinese philosophies versus Western philosophies is in their attitude toward nature. In the West, nature is something one acts upon; in Daoism, nature just is—to be left alone: any acting upon it will only harm it.

In the Same Light collects poems from 1,200-1,300 years ago by a wide range of poets who left their homelands, involuntarily. “Chinese poetry is unique in world literary history,”

Wong writes, “in that it is written for the best part of 3,000 years largely by exiles, demoted literati among the population in flight from war, famine, floods, natural & man-made disasters.”

Among the exiled is Xue Tao, that rare example of a female poet from the Tang era. Here is her ode, “For Zhang Yuan Fan”:

Halting at the creek where we used to walk

The wading birds know my red skirt,

Will not scare;

I ask you,

How alone can one stand

In the realm of man?

Bo Yao

Broke all the strings on his lute

At the death of his friend,

Sworn to silence.

To the world

Did he sound any different?

Wong May’s 100-page afterward is an accessible yet idiosyncratic and poetic, non-academic discussion of Tang-era poetry that includes, by way of illustration, a floor plan and cabinets, references and comparisons to Ezra Pound and Shakespeare, and interjecting rhinos and speech balloons. One can as easily read the afterword at the beginning, or flip from poet to afterword and back again as often as necessary (the poets and their works are not discussed chronologically): Wong covers more territory than can be absorbed in a straight-through reading (at least that’s my readerly limitation; results may vary), but is an excellent reference in itself to one aspect of poetic history.

Night

Night

Ennio Moltedo / Marguerite Feitlowitz

World Poetry Books

One hundred-thirteen prose poems written in reaction to his nation’s fall into the hands of Augusto Pinochet and his willing accomplices, who turned Chile into a charnel house in honor of fascist glory: One is often struck, reading Ennio Moltedo’s Night, by the parallels to Trump and his acolytes and their worship of murderous thuggery. The hostility of fascist ideology to life-affirming natural forces is succinctly captured from the outset:

At what time must the birds lined up in gardens, trees, and cages sing?

Look to the law.

Permission to live and act according to one’s own nature must be granted by a self-appointed authority in such a country. In our own country, whose so-called Supreme Court has brought to the ascendant the ideology of “original intention” in interpreting the Constitution—an intellectually asinine, factually unsupportable mode of interpretation (it lacks the philology required to support it, assuming its adherents have even heard of the word “philology”)—we veer precariously close to Robert Bork’s ideal:

So as not to annoy, so as to clear the sky and earth of so much progress and to restore the enigma of history, I recommend that the highest and next highest powers—well, all the powers—legislate one more step back toward night: reinstate slavery.

(And, yes, Bork claimed that Lincoln’s emancipation of slaves was unconstitutional. Could Clarence Thomas be any stupider? Why gild the lily?)

Pinochet’s regime regularly engaged in rounding up dissidents, loading them handcuffed into helicopters, flying out to sea, and pushing the dissidents out. Hence Moltedo’s prose poem #12: “They have sent me to the bottom of the sea. Without oxygen, of course. In street clothes, with blue envelope in hand.” (Blue envelopes are Chilean equivalents of our pink slips.)

Leading the nation’s way is “The Champ” (who “goes around telling how he single-handedly defeated half the world”), proud of his cabinet:

For the first time ever, I’m knocked out by what I see, it is (so, so, so) extraordinary—inner sigh number three—that I will offer it now to you. He turns and what do we see: the same assembly of moral defectives, seated in a semicircle, and appearing through a curtain of steam a new-minted male/female idiot looking back at us.

Marguerite Feitlowitz’s translation of Night imbues these prose poems with an immediacy that is frightening and portentous of our own nauseating future. At least climate catastrophe is an equal-opportunity offender.

Soft Tissues

Soft Tissues

Zak Ferguson

Sweat Drenched Press

As it turns out, Covid was a twinned virus. Soft Tissues begins: “A pandemic, built off polemics.” Polemics, the other disease of the time, mediated by media. The world shut down, people locked themselves indoors. The experience of turning on the tube after work was different before the pandemic:

That was our allotted time – to sit back – repress a sigh – when the realities outside of your own front door, your own social bubble, your own town – was shoved down your throat – seared into your eyes. Remember?

When that was our only contact with news bigger than our own mundane affairs.

But during the pandemic, when everyone was shut inside, our access to the outside was provided by corporate entities that chose to monetize fear, hatred, uncertainty, and the violence that resulted:

Now, it is everywhere. Click-bait articles. Never ending stream of fear-mongering, misinformation and ugly – warped – vicious – hilarious – ridiculous – political agendas and all the things, back in them old days, we could easily disassociate from or just turn off.

Zak Ferguson’s Soft Tissues combines internally rhymed prose poetry with aphorism and screed, imbuing his outrage with a rhythm—one line per page building to multiple paragraph-stanzas that abruptly return to single lines again. What has happened when parents cede their responsibilities to computers to shut the kids up?

Keeps the kids happy.

When the parents are away –

In their own heads. . .

The kids will take to their beds. . .

And instead of staying online, in the virtual chambers

They’ll carve words into their neighbours.

Makes the parents proud – seeing them do such neat flesh

stripping tricks – Dad pats gently at his salted tears – Mom with hands to cheeks, eyes glowing – both of them so, so, so proud – of their children’s new next phase of life actions.

“Put that anger and dissatisfaction into something more revolutionary” some of their parents said.

#mydadisnowdead

#puthisbodyintheshed

Made Mom give his dead dick some mummy wank head. . .

The poem takes the tensions exploited during the pandemic and then riffs upon them as a Ballardian dystopia in which babies and youth are literally disposable, where men are perpetually impotent and hetero women are perpetually tumescent: A time of sterile unfulfilled and unfulfilling sexuality in a culture utterly immersed in the pornographic, hostile to the contamination of touch. If that doesn’t count as outrage at the current state of the world’s ethical depravity, I don’t know what does.

On the Blink

On the Blink

Zak Ferguson

Sweat Drenched Press

On the Blink is told by a nameless narrator, one who claims to have forgotten his name, a man without an identity or purpose. Beginning as a meditation on Descartian mind/body duality, it segues into questions of being, becoming, and time, questions suddenly interrupted by a new set of existential considerations, wrapped in the mantle of a manuscript from a stranger about a disorganized life. The narrator mulls over his “Body dictating over mind,” in that “Motion produces many more mental motions”; in essence, there is no mind without sensory stimulus. The puzzle for the narrator is that while his mind is a tabula rasa, his motions and reactions are instinctual. Although the narrator asserts that forms have functions, if rote habit enacts thoughtless intuition, does the result constitute an existence, a desirable state of being? The onset of consciousness seems to consist in resisting rote.

The rhythm and pacing of the novel’s narrative mimics a slow awakening. It begins with a sentence or two per page, the empty space below each sentence indicating silence, room for meditative thought before moving on to the next page and its statement or question. The pages slowly build in amount of text per page, the silences shortening. The narrator’s coma-like existence made up of dull repetition is enacted across the pages by the phrase “I get up. I adhere to the old routine,” the same phrase accruing line by line, page after page, until the entire page is filled with it. Then, in the mode of “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” from Kubrick’s The Shining, the pages display the same phrase in different patterns. The repetition abruptly stops and the narration restarts, a couple of lines per page. In existing in a zone of unthinking rote repetition, identity is lost or unnecessary.

This quagmire is disrupted by the arrival of an anonymously authored manuscript. The manuscript’s narrator is also unnamed, but the narration is written in a Caribbean-sounding dialect by a gay man born in England’s Brighton in 1967, who occasionally refers to reading James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room. In other words, unlike the narrator who is reading the manuscript, the manuscript’s author is steeped in identity. And his chosen place to read Baldwin’s novel is the woods where a man raped and killed two young girls: people who, but for the act of murder, otherwise would be anonymous in an impoverished city, an act which insured all three would be given an identity.

Manuscript turns its focus on the narrator’s younger brother and his dysfunctional parents, unemployed chronic smokers and drinkers. The younger brother, Sam, whom the narrator has lost contact with due to his own dissolute life, has become an artist thanks to the encouragement of a neighbor, a single woman who kept her distance from the neighbors but adopted Sam in her way by encouraging him and doting him with love, a quality lacking in the narrator’s home and the homes of his neighbors. Through love, Sam was given an identity and a goal attached to that identity.

The narrator of this manuscript realizes that although he lacked what Sam was given, he at least took up the responsibility of trying to provide some semblance of trying to provide for Sam what his parents were too lazy, inept, and self-absorbed to give him: some sense of dignity and self-respect, encouragement to go to school, and nonjudgmental explanations of the birds and the bees once puberty struck, rather than the shame and disgust he, the older brother was presented with. Thus, the anonymous narrator can be seen as a kind of surrogate partner working in out-of-sync tandem with the woman who cultivated Sam’s interests and talents. The narrator, though living in poverty still, seems to be emerging from his own drug-fueled coma that stalled his life, shaping from the written observations that form his manuscript a type of hope, a vague reason to endure. There, the manuscript stops.

At this point, the narrator of On the Blink must assess the factors that have left him at sea in his own life, obscurely aware that the manuscript he has just finished holds the key to exiting the existential stasis he has created for himself. He has become the sort of person who gets in his own way and must now find a way around that.

Interview with Zak Ferguson

Soft Tissues deals with the ways in which national lockdowns sparked by the pandemic exacerbated both the inherent exploitative nature of social media and the public’s hunger for it, especially the acts of violence social media seem to thrive on. On the other hand, On the Blink deals with two characters who seem largely cut off from the world, including the anonymous manuscript writer who uses social media to try to track down his estranged brother. Could you elaborate on how you see the cultural forces now acting on and shaping public and personal views and identities?

Soft Tissues is about the pandemic of one’s soul, slowly being mutated and changed, to either fit into one sector or another; to really thrive and feel part of a larger thing, whether it is because of the sheep/herd mentality we humans seem to always to go to, in a strange, often perverse way, maybe because it is much better for us, security in numbers; or to try shape an identity maybe they have always liked the idea of, or have only thus been given an opportunity to really craft.

Those two books, Soft Tissues and ON THE BLINK, share a lot, thematically and with my intent, and in the way I represented the text on the page. What came from Lockdown and the Covid-19 pandemic was the greatest social experiment ever. That isn’t me being a conspiracy theorist, that is me spelling out what Covid became. It was a lie, a myth in the making, a new political standpoint for people to genuflect, to posture and be encouraged by social, to form into a legit social media presence, all so they can babble on and on about issues that were in everyone’s minds, only pushing it to the nth degree, and to its extremis-point.

The reality of what Covid-19 was was not even secondary to what grew online. Covid wasn’t about people dying and the shape of people’s lives being shaped by this unseen force, the lockdown of life, it was the caging of our thoughts, and what is better than ignoring these feelings and attitudes with external distractions, is to take it upon ourselves to give voice to them, and social media gives EVERYONE that platform, whereas before the real rise in social media influence you either had to work hard to earn the right to opine or write, reflect, and share said thoughts/opinions. The internet is the pandemic we all don’t seem ready to admit needs a vaccine, to help disassociate from its mutations and, sadly, appeal.

For the likes of myself it was about there being a sharper focus on our internal world, our weird biases, alt-attitudes, that were somehow reinforced and then built into a gigantic pyre, the fires lit by shares, hashtags, tweets, FB splurges we had as a crutch to fall on.

We all had our digital devices to fall into, whether for entertainment purposes, or a welcome distraction, or however or relationship with the virtual world was, it was the world-wide pill to pop to “cope”, and we could never escape it, nor can we dislocate from the virtual realms. Inside this unreal world birthed, not a new pandemic, has it has always been there, but a different offshoot. Much like the variants of Covid itself.

What it all became was a bloody mess. Covid created a larger canvas for the kooks, the mad hatters of social media to stand tall and spread misinformation. Not only individuals who own more than five email accounts, but for the people who were sadly in esteemed positions of power, to waffle and continue perpetuating all the wrong ideas, codes, and sub-“realities” as they dictated and sold them as.

The fall out of Covid-19 wasn’t the variants and deaths, and Long Covid effects, it was the perpetuation of social media consumption and its “apparent” prevalence and now IMPORTANCE (or do I mean impotence?) to our current generation. It isn’t about Gen Z versus Gen X, we are all part of the same generation, only forcing that pathetic notion that we are set in our ways due to the eras we were raised in. We can all grow and evolve.

Then again, it all seems like a Catch-22 situation by this point.

For me, there was fears, anxieties, being a type one diabetic, more susceptible to such viruses (I believe I contracted Covid early in late December 2019, and was later told by a nurse that all of my symptoms pointed to it being a Covid-19 situ, which plagued me, knowing this unnamed and corrosive thing might have passed from me to other such vulnerable people) and feeling extremely trapped, and not by Lockdown but by this invisible enemy—this being a virus that would wipe out the lesser being, almost put here to test certain individuals, let the strongest man win, kind of ordeal.

During this pandemic there was a lot of reflection, and focus, on textures, and details that I hadn’t yet truly given myself over to, in writing about them, and especially in relation to my autism.

There were also visions, fantasies, creative ways to express what was simmering in my mind, that of an alternative future, birthed from these events created from a worldwide pandemic, situations I have no doubt will one day become manifest. I wrote four non-fiction novels, one after the other, within four months, a weird reflective book series, entitled Interiors for? that was an experiment outside of my usual fully fledged “autistic” experiments, and then there was Soft Tissues.

Soft Tissues stands out to me because it is a small book that has weight to it. It is an epic in its scope. ST was inspired by all these online crusades, lynchings, and the real pandemic, that of which was brewing inside of us all. We had room to roam, to experiment, to declare and to act out. What stands out mostly in writing it, was me and my partner racing on the empty motorways in the UK, which was such an uncommon sight, so surreal, and that of which became a sort of novelty, and I was in that first moment of experiencing it, imagining a world where unwanted babies were flung like trash onto these vast stretches, and bulldozed over, to clean up the mess. A system that was accepted and maybe even encouraged by every outraged dullard online.

Lockdown was no different from my usual existence. I work from home. I spend unusual amounts of time on my laptop, writing and siphoning popular culture to comment upon. Apart from the heightened fear of the end of days, the continual perpetuation of fear, misinformation, and an almost absurd focus on a variety of topics that before I’d briefly acknowledge or humour, it seemed important to process this in a contemporary fashion. At the time of conceiving ST, I was also experimenting with poetry, rhyme, which was heavily inspired by John Cooper Clark, and I was so taken by the whimsicality and musical nature of his punk energy and his simplistic childlike rhymes and poetry, that Clark uses wonderfully, that I wanted to make a point that poetry doesn’t have to be dull or dripping with woe, that or sticking to the GCSE [General Certificate of Secondary Education] level of what we are told poetry is. Another inspiration was the poet, and now a friend, Fran Lock. With her work, there is a playfulness. A new kind of poetry. Dense, personal, epic in scope and honestly singular and, because it came from Fran and everything she has experienced as a human being, and her capabilities and skills as a writer is very powerful and something the world of poetry is lacking. That was enticing, and this was something I hadn’t allowed myself to fall into and marinate in, so it became a new type of experiment for me, to comment on things, as they were happening, and framing them in such an absurdist, yet totally real way.

Politics hadn’t been so extreme, especially for the likes of myself, to the degrees I had to have an opinion on it, and not just that, I had to stake my claim and show people online whose side I was on.

Then, this affliction, this a-political nature needed to be studied and I needed to let me freak-political-flag fly. But that is what Covid ended up becoming about, for me, which was conspiracy and lies and exploitative ways that allowed the systems that be to continue to take the piss.

Theories. Opinions. Wacko-science. Religion. The push for identity, at the most inopportune moments, but, as all things are, in contradictory terms, was also the right time to make a stand. Covid opened a space for people to have voices, some sadly louder than others. A space where in so many ways the phrase, “stop this train called life, I wanna get off!” allowed people to take up arms against police brutality, racist attacks, the rise in criminality and the gradual fall of these systems we are meant to put our lives into, ensuring longevity and sanctity. It is how the real pandemic came from within us, not on a bacterial level, but a philosophical, deeply id-internal level.

With ON THE BLINK, I was going for a weird Philip K. Dick science fiction story. I wanted to tell a story without naming a character, the unreliable narrator, named and focused upon, whilst remaining elusive, and not to confuse people, but to allow one to apply themselves. To hold up a mirror.

I love the ambiguity of Dick’s work, but also the simplicity. The mystery is very much known, that throughout Philip’s history of being a paranoid schizophrenic, that most often his question of identity came from not just a narrative device but as a demon he always struggled to exorcise.

ON THE BLINK is experimental, but very much a science fiction piece about dislocation, alienation, and a want to conform and combine with others. And how? Via the internet.

It is also a damning example of what passes as connectivity in our world now. The lead character knows he/it existed before, in a certain image, premade for him by life and all its circumstances. He or it existed, it had a method, it had a way of life, that on an aesthetical level is surrounding him/it, but that of which it becomes less concerned with. It becomes about just following the same old well-trodden path and not willing to ask deeper questions. But, again, a character that is set as far from the center of where the real meat of the book is, which is the story within the story, the real narrative, that of a brother seeking some connection, reeling from memories and mythologies, pondering on his family, processing his legacy and the poverty he grew up and continues to live within, embedded into place, like some ambered creature that Richard Attenborough’s character from Jurassic Park would froth spittle over. Both books deal with the now, and the future. It tackles with themes of identity, cross pollination of cultures and expectations. I recently started writing a pseudo sequel to ST, called Soft Issues, and one character/narrator in a book of several is readying to drive his van through a street of people, not as a statement of terror, but because he wants to be famous and heard, and before publication I decided not to, due to what recently happened in the UK, and didn’t want to publish it and be called exploitative or insensitive. And it hit me. What was once fiction, is now a reality. All satire or contemporary thought and fiction will eventually turn into a reality. This is what is most frightening.

Both Soft Tissues and On the Blink create rhythms based on increasing amounts of text per page followed by abrupt cuts back to one or two lines per page and building up again. What aesthetic and emotional effects are you trying to impress upon readers when confronting the voices narrating these texts?

I have a habit, with past works, and current writings, of being extremely provocative in how I edit and structure my work. It is unforgiving on the reader. Putting in typos, deliberately deconstructing work that I slaved over perfecting and making the perfect little soldier in the ranks of this literary assemblage. The issue that became apparent was forgetting what the deliberate typos were, placed deliberately therein, and those that were virginal. It can confuse and aggravate whoever has read my work. It surely does annoy me, and in the sentence and page structure, of those two novels, this is me trying to find new pathways to express and create an ambiance, without falling on my usual devices. But I never want it to be disingenuous or fake in the autistic representation or feel exploitative. That’s why it becomes aesthetical, rather than ever dealing with autistic stories and narratives.

In my work I want to talk about the contemporary, to mock, ridicule, satirize; yet satire is now becoming reality. My main point isn’t to tell compelling stories, or to merely fuck with structure and such, but it’s also important to entertain. By experimenting with form, structure, grammar and all the literary values we have been suckered into believing is the ONLY way to go, I want the experience to be different, different enough to be fun, playful, eccentric. And telling. That there are no rules!

To make you stop, pause for a beat, feel baffled, and then respond naturally with, “What the heck is going on here?”—then, maybe, maybe not, it will dawn upon the reader that, “This is something completely different. And hopefully it will goad the reader to realize that… “I can write like this, or I can go one even further, I can get even crazier… I can express, in the ways I have always wanted to, but couldn’t because of what education and literature has told me to not to do…”

There is such freedom throwing caution to the literary winds.

It is a jumble, my prose, a huge chunk of forever fattening prose, with no breaks, no indents, no room to breathe. Information dumping. Sensory overload, which is the fulcrum to an Autistic person’s existence, so in a way I am trying to capture that sensation with the medium of writing, in structure, repetition, and being neglectful of adhering to the supposed literary rules. Autistic individuals are not ones who find it easy to adhere to societal strictures.

Adhering is not easy, and so before we are able to voice for ourselves why this may be, we are labelled as rebellious, punctilious to the uncomfortable, irritants, great disturbers. Nuisances. The Bad apples. Or, depending on the severity of one’s autism, a freak, a monster, a child to be kept under lock and key.

You describe yourself as an Autistic writer. How does that autism manifest itself in your works, and how do you think it affects the way in which you see and respond to the world? In the U.S. at least, there’s a preference for the phrasing “X has autism” rather than “X is autistic,” as a way to avoid implying that a person is somehow defined by whatever condition he finds himself in. Do you find a meaningful distinction between “has” and “is” with relation to autism?

As an Autistic person, going into what you asked, I am autistic, autism is me. I am my autism and the same goes with the autism. There is no autism without its host, Zak. I am autistic, and I don’t just have it. Having something, in a way feels like it can be cured or gotten rid of.

Well, we can’t and nor should we.

I’m not precious about being seen as Zak, the guy who has autism, or Zak the autistic writer/guy. My identity comes from my autism, so I would say though it isn’t what I should be defined by.

I cannot lie, it does though, as autism and the carryover of its affectations and clichés is what makes me act and think the way I do. So, I am defined by it, but I am not merely it!

Whereas before it was framed as, you have autism, as if it was catching, and something almost to be ashamed of having stuck on your lapel like a big gaudy badge. Autism as a diagnosis shouldn’t be used to excuse bad behavior, but it is hard, when these strange, indescribable feelings and sensations up top cannot be named or voiced, apart from stimming [self-stimulatory behavior], tics, and how it shapes our mood and overall demeanour, and you are left, especially those on the Higher-Functioning side of this fluid thing known as Autism, unable to come up with anything but, “I cannot help it, it is the autism, and that means it is just who I am!”—a lump it or leave it kind of situation.

When I realized I was autistic, my identity, and not just a diagnosis to further upset and make me feel alienated, and ostracized, even more than any child or teen feels, I became a better person. And a better writer. I say that we, those who are autistic, perhaps come across as those who revel in rebellion, though, us autistic people, we are without any actual deliberate intent to cause disruption, we are just enthralled to this mental cross-wiring, and we don’t seem to be afforded hindsight, not to the degrees neurotypical people are, and nor are we given the chance to revel in it at all.

In writing and editing and structuring the way I do with previous books I’m finally doing it with purpose and intent. Also, in a way to, not educate, but to try get as close to what I call the autistic experience as I can. I feel experimental writing and art is by nature extremely autistic.

Being Autistic is a bundle of contradictions, and I think that’s where the one to three lines per page method/aesthetic comes from, not wanting to repeat myself, but to also heighten something else, another aspect to autism via writing. The sparse, blunt edge to it all. Brusque. Not of the norm.

Abrasive is a word that has often been used in relation to myself, personally, whereas my work has been called “open, freeing, loud, obnoxious, petulant, and rebellious.” Though it is inherently un- “normal”—it’s effective and kinetic. Also, it isn’t just about autism, my books are about entertaining, enlightening and pushing the form of the novel. I wanted to leave a void on page for On the Blink. Sparse. Empty. Vacuous. Which relates to the nameless narrator. Also, mixed in was a want to create an ambiance different from the more hectic nature of my previous novels/writing.

Which books and/or writers spurred the feeling within you that you must write, that writing was the most apt way for you to get through life, other than, say, sorting letters for the post office or some other dreary work?

I am always getting spurred on by each writer I read for the first time. Like Tom Robbins. Paul Auster. A. M. Homes. So many writers out there. Paul Stewart and Chris Riddell were my first legit obsession. Anything and everything they put out, I read. Beyond the Deep Woods was my first completed novel. A book I chose for myself. Aged 9, and having never wanted to read, being far more interested in films and cartoons, when I read that book, the power of prose and writing/storytelling told me that this is what I wanted to do myself. From then on, my reading habits were varied and unpredictable.

There were two books, in particular, that made me finally decide to try my hand at writing an actual novel. The first was Naked Lunch by William S. Burroughs, and the second was GLAMORAMA by Bret Easton Ellis. Those two books fused together and became a template as to where I wanted my writing to go. William S. Burroughs is the reason I write and took to initiating the process of writing a book and expressing in the way I do. William S. Burroughs seems to me to be a person who wasn’t diagnosed or ever really gave thought to his habits, ways, and behaviors, and to me I think he might have been autistic.

For me it is evident in his works, his art, and his relationships in life. His process and writing were the way I wanted to do my own thing. My philosophical outlook is quite singular and uniquely my own but, then again, I could be completely wrong, but it’s very much influenced and brought to life because of his work. My method is more cut-up consciousness, than applying the Cut-Up Method to a heap of already written works. Though in later life William S. Burroughs soon fell into the whole Cut-Up paradigm without applying the system Brion Gysin and William himself evolved and created.

William taught me this… fuck ’em! Fuck the lot of you! I’ll do this thing my own way. Writing isn’t always meant to be neat and tidy and accessible. Nicola Barker is a writer who is underrated and exceptional. I got into her works six years ago, and what her books offered me was permission to get complex and wild, that the weirder the situation and dialogue, the more fun it can be. That the departmental nature of literature, the so-called mainstream, can be complex and experiential and ultimate in its experimental expressiveness.

There are far too many to name.

You’ve set up a small publishing interest called Sweat Drenched Press. What was the impetus for starting the press, and what sort of stories and ideas are you looking for?

I wanted to house and push works that other small presses overlooked or didn’t believe in. To also nurture artists and create our own branch in this big “small” indie lit scene, to house different voices, from different backgrounds, people of different cultures, race, and identities, and to tell them, your work is good, and it deserves to be put out as a physical totem. To give somebody a shot at getting a book out. Give someone a chance that was never given to myself.

There is no money in this game, not really, and if you are doing it just to get that satisfaction of having a book put out, and somebody, one or ten who go out of their way to review the books and engage with them, that should be enough. I know that sounds awful, on a business side of things, but I am honest. That is the reality. We went so far in our first two years to give the authors 100% of their royalties, and what that did was mess up our own personal finances. And that was when we started to look at this as a non-profit business. The dreaded b word. Business.

Every cent, pound, and dollar made my end, from my own works, goes into the Press, and we are at a point where it is a self-feeding cycle, and luckily where our authors still get money from their works. More so, if purchased directly from our website, as that cuts out the middleman, the greedy Amazon corp.

I think there is a lot of bias, and hugely disproportionate (chest-puffing) egos in publishing. It is dog eat dog. And I hate that. I also wanted to get into putting books out. Some I have failed on, with formatting, and cover designs (mostly my own) but, I strive to put out a book that the author would be proud of, and it is very collaborative, and in so many ways fun, but there have been times where the fun didn’t last long, but that is the nature of the beast.

The Press is here to make a dream come true, and hopefully start you on your journey or contribute to your journey as an author. We want transgressive, not of the norm, form pushing, experimental books. Not only that, but we also seek all kinds of literature, we are not narrowing our demographics. What we are is extremely DIY, punk, and avant-garde.

What books and stories are you currently working on or will soon release?

We have three upcoming releases, the first of them being N. Casio Poe’s MAGENTA SHADOWS, in October of this year, which is another part to his epic Cringe Mythos book series (all books in the series are available via Sweat Drenched Press ) which in N. Casio Poe’s words is about, in a nutshell, “carbonized reams of choleric dispatch from the collapsing sub-basement of an over-dreaming underworld.”

MAGENTA SHADOWS is about flipping back and forth between a gruesome horror story, a true crime expose, and a steamy erotic novel until the narratives bleed together into a single universe of celebratory deviance.

Then we have this Christmas SUPERHERO MOVIES GIVE ME GOUT by Marcus Meltdown, a book that started off initially as a book dedicated to Marvel movies, that then became a novel about what superhero movies mean to both him and the wider world at large. It is hilarious, candid, inappropriate and the kind of book you know will upset and entertain a certain kind of individual. It is the only type of book that the author of STOP BEING A SHIT-CUNT could write. (Also available from Sweat Drenched Press).

Next year, on February 24th we have Dethrone God, which is a book about carrying a darker secret while coping with ageing in world you no longer recognize. It’s existential beat writing.

Also, next year we have Sex Is Capitalism by Craig Podmore. Sex Is Capitalism is an onslaught, an assault, an examination of the futility of modern man. The writings within depict that the enslaved body, the salacious flesh we all desire is prostituted into the construct of materialism and consumption. The body is a vehicle which is used and abused perpetually until malnourished. Herein is a collection of new poems, an introductory essay, and short stories. Craig Podmore uses his serpent tongue once again to dissect the absurdity of the maniacal machine that is known as society.

For myself personally, I am currently working on Sweat Drenched Production’s first feature length movie, entitled SHEET. It is (of course) an experimental horror movie.

I have a few books in the works, one which was my debut novel, which has been expanded and, in all honestly, re-written into a whole other entity. SOFT ISSUES, the pseudo-sequel to SOFT TISSUES is nearly completed, oddly benefitted by the postponement to be bettered, and will also be getting released next year, once I feel the time is right. I also collaborated on a book with Kenji Siratori, which I believe will be released sometime in the near future. Other than that, we are well and truly on our way to kicking off 2024 in a big way. We also have a YouTube Channel that features all the trailers I made for some of SDP’s releases, and my short experimental films, one of which was listed as a recommended watch in the RADIO TIMES. If you’re interested, please subscribe, give a like or share, in relation to anything related to SDP. And thank you so much Tom for this opportunity, and for giving those two odd books of mine a chance.

________________________________________________

Firebird

Firebird

Zuzanna Ginczanka / Alissa Valles

NYRB Poets

Just before Soviet forces ridded Poland of its Nazi invaders (issuing in a new set of problems for Poles), the 27-year-old Jewish poet Zuzanna Ginczanka was executed by the Nazis after being turned in by her landlady, a fellow Pole. Ginczanka was a rising figure in Polish poetry circles during a turbulent time, having her first book, On Centaurs, published when she was 19 in 1936, before Hitler’s calamity was imposed upon Poland. Firebird reprints On Centaurs and a selection of previously uncollected poems written after her first book.

In On Centaurs are poems of dualities—centaurs, heaven and earth, amphibians, good and evil—using iambs and anapests, internal rhymes and slant rhymes at the end of lines. They are poems of observation and comparison. Here is “Pride” in its entirety:

Thick-veined flaxen-haired maidens meet wholemeal youths,

fresh-breathed angels present their astral bodies.

I know:

I’m entangled in good and evil

as in the hundredfold three-leafedness of clover—

Mixed in the bast baskets the apples of all knowledge rattle.

So I’m meant to ask the way

to You,

lost as I am on the crossroads of dreams?

So many times day has blackened blue eyes with black night—

Eighteen faded Junes

screaming

won’t hear

the question—

Eighteen winters won’t hear gray winters dumb as a stump.

Women’s warm leaf-tongues rub and scatter words on the wind—

a fanatical aluminum snake weaves a nest in the paradise tree.

I don’t know, Lord,

what’s good,

what’s evil,

fixed on my eighteen years—

rapt stern and alert

more and more

wiser and wiser

I don’t know.

Ginczanka works primarily with dualism—and/or, yes/no—whether due to youth or inherent tendency, she didn’t live long enough to sufficiently answer. But toward the end of Centaur, in “Declaration,” she begins moving away from or expanding upon dichotomy with three sections labeled Thesis, Antithesis, and Synthesis—looking toward achieving harmony between opposites and differences. “Catch,” which ends Centaur, continues the expansion through a dialogue between a fisherwoman and the sea. Like the uncollected poems that follow it, “Hearing”—an exchange between a girl and a tribunal that judges her—the poems attempt to synthesize a new knowledge between what is seen, known, and experienced, and what is hidden, fateful, and yet to be tasted.

When her premature end stood at the threshold—betrayed by a landlady, arrested by Nazis—Ginczanka responded with clear-eyed understatement:

I leave no heirs, so may your hand dig out

my Jewish things, Chominowa of Lvov [her landlady], mother

of a Volksdeutscher, snitch’s wife, swift snout.

May they serve you and yours, not any others.

My dears, this is no lute nor empty name,

I remember you, as you remembered me,

particularly when the Schupo came,

and carefully reminded them of me.

May my friends gather, sit and raise their glasses,

drink to my funeral and to their own rich gain—

carpets and tapestries, china, fine brasses—

drink throughout the night, and come the dawn

begin their mad hunt—under sofas and rugs,

in quilts and mattresses—for gems and gold.

O how the work will burn in their hands: plugs

of tangled horsehair and soft tufts of wool,

storms of burst pillows, clouds of good down

will stick to their arms and turn them into wings;

my blood will seal the fresh feathers with oakum,

transforming birds of pretty into sudden angels.

We owe thanks to Alissa Valles, whose translation of these poems gives them a new life in a new language and stirs us to remember and resist the hate of our own times.

Abyss and Song: Selected Poems

Abyss and Song: Selected Poems

George Sarantaris / Pria Louka

World Poetry Books

Sky crosses the ether

Breath the passage of years

Rivers children eyes

That stopped images

Words that rendered silences

From lively nights

Concise and compressed as haiku, the poetry of George Sarantaris looks for the eternal and universal in ephemeral moments. Born in Greece in 1908 and raised in Italy, Sarantaris returned to Greece, turning his back on his lawyer’s training to devote his life to poetry, doing so until he died at 36. He was a member of the Generation of ’30, a school of poetry that melded modernism with Ancient Greek aesthetics.

The bees sweetened remorse

And they took the crime on their back

They carried it to the lake and drowned it

And it was warm, the remembrance of sleep

Melancholy and gently rueful, his poetry an existential sigh in ode to fading memories, as in “Memory and Dusk”:

Quietly they pass

by the garden that welcomed us

and sheltered us our whole life,

the hours the women the doves…

Like meditative breaths, they demand to be read slowly. Like Wallace Stevens, they often consider the life of the mind and how it apprehends that which is sensory:

Come sun, my ear

Come take a peek at the mind

It illumines the sea

It orbits the stars

It gives birth to some country

Some country some meadows

Fields orchards

And our silence

Awakens them

In earth’s embrace

Between skies and waters

And voices that flash

With so many wings

With such a quiver no one leaves

No one sleeps

With such a thicket of hearts

No one proceeds into the wind

With a lighter gait

No one ever leapt

Over the abyss of death

Pria Louka—a poet herself and a translator of Greek poetry—has rendered the silences within the poems with as much seeming ease and grace as the words themselves. Highly recommended.

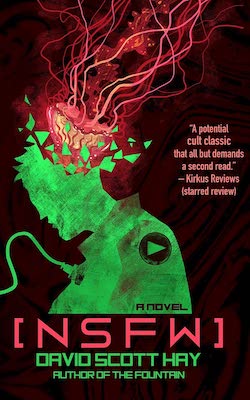

[NSFW]

[NSFW]

David Scott Hay

Whisk(e)y Tit

The setting of this present-day dystopian novel is the office of a corporation known as the face (led by a not fully human Zuckerberg-type, with apt sliminess). People work at the office as contract workers who are told that if they make it past the first 90 days of their jobs as video monitors, they will earn a bonus. Otherwise, they are not “employees,” as legally defined. The bonus will be full employment, with such perks as health care, paid vacation, retirement, and/or stock in the parent company—or so the contract employees believe but do not know for sure. The bonus is left deliberately up in the air, TBD.

This novel-as-warning takes on the social media corporations that monetize our personal information and improve techniques for keeping users online for longer and longer periods, including the circulation of increasingly shocking and depraved materials. [NSFW]’s characters prefer to remain anonymous to everyone—including friends, co-workers and lovers—preferring to be referred to only by their online names—@Sa>ag3 for the narrator and @Jun1p3r for his girlfriend, for instance.

The videos the monitors watch are the worst of the worst: beheadings, rapes, tortures, murders, and other forms of mayhem. All live-video feeds have a 70-second lag that give the monitors time to determine if they are real or staged. Seventy seconds that come in handy when trying to determine if something that looks like, say, a massacre of school children is actually occurring. Two underlying principles guide the awfulness of the videos that are allowed through: (1) any sense of communal sacrifice for a common good is a sign of unfettered fascism and (2) engaging in unconstrained violence every American’s Constitutional right. Or, as presented in these two exchanges from [NSFW],

No one remembers victory gardens. Any sacrifice made for country is now an assault on personal liberties.

That’s an old headshot, you [@Jun1p3r] say. I took it with a Nikon.

Your husband also took a lot of headshots with an AR-15.

Psychologically, the job takes its toll on the monitors, which they counter with a battery of drugs (mainly anti-depressants and micro-doses of mushrooms) and lots of aggressive, on-the-job sex, usually inside their department’s lactorium, a private chamber ostensibly for lactating mothers. Most people only last a few days or weeks on the job and either don’t come back or commit suicide after a steady diet of viewing human atrocities. Those who endure do so just for the chance to have healthcare benefits.

Soon after taking the job, @Sa>ag3 and @Jun1p3r move in together. In addition to frequent bouts of angry sex and a daily diet of micro-dosing shrooms, they place their phones in a chamber that blocks all electronic signals coming in and going out and cover the floor of their apartment with sod and plants to achieve some semblance of sylvan quietude.

Could things get any worse? You bet they can. I won’t spoil anybody’s read, but the book offers a pathway to hope. Consider this your 70-second warning.

Interview with David Scott Hay

David Scott Hay is an award-winning playwright and screenwriter. As a novelist, he was twice-nominated for a Kirkus Prize.

The seam of black humor throughout [NSFW] seems to be the face of outrage that propels the novel. While most people probably think the label “NSFW” refers to sex, that clearly isn’t the case in the work environment of the face, nor is drug use. Instead, the major problem is containing the unrestrained violence whose motivating force seems to be the chance to be witnessed by millions of people. What factors made you tell yourself you had to write this book?

Panic. After Whisk(e)y Tit picked up The Fountain, I realized I did not have a follow-up book planned, and [Whisk(e)y Tit publisher Miette Gillette] might, in fact, want to publish a second book. That was the initial motivator (I’d been working on a middle grade series).

Meanwhile, my brain was busy daily processing the bombardment of different digital agendas aka doomscrolling, the rise in and normalization of gun violence in schools and in public. The colossal wage disparity between worker wages and CEOs in late-stage capitalism. Chinese bot farms, Russian plants. The fucking pandemic. All this was swirling in my head, not as a writer, but as a human.

So, I started a follow-up to my novel The Fountain, but wasn’t excited about the idea. I generated pages hoping to shake something loose. CUT TO: A shooting had happened at a show overseas and a dear friend of mine and fellow music lover—we’d attended a number of shows from stadiums to intimate clubs in Chicago—commented if we’d been in the area, that was a show we would have def attended. Music for us was church and for someone to turn that into slaughter…? Frankly, that comment seeded itself in a dark corner of my brain and grew like a fungus.

At some point in the writing process, a number of articles started popping up about social media moderators being diagnosed with PTSD from the horror they viewed. And then it clicked: in that setting I could explore all these issues on my mind. How would they cope? Why were they taking on such a horrific job? How could they support one another? What kind of relationship would blossom? What would they do off the clock?

Everything clicked and, like the man says, you gotta know when to fold ‘em, so I scrapped my initial idea (30K words for the writers keeping score) and set out to answer the questions surrounding this new premise. And of course, the answers are satirical—black humor as you pointed out, but it’s satire until it’s not. There’s no wink, no elbow nudge. And when no one was looking, I cultivated that fungus and transplanted it into this story.

The first draft downloaded from who knows where at all hours of the day and night. It was not fun (save for one section). It was soul draining and suffocating. But the material clicked. Connections flourished. Answers revealed themselves. That sounds woo-woo, but any writer will tell you some projects fire on all cylinders and some die on the side of the road. It was a bit of a gamble to embrace a world I was trying to compartmentalize. I could not find escapism in my writing as my characters were isolating while my family was doing the same during the pandemic.

It sucked.

Seriously, it was awful, and there were very real moments when I didn’t think I could finish the book. It was like putting on an old school diving suit, claustrophobic and stifling, and then plummeting from dark to darker. I credit encouraging words from Miette (my publisher) and my wife (also a writer) for pushing through.

When it was done, I felt it was worth it, and it worked. It may not be your cup of tea, but I knew theme- and story-wise it worked. And it felt risky, like something a younger me would have attempted.

CAVEAT: I also thought: no one is going to read this thing.

It’s too weird, it’s not traditional horror, thematic whiplash abounds with every turn, it reads quick, but gives you too much to digest. It’s somewhat cold by design, title is in [brackets] and all caps; how will you even Google it? Only one person has a traditional name. It’s structured like a five-act play. No one tries to pet the dog or save the cat early on. And, frankly, it’s a love story.

But at the end of the day, my publisher picked up this dark book and now a little more than six months later, we’re about to go into our second printing.

FUN FACT: I did a reading at the Berkeley bookfest and a person came up to me (didn’t buy a book, which is cool, but unusual for folks that get in line to engage), and they asked me if I had been a social media moderator and I said no. They complimented me on my research. Turns out they were formerly a mental health specialist at a big tech company for social media moderators. I understood why they didn’t buy a book. They knew worse things. (YET ANOTHER FUN FACT: the position received no training.)

Even at the novel’s end, the protagonist @Sa>ag3 doesn’t reveal his true name to @Jun1p3r, even though the two are the only characters in a committed relationship. What is going in the world of [NSFW] that discourages intimacy and honesty among people who are emotionally close to each other?

Two things: I wanted all the characters to be known only by their internet handles. This was, I thought, a novel idea, and fit for an ‘experimental’ novel of now. The fact that they are an in-person work family but still hiding behind the anonymity of the internet made me chuckle, but I can see a world in which that becomes the norm. This works for the group, but for the two lovers, it was a firewall for their traumatic pasts.

Intimacy for them is knowledge of the other before they met cute over beheading videos. They only get to know each other by their actions in the present. Their tacit agreement is their relationship will only be based on their shared history as it is created. It’s an attempt to keep their baggage in the trunk and not have it taint their relationship. There are a number of sex scenes in the book, none of them are titillating or particularly erotic, but it’s more spiritual, a way to purge and remain grounded. Copium. But of course, you can’t ignore your past, the cracks in their strategy start to form quickly. Like the Garden they create, knowledge eventually turns up to poison their world.

Welcome to love in the age of trauma.

FUN FACT: when I was writing the book, I reread all the dystopian classics, except for Brave New World, but my brain must have been working overtime as I didn’t remember the protagonist in that book is often called “Savage.” I found it fitting. And had I remembered that, I would have been tempted to change it. Glad I didn’t.

While the [NSFW]’s ending holds out a promise of hope for humanity, it seems to suggest that the only way out of a world—our world—that daily becomes more surveilled, monetized, and doxed is to burn it all down and start again. What do you think we are losing by living in such a system, and why are those who willing participate in such a system unwilling to disengage with it?

We are losing true connection and the ability to communicate, under the guise of greater connectivity in isolation. A younger generation would prefer to text than have a conversation. They face a greater social anxiety if someone calls or if they have to call and speak to someone. I was around when texting cost 10¢ / piece. It has its place (group threads, grocery store reminders), but if I feel a thread is becoming a complication, I stop texting and call.

Habit. Like the heat slowing being turned up. I’m always shocked when my phone usage is higher than I estimate. I try to be very intentional when I pick up my phone, but so much of modern life requires a smart phone. How else will they collect data?

But also remember when the lockdowns happened? Traffic plummeted. Air quality skyrocketed faster than they thought possible. Remember when WFH was tested and proved to be a more productive model? So, cracks in the system that exposed worker exploitation and we saw them. And we remembered.

But if you are invested in commercial real estate, however, you would argue for a return to the workplace. It’s about power and profit. They have gamified our lives to achieve the next high score.

My neighbor started a pop-up coffee shop in her driveway and I got to meet most of my other neighbors. We shared hopes, dream and fears and let me tell you, it was enlightening and invigorating. We are all not so different. But there’s no profit in peace.

It will be interesting to see what happens how we revert and grow when the Hack finally arrives and we are forced offline for a couple of weeks. No more bots. No more talking heads. An embrace of books and sit-down coffee and conversation.

Engineers will tell you robots and AI are supposed to be used for the three Ds, replacing jobs that are dirty, dull, and dangerous. Not writing homework papers or replacing artists or actors. It’s supposed to enable the pursuit of such.

Damn, where’d that soapbox come from…?

Concerning the Aquarist Easter egg chapter, apart from the repeated reference to the story in the novel as one that got the character Ray’s father into trouble with the Russian government when it was first published, are we to see Ray’s father, Ray Jr. with his typewriter, and @Sa>ag3 as dissidents in service to humanity rather than the system they are caught up in? Or was it more of a lark to create an Analog magazine-type action-and-hard-science SF story?

Ha! Great question. Both are correct. Ray Sr & Jr. are indeed dissidents with hidden agendas. As is @Sa>ag3, though his agenda is more personal than politically motivated. Despite their different mission statements as characters, both these hidden agendas dovetail nicely in the Live Feed Event set-piece.

That being said, I really wanted to see for myself why Ray Sr, an Afro-Russian Soviet era pulp sci-fi writer had his book banned and why he was thrown in the Gulag. I had to know. This is one thing I didn’t want left to the imagination. I needed to know.

So, I gave myself the challenge of writing the first chapter of the The Aquarist of Ganymede. No bells or whistles, just pure story; writing naked so to speak. I do love to play with form. And this was indeed a challenge as it had to reveal something new about the story and characters and elevate the pages that came before it.

(Also, I’m an OG Watchmen fan, and having this was my nod to Alan Moore’s Under the Hood excerpt.)

FUN FACT: I do thank the estate of Raymond Gunn Sr. for allowing me to reprint Chapter One. It’s BS, of course. I wrote it. A sci-fi scholar reached out to me at a convention and said he spent hours trying to find the Aquarist online. When I told him I had written it, he gave me a very friendly f*ck you. This pleased me.

And it gave me confidence style wise for my next book (see question #7).

What did you write the novel’s manuscript with—pen and paper, typewriter, or computer? A couple of the novel’s characters take to using a typewriter as a subtle form of protest it seems.

Every project is different, as I like to experiment with process as well. I do have about a dozen working vintage typewriters. I wrote most of another book on a typewriter, which I find very effective for story, but arduous to get those pages onto the computer for editing. I now have a vintage typewriter that is wired to jack into an iPad as a keyboard surrogate, and the kit to transform my favorite desktop typewriter, a ’21 Underwood No. 5. I love writing on that one.

[NSFW] was written almost entirely on a phone in the Notes App. At every hour of the day and night. All those bon mots were generated out of context and then layered in. It was a fever dream and I have little memory of writing it, but nightmares about editing it.

I’d originally planned for the book to be a mosaic told out of order (think Jenny Offill’s Dept of Speculation, which I love), but with the hashtags, bon mots, big voice/little voice layered in, I thought that might be a bridge too far, so it’s in chronological order (mostly), and it still baffles a number of readers. Others love the experience. Which, for me, as a writer is what I strive for.

My newest book was produced with 90% speech to text on my phone, after extensive outlining for each section. Then I edited on the laptop.

You introduce the novel’s sections—its nodes—with quotations from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Would you elaborate on what inspired your insight into linking Shelley’s “new Prometheus” with current-day social media?

It originally started as an idea about someone wanting to take different aspects of people a character had dated and combining them into the ‘perfect’ partner. Or that @Jun1p3r was going to attempt this in order to please @Sa>ag3. That idea quickly fell apart as I wanted @Jun1p3r to have her own agency and urgency.

But as I read more and more of Frankenstein, so much of it resonated with the main character as surrogates for the Creature (who like the depiction in Penny Dreadful, is quite eloquent) and the face as Victor. So, I used quotes as kind of a marker for each Node. Also, the bold green on the cover is a direct nod, as well.

What projects are you working on now or have slated for release soon?

Earlier this year, I edited a book of short stories for my publisher Whisk(e)y Tit by Anna Dickson James called Boys Buy Me Drinks to Watch Me Fall Down. My wife, a big shot screenwriter, was so taken with the collection, she asked to write the introduction. It’s delightful and raw and I can’t recommend it enough. It’s in pre-orders now from WhiskeyTit.com.

I’m currently a mentor with the SFWA [Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association] and a reader for the HWA [Horror Writers Association].

Meanwhile, I’m editing my new book and wool gathering for what will probably be a novella. The novel is called The Butcher of Nazareth and is horror-lit. It’s a retelling of the origin of Christ as seen through the eyes of an assassin. Think Citizen Kane meets Taxi Driver.I’ll be agent-shopping for that one.

Anything else I overlooked about the book that you want to emphasize?

[NSFW] is not a beach read. It rewards a close reading and reread. Also, if you like rabbit holes, there are plenty of things that appear only as a hashtag but are doors to jaw-dropping reads if you care to Wiki them, like the history of US government experiments on its own citizens. Gah.

FUN FACT: I’ve had people scoop up [NSFW] or reject it based solely on the trigger warning list: sex, drug use, witchcraft, profanity, gun violence, collapse, suicide, harm to a minor, terrorism, civil unrest, hate crime, social media, religion, capitalism, jellyfish.

It’s a good litmus test.

Also, don’t buy books from Amazon.