I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, ephemeral, small press, comics, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If you notice titles unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at:I arrogantly recommend…

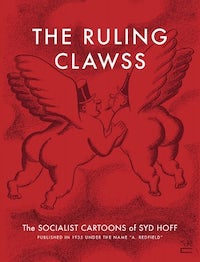

The Ruling Clawss: The Socialist Cartoons of Syd Hoff

The Ruling Clawss: The Socialist Cartoons of Syd Hoff

NYR Comics

Long before he wrote the enduring children’s book, Danny and the Dinosaur, and while he was developing a reputation among adult readers of The New Yorker, Syd Hoff wrote gag cartoons for leftist / communist publications like New Masses and Daily Worker (the American Communist Party’s official newspaper). In fact, his first book—this book—was published by the Communist Party, which collects cartoons he drew for the Daily Worker from 1933-1935—well before he was called up before Congress in 1952 to, Congress hoped, name names against fellow travelers from the time (which Hoff disingenuously declined to do).

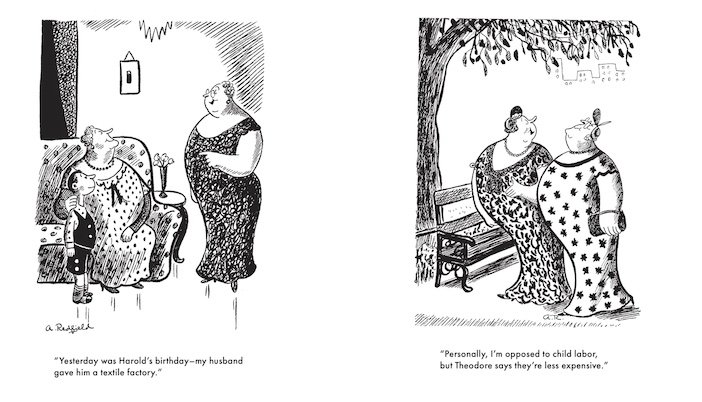

As the title, The Ruling Clawss, suggests, Hoff’s targets were the idle rich: Titans with enormous bellies (men) and bosoms (women) who remain insensitively oblivious both to the economic plight most people are forced to live within and the titans’ contributions to that plight. “Yesterday was Harold’s birthday—my husband gave him a textile factory,” says one matron to another in a moment of humble-brag, echoed in another exchange between two male executives: “Junior here wants to work himself up from the bottom of the ladder—he’s starting as vice-president.”

Among the wealthy are traits of anti-Semitism, racism, delight in massive layoffs and police brutality against workers. In this world, women are either morbidly obese matrons, or slinky secretaries / private whores to their bosses (“The requirements for this job are very simple—you will be a private secretary and—er—sort of—er—a companion”). The wealthy exploit wars to manufacture munitions for their own benefit yet are chary of aiding those mangled by them (About a vet who lost his legs in a war, a matron says, “Give him a nickel, sweetheart. After all, you made a couple million on the war.”) Food insecurity, the cost of living, and other basic creature comforts all people need are scorned by the wealthy as enticements to laziness among the poorer-off. It’s the sort of book you wish weren’t still so relevant nearly a century after its first publication. A must for Syd Hoff fans and collectors of political cartoons alike.

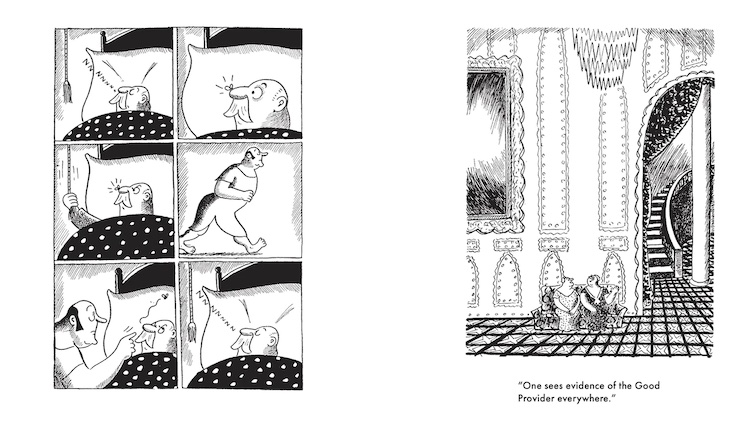

Horror and Huge Expenses: Stories

Horror and Huge Expenses: Stories

Robert Perišic / Will Firth

Sandorf Passage

Fiction writer and journalist Robert Periši?’s stories in Horror and Huge Expenses concern life in contemporary Croatia, including tales of suburban warfare fighting Serbians. Like many real Central Europeans, Periši?’s fictional characters live in a culture steeped in irony and ambivalence, where matters of marriage, religion, and ethnicity can take on potentially mortal consequences, depending on the whims of political (mis)fortunes. In this collection, one woman leaves a romantic get-away gone bad to visit her parents during a blackout in which homes are indiscriminately shelled, and yet finds plenty to laugh about. In another story, a young military man is almost knifed to death by a nurse as he tries to track down a friend who has left his unit, ostensibly to check into a drug rehab facility (where the knifing occurs) but in reality, to take a gig as a mason, instead. There are stories, too, that occur during peace time. In one, two women who meet occasionally over coffee accidentally discover another underlying reason for their friendship via the semi-coherent ramblings of a frequent caller to a crisis hotline. In another story, a hospitalized grandfather manages to get a few moments alone with his adoring grandson who doesn’t realize his grandfather is dying. Grandfather lets the boy know without letting the boy know. These and other tales of domestic life in a country filled with people living lives of quiet desperation are sympathetically and beautifully rendered.

The Gull Yettin

The Gull Yettin

Joe Kessler

NYR Comics

A 200-page+ graphic novel told without words about a young boy who is orphaned after his parents’ house burns down, rescued by Yettin, the gull—a mysterious figure who is mistakenly taken as a threat to the young boy and is brutally chased away by a woman who provides a haven for the boy. (Yettin eventually avenges the woman for the attack but at once immediately regrets the harm he has created.) The artist Joe Kessler has developed a distinct visual language for telling the story and is doing interesting things with narrative via pictures only. A fellow traveler that fans of American graphic novels may be familiar with is Dash Shaw, who also explores and pushes the realms of narrative and visual expression. The Gull Yettin makes for very nice work from an artist who bears paying attention to.

__________________________________________

Apastoral: A Mistopia

Apastoral: A Mistopia

Lee D. Thompson

corona/samizdat

Imagine a cross between Animal Farm, A Clockwork Orange, and Lord of the Flies, but funnier. The time is, presumably, near future—the world, its inhabitants, buildings and machines are similar to today’s, as are the bureaucratic morals, which in the case of Apastoral, allow for surgeries upon criminals newly convicted of committing capital offenses that place their brains into the bodies of various barnyard chattel—pigs, sheep, and cattle, mainly—since chattel are less expensive to maintain than prisons. (By the book’s end, the punishment has been extended to tax evaders.) The narrator, Bones, is transformed into a sheep after being wrongfully accused of murder during a jewelry store heist gone wrong.

Bones’s pals—Hog, Weasel, and Goose—keep the same names throughout—they’re gang members together (except when the threat of imprisonment looms), and gangs tend to give their members colorful names. This simplifies matters for readers once they’ve all had brain transplants but occasionally disorients as the narrative switches (frequently) from pre- to post-surgery settings. Society in general seems to approve of these new measures, initially, except for a few radical groups that are PETA-like in their aims—i.e., they are more outraged by what is being done to animals culled for brain transplants than they are the civil rights of criminals whose bodies are disposed of after surgery.

The transplanted human brains are joined to the more primitive part of animal brains to facilitate processing sensory input from the animals’ bodies. Human thoughts function largely as before, but if the animal’s sense of fear kicks in, it’s almost impossible for reasoning cogitation to regain control. This is no Mr Ed on a mass scale—the animals don’t talk, but human brains inside pigs (smart mammals) allow them to control their hooves well enough to scratch out words in the dirt. Nasty serial killers in human form become nasty killers in animal form, and without language or an ability to effectively communicate, organizing uprisings is well-nigh impossible. Escape is difficult; remaining inconspicuous once on the lam (sorry!) more so.

Lee Thompson’s thought experiment takes the program to its logical conclusions, minus little piggies going to market for consumption at home. What becomes of Bones, our anti-hero, is what this little gem sets out to explore.

Interview with Lee D. Thompson

What was your impetus in writing Apastoral—a particular outrage at prison reform, a random idea that seemed worth pursuing, or something else?

I feel like there was a problem to solve, for one: how to write a narrative from this ‘trapped-brain’ perspective, and I realized I could go in so many different directions, including some human-sheep hybrid language, which I decided against. I chose to tell it reasonably straight, with Bones being caught in the middle, a neutral character and madness on all sides. But yes, traps and imprisonment, injustice, the terror of that, of any fate rushing headlong at you. Also, I thought it would be fun to write.

In writing the story, how much was plotted out and how much was based on seeing where the premise led you?

I had a loose plot, which is how I write anything. Guideposts, some characters, a few themes and thoughts about how to tell it all. Enough to get me started and not feel too intimidated. The first page was written in 2009, and the majority in 2010, so I’ve forgotten much of the process. Plotting everything out would be the death of writing for me.

Apastoral won the 2022 New Brunswick Book Award for fiction—congratulations!—and yet is published by a Slovenian press. I assume this means no Canadian publisher was interested in your manuscript. What is the history behind trying to find a home for Apastoral?

I tried more than six and fewer than a dozen Canadian publishers, and one American press. Rejection is not wonderful so I’ve always tried to choose wisely when submitting anything. I had a previous novel get far with a respected Canadian press, then be rejected with insult from a middling Canadian press, then be accepted by an upstart Canadian press, which then went under. Yeah, this stuff messes with you. That novel remains unpublished and it looked like Apastoral was heading out to the same pasture until Corona\Samizdat appeared. Jeff Bursey, who had already published twice with C\S, vouched for my novel with Rick Harsch and a dozen years of sheepy silence ended.

You’ve just started a new press, Galleon Books, with one title out now and several more slated for the near future. What are the goals of your press, and how did you find out about the manuscripts you accepted?

The primary goal (but not sole goal) is to create a venue for authors in my home province (New Brunswick), which doesn’t really have an NB-focused literary press (Goose Lane Editions have a small fiction list). The goal is to give regional authors the chance to get their first book out, but also to publish some work that falls between the cracks – too short, too odd, too ‘unsellable.’ I suppose my own publishing struggles inspired much of that, but also that of writing friends and many of my editing clients. Manuscripts? I’ve been connected to the literary community here for quite some time now, so I solicited initially.

What are you working on now, regarding your own writing, and do you have any stories slated for upcoming publication?

I have a collection of longer stories that should be out with Corona\Samizdat late this year, perhaps next year. These I’ve written over the past ten years, and they’re thematically related. A mysterious psychologist named Dr. Shabazz. And I have the beginnings of an ambitious novel about a fictitious Arctic explorer, and madness, and many things Canadian.

The state of book publishing today seems to be odd—a handful of publishers control which books North Americans will see—but the most interesting works come from small publishers who can barely manage a toehold. How do you avoid burn-out and discouragement while working within a system that has less interest in literary merit than that which satisfies tastes for what is already known?

You find the right community of like-minded writers and readers! You lower your expectations of fame (wait: alter your expectations) and fortune, where selling 500 copies is a victory. The great thing about being with a small press is that you pretty much know who’s reading your book and you sometimes get very direct feedback. Who doesn’t love that? I have the same expectations with Galleon Books – get the work out, find some readers, build a little community. Grow.

__________________________________________

God For the Hills & Other Horrors

Jon Steffens

Filthy Loot

This slim book—two short stories and a novella—was my introduction to a subgenre of horror fiction called splatterpunk, itself influenced by the low-budget horror films released starting in the 1980s. Old-school horror and ghost stories often served up a moral: Evil deeds committed by restive spirits seeking vengeance for innocents harmed during life (or something similar), spirits who can only be quelled by some act of atonement by the living. Splatterpunk does away with the patina of morality to reveal a world haunted by unmotivated evil, or more accurately, motivated solely by the joy it reaps from harming others in a world in which all exits have been cut off.

Unlike traditional horror stories, frightening audiences is not an aim of the genre—it aims to disgust, instead. Thus, a reader’s place on the repulse-o-meter—ick on the low end, retching on the high—is a measure of a splatterpunk story’s success, reactions to, say, various bodily violations by creatures eldritch and unknowable, as Lovecraft might have it. That feature aside, a good storyteller of any genre knows to keep the descriptions concise and the plot constantly moving. And by those measures, Jon Steffens’s prose is a success: fast-paced, retch-worthy modern fables whose ideal telling place is a bonfire in a secluded camp, where ever creak, snap, and gust stokes the audience’s anxiety.

Rust Belt

Rust Belt

Sean Knickerbocker

Secret Acres

Sean Knickerbocker’s Rust Belt takes place somewhere in the Midwest, representing the region’s general downward mobility, shrinking population and job opportunities—a place where a person’s lack of trade skills or college degree amounts to economic suicide. The stories that comprise Rust Belt make for a sort of Dubliners in graphic novel form in that its characters represent who one might typically meet in such a place and the issues they face. In Rust Belt’s down-and-out Midwest, inhabitants live just above poverty level in trailer homes. Talented students are routinely bullied and receive inadequate schooling from dull-minded form-fillers. Marriages are empty of love and full of hate. And loud-mouthed right-wing scammers prey on loud-mouthed right-wing vloggers who succeed only bringing bad press to their employers while alienating their friends and neighbors. That bad news aside, Knickerbocker imbues his characters with traits one can sympathize and empathize with—they want to do well in a world indifferent to their fates, making them far more than straw men and women for the book’s argument that economic and social isolation act as powerful debilitating forces against the human spirit to thrive and love.

Night of Loveless Nights

Night of Loveless Nights

Robert Desnos / Lawrence Warsh

Winter Editions

In 1930, Robert Desnos published (in French) Night of Loveless Nights, a book-length moody meditation over his unrequited love for a singer named Yvonne George, who died a month before the book’s publication. Although Desnos is often affiliated with the surrealists, due to his early association with André Breton and his posse, the tone and attitude of Night puts me more in mind of Baudelaire and Nerval—decadent dissolution over a femme fatale described by metaphors more extravagant than surreal. Here is the opening description and invocation of the morbid night lying ahead of the reader:

Hideous night, putrid and glacial,

Night of disabled ghosts and rotting plants,

Incandescent night, flame and fire in the pits,

Shades of darkness without lightning, duplicity and lies.

Along the banks of a river whose fecundity masks its dangers, the narrator questions what he ever hoped to find in a love for a woman whose inner counterpart tormented him:

What destiny linked you to serve the most severe,

Those whose hair charmed the humming birds,

Whose hard breasts are a fatal refuge

And to whom the nape of the neck is a nest of mystery.

The loved one is a woman whose “eyes [are] without pity,” whose “beautiful mouth” is filled with “meat-eating teeth.” The narrator has a love-hate attitude toward his love who alternately pleases and frustrates him. What to do? The poem’s last line (“Revolt!”) reminds me of the ending of Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” “You must change your life,” and like it leaves unresolved how and by what means the revolt will occur.

This translation by the late poet Lewis Warsh first appeared 50 years ago in a very small edition. Winter Editions is to be commended for republishing this dark beauty.

The Story of a Paper Crown

The Story of a Paper Crown

Józef Czechowicz / Frank Garrett

Sublunary Editions

A recently discovered novella, written at age 19 by Czechowicz but published without a by-line nearly 100 years ago. The tale begins with the character Henryk’s botched suicide, presumably due to his “sinful” homosexuality, which others have found out about. (Czechowicz himself was openly gay in a culturally conservative Catholic nation.) Henryk drifts off in delirium after his suicide attempt. Ministered to by his sister and a priest, they hear him mumbling in his sleep, confessing love for a man while trying to shake off the affections he feels for a woman who also loves him. He loves her only as an idealized object, not amorously, yet still he feels drawn to her, even though he rejects the premise that men and women are meant to bear and raise children together. How Henryk will navigate his inner drive around the dictates of a culture hostility towards homosexuality is the issue he must work out.

Invisibility: A Manifesto

Invisibility: A Manifesto

Audrey Szasz

Amphetamine Sulfate

Audrey Szasz is the real deal: An intelligent, confident, and unsettling writer using a wildly unreliable narrator presented under her own name but with the addition of a doppelgänger named Nina—a high-priced, underaged call girl pimped by a woman referred to as Mother, described as one might imagine Jeffry Epstein’s girlfriend, Ghislaine Maxwell, to be. Mother keeps Nina under heavy sedation to keep her from minding the life she is subjected to—the sexual plaything of the wealthy and cruel. And the life she is subjected to has led to Nina’s emotionally dissociation from it and notions of morality and empathy. Her dissociation preserves her from killing herself. Other writers, such as Beryl Bainbridge and Helen DeWitt have hinted at the sadism of Britain’s wealthy, and Henning Mankell and Stieg Larsson have graphically described the sociopathy behind the staid respectability of Sweden’s fortunate ones, but Szasz deploys an unwilling accomplice to such crimes, ranging from acts of S&M to serial murders. It’s a lot to pack in under 50 pages, but Szasz does so deftly.

The Child and the River

The Child and the River

Henri Bosco / Joyce Zonana

NYRB Classics

A young boy named Pascalet, of indeterminate age, lives in rural southern France, near a river that rises and falls with the seasons. Until the time the story begins, he has been warned time and again by his parents to not stray from the house far enough to see the river. Until this point, he has only heard of the river and its dangers—swift currents, islands inhabited by Gypsies—but as the story begins, his courage and curiosity have grown to the point where he seeks an opportunity to see for himself. The opportunity comes when his parents leave home for two weeks, putting him in the care of his father’s aunt, who leaves him be during the day while she busies herself with her various household chores.

On his second trip to the river he sees its rough, rapid current, the dead trees it carries in its flow, some of which crash against an island in its midst—and discovers a boat, which he takes, and is carried along to the island, where he had seen small wisps of smoke rise in the air on his first trip, smoke indicating someone’s home or camp. Once on the island, he silently explores the area, where he discovers a hovel made from branches. It turns out to be a Gypsy camp where four men, a haggard old woman, and a young scrawny girl live, along with a bear. At night, the Gypsy men bring to the island a boy about Pascalet’s age, bound to a post and whipped, its lashes gashing his skin. After the Gypsies have bedded for the evening, Pascalet unties the boy, and the two leave the island with the Gypsies’ boat.

The boy who rescues Pascalet is named Gatzo, a terse but resourceful boy who can swim, fish, and make fires for cooking. The two boys bond immediately and set off on a 10-day adventure on the river, finding isolated, well-camouflaged coves to camp at. (The boys haven’t forgotten the Gypsies, who will need three days to repair the leaky boat Pascalet left behind.) The book becomes an idyllic adventure in which the boys rapture over the flora and fauna while living lives of simplicity and ease.

The boys’ idyl is interrupted one night when Pascalet discovers that Gatzo has disappeared. Pascalet takes a path inland, less to track down Gatzo—Pascalet has no idea which direction Gatzo took, whether on water or land—than to concede that his journey must now be at an end. Along his midnight walk he discovers a little village whose inhabitants have gathered to watch a marionette show. The marionette show is the linchpin to the remainder of the book, which ultimately describes a boy’s rite-of-passage into young adulthood, responsibility, and friendship. An excellent book well translated by Joyce Zonana.

Meth—DTF

Meth—DTF

SJXSJC (Shane Jesse Christmass)

Filthy Loot

An alternative but less titillating title for this novel could be Drugs and Sex (“DTF” = “down to fuck”). If it were a film, almost every sentence—even sentence fragments a la Burroughs’s cut-ups—would be a splice to a different scene. For example:

Cold spades digging up ancient bodies. Coffin lids discarded across Bel Air Estates. Houston as a post-industrial warzone—Samuel turns psychotic—his deep anxiety—gas station robberies and hideouts at movie theatres—the violent language of North America—minimum wage jobs in slow motion. I drive to Mexico to purchase McDonalds—parasites in some Gucci camping tent—this recession economy—drug blowout causes extreme blood pressure. A heavy smoker sits beneath some citrus trees—my defective skin pigmentation—cigarettes in my trouser pocket.

Almost every paragraph of this 150-page book describes a fractured delirium experienced by the nameless narrator and his boyfriend, Samuel, who crash on beaches and park benches, live in a series of decrepit apartments, spend their days and nights reeling from drugs and alcohol, find themselves in and out of hospitals, and see themselves as subjects of and witnesses to street violence—all without any sense of where the money comes from to finance this 24/7 debauchery. If this horrorscape is meant to illustrate a future dystopia (the book’s back cover proclaims, “I am a science fiction novel with no science fiction references”), then the future has arrived, minus climate change.

Vampyr: A Chronicle of Revenge

Vampyr: A Chronicle of Revenge

Louis Armand

Alienist (free PDF available at: https://alienistmanifesto.wordpress.com/publications/)

Fans of vampire lore take note: This book isn’t your undead dad’s vampire story. Instead, its vampyrs [sic] act more as anarchic forces unleashed during a time of plague—in this case, a disease labeled Corvid-69. (The book, in all its 500-page+ glory, was published in October 2020.) The main forces at work in Vampyr are Offensia (neé Rona Van Helsing, vampiric daughter of guitarist Eddie Van Helsing) and ŠVEJK (as in Jaroslav Hašek’s Good Soldier), which stands for “Solidarity, Vengeance, Emancipation, Justice [against] Kapital,” an anonymous, anarchic confederation and “one of the largest, most active & lethal military organisations in Mitteleuropa.” SVEJK’s opponents include @RealPresidentChloroqueen and #FakeNewMedia, run by Rupert Merdecock and located in Golemgrad, where much of the book’s chaotic action occurs.

Louis Armand is a novelist, artist, Joycean scholar, and political theorist who directs the Centre for Critical and Cultural Theory in the Philosophy Faculty of Charles University in Prague. Vampyr shows influences from such writers as William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, J.G. Ballard, and Thomas Pynchon while taking aim at such thinkers as the right-wing critic Julius Evola (Juulz Ebola) and Nick Land (Nyx gLand), best known outside of philosophy circles for accelerationism, which encourages the acceleration of cultural contradictions until society explodes and must start again from nothing. Vampyr is very much a theory-novel in which various contending ideas are put into action much in the way (although to different effect) Henry James claimed to set four characters in a room to see what happened.

Vampyr’s with thematic concerns regard capitalism as a dehumanizing force (rendered here as the “Corp[orate]=$[tate]”). (Note: Anti-capitalist does not necessarily equal pro-communist—each political system is prone to adopting fascist tactics to retain power. Don’t expect Armand to pick sides.) The story is presented via narration, technical documents, manifestoes, communiqués, photographic collages, and typographical effects. As a result, it has a high level of verbal and visual energy and, given the tight interplay between visual and verbal, could even be understood as a type of graphic novel, albeit one without hand-drawn graphics.

The world isn’t the imago of a spontaneous generation but a being cut in two. Thus the Manichaeism of the humxn [sic] produces the Manichaeism of the vampyr. To the lie of humxnity the vampyr responds w/ an equal lie. Wearing the old ideologies like a new pair of teeth, it bites the hand that feeds & the necks of all who supplicate. It’s the ghost in the dialectic, the struggle within the struggle, draped in a parody of flesh. It’s narcissism’s rapacious doppelgänger. The ontology of the negative. Darkness visible. A damsel’s cock.

Within SVEJK is a subset of radical women led by Offensia, “The Wild Grrlz” (which seem to be a nod to both Burroughs’s Wild Boys and the feminist art collective Riot Grrrl), “a fundamentalist organization devoted to gender=abolitionism & the destruction of the socalled ‘CisPatriarchal Corp[orate]=$[tate].”

It’s a wild ride. And, unless you want a hardcopy (my preference), you can download it for free from the publisher’s website.

[Read an interview with Louis Armand, writer, artist and critical theorist. ]

return self.new

return self.new

Aleš Cernák

Alienist (free PDF available at: https://alienistmanifesto.wordpress.com/2020/10/28/return-self-new/#more-1811)

return self.new combines essay, manifesto, and poetry into computer programming code, exploring, as Vít Bohal notes in the book’s preface, “the relationship between ritual (as a set protocol of symbolic actions) and machine algorithm (i.e. an automated sequence of computational tasks).” What this reduction does not allow for is the development and deployment of analogy, metaphor, and irony by the (literal or metaphorical) computer. ?ernák’s use of programming tropes is analogical / metaphorical but the “program” he writes cannot do the same—it only reduces the range of human possibilities, which is consistent with ?ernák’s inherent critique of a world-wide technological culture as one that largely serves to degrade humanity, a humanity desperately eager to conform its behaviors to computer capabilities. As the saying goes, “We shape our tools and then our tools shape us.”

Here is the fifth entry from return self.new on memory, history, and trauma:

Immediately after the authentic act of remembrance which terminates the drama of catastrophe and initiates the drama of the funeral, there comes the act of reflection.

The eye-witness confirms and reactivates the previous state.

If the indexing act is about

showing the dead – the ancestors –

and is iconic in that

the dead are projected as living by means of remembrance

this exposes the primal scene of memory

and provides testimony

of the transition from life to death

Whatever was before lies in ruins, only the survivor – the eye-witness – restores the fractured past

– begins to write history.

The prose and syntax are logical and suggest an eternal, unchanging recurrence—the fatalism of a form of reason hostile to contingency, evolution (for good or bad), and life as it is actually experienced by humans.

The Autodidacts

The Autodidacts

Thomas Kendall

Whiskey Tit

What if the love you thought you had to give was really only your own pain and suffering? And the place where you laid your love wasn’t a furnace for a consummation of a shared identity but the very blood of life poisoned by your existence in it? What if all your dreams of disappearance had taken on an essential misunderstanding and triumphed alongside it?

Do lies, obfuscations, and evasions of the past make its repetition inevitable? Is geography destiny? Thomas Kendall’s The Autodidacts makes the argument, à la Faulkner, that “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Involving the entwined fates of two families, told over the span of 16 years. Hovering over much of that span is a murder that may be a suicide and a stalker whose eventual whereabouts are never discovered. Infidelity, regret, denial, and more suicide haunt a pair of parents (from different marriages), their three children, and their children’s friends, all who live within visual distance of a lighthouse, the site of the original trauma that sets the story in motion.

Diane lives w/ Lawrence. She is mother to Henry and Jude. She is married but has long been separated from her husband, and lives with Lawrence. Lawrence was widowed by his wife, Helene, who had an affair with a man named James. Lawrence and Helene’s daughter, Evelyn, may be the offspring of James and Helene’s affair. Lawrence and Helene’s friend, Diane, has two sons, Henry and Jude. Diane’s marriage is loveless and she and her husband have separated. At some point after Helene’s death, Diane and Lawrence become lovers but live in separate houses. Evelyn, Henry, and Jude lead directionless lives almost entirely bereft of friendship, except for Henry, whose friend nicknamed Fiasco comes from an abusive, loveless home.

Whether love and friendship—and the conditions in which they are given and received—are enough to bring about salvation to these damaged souls is what Thomas Kendall explores. The comedic repartee between Henry and Fiasco during their formative teenage years provides a patina of relief sufficient to cover the profound grief that haunts their lives and fates.