Second Star and Other Reasons for Lingering

Second Star and Other Reasons for Lingering

Philippe Delerm / Jody Gladding

Archipelago Books

A collection of—what? prose poems, short-short stories, brief meditations, character sketches, nonmusical preludes?—miniatures devoted to capturing moments of subtle but emotionally intense sensations worthy of, well, lingering over. Here, for instance, is the end of the title story, about a couple of families that have made a long trip to spend the day at the beach:

They ran, they swam, they got out rackets, balls, magazines. The men took naps, their faces in the shade of the beach umbrella. The old woman especially kept an eye on the others, a half-smile of camaraderie on her lips, offering a cheek for wet, hurried, distracted kisses. Now it’s getting cooler. They huddle together, back to back. There are still apricots to eat. There are long silences. Yes, it was a lovely Sunday. Waiting for the last of the traffic to clear up at the Nantes bridge. Waiting, putting off tomorrow. Waiting for the dissipating joys to make way for the idea of happiness, which makes you shiver. It’s just the night falling, pull on a sweater. Being so very much together, when others seem so very far away, and when you’re all in a square protecting each other.

—Are you asleep Leila?

—No, I’m waiting for the second star.

Beautifully measured prose about nothing at all and everything important, limpidly translated by Jody Gladding.

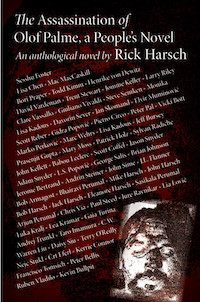

The Assassination of Olof Palme: An Anthological Novel, Vols. 1 & 2

The Assassination of Olof Palme: An Anthological Novel, Vols. 1 & 2

Rick Harsch

corona\samizdat

In my previous review of Volume 1 of The Assassination of Olof Palme, I noted that although the novel discontinuously veers from one set piece to another—true to its Menippean pedigree—a sense of overarching theme (moral outrage at military crimes committed in the name of nationalism) coheres the narrative’s various strands. Assassination’s anecdotes and digressions include long musings on suicide in Slovenia since the fall of the Soviet Empire; how the person who seems to be the primary narrator ended up crashing in a dead man’s apartment and assuming his name, Iztok Novak; justified rants against Nazis, Nixon, and North (Oliver); etc., ultimately culminating in (if not logically so) a wedding at which a table of multinationals, between conversations on the evil shenanigans of Eastern European leaders during WWI, engage in a farting competition, picaresque in the manner of Burroughs’s Naked Lunch.

Volume 2 of The Assassination of Olof Palme is also set in contemporary northern and Central Europe, beginning in medias res with an unnamed narrator, in a police station holding cell, giving a confession of sorts, about how he happened to be wherever he was when he was captured by the police now interrogating him, describing a period of abduction when he was ferried around the coasts of various northern European countries via foot, rail, and road, along with changes of clothing and visas—the last of which belong to Klaus Hauser, who assumed the identity of Iztok Novak in Volume 1. Hauser may also have a doppelganger in a different character (who seems to be from Algeria circa 1956 during its war of liberation from France), which ties together various thematic strands related to suicide and fascism, the fascism often abetted by democratic Western European and American forces, which in turn leads to an extended meditation on the death (too soon!) of Henry Kissinger.

Fascists of course believe in such notions a genetic superiority (and its corollary, euthanasia), and the drive to claim genetic superiority over the rest of humanity, leads to a plot to steal an ancient hand preserved in amber for the purposes of re-selling it to some other organization with power for “genetic” purposes, the sale of which will support a life of ease for the thieves.

If that weren’t enough, embedded into this novel, one of its constraints, was to seamlessly weave into the narrative contributions from several dozen authors—a formidable challenge achieved with seeming effortlessness.

Interview with Rick Harsch,

writer, editor, and publisher of corona/samizdat

Could you explain the process you used to create the “anthological” part of Olof Palme? How did you go about approaching the contributors, and did you give them any instructions regarding the theme, mood, or content of what they sent you? Did you sequence their contributions before you began the novel, or was there some way you manipulated what chance sent your way?

The process began with a feeling that Sesshu Foster, a very collaborative spirit, was perfect for writing the Heisenberg assassination plot, and then from there it seemed a nice way to write a novel. I was speaking with a guy from the Netherlands about the story of Vietnamese refugees washing up south of Chennai and once he agreed to participate, that was that.

Regarding the assignments, most of the instructions that might have been necessary were taken care of either by the choices of the writers or the assignment itself. For instance, one assignment was a memo and I ended up giving that to three people and got three nice paragraphs. Otherwise, I molded pieces to fit my needs where they strayed.

Are there two more volumes to come? In some places online, I’ve seen Volume 1 listed as the first of four. Volume 2 answered some of the narrative questions suggested by Volume 1 and then suggested a few of its own. Should I be happy with what there is, or will all be revealed in the fullness of time?

The book is finished. I was unsure about the number but the thought of asking anyone to buy four volumes determined that two would have to be enough. As you can see, the material is flexible, digressions potentially unlimited, but the end is the end (spoiler: the notion of writing a book in order to prevent the death of someone—Pinelli—seemed original, uniquely bathetic … or something like that.)

Assassination has a lot of funny moments, but the underlying current is one of outrage at military/political crimes committed by the U.S. in Europe and Latin America, and lives they destroyed, and governments they up-ended. Talking to those who live on the receiving end of U.S. policies seems to inform this novel, too. Did living abroad make you aware of even more debacles than Ronald Reagan and Oliver North’s covert actions during the ‘80s?

That’s a great question. I would like to say no, but when I think about it, the fundamental crime of the book—the ‘Gladio’ conspiracy—might never have come to my attention if I remained in the U.S. As far as I know only two serious books, one by an Italian historian and one by a Swiss, are the only books that have dealt with the crimes. That, and living in an ex-Yugoslav country has led to innumerable political/historical discussions and informed me in ways I can’t quantify.

How did you—as an America educated in Wisconsin—come to live in Slovenia and start a publishing house for authors writing in English? There seem to be a lot of steps between being, say, a guy who self-publishes his books he writes and a guy who says, yeah, I’ll do that plus seek out and publish books by other writers.

There are embedded misconceptions, at least by implication, in the question. For one, I came to Slovenia in 2001 as a published writer expecting my agent to guide my writing career onwards and upwards so that I could more or less live off my writing. It was nearly 20 years later that I started the press. I’ve gone into the agent disaster often enough, but suffice it to say I ended up having to work a lot on matters on the writing to feed myself, wife, and children, buy too much alcohol, and so on. It took a long time to get to writing again, with the exception of Adriatica Deserta, which I wrote when I suffered my first of several Slovene concussions and fractured some ribs and had to be in bed for a few weeks.

I’ve had one concussion in my life, about eight years ago, and that was enough. It took six months for my short-, mid-, and long-term memories to sort themselves out again. How did your concussions affect your writing? Were the concussions all related to the same activity?

You mean like banging my head against the wall in frustration? No. The first was a flying leap when I was running down a steep hill on a path that had three choices at the bottom. I went straight and that one had barbed wire strung between two trees: I flew a long way, broke ribs, was knocked out… That helped my writing, as I was in bed for three weeks and wrote Adriatica Deserta during that time. The next I was hit by a car while on a bike and the third was a bar fight I have no memory of but have been told an attack on me was unprovoked: I had my head rammed into a shelf/wall. That was the worst. My ear was partly torn off. I kept waking up and repeating myself (some hours maybe after the attack). Cops came and despite my bloodied state, did nothing, even left me there. People at the bar went through my phone until they reached someone willing to pick me up and take me to the hospital. That one was emotionally difficult to some degree, but if it has any effect, perhaps it is now as I fear the onset of dementia to the point that the narrator in my current effort writes from first person demential.

[Regarding starting corona/samizdat], I didn’t start the press with any clear plans in mind. I had two fat books that were going to be published by River Boat Books but were going nowhere (another story told enough elsewhere), so I borrowed money enough to publish the two books here as a sort of imprint of a press that had published a few of my books, mainly in Slovene. But to do that I need to come up with a name and that made this a press, and then it occurred to me that I could get David Vardeman into print, and as soon as I got the money to do that, I jumped around the apartment yelling about it, implemented the pocketbook plan, and the thing was done.

With the exception of Roberto Arlt, all the authors you publish are names new to me but who already have a trail of novels and stories behind them. I have Vardeman’s Angel of Sodom but haven’t yet read it. You publish several of his works. What do you enjoy about them?

Such questions are difficult. I think he has a knack for observing essentials about humans and concocting circumstances that allow for their banality to rise simultaneously to both the heights of absurdity and profundity at the same time.

What is Slovenia like as a market for books in English? Or is it largely an inexpensive base for printing and distributing books to North America?

Only Ljubljana has a market for books in English and the one independent store there has no interest in our books.

What moves you about story that makes you not just smile but say to yourself (some version of): “I didn’t just like the book; I bought the rights”?

I would like to be a cooperative witness, but the question doesn’t accurately describe our process. I have been very lucky to have veteran writers approach the press, or to spot great bits of writing that suggest a good writer is behind the deed, and I get suggestions from people. Or, as with Chandler Brossard, I get very lucky.

You’ve republished a couple of Brossard’s novels, with the help of his estate, and have been championing his works in general. Is it the social issues he deals with, how he deals with them, something(s) else?

Brossard is the most free author I have ever read. His brilliance is evident, but at the same time in Wake Up and Raging Joys he is also telling all of rational literary folk to fuck off, that no rules at all apply.

At whatever age you begin discovering the weird world of storytelling—the plot and characters, and the how the author worked the words to evoke whatever feeling s/he was going for—whose ideas and ways of telling stories impressed you the most and why?

First, Poe … then, in no evident order, Henry Miller, Celine, Rulfo, Onetti, Arlt, Conrad, Melville, Dostoevsky, Borges, Joyce, Beckett, Mutis…

I think it was writers who wrote darkly or desperately with poetry and/or philosophy, who wrote sentences that stuck with me … like illimitable gloom and so on … at night when I look at Boris’ goatee lying on the pillow, I get hysterical…

My gut recently suggested I pick up something by Louis Armand to read, at least as part of a bigger picture I think I’m beginning to see. Imagine my surprise when, to order a book by a member of Australia’s avant-garde community, I had to order from a publisher in Prague, where Armand teaches. My point: I sense that there is a community of writers in English, with deep knowledge across a wide swath of technical and aesthetic issues, who write formally challenging (but not alienating) novels that are also long—19th-century triple-decker novel long. And as exciting and excellent as much of this writing is, it seems yet still the level of self-publication and publication by small, shoe-string budget presses. Anyhow, the membership of this community I’m describing I guess would have birth dates somewhere between the mid-Fifties and the mid-Sixties, with the Modernists through Pynchon as influences, as well as the seedier side of pop culture. Oh, and they seem to be all men. Does any of this ring true, in terms of what you’re seeing too? If so, what do you think driving the ideology of the 250-page best seller?

Those I know in the business assure me that what you say is very true. And you might say white men, as well. But it is very deceptive. Not just because a few women have written such books but also because capitalism does not allow for artistic freedom, and, importantly, neither does the predominance of English. The current situation excludes innumerable great writers throughout the world, who will only be known if they get translated. And very few will be able to. It is a virtual miracle that we have heard of Arno Schmidt.

The 250-page best seller is a product of capitalism (oligarchy). Most authors of giant books have written enough 200-300-page novels as well, by the way. I think there is a broad range of shapes and sizes in DeLillo’s oeuvre, Coover’s … and there are those who fit your conception in every way but for length of novels (Curtis White, poets …). My last novel turned out to be 67 pages.

What are some great novels that remain untranslated into English, in your experience? Do you have some favorite Slovene authors you’ve discovered.

Vitomil Zupan’s Minuet for Guitar is amazing. It was published by Dalkey, I think, but I am checking whether it is still in print, and if not will do all possible to get it.

Publishing two writers from Colombia in Spanish has led to numerous conversations in which I have discovered there is yet a wealth of Spanish language novels available. English authors should be struggling to get published in Spanish.

Otherwise, I have no access to great unpublished works that I know of.

What is your writing routine like? How do you balance the responsibilities each of writing and publishing?

I’m 64 now, so lazier than ever. I balance life itself by doing as little literary work outside my personal reading and writing as possible. I enjoy nothing more than reading a book we published after we published it. All of Zach Tanner’s work fits that category of just figuring it is worth publishing, as did Stickley, Freedenberg, most of the Canadian novels and short stories. Surprisingly, I have read all of my own novels.

I have no routine any longer. The novel is always open, always in my head, but I am in no hurry. Now and then I consider picking up the pace and now and then I do. But there is no following novel yet, not in my head at least, so I guess that’s why I’m content. Oh, and I am working more on a film than anything else I’m doing.

Tell me about the film. What’s your role in its creation?

A former student is a film-crazed guy, and while we made an ad for corona\samizdat—The Gold Cactus—last year, it hit me that he needed to make a film but never would without a push, which meant an idea that was limited enough in scope to be feasible, so I began talking to him and he was eager and a friend on the Isle of Man was in on it and we just started making it. I’ve incorporated film into our organization so that I can legitimately use money to pay for the Isle of Man guy to fly in (soon a second and final time, to finish off the film more or less). So, I am an actor in the film. From here, we intend to seek funds independently to make a documentary based on my book about old Izola, which is the director’s idea. We’ve been very lucky with actors—it’s amazing how well people can act if they don’t have a script, just a notion, and let themselves simply be natural. In my own case, I can’t win: if a scene is good, people are apt to be dismissive: “That’s just you being yourself.” It’s been extremely satisfying, though, and I have learned a lot.

William Burroughs reportedly said in an interview that when he was deep into the act of writing, the experience was like taking dictation, as opposed to self-consciously making up a story. Do you have your own type of experience “in the zone”?

Eddie Vegas was that kind of mystical experience. I have no idea where it came from in any real traceable sense. Other novels have such moments always. I suppose that’s why I don’t re-write or edit much. What comes to me seems pre-ordained, however that sounds.

At several points throughout The Assassination we’re told that the narrative is strictly first-take—along the lines of Ginsburg’s “First thought, best thought,” I would guess? Assassination offers a kaleidoscope of narratives, including those involving assumed and changed identities. Do you work from a rough outline of incidents you want to cover, and improvise around that, or is you the end work entirely improvised?

In Olof I didn’t need a written outline, as I knew where it needed to go. The convergences at the end would occur regardless. Some fragments were probably revised and mistakes made while transferring them to the manuscript where typos were added. And some of the subconscious passages, the subversive muses taking over, were as carefully planned as anything in the book. But just as in this film, an idea that is seductive often leads to necessary future scenes, and that happened here and there in the book. For instance, the decision to use a character from a French Vietnam/Algeria book in my own.

Any chance you can talk about what you’re working on next, regarding your own writing?

The sacred current book? Talk about it? Curse it? Of course. The Odious Sea is a farce that takes place more or less in this time frame, maybe three or so years ahead, and the narrator is increasingly demential, a tactical decision because I can’t predict my own downward spiral. Each of 12 chapters is a play on a Herculean labor. So, for instance, I am on chapter four, the labor is the to capture the Erymanthean boar. In my book the main character is beset by the Everyman Bore. Chapter one involves the Nemean Lion. In my book the challenges is the Nemš?ian Lion S., which plays on Slovene for German, the root of Slovene for German coming from dumb, as in ba-ba-barbarian is said to have. So the book opens with all this coming together into my favorite opening, the narrator shouting through his dementials: “Potemkin!,” as an insane German artist is so involved in berating him she doesn’t realize she has released hold on her stroller and the baby is headed down enough steps that he will make it across the promenade to the sea … but he can only conjure the famous film scene, and suffice to say that he has to save the baby, though by the time he retrieves it it is dead, and in that chapter he has to rid himself of this grotesque woman.

_____________________________________________

Base / Zone

Base / Zone

DoubleBob

Frémok

DoubleBob is a cartoonist originally from Albi, France, with a line reminiscent of the fine-line work of C.F. and Carlos Gonzalez, with perhaps a tip of the hat to Anders Nilsen. DoubleBob’s frail-looking, faux naif technique rises to that of outsider art—something deeply personal and unique that is emotionally expressive but unconventionally so. Likewise, Base / Zone’s storyline is oblique and alien—so the reader is faced with a task much like de-coding a secret language, looking for repeating figures, rhythms, and motifs. DoubleBob’s concessions to conventional storytelling are our habits of reading left-to-right, top-to-bottom. Most of his characters look like some variation on human, the sparse vegetation is almost entirely down to the bark and leafless, the inorganic objects based on bizarre geometric shapes, and with frequent references to The Hanged Man card from the tarot. Very nice book in a small format, w/ fine lines and akin to cartoons by C.F. and Bonus points: The cover unfolds to a double-sided mini-poster.

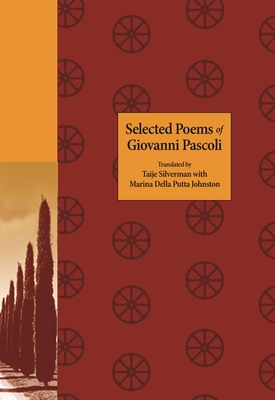

Selected Poems of Giovanni Pascoli

Selected Poems of Giovanni Pascoli

Taije Silverman with Marina Della Putta Johnston, trans.

Princeton University Press

Although the Italian poet Giovanni Pascoli (1855-192) influenced such internationally renowned poets as Umberto Saba, Edoardo Sanguineti, F. T. Marinetti, Cesare Pavese, and Pier Paolo Passolini, Pascoli is little-known in the English-speaking world. One hopes that Silverman and Johnston’s translations help to rectify that situation and bring an awareness of Pascoli’s excellent poetry to a larger audience.

Focusing on Italy’s flora and fauna, Pascoli was a naturalist of the lyric whose poems’ competing forces are yoked by sets of internal and slant rhymes and alliteration, embedded in lines of iambic measures; a poetic craftsman who makes it look easy—all ably conveyed by translators Taije Silverman and Marina Della Putta Johnston. Here’s a sample in its entirety, the poem “They’re Plowing”:

In the field, where vines gleam

the color of rust, and the morning fog

rises like smoke from the brush,

folks are plowing: one prods slow cows

with slow cries; others seed; with a hoe’s

patient blade one covers the furrow;

for the sly sparrow delights in the seeds

it sees from its branch on a mulberry tree;

the red robin, too—from bushes, its jingling

falls like the chime of gold coins.

Translator Tiaje Silverman provides an introduction to Pascoli and his work, a brief biographical chronology, and end notes on technical aspects of Pascoli’s poetry.

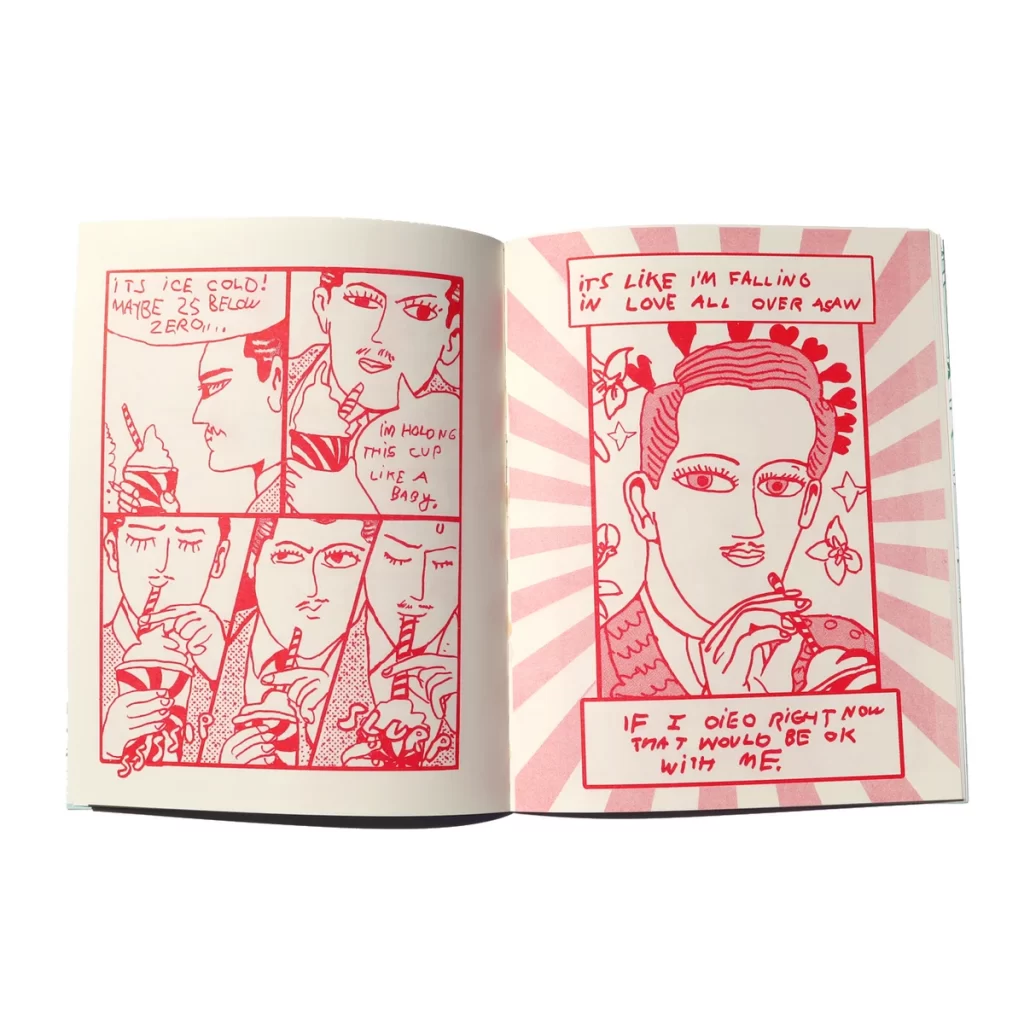

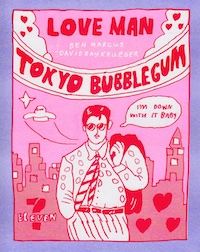

Love Man: Tokyo Bubblegum

Love Man: Tokyo Bubblegum

Ben Marcus and David Ray Krueger

Goodbye Press

David Krueger is an artist who works out of The Arts of Life , a center in Chicago devoted to cultivating the artistic talents of those with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Krueger met Ben Marcus at an outreach program that paired professional artists with those at The Arts of Life developing theirs. Love Man is an alien with a Slurpee fixation come to Earth to atone for mistakes from his past. The character of Love Man is Krueger’s idea and alter ego. Together, Marcus and Krueger develop a script and draw the pictures of Love Man engaging in acts of kindness, such as the following: Love Man bumps into Julia Roberts at the local 7-Eleven and offers her a Slurpee of his own concoction. She loves it and tells him so. “It came from my imagination,” Love Man responds, “I call it Tokyo Bubble Gum.”

As one might imagine, the two hit it off, and he takes her to the Italian Old Country Buffet for a romantic dinner, where he confesses the following:

Love Man: I don’t mean to scare you, but where I come from is like outer space, almost the next galaxy.

She: What are you trying to say. . . Are you married?

Will the acclaimed actress accept Love Man for who he is, or does only heartache lie ahead of him? Read Tokyo Bubblegum to find out.

(Note: This material also appears in Marcus and Kreuger’s anthology Forever and Ever Again—Collected Comics 2015-2020, from Perfectly Acceptable Press, and seems close to being out of print. I reviewed that anthology in this column a couple of years ago.)

Chaos, Crossing

Chaos, Crossing

Olivia Elias / Kareem James Abu-Zeid, trans.

World Poetry Books

courage is what it takes to

grow up & grow old when

the husk of skin offered

up at birth is a mark of subjection

—From “I Say Your Name”

Olivia Elias is a poet of the Palestinian diaspora, born in 1944 in Haifa but displaced four years later, first to Lebanon, where the French language was first imposed on her, then to Montréal at age 16. By the time her first book of poetry was published, in 2015, when Elias was 71 years old, she was living in Paris. As fellow poet and Palestinian Najwan Darwish points out in his introduction, both taking up the writing of poetry at such an age is unusual, as is the chance that it is any good. In the case of Elias, they are very good indeed.

Displacement, loss, memory, death, and yes, hope are factors people must face who have been evicted or forced to flee from their homelands, often on utterly inhumane grounds. Let the following sample represent the rest from this collection:

Sign Language II

These worn-out words

too precious for

a farewell with no return

you entrust them to the desert

at all hours

on all pages

you invent a language

of signs

yet no one ever

taught you science

forms on which to build

the Ideal City

what game are you playing

on the black-and-white chessboard

and what front lines are you moving

on the newsprint?

as for lack

and loss

they’ve been such intimate

part of you

that when you wearied

of yourself

they fell

like corpses at your feet

Soft Matter

Soft Matter

Lila Zemborain / Christopher Winks

Quantum Prose

The “soft matter” Lila Zemborain’s title refers to is the human brain, represented here as (with only two exceptions) a rectangular block of left-right justified text that fits on a single page. Zemborain’s blocks combine essay, poetics, philosophical meditation, and crônica (cf. Lispector’s journalism). The overriding concern with these pieces reminded me of Wallace Stevens, whose poetry was similarly concerned with human consciousness and modes of perception. The four plumb edges formed by the text marks out the edges of the consciousness in its container. Here is one of Zemborain’s untitled rectangles on one set of problems posed by our self-awareness:

I don’t know whether this is the structure that corresponds to the ages, but it’s the only one that adapts to a way of being. And so everything transpires in a coming-and-going that is foreign and grandiloquent, meek and mild, and age or circumstance, which will always be somehow adverse or sometimes friendly. Thank God love exits, if not, everything would be an atrocious devouring though maybe it is, ingesting the other in a benevolent or cruel manner, without any anecdotal and insistent middle ground. The edge between bodies exists and it’s real. Everything that goes beyond its limit invades the other’s limit, their permeability. But in turn, in order for the form to maintain itself, the equilibrium must be dynamic. The margins are minimal, a certain degree of temperature, a certain level of pressure, the elasticity of tissue, the level of light and dark, the tolerance of a certain volume, the ravages of the aromatic or repulsive in this organism which is what gives power to the self’s outbursts, its overflows. The mind is an overflowing of the body, capable of acknowledging that it knows what goes on in this rank of compression.

Castilian Blues

Castilian Blues

Antonio Gamoneda / Benito del Pliego & Andrés Fisher

Quantum Prose

Antonio Gamoneda is a Spanish poet whose first book, Sublevación inmóvil was published in 1960 but who found difficulty after that in having his works published during Franco fascist regime. From 1961 to 1966, Gamoneda wrote the poems that comprise Castilian Blues but was unable to publish it until 1982—seven years after Franco’s death—because it’s down & out tone was out of sync with Spain’s official party line, which was intolerant of any form of dissent, including statements indicating even a vague unease with what the nation had become.

Compounding Gamoneda’s problem of not toeing the party line was the fact that he was self-taught and lived and worked among blue-collar folk. He is a nonacademic who had to teach himself, for instance, what the English words meant to American blues songs by Blacks. He could feel the depths of emotion being expressed—what originally caught his attention—but not the specific meaning. Not creating just a Spanish-inflected blues poetry but one also deeply influenced by the 20th-century Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet (which arrived to Gamoneda via a French translation, which he could also feel but had to work through to understand), a poet of hope and an oft-jailed communist: Poetry of hope for the powerless and downtrodden, then, expressed in an accessible diction and simple style that his intended audience could related to and embrace. (Benito del Pliego and Andrés Fisher’s introduction provides a concise publishing history and sources of influence on Gamoneda’s poetry.)

Here’s an excerpt from “Questions Blues”:

For a while I’ve had the blues

because my words don’t enter your heart.

Many days I’ve had the blues

because your silence enters my heart. . .

All men love freedom so much.

Do you know how it is to live in front of a closed door?

I love freedom and I love you.

Do you know how it is to live in front of a closed face?

Gamoneda’s world is one in which ethical responsibilities are impinged upon by economic and political forces are opposed to something more liberal, expansive of rights, and humane—an oppression that warps even the responsibilities imposed by love. Here is “Love” in its entirety:

My way of loving you is simple:

I hold you tight

as if there were a bit of justice in my heart

and I could give it to you with my body.

When I mess up your hair

something pretty is formed in my hands.

And I barely know anymore. I only wish

to be in peace with you, and to be in peace

with an unknown duty

that sometimes weighs heavily in my heart.

Since 1987, when Gamoneda published in Spain Edad, his collected works to date, he won Spain’s National Poetry Award, and then in 2004 began winning national, transnational, and international (European) awards. Kudos, then, to translators del Pliego and Fisher for both their fine translations of Gamoneda’s poetry and bringing Gamoneda to an English-speaking audience for the first time.

C’est Mon Dada

C’est Mon Dada

Various artists

Red Fox Press

According to the publisher’s website, C’est Mon Dada is “A collection of small handmade artists’ books dedicated to experimental, concrete, visual poetry and asemic writing or any work combining text and image in the spirit of dada or fluxus.” The handful of books I read in this series includes contributors from around the world, including Julien Blaine, Anna Klos, Stephan Wagner, Michael Betancourt, and Stephen Nelson—each with his or her own book (40 pages), each presenting viewers with delightful interpretations of the elements of letter and font shapes (or, in the case of asemic writing, creating lines, whorls, and scratches reminiscent of writing but without semantic content). The small hardcover books (about 4” x 6”) are handsomely designed, well-made, and belong on the shelves of everyone who enjoys contemporary art and exploring the limits of traditional lines of communication, if you’ll forgive the pun.

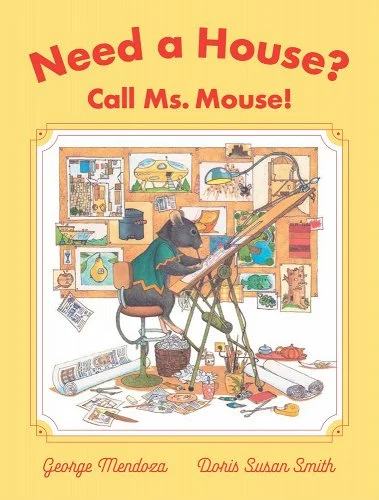

Need a House? Call Ms. Mouse!

Need a House? Call Ms. Mouse!

George Mendoza (story) and Doris Susan Smith (illustrator)

NYRB Children’s Collection

This picture book for children 4 to 8 presents imaginative floorplans to homes for 15 creatures—from the land, sky, and water—all designed, built, and decorated by Henrietta Mouse whose willingness to look the other way in considering her clients’ tastes and habits (a gaudy palace for the pig, a villa for a cat that would otherwise kill her) is an ideal of circumspect behavior under unseemly conditions.

Each creature’s home is shown in cross-section across a two-page spread. Trout, for example, requests a “palace to resemble the lost paradise of Atlantis”; Mole has designed for him a “clever staircase and trapdoor” that eliminates muddy floors in his house; and Rabbit’s warren has a living room with a bookcase, a landline phone, posters, and soft cushions. Several other animals also have book and LP collections. By and large (pig excepted), the critters have understated tastes as represented in the elegant-but-modest dwellings Ms. Mouse has created for them. A great exercise in playing pretend.

Fanticham’s Polazine

Fanticham’s Polazine

Francis Van Maele & Antic-Ham

Red Fox Press

Franticham is the duo of Francis Van Maele and Antic-Ham, two Polaroid enthusiasts whose imprint, Red Fox Press, also serves as a sales outlet for Polaroid cameras and films. Their thrice-yearly zine (“Hand assembled and stapled’; up to issue #20 now) takes up a different theme each issue (which range from 28 to 32 pages long), usually related to type of film or Polaroid camera used and experiments with past-date film. The zines I read (nos. 5, 11, and 17-20) covered pinhole photography, found mortuary pictures, girlie magazine images re-photographed with bad film, and so forth. In low-tech art, it’s a matter of imagination over budget, and in that Fanticham succeed. I don’t see evidence that they intervene in the Polaroids’ chemical production of images (which would be another avenue of exploration), but they do provide evidence of the wide range of the cameras’ aesthetic and emotional capabilities.