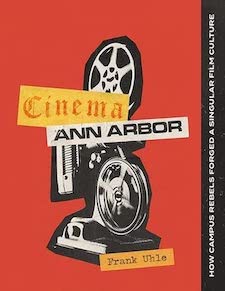

Cinema Ann Arbor is Frank Uhle’s love letter to Ann Arbor cinema, it’s film societies, and film culture exotica. The book is packed with surprising stories and little-known histories, including the Star Theater film riot of 1908, when a student was clubbed in the head and 2000 students arrived to protest, and Ann Arbor’s mayor called the National guard for help.

Cinema Ann Arbor is Frank Uhle’s love letter to Ann Arbor cinema, it’s film societies, and film culture exotica. The book is packed with surprising stories and little-known histories, including the Star Theater film riot of 1908, when a student was clubbed in the head and 2000 students arrived to protest, and Ann Arbor’s mayor called the National guard for help.

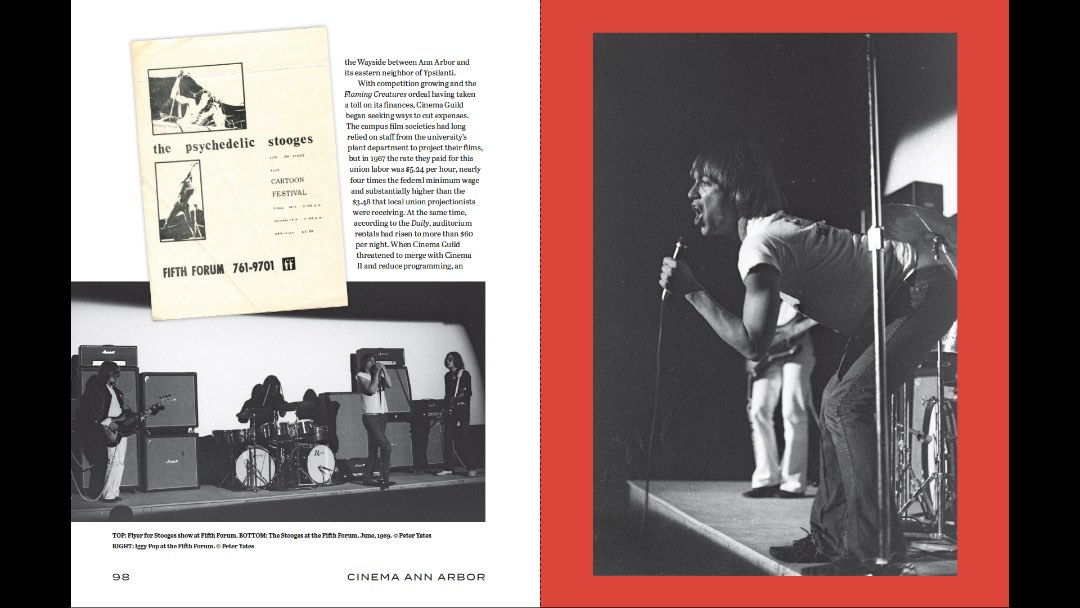

Cinema Ann Arbor covers the fabulous avant-garde collective ONCE group as well as an in-depth interview with Pat Olesko, the beloved six-foot tall Queen of the Film Festival and performance artist whose appearance and outrageous costumery became the official kick-off on opening night. There’s also a James Osterberg (Iggy Pop) story, who crashed the Velvet Undergound’s multi-media UP TIGHT performance and after-party at the 1966 Ann Arbor Film Festival.

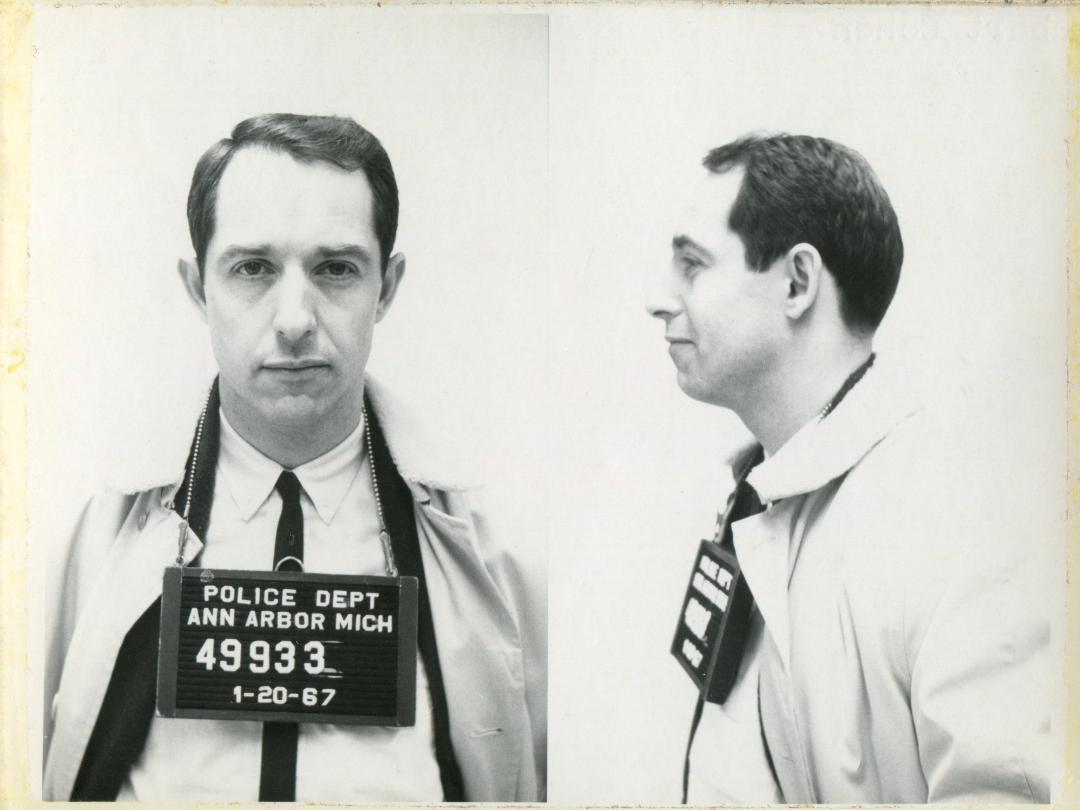

Cinema Ann Arbor covers the infamous 1968 film-bust and obscenity trial of Jack Smith’s underground camp-classic Flaming Creatures which made the national news, causing the arrest of University of Michigan professor Hugh Cohen and others. Flaming Creatures was screened by the Supreme Court who dropped the case.

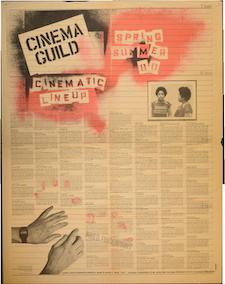

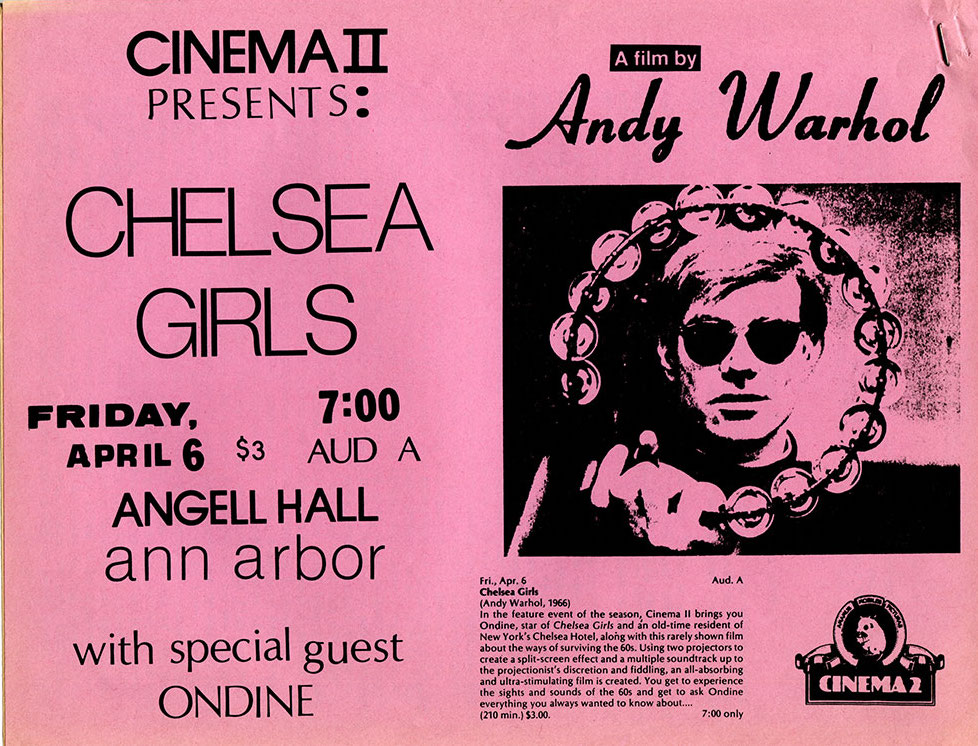

Cinema Ann Arbor includes Hollywood director visits by Frank Capra and Robert Altman, and gives strong detailed accounts of the campus film societies; Cinema 2, The Film Co-op, the Cinema Guild, Film Forum, and the historic Gothic Film Society that screened The Golem, Fantomas, The Passion of Joan of Arc, and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari all in 1949, and brought in Maya Deren to screen her films at the Rackham auditorium in 1955. The book’s 334 pages are packed with hundreds of photos, clippings, posters, and flyers-a visual feast and grassroots history for the film connoisseur and artist.

Cinema Ann Arbor includes Hollywood director visits by Frank Capra and Robert Altman, and gives strong detailed accounts of the campus film societies; Cinema 2, The Film Co-op, the Cinema Guild, Film Forum, and the historic Gothic Film Society that screened The Golem, Fantomas, The Passion of Joan of Arc, and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari all in 1949, and brought in Maya Deren to screen her films at the Rackham auditorium in 1955. The book’s 334 pages are packed with hundreds of photos, clippings, posters, and flyers-a visual feast and grassroots history for the film connoisseur and artist.

Signed copies of Cinema Ann Arbor are available in the Book Beat Galerie.

“Any film lover or history buff is gonna love this book, but the members of Ann Arbor’s Cinema Guilds and long standing film societies and all those people attending the Ann Arbor film festivals for all these years are gonna LOSE THEIR MINDS!” — Deborah Holdship, Listen In, Michigan, Michigan Today Episode 56

Frank Uhle will present Cinema Ann Arbor at Book Beat on Sunday June 25, at 3:00 pm.

Dreaming in the Dark: An Interview with Frank Uhle

What were some reasons that might explain how Ann Arbor became this avant-garde film hub for decades?

I think it was a combination of the right people, the right time period, and the relative isolation of Ann Arbor from Detroit, which led to the development of a distinct local scene. The population of the town is highly educated and has an interest in cultural offerings that might only be seen in larger cities, and one of the first student film societies in the country was started at the University of Michigan in 1932, which eventually became known as Cinema Guild. Along with bringing the latest art and foreign films to town, it began showing sometimes-controversial experimental films courtesy gay anarchist librarian Ed Weber, who delighted in tweaking the noses of the administration with titles like Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures, which in 1967 led to the arrests of four film society members.

Meanwhile, the avant garde composer Robert Ashley had grown up in Ann Arbor and went to New York to study music, where he met Massachusetts-born artist/filmmaker George Manupelli. They became close friends and collaborators, and when Ashley returned to Ann Arbor Manupelli joined him by getting a job teaching art at the University of Michigan. In 1961 Ashley helped start the ONCE festival to perform the work of local avant garde composers, and after it was a surprise hit ONCE expanded to include film, theater, and dance components, and also brought in guests like John Cage and Pauline Oliveros. In 1963 the Ann Arbor Film Festival was started by Manupelli as a spin-off, and it soon gained national recognition as one of the top experimental film festivals in the country. It would get submissions from filmmakers like Stan Brakhage, Yoko Ono, and Kenneth Anger, and hosted guests like Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground, who gave their first performance outside the East Coast in March, 1966.

So early on this town became a magnet for people from around the Midwest interested in film, and many folks I spoke with for the book mentioned coming to school here largely because of these totally extracurricular film events.

I was glad to see the ONCE festivals covered in your book and wondering if any film or photo documentation exists of Milton Cohen’s Space Theater?

Some amazing photos of it were published in the liner notes of New World records’ ONCE box set, which were taken by photographer Makepeace Uho Tsao. I am not aware of any films of the actual performances, however. I was very curious about the Space Theater myself and when I spoke to ONCE’s Joe Wehrer and Betty Johnson (who recently both just passed, sadly) I asked them “Was the Space Theater fun? Was it boring?” Joe thought it was quite interesting, but Betty thought it was boring! Joe’s description of it is in the book.

I never realized how connected the cinema groups were to classes being taught at the University. I thought they were independent and student run. You mention the racism of Birth of a Nation generating a boycott and was wondering if any other films had caused a student uprising?

While the university in fact gave the film groups no support whatsoever and even at one point was earning money by overcharging them for room rentals, their connections to the film program arose in part because several members who joined as grad students later ended up teaching film classes. But this also helped protect the societies a little bit when there were protests about their showing porn and other controversial fare, because these professors stood up for them. As for protests, there were multiple pickets at campus films over porn and the notorious Birth of a Nation. A particularly volatile one took place in 1973 when members of the Gay Liberation Front, most of whom were not students, took over the stage in Angell Hall to protest the stereotyped characterizations in the Hollywood film The Boys in the Band. There was a scuffle with audience members, and after the Ann Arbor Police came and got them to leave a bomb threat was called in. Another major protest by mostly outside groups came in 1986 when the rather unexceptional Jean-Luc Godard film Hail Mary was criticized by the pope. Quite a large number of Catholics, including some nuns, carried crosses and statues around Angell Hall to show their displeasure. This also led to a bomb threat, and when house manager Marlene Reiss was advised by the police not to shut it down, she decided to let the show go on.

Did you find any connections between film activities and the avant-garde shared between Detroit and Ann Arbor?

It seemed pretty minimal, though I do know that some folks who were involved in Detroit-area film societies joined ones in Ann Arbor, and there was also a guy named Mad Marvin Surowitz who showed underground films in the late ‘60s both in Detroit and at the Fifth Forum in Ann Arbor, which was a commercial art house. The underground filmmaking had some crossover, too, as Leni Sinclair moved to Ann Arbor from Detroit as part of Trans-Love Energies’ 1968 relocation, and I think completed her MC5 short film here. Probably the main connection was a group that called itself American Revolutionary Media, among other names. Like Sinclair’s organization, they had moved here from Detroit, and did some guerrilla theater, started a film society and a newspaper, and briefly ran a coffeehouse and later a bookstore. Their leader George De Pue was apparently an arch-enemy of John Sinclair’s since their days in Detroit, and they attacked each other in print from time to time. When the university discovered that the De Pue film society was not really a student group and was not paying its film or room rentals, it kicked them off campus. One later example was the Ann Arbor art/performance space Eyemediae, which had weekly avant garde film/video screenings and for a time in the mid-1980s duplicated its programming in Detroit at the Trumbull Street Playhouse.

Did you find any connection between European films and their influence on the film festival?

In the early years covered in the book the film festival primarily was programming the work of American and Canadian filmmakers, though I am sure there must have been some entries from overseas. But it seemed like the biggest influences were the New York and Bay Area experimental filmmaking scenes, as well as outliers like Richard Myers in Ohio. More of a foreign influence was visible in the Ann Arbor 8mm Film Festival, which the Ann Arbor Film Cooperative started in 1971 and which lasted til 1990. It was the first annual 8mm festival in the U.S., and became the biggest one in the country. In its last decade it frequently hosted films and filmmakers from around the world, and afterward the directors took programs of winning entries to Canada, Portugal, and Venezuela.

Another highlight of the book was your coverage of projectionist Peter Wilde, a behind-the-scenes projection artist—almost like a conductor interpreting a score. Could you talk about movie projection and your own background as a projectionist? Any highlights, catastrophic projections, or nitrate film encounters you may’ve encountered.

I became a projectionist right out of U-M art school – I was a member of Cinema II as an undergrad and knew Peter Wilde a little from his having shown some of our movies. After a year or so I got a summer gig out at the University Drive-In, which had 35mm projectors that were water-cooled and had big carbon-arc lamps that you fired up via a huge knife switch. I loved working there as we showed mostly exploitation fare like Night of the Living Dead and C.H.U.D. Over several decades of being a projectionist on and off campus there were definitely plenty of stressful film breakdowns and takeup reels that had to be turned by hand for 30 minutes after the belt broke. The most fun I ever had was definitely the night after the drive-in closed in 1985. A rascally projectionist friend, Dan Moray, suggested we all sneak back in with our keys to show some 35mm prints my friend Art Stephan had bought at a barn sale for $2 per reel. Though the drive-in’s manager was a moonlighting Ypsilanti police officer, I agreed to do this, and a half-dozen of us snuck in to watch mis-matched reels of films starring Elvis, John Wayne, and Sofia Loren, and even some mild B/W pornography. Because nobody was watching the entrance, several carloads of random people drove in and watched with us, and since the screen faced I-94 many more people could see the reels change from It Happened at the World’s Fair to The Green Berets. Of course my friend Dan Moray, who had pledged to take the heat if the policeman/manager showed up, never appeared!

Your bio also mentions you made 8mm films. What were those like?

I really wanted a Super 8 camera and in ninth grade managed to save enough money pumping gas to get one from the Sears catalog. We did the usual things most 8mm kids did like parodies of hit movies (The Sting became “The Stink,” i.e.) and a Godzilla-style monster rampage with my brother stepping on plastic models. One time I got ambitious and made a black-and-white sort of Bergmanesque film with more focus on camerawork, which I proudly showed to my high school German class, though our teacher got upset because it was mocking religion. The last movie I made was in college where I recruited my housemate and fellow Cinema II member John Sloss (who now produces films for people like Todd Haynes and Richard Linklater) and we taped over the trigger of the camera and played catch with it until the film ran out. Alas, I chickened out on entering it in the 8mm film festival, and seem to have lost it.

There’s been so many technological changes with filmmaking—could you speak about how these have affected film culture in Ann Arbor—and elsewhere?

The film societies existed to fill a need, which was to show repertory, independent, and experimental movies when there was no other way to see them besides projecting celluloid on a screen. The logistics of this prevented people from doing it on their own, and thus the societies acted as gatekeepers and curators. Ann Arbor’s scene, as described in the book, was one of the most vibrant in the U.S., and over time it brought many film fans to town, either as students or community members. But home video, VCRs, cable TV, etc. took most of this action underground, so you were no longer encountering the other film nuts out in public anymore and the camaraderie and energy of the film scene became somewhat obscured.

With digital projection and streaming, and all the new developments it has become even more fragmented as people have so much content to pick from that many focus on only one type of film, rather than delving into multiple genres and eras. Because the film societies took on an educational mission and it was just fun to see movies with an audience of strangers, I think more people in Ann Arbor used to come out to see the basic repertoire, ranging from Bogart and James Cagney to Kurosawa, Bergman, and the French New Wave. Now it seems harder to find younger people who have seen many of these core classics, which is something I hear from film professors, too. So I think, with some exceptions, that having access to almost any movie, all the time, has conversely made people less knowledgeable about cinema.

Cinema Ann Arbor was a labor of love—a passion project, that could’ve easily gone off track. I’m wondering if there were certain stories or chapters you regret leaving out due to research, space or time factors?

When I got going on the book I actually expanded from my original mission quite a bit, as I realized that including local experimental filmmakers and the Ann Arbor Film Festival were important sidelights to the film society history I set out to document. But because I wanted to tell the story of a bygone era with a distinct beginning, middle, and end, I only really reported on the first twenty years of the film festival, until George Manupelli left and it cut ties with Cinema Guild. So the festival’s later years, and the continuing story of people making films in and around Ann Arbor, are the two parts of the story that I had to leave out because I really wanted to focus on the film societies’ rise, heyday, and precipitous fall.

You point to the late 1980s as the beginning of the decline in film attendance. Why did the interest in film begin to change? Did the University also respond to this change?

Going to movies at the film societies was a hugely popular activity on campus up until the late 1980s. It functioned both as cheap entertainment for the greater student body (the societies typically charged half of what a commercial theater did) and as a film school for serious cineastes, of which there were enough to fill houses for anything from a new Werner Herzog feature to a night of experimental shorts. But as home video lured away more and more of the mainstream students and even the hardcore film fans who could rent obscure titles on tape, it quickly began to seem almost archaic. By 1995 the university’s most cutting edge, long-lived film group actually produced a handout titled “What Is the Ann Arbor Film Co-op?” to explain its purpose to students who then could barely be roused to come out for an in-person screening with Bruce Campbell.

Do you think a revival of film culture—back to the levels of the 60s or 70s is possible—why or why not?

It seems like a mixed bag – while there is a huge interest in watching movies, joined more now by streaming series, I do think that there has been a loss of interest in the importance of the deeper history of film out there. Certainly one can easily access the broad spectrum of world cinema and historical titles via services like Turner Classic Movies and the Criterion Channel, but it seems to have become more of a solitary activity. Even though the Michigan and State theaters program many interesting titles and there are several excellent U-M language department-sponsored series, these tend to draw an older film society-era crowd, and the community of film lovers that the societies brought together in Ann Arbor looks unlikely to be fully revived. I do think it can still exist in the larger cities, though, and I have been in touch with folks in LA and New York who talk about going to see all sorts of interesting stuff on screens with enthusiastic audiences. Given that films are generally made to be seen by an audience, I think that viewing them this way, at least part of the time, is a vital experience.

Ann Arbor Film Festival suggestions by Frank Uhle:

FOOTSIE by Pat Oleszko

GEMINI FIRE EXTENSION: a work by John Orentlicher — a film by Andrew Lugg, 1972