I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, ephemeral, small press, comics, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If you notice titles unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at:I arrogantly recommend…

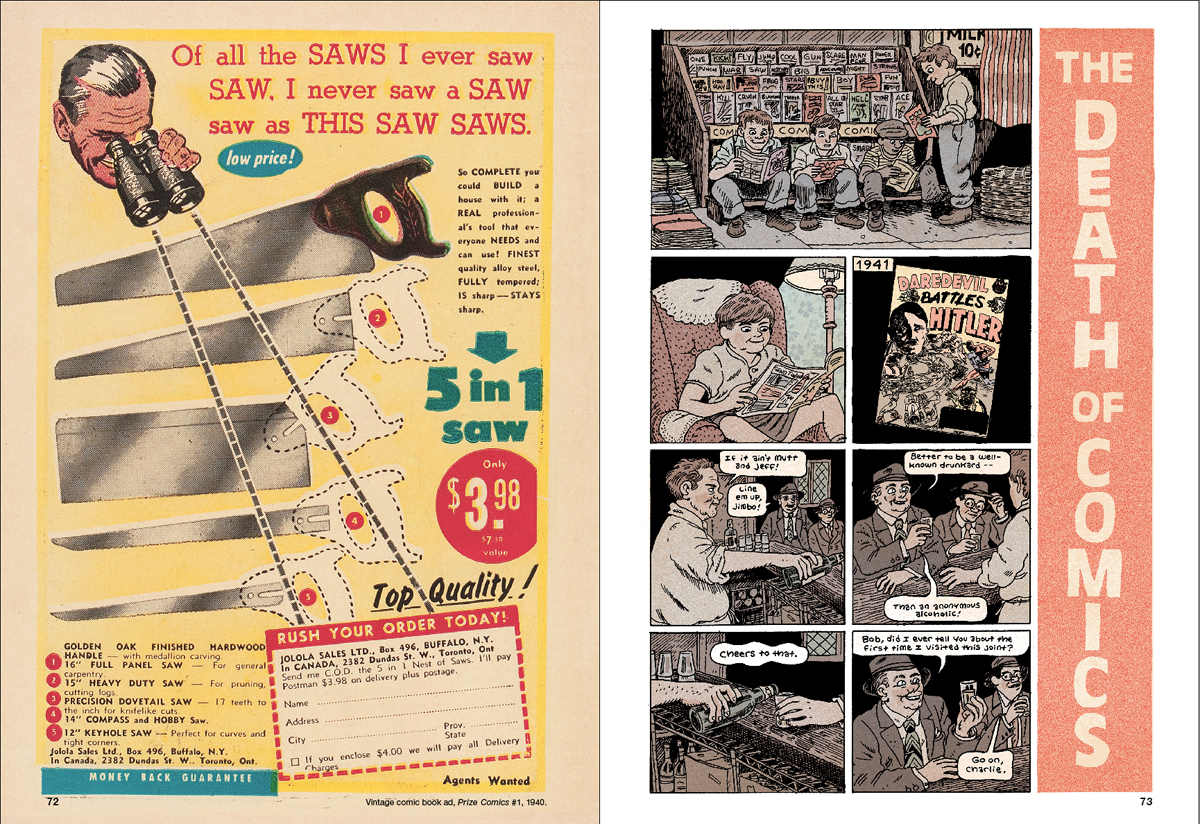

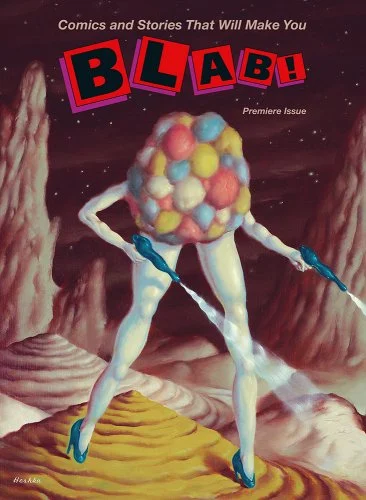

BLAB! #1

BLAB! #1

Monte Beauchamp (Ed.)

Dark Horse Comics / Yoe Books

Those who are already familiar with Monte Beauchamp’s anthology series when they see the phrase “Premiere Issue” added to the anthology’s title, BLAB!, may furrow their brows in puzzlement but this is indeed new material, and not a re-print of the out-of-print first issue. What’s new, too, are the publishers, Dark Horse and Yoe Books, whose support of Beauchamp’s efforts bodes well for more and more frequent installments. (See the interview with Beauchamp, below, on this topic.)

Anyhow. The new issue? Beautiful. In terms of editing, layout, sequencing, and design BLAB! Premier Issue represents Monte Beauchamp’s skills at their prime. For those unfamiliar with the BLAB! series, it has been a kind of Cabinet magazine for graphic designers—unexpected topics and reference illustrations, wide-ranging yet cohesive.

Every inch of this book is illustrated, including two different two-page endpaper pictures and a feature on Monster Magic Trading Cards for the end flaps. Over the years, the frequent presence of pictures by Ryan Heshka has made him as close to a house illustrator as BLAB! Between stories are full-page ads from old comic books—themselves exercises in old school low-budget/imagination/technical competence shilling. Editorially, the focus is on the first half of the 20th century, featuring two stories by Noah van Sciver (one on a cartoonist who started a cat craze about 80 years before B. Kliban), the other on a writer, during the ‘50s, of scandal-plagued crime comic books for kids, whose end became one of his own scripted stories.

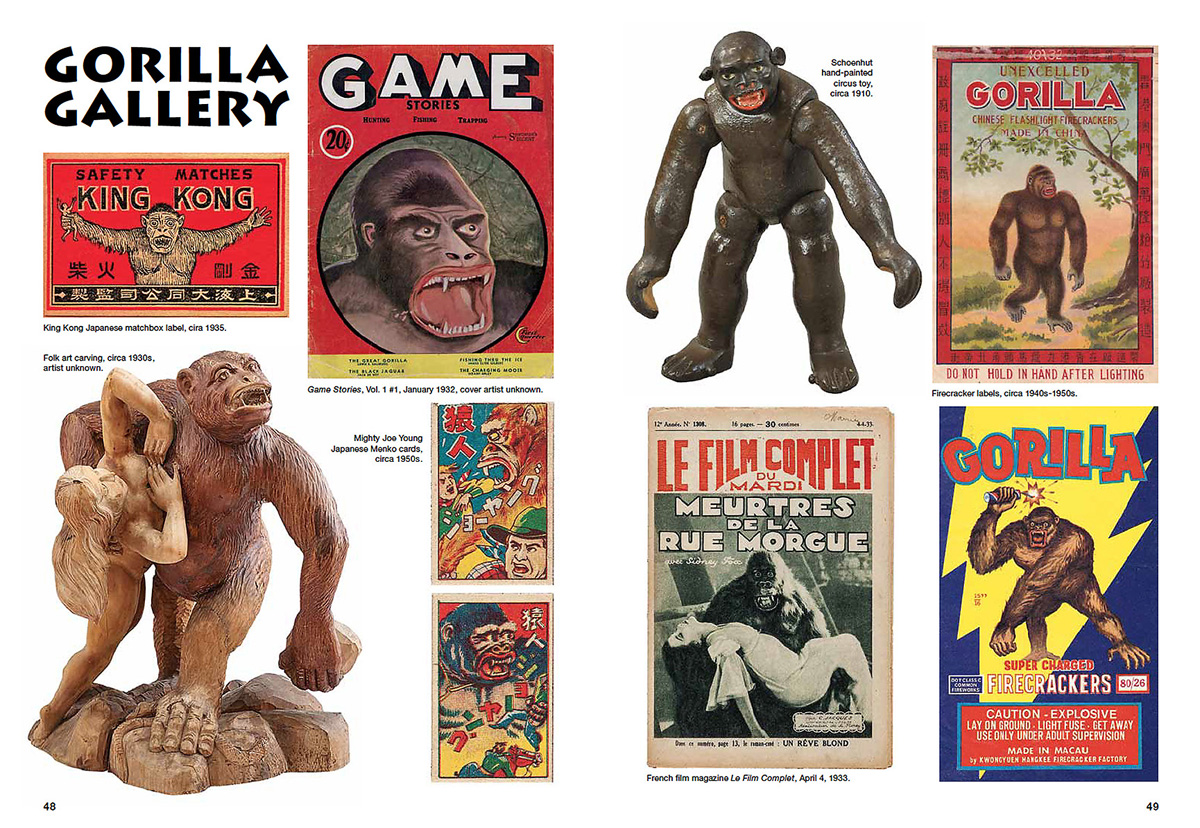

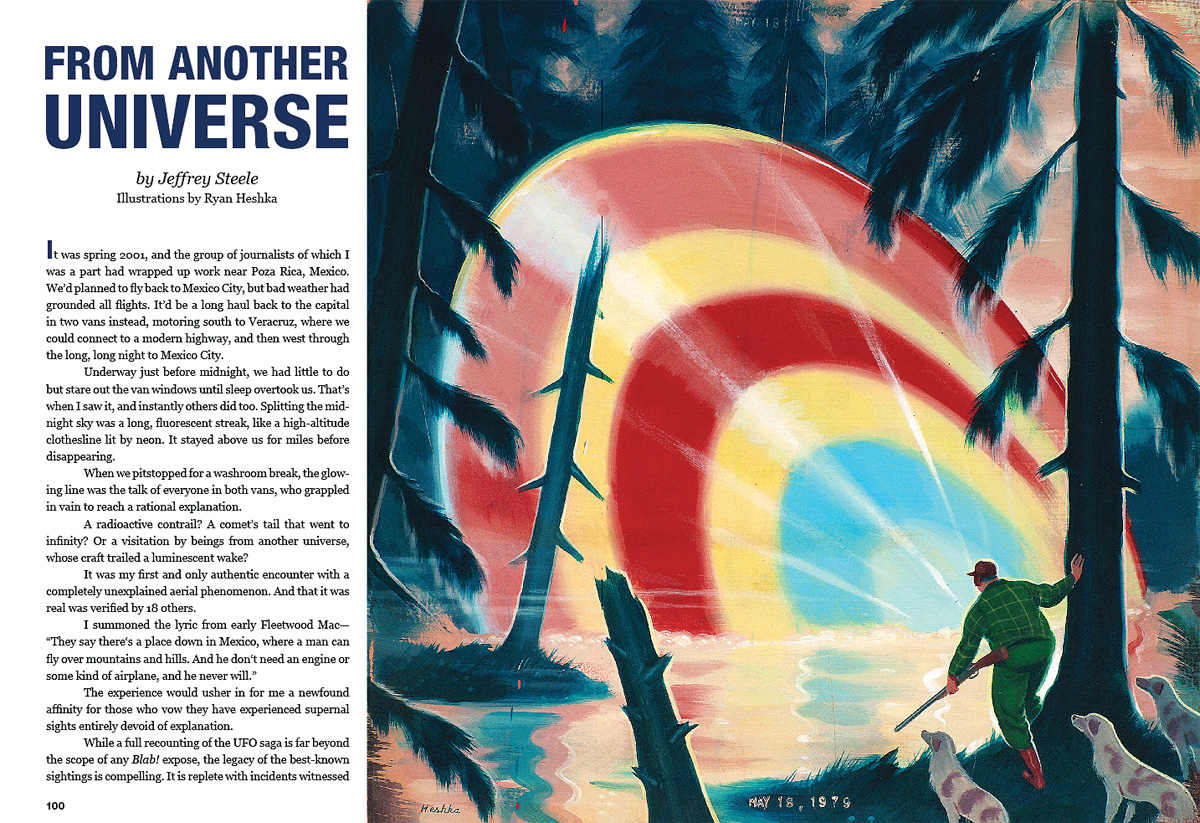

A long section on the gorilla in popular culture culminates with an old Fletcher Hanks strip about a mad scientist who sets out to take over the world with an army of gorillas he has injected with a secret formula. Posters for forgotten, obscure films about gorillas are presented, along with knickknackery such as firecracker wrappers and toys. (I don’t know if color adjustments had to be made for any of the old objects shown here, but the color reproduction throughout the book is excellent.) And where would a casual survey be of illustrated popular culture of the 20th century’s first half without ending on a feature (again illustrated by Heshka!) on UFOs?

Although the editorial concerns are old, BLAB! feels less like a trip down memory lane than an exercise in contemporary design as applied to older content. Whether a person is interested or not in the topics (I’m one who is), Beauchamp’s selection of older material—movie posters, toys, and other ephemeral—is a trove of older design and typographic sensibilities that shows the wide eye he employed in his capacity as an advertising director.

Interview with Monte Beauchamp

I think the first issue of BLAB! I bought was #11, with Mark Ryden’s painting of a butcher shop on the cover. If I had seen earlier issues of BLAB! before #11, Ryden’s cover made me break out my wallet at last—and do the same for as many past and future issues as I could. In addition to Ryden, BLAB! has also showcased Ryan Heshka, Gary Baseman, Kim Deitch, and others, including established and rising artists and articles on random but oddly fascinating topics. One constant among the wide variety of artists and styles you’ve published in BLAB! is the employment by artists of considerable technical skills in the service of absurdity, what’s become grouped as lowbrow Surrealism. The art, stories, and articles in each issue are wide ranging, but an overriding personal sensibility pervades each issue—they don’t feel like products of an editorial collective. What qualities do you look for in the works you select, and do you think your tastes have changed? (And if so, how?)

My past approach to BLAB! (the square-sized issues) was akin to that of a musical conductor. With each volume I strove to bring together a diverse group of talent to orchestrate an overall visual look that I was attempting to achieve. I sought out styles that fancied a particular element of art, for example texture, or contrast, or line, and so forth, in an attempt to present the look of each under one roof.

I formulated this approach when I reformatted BLAB! from a small black-and-white digest into a large square shape (10 x 10 inches) with interior color. I believe the influence behind all that was my day-time career as an advertising art director where I was able to implement a diverse roster of styles. With that particular run of BLAB! it was all about the visuals.

With the new BLAB! series, we’re story-focused. They’ll be new sequential art biographies and illustrated feature articles along the line of UFOS and gorillas, packaged in-between features of vintage ephemera. With BLAB!, I like mixing things up and I’m really jazzed about this new direction.

What influences do you think contributed to your eclectic tastes? What was is then about eclectic approaches that excited you, and has that motivation changed or evolved in some way since then?

I think life in general. As I age, my interest in visuals expands further and further. As a kid, I started with fossils from Midwestern streams, which led to the look of coins and stamps, and then to comic books. During the early square-sized issues of BLAB!, I was really into studying vintage ephemera such as matchbook covers, early postcards, and roller skate labels (from the forties and fifties). The techniques they were drawn in and their color blends inspired me to seek out similar styles in the editorial arena of illustration, and when I found such a style, I’d write the artist to see if they’d like to try their hand at making a comic strip (say, for example, Peter Hoey, who had never created a comic story before) or handling the illustration chores for a particular feature, such as A Case of the Shakes (written by Jeffrey Steele and illustrated by Jonathan Rosen for BLAB! #8).

I’d seek out fresh styles weekly at the magazine racks. In the pages of The New Yorker, I discovered the work of the french illustrator, Walter Minus, who became a regular contributor. In the pages of the art annual American Illustration, I discovered intriguing talent such as Christian Northeast, and Christian and Rob Clayton, who also became contributors.

As the square format continued, I became fixated on various aspects of Lowbrow art and Pop Surrealism movement taking place in California, and brought that look into BLAB!, which in 2005, led to THE BLAB! SHOW, an annual art exhibition I curate for The Copro Gallery at Bergamot Station in Santa Monica. This year marks our eighteenth show.

Now that the medium of magazines has been demolished by the convenience factor of internet technology, I’m really into the look of the early hand-held magazines such as the Vogue, Fortune, and the design work of Art Paul during the first decade of Playboy, where there was a lot of experimentation going on. So evolving BLAB! into a new magazine series and exploring that terrain has left me all jazzed-up for this new series. The irony of all this is none of it was planned. BLAB! started out as a one-shot fanzine and took on a life of itself. Change is the common denominator that has kept it rolling.

You’ve been putting together BLAB! anthologies since 1986. What process do you go through for each issue? Since years can go between issues, do you end up with stacks of things to look at when the time comes to assemble a gallery show and publish a book? And what compels you to continue producing these anthologies? The work of assembling, editing, and designing the anthologies is pretty much a solo act, isn’t it?

Well, first off, I’ve been fortunate enough to work with editors such as Craig Yoe at Yoe Books and Dark Horse, and Kim Thompson of Fantagraphics, and Denis Kitchen of Kitchen Sink Press, and Colin and Ron Turner of Last Gasp who have given me complete freedom to do what I think is best. So, there’s no creative blockage to begin with, which allows me to flow in the realm of creation. When, all is said and done, they know I’m going to do my very best.

Each issue usually starts with just a single inspiration and then develops from there. It’s an intuitive process. Once I get a sense of what direction the wind is blowing, I work with each artist to find a subject or topic they are interested in and once we both are on board with it, I cut them loose to go straight to finish. Along the way, some of them want my input; others don’t. Oftentimes, an issue gets started with a particular feature, say, of vintage material, and I’ll build around that. In many ways, creating a BLAB! is akin to writing a song … you get an inkling of an idea, pick up the guitar and get a sense for the song, and then you bring in the bass, the drums, piano, and lead guitar, and then you may top it with a harmonica, or mandolin, or the accordion. It’s a build, with an end result that hopefully delivers a particular feel.

The assemblage of BLAB! is a solo act. Handling the editorial, the design and art direction, the typesetting, the production led to long stretches of solitude, but along the way there have been professional and social gatherings over drinks with publishers, writers and artists, fans, and various contributors.

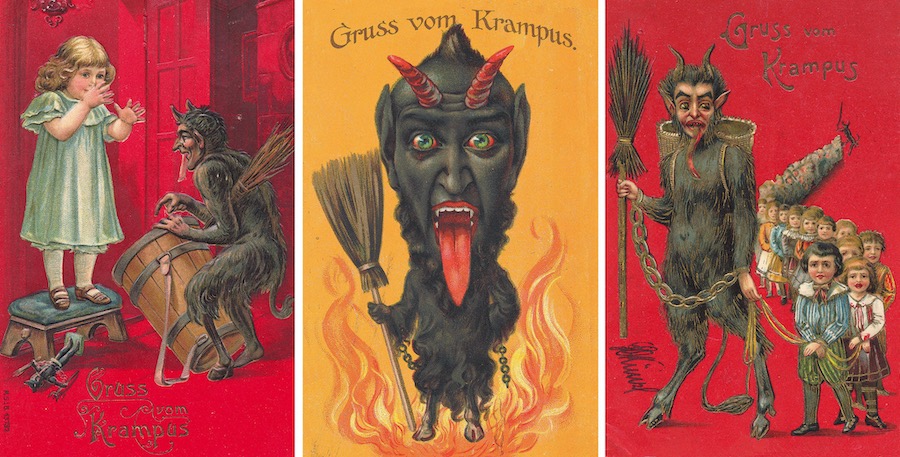

In addition to the BLAB! anthologies, you’ve edited books on matchbook cover art (Striking Images: Vintage Matchbook Cover Art, which is a lot of fun) and the more recent The Devil in Design: The Krampus Postcards. I think you single-handedly brought back interest this weird bit of Christmas history—I see Krampus-related stuff every year now. How did you discover this topic? Are you working now on another art-historical project?

A Chicago fan of BLAB!, who was also a collector of obscure ephemera, showed me some of the 100-year-old Krampus cards from his collection. I was enthralled with the various illustration and production techniques of those early cards and did a feature on them in BLAB! #11 and #12. And then set out to do a book showcasing the cards.

At first, it was hard to get any project with Krampus produced because none of the publishers knew what Krampus was. But those features in BLAB! did help and resulted in the publication of The Devil in Design: The Krampus Postcards, which resulted in representatives from tv shows such as NCIS, The Supernatural, and Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations knocking on my door. And from there, Krampus exploded onto the American landscape and resulted in my line of various Krampus merchandise products such as boxed sets of gift cards, sticker books, puzzles, playing cards, coloring book, and so forth, published by Last Gasp.

I also have other similar books in the pipeline, one of which is completed and unfortunately stuck in publishing limbo. I’m working on retrieving the rights back and will be shopping it around.

Will being published by Dark Horse allow you to produce BLAB! at a more regular rate?

Yes. Part of the deal with Craig and Dark Horse was to release an issue every nine months. I’m halfway through the second issue.

What do you think (or hope) BLAB!’s contribution to artists has been? To the general public?

You know, I really don’t think like that. The contributors and myself are focused on doing the very best we can and once an issue is released, then it’s on to the next issue.

But being that you asked, in regards to artists … I know that the publication is an inspiration to them based on the personal stories artists such as Emil Ferris, Ryan Heshka, and Mab Graves have shared with me. When, you’re operating in a vacuum, it feels really good to hear this feedback.

And then there are the young artist fans who are hoping to carve out a career for themselves in the world of art, comics, and illustrations. I’ve meet dozens of them who come to our BLAB! SHOWS to show me their work. And it’s a damn rewarding experience to see and feel their enthusiasm for art. It takes me back to the days when I was a beginner, and they help me remember that, for which I am continually grateful.

In regards to the general public, as long as they keep buying the BLAB!s, I’ll keep producing the BLAB!s. It’s a great feeling to know that my life has had a positive impact on others.

__________________________________________________

Whale

Whale

Cheon Myeong-kwan / Chi-Young Kim

Archipelago Books

Long-listed for the International Book Prize this year, Whale is Cheon Myeong-kwan’s first novel, a multi-generational story detailing the lives of three women—grandmother, mother, and daughter—from Korea’s lowest social class, demonstrating resilience, cleverness, and loyalty in the name of survival in a poor, rural, and heavily patriarchal society that has little but contempt for females.

Imbued with a sense of the mythical and archetypal—a sense of embodying eternal truths— Cheon endows his characters with extreme qualities (the most this, the least that, and something mysterious and transcendental in between (often sex and love), including the situations they find themselves in. The situations, too, often end up illustrating some eternal “law” regarding everything from physical to social mores. Thus, the novel’s actors seem as fatally flawed as any lead character in a play by Aeschylus. Most of Whale’s action follows the ups and downs of the middle woman, Geumbok, and her daughter, Chunhui.

Geumbok has a natural eye for efficiency, a skill she deftly employs with the menial workers she first takes up with. She’s a natural beauty possessed of a scent that drives men wild. Through sex and hard work, Geumbok is able to rise economically and socially. Her biggest break comes with an idea for a brickyard after meeting a man with an excellent sense of the materials needed for making excellent bricks. As her brick business booms, Geumbok applies her fortune to building a movie theater.

At some point during the years, Geumbok gives birth to Chunhui, a large, inordinately strong and ugly girl that Geumbok roundly ignores. Chunhui’s inability to speak and her slow ability to think leaves her almost entirely friendless and abandoned, even while her mother’s fortunes increase. In fact, Geumbok’s body eventually transforms into that of a man’s, and he (no longer she) has replaced “The strong, kind, confident woman she had been” with a “small-minded man, filled with selfish impulses and vengeful thoughts.” Having either betrayed, killed, or otherwise sold-out any friend or lover thye ever had, and having only ever ignored their child, Chunhui, what sort of fate could Geumbok possible face?

Chunhui lands in prison for a crime she didn’t commit and eventually returns to mother’s brickyard, which has been long abandoned, and lives on wild plants and animals, and manufacturing bricks again, just to pass the time. What point could there be in such a life? The answer suggests one reason this novel was nominated for a Booker Prize.

City of Torment

City of Torment

Daniela Hodrová / Véronique Firkusny & Elena Sokol

Jantar Publishing

Daniela Hodrová began writing what became City of Torment during the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia but was unable to officially publish until the fall of the Soviet Union and its puppet states. Consisting of three books originally published separately that together form a loosely connected trilogy, the entirety of City of Torment echoes with key events from the first volume, involving the fates of several families who live in an apartment building in Prague and the after-fates of several souls inhabiting the cemetery abutting the apartment building.

The effect is hallucinatory and, especially in the second volume, suffocating as local history endlessly repeats itself, varying only by person from novel to novel, who see echoes of the past all around them. Faulkner’s observation that “The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.” is developed to great length in this novel. As with the citizens of Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, the citizens of Hodrová’s Prague are sensitive to matters of ethnicity and religion. Thus, the Germans, Jews, and (Czech) Catholics of the apartment building form a synecdoche reflecting the larger Czech nation.

“Spiral” is a better than “circular” for describing the novel’s recurring actions, for as each generation adds new people, the spiral of recurring events expands to include more and more people historically interconnected. “But some of the dead see through all the layers of space and time. It’s enough for them to reminisce, and the place upon which they fix their gaze grows translucent and begins to transform.” As one character grows “translucent” s/he reminds the other characters of another person, then transforms into that other person at that other time—often “that other time” being when they were killed or committed suicide:

Is Mr Turek perhaps suggesting that those moments of Sofie’s languor, when her vision grows cloudy and the world spins before her eyes, are actually moments when someone else is emerging from within her? It is as such moments that Sofie Souslik attracts him the most.

That Czechs haven’t confronted their own anti-Semitism, even in light of the crimes of WWII, is alluded to by the frequently mentioned “Jewish kilns,” “ashy remains” that sometimes on windy days clings to the characters and their clothing of the novel’s characters whose are alluded to frequently in this book. (The Nazi concentration camp in Terezin is about a 45-minute drive from Prague.)

In its third part, City of Torment becomes meta, and our new narrator, allegedly Daniela Hodrová herself, discusses the events of the first two volumes while telling us what and who her original sources really were. But because the actions, their perpetrators and places of occurrence seemingly amount to an endless set of small variations on a theme, their actions (and the novel) feel static. Hodrová is a well-regarded author and scholar in Europe, which some of her works winning prizes. I’m willing to see my reaction to City of Torment as a minority of one, so I don’t mean to discourage other curious souls from trying this novel. It just didn’t work for me.

A Very Old Man

A Very Old Man

Italo Svevo / Frederika Randall

NYRB Classics

Italo Svevo (1861-1928; born Aron Ettore Schmitz) was a novelist from Trieste condemned to a day job with his father-in-law manufacturing paint for ships. In his early 30s, he self-published two novels—A Life and As a Man Grows Older—which were, on the whole, roundly ignored. A couple of reviewers went out of their way to pan them. At that point, he gave up writing. (Or so he told his family. I’ve read at least one account that claims he continued writing simple fables, one a day.) Twenty or so years later, the painting business picked up clients in Britain, and Svevo decided to improve his English by hiring a tutor—specifically, a young Irishman, about 25 years old, who recently moved to Trieste to teach English, James Joyce. Joyce—who once sneered at Proust for lacking discernible talent—came to discover Svevo’s earlier writings and praised them—a move Svevo was prepared to ignore as a kindness bestowed by someone receiving money from him, until Joyce began reciting pages of Svevo’s novels from memory.

Boldened, inspired, and made confident again by Joyce’s praise, Svevo cranked out Zeno’s Conscience, which was then published by one of Joyce’s friends (was it Ezra Pound?), and which received boundless praise from Europe’s top literary folk. Svevo’s joy at the attention was cut short when his chauffeur crashed their car into a tree, which precipitated the heart attack that killed Svevo. Now, finally (95 years after Svevo’s death!), Svevo’s notes for a sequel to Zeno’s Conscience have been published, key scenes less the connective tissue, and with a few narrative inconsistencies. Frederika Randall’s translation manages to capture the infinite variety of Zeno’s self-delusions, from being forced out of the business he’s spent his entire adult life doing, to being a grandfather and (briefly) a mistress-keeper.

Part of Zeno’s charm is his recognition of his own flagrant hypocrisies in situations with bad outcomes where he can defer rightful blame from himself—with varying degrees of plausibility and self-delusion—to others. In lieu of then shaming those upon whom he has cast blame, he offers pity and a sense of moral example for his ability to forgive. Telling the unadorned truth doesn’t come naturally to Zeno—it seems to bare to be truthful. Some of his rationale is spelled out in his reaction to tales of womanizing told to him by his nephew Carlo, who is a cardiologist:

He [Carlo] boasts of his adventures, and his boasts are so cheerful I can’t help but enjoy them. Maybe I’ve been slightly dishonest, in that I exaggerate a bit. Not much, though, and not often. Only about the number of women. But I do exaggerate their attributes, yes. Although I never went so far as to boast of any princesses. There was one that I spoke of as a duchess so as not to confess she was the wife of a commendatore. I guess I could have said she was the wife of a cavaliere without being indiscreet, but I didn’t. I wanted to appear important to Carlo, and besides, being honest made me feel so good that I imagined exaggerating I was being even more honest. Maybe it was a way of finding out what I might have done, if others had let me. A confession more honest than mere confession.

When the First World War ended, so did many former business laws, taxes, and terms of deal-making; likewise, social culture allowed women more freedoms. While the new business pace confuses Zeno, he finds only inconvenience in his daughter Antonia’s refusal to modernize:

Antonia was dead set against the freedoms permitted to young ladies after the war. Not only wasn’t she interested in dancing, she wouldn’t leave the house by herself. She had to be accompanied everywhere by her mother or one of the maids, and the assignment of these duties was a real domestic problem, given the amount of surveillance she condemned us to. Sometimes even I had to leave home in the evening to take her somewhere, or fetch her. She was like a small bale of goods that could only be moved by a shipping agent.

In Zeno’s hands, the traditional act of chaperoning as a sign parental love, protection, oversight, and concern for a daughter’s reputation becomes a tedious act of needless surveillance. Rather than increase the daughter’s moral value, chaperoning only affects her market value and thus her ability to be off-loaded from one household to another, which doesn’t concern him much.

But it’s not as if Zeno’s household awaits his opinions with bated breath. When Bigioni, a suitor for his recently-widowed daughter’s hand, asks Zeno for his support, Zeno realizes that he—Zeno—has no influence over his own household. On the contrary, Zeno’s support of Bigioni would only push Bigioni further from his daughter—and from his son Alfio, whom Bigioni is also unsuccessfully trying to befriend. Only the eternally patient Augusta, Zeno’s wife, can put up with his typically male attempts at self-importance, a male self-importance that often reflects itself in ignoring what others say to him, including his old friend Misceli, who likewise ignores Zeno:

By now Misceli had moved on to quite different topics: stock market affairs about which he seemingly knew a great deal. He looked hot and somewhat distracted. As if, when he talked, he never listened to what he was saying. Like me, who also didn’t listen, but only stared at him, trying to determine what he wasn’t saying.

For a guy reading this, at least, it’s comically dismaying how many of my own attributes I can find in Zeno. Everything by Italo Svevo comes highly recommended.

The Sack of Detroit: General Motors and the End of American Enterprise

The Sack of Detroit: General Motors and the End of American Enterprise

Kenneth Whyte

Knopf

Kenneth Whyte’s study of the factors leading to the decline of Detroit’s automobile manufacturing prowess—General Motors’s in particular—begins in 1958, when the U.S. entered a recession and car sales tanked. Most cars out of Detroit at the time were large (nearly 18 feet long and 3,000 pounds heavy) but the import market—small cars out of Europe, where streets were narrow, gas cheap, and incomes smaller than Americans’—was beginning to grow. Also, at the time, over 30,000 traffic fatalities were occurring each year, eventually rising to over 50,000 deaths a year deaths per year, despite efforts to educate drivers via licensing and engineering better roads.

Ed Cole, an engineering and management prodigy at GM, decided to provide the American public with an American car that could compete head-on with the nascent import / compact market, arrived at the Corvair, a car which offered numerous innovative features, the most significant of which for consumers were its compactness and low price. In 1960, when Chevrolet introduced the Corvair, Ford and Chrysler also introduced compact cars.

Sales of the new cars ended a four-year slump for the American automakers at the expense of foreign-made compacts. Until 1960, sales of foreign-built autos had been roughly doubling each year. Buoyed by this success, Detroit automakers began buying up foreign automakers, largely in Europe, to compete on a global scale.

Beginning with the recession of 1958, during Eisenhower’s second administration, the auto industry’s long honeymoon with the Federal government was over, and overt hostilities against the industry were taken up by John F. Kennedy, who had little interest in business leaders and found them all to be crooks at heart.

Enter Ralph Nader. Nader’s attacks on the auto industry’s lack of focus on consumer safety didn’t come from nowhere. Concerns about auto safety had already been raised by a small number of people—doctors and lawyers, mainly—who began studying traffic-accident data to determine what the safety issues were and how they might be addressed via better engineered car interiors, interiors that tended to damage the bodies inside them.

Starting in the late 1950s, consumer advocacy groups (a new phenomenon) began demanding higher quality products from manufacturers in general. Although people placed in Washington, DC—such as Ralph Nadar and Daniel Patrick Moynahan—were researching traffic accident reports for evidence of careless auto manufacturing, Senate hearings that included testimony from the upper echelons of the Big Three auto makers demonstrated that automakers had been incorporating safety features into their cars—seat belts, a rear-view mirror, door locks that kept doors shut even upon impact, power steering, and so forth. Despite those improvements, death rates from crashes remained alarmingly high.

Although not addressed by Whyte, the discrepancy between adding safety features and consumers using them seemed to owe to consumers who assumed that the cars they bought were already safe. Safety was a term consumers didn’t seem to define for themselves until after an accident occurred. And because consumers assumed cars were already safe, they took a passive view of their own needs to protect themselves once inside the cars, including the need to perform routine maintenance on them. (By the early 60s, when automakers were installing seatbelts that drivers were not then legally required to use, only 7% of drivers strapped in. Furthermore, traffic accident analyses from the time placed the blame for over 90% of accidents on poor driver performance, including driving on bald tires, driving with worn brake pads, driving under the influence, and so forth.)

Flustered by attacks on Ed Cole’s Corvair from the government and media outlets, on the one hand, and brisk sales of Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed (Nader’s screed against the Corvair), on the other, GM ordered a grey-area background check on this guy Ralph Nadar, who seemed to have no discernible financial support for his relentless denunciations of the auto industry. The Goliath GM hiring private dicks to harass a lone David outraged public opinion when GM’s investigation came to light.

The automakers ended up losing the battle for public credibility in the face of Nader and the rise of consumer advocacy in general. Although the structural integrity of the Corvair and its engineering design were eventually proven equal or superior to equivalent vehicles at the time on the road, and although judges also deemed that the evidence confirmed the ethically and legally required due diligence on the part of the automakers, the Corvair was pulled from the market after sales tanked, despite the lack of evidence for its alleged design flaws. The cause of most Covair accidents—as with most accidents in vehicles of all makes—was human incaution.

Whyte categorizes as a mistake Congress’ the establishment of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) since it introduces another expensive (and, for White, unnecessary) layer of government noodling that imposes financial burdens on automakers who, in turn, pass them along to consumers. Although The Sack of Detroit doesn’t mention it, the NHTSA’s regulations helped perpetuate the production life of the Ford Pinto by both establishing the financial limits to different categories of injury (from missing fingers to death) that plaintiffs could claim and absolving automakers from having to redesign any flaw if the cost of making the change would exceed that of paying court costs for death and dismemberment. Thus, Ford had no legal or financial reason to change the car until lawyers successfully focused on the ethical issues behind the status quo, legal or not. By presenting the suits for damages as class actions, a category of tort that allows plaintiffs to sue for punitive damages (available at the discretion of each trial judge) for actions deemed egregiously wrong, even if “only” ethically so. Lee Iococca—Ford’s president at the time—in his defense to not improve the Pinto’s design, repeated what his predecessors had said: Safety doesn’t sell.

Nadar’s attack against the Corvair resulted in both its discontinuation and diminutions of GM’s market share, profitability, and stock values lasting for decades. Public outrage and consumer protectionism was pandemic and not limited to GM, although GM took the brunt of the hit. All of the major players in this case at one time or another acted in bad faith, assumed the worst of its adversaries, and treat the public as idiots incapable of taking responsibility for their own poor decisions. Meanwhile, foreign automakers have been doing pretty well in the U.S., often beating GM at its own game.

Doctor Pascal

Doctor Pascal

Emile Zola / Julie Rose

Oxford World’s Classics

Doctor Pascal is Zola’s capstone novel in a 20-novel cycle examining changes at all levels of French society across several generations during the 19th century through two family lines—the Rougons and Macquarts. During this span and in this cycle, tensions play out between religion and science, Royalists and Republicans, and rich and poor—all traits both families embody or confront, and all of which Dr Pascal Rougon summarizes for us at the outset while explaining the family tree. (Each Rougon-Macquart novel stands by itself and does not require familiarity with any other book in the series.)

As the novel begins, Dr Pascal’s household consists solely of himself, his niece Clotilde, and his life-long, live-in servant, Martine. Living on the interest on accruing from his accountant’s investments of his income, Pascal has spent most of the past 12 years evaluating elements of genealogy that we would recognize today as genetics, but which did not exist in Zola’s time.

Delving into the mysteries of lives created was a realm fit only for clerics, not medics, and Pascal’s obsession with his family’s dual heritage is seen as heretical by the three women in his life, his niece, maid, and mother, Old Madame Rougon, aka Félicité. The religious differences between these women and Pascal sets the tone of chronic tension and ill-ease, especially between Pascal and his niece, whom Pascal has until this time seen as potential protégé for his idea.

The rift between Clotilde and Pascal comes to a head one dark and stormy night (with lightning for dramatic effect) when Pascal discovers that Clotilde has stolen the key from his desk and removed 20 years’ worth of research papers to burn. Pascal catches her before she can set them alight and, after a brief physical struggle that Clotilde loses, has Clotilde listen to her family history, going back five generations to the grandmother, from whose loins sprang three branches of the family, one legitimate, two illegitimate, describing their fortunes and failures. (The descriptions are plot outlines of the 19 novels Zola wrote over 20 years concerning the intertwined fates of the family branches.) Pascal hopes to discover, delineate, and publish the biological determinants of human physical and mental/moral development, using his own family history as evidence.

Yes, our family could, today, provide a broad enough sample for science, which hopes one day to mathematically define the laws governing irregularities of the nerves and blood that show up in a bloodline, following an initial organic lesion. These irregularities determine—in each individual in that bloodline according to their different environments, feelings, desires, and passions—all the natural and instinctive human manifestations, whose results go by the names of virtues and vices.

That is, Pascal believes in genetic determinism and a single source of “disruption” that corrupts the initial dispositions, which are seen as fixed and unchangeable. Publishing the family history, Félicité fears, will destroy the family’s legacy as noble and good. Obsessed with notions of family glory, Félicité devotes her energies to undermining Pascal every chance she can. And although shocked by his evidence and the apparent logic of his explanations, Clotilde is unwilling or unable to give up her irrational hopes that he will turn his back on his research and start attending church. This dispute plunges the entire household into an emotional abyss, since Pascal is again at war with all the women.

“I can’t live without certainty and happiness,” Clotilde complains to Pascal about the erasure of God from his genealogical studies, “What solid ground will I base my house on?” Pascal’s rebuttal—“we can’t satisfy every need at once”—is both lame and highlights the sense that, by the late 19th century, philosophy served solely to verify science’s claims (i.e., that science is the only legitimate method of knowledge production, and thus its conclusions could be assumed ahead of time to be true in all cases) rather than question them (per Australian philosopher Stephen Gaukroger’s observations). To our contemporary eyes, Clotilde’s strongest argument against science owes to the cruel conclusions about humanity (and thus God’s creation) implied and imposed by social Darwinism (itself not a science) and its merciless, amoral attitude toward the powerless in the name of evolutionary progress.

After months of acrimony and agony over the issue—in a not-unpredictable twist—Doctor Pascal and Clotilde confess their love for each other. Social scandal eventually ensues—not because they are uncle and niece, not because of the 35-year gap between their ages, but because they are unmarried. (So much for Pascal discovering the influence of family genealogy on fetal development!) However, the depth and profundity of their love initially ease the displeasure of even the most conservative of the locals, save for Pascal’s mother, Félicité, but only because she had other plans for Clotilde.

Félicité, Pascal’s religiously devout mother, refuses at this point to have anything more to do with Pascal. One day, she goes out to visit her Uncle Macquart, at 84 a life-long drunkard, only three years Félicité’s senior. Upon arriving at Macquart’s little house in the middle of nowhere, she finds him passed-out drunk, blotto on 90% pure alcohol—so drunk, in fact, that when his still-lit pipe falls onto his lap, it sets his clothes then Macquart himself on fire. Too drunk to awaken, his flesh continues to burn while Félicité quickly picks up her things and leaves without trying to stop the fire. She disapproves of his lifestyle, after all. When, the next day during his rounds, Pascal discovers Macquart’s charred remains, he also discovers one of Félicité’s gloves that she inadvertently left behind in her rush to leave the scene. Clearly, she witnessed Macquart’s death and did nothing to help. So much for Félicité’s Christian morality. (And Dr Pascal isn’t as free from Christian dogma as he would like to believe given his a priori assumption that infidelity (not incest!) naturally results on birth defects and a general moral turpitude among the children produced, accounting for the line of hereditary trash in his family. Zola inadvertently provides examples of what often results from confident assertions of scientific infallibility: Almost nothing of Pascal’s research, findings, and conclusions would be recognized today as scientifically valid today.)

Pascal and Clotilde are in their happy paradise, despite Mother’s scorn, and usually keep close to home, specifically, the bedroom. But trouble enters paradise after Pascal’s investor exits with all monies he had been entrusted with. Pascal’s household is soon reduced to a few months’ worth of savings.

Once the money finally runs out, Pascal, Clotilde, and Martine find themselves having to buy on credit. In the 19th century, buying on credit was a personal embarrassment, revealing a person’s underlying character as potentially bordering the sinful and indolent, of rash and imprudent choices that only diminish respect shown this now-indigent couple. The significance of this for Clotilde is that, unwed, with no money of her own, if Pascal dies, she will be left with nothing financially and will receive no help from the community because of her wanton lifestyle—one that wants all of marriage’s joys but none of its responsibilities. As it is, and with the encouragement of Félicité, the townspeople are scandalized by what they see as two unwed people without a penny to their names spending their days in endless shagging rather than earning incomes—and expecting to buy on credit from their neighbors on top of it all.

How these issues are resolved would take us into spoiler-alert territory, so enough. Suffice it to say that Julie Rose has cast Zola’s novel in a sprightly, assertive, contemporary English that never sounds anachronistic. Zola’s sexual candor was probably pretty bracing for bourgeios 19th-century Parisians, and although no longer shocking, that bracing effect comes through in all aspects of Rose’s translation of Zola’s Doctor Pascal.

______________________________________

My Big Brass Bed: An Intellectual Autobiography in Twenty-four Hours

My Big Brass Bed: An Intellectual Autobiography in Twenty-four Hours

Gary Amdahl

corona/samizdat

Barceloneta, November 28th, 3:00 AM, fine rain, high as a kite

I drove, aimlessly but alertly, fighting traffic around the basement. I pressed the big red plastic button in the middle of the knurled steering-wheel with the heel of my palm, but the horn didn’t work. . .

So begins Gary Amdahl’s excellent intellectual autobiography, Across My Big Brass Bed, 24 chapter-paragraphs across 288 pages describing the author’s life. It took me a moment, however, to realize that the date and time listed are not the date and time the narrative description begins. Gary Amdahl is not a stoned adult driving around his basement, crammed into a plastic car for toddlers. He’s a more-or-less regular guy, a 60-something simply recalling his childhood, born toward the end of the Baby Boom to a prosperous couple.

“Sensation and Catastrophe”—a phrase Amdhal uses several times throughout Brass Bed—could serve as the book’s alternative title. As an autobiography, it comes up short, chronologically, since most of its key events occur by the time Amdhal is 19, i.e., the mid-1970s. Brass Bed reads to me less as autobiography and more as Amdahl’s confrontation with the life-changing and awakening spirit and influence of his first lover, the improbably named Karla Popper, who seamlessly joined eros and knowledge in one body, spurring Amdahl’s own incipient interests in a life of the mind . . . before she disappeared from his life and before he could understand the sensations and ideas she aroused and integrate them into a harmonious rather than discordant whole, which is what he has become. Plenty of sensations, plenty of catastrophes.

Karla Popper was his social studies teacher, she 28 to his 14. Presumably dead from an illness she didn’t want Amdahl to know about until afterward. But before dying, she introduces him to varieties of sexual pleasure alongside the works of Karl Popper (of course), Martin Buber, and other intellectuals popular in the late ‘60s. (And her intent not so different from 60-year-old Doctor Pascal’s toward his 25-year-old niece, Clotilde, nor Clotilde’s reaction to that intent not so different from Amdahl’s to Karla. See the review of Doctor Pascal, above.) He’s a smart kid without direction: an “A” student, a first-chair flutist with private lessons and a strong interest (and ability) in playing baroque music, a kid with a drive to live a life of the mind—and engage in competitive motorcycle racing while stoned.

Amdhal’s initial reaction to Karla’s death is to spend his summer mowing lawns and tripping on hallucinogens. His parents’ divorce doesn’t help. He begins seducing girls his own age and making deeper forays into drugs and danger. Although he is eventually sent to a different high school, a new crowd, it doesn’t take young Amdahl long to ingratiate himself among his new peers. And after high school—well, he just needs to get out of town. So he leaves the state (Minnesota) and heads out to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where he hooks up with a motley group of current and former cycle racers.

Among this group of men in their mid-20s, who seem impossibly grown up to compared to himself, Amdahl’s 19-year-old brain slowly begins to develop a broader understanding of his frenetic self, a sense that eventually comes to a point of simultaneous im- and ex-plosion of emotional fragility brought on by an admixture of drugs, alcohol, and mourning for the dead Karla Popper. The undigested forces of literature, music, and motorcycle racing mingle with the loss of this key figure from his life. As Rilke might have leaned in to say, “You must change your life.” What changing his life requires takes Amdahl more than five years of ruthless self-examination to figure out. Across My Big Brass Bed is the amply rewarding fruit of that discovery. Strongly recommended.

Interview with Gary Amdahl:

You’ve written a dozen plays, most of which have also been produced. How did your conception of Brass Bed differ from that of your plays in terms of the effects on the audience you hoped to achieve? Brass Bed is a type of dramatic dialogue but one that probably can’t be staged. Dividing the book into hour-long chapters, each a single paragraph 30 to 40 pages long is a different pace for an audience than snappy dialogue in a drama.

My life as a playwright ended in 1989. I was sandwiched between Samuel Beckett and Sam Shepard in a one-act festival, and it went like this: wild applause, silence, wild applause. And I thought, it’s not the audience’s fault. There’s something I’m just not getting. To be fair (to me, to me, to me! everybody’s being so unfair!), big changes were underway in theater (basically, social cause propaganda in the mode of Disney and the transfer of foundation money from artists to administrators) and I was very happy to leave it all behind. (Although I did draft a play about Christopher Marlowe, and it made it to the finals at the O’Neill Center’s New Play Conference, something that, had it happened in ’89, might have kept me in the game.) But you’ve got hold of something important when you characterize Bad Brass Bowels as dramatic writing. I wanted the voice to be in a kind of spotlight and holding the audience in a kind of trance. I think this is at least partly due to my really strong response to Joseph Conrad’s (other) Marlow: the voice in the night and a dreaming audience.

Corona/samizdat is Brass Bed’s second publisher. I don’t understand how is it that this book isn’t a best-seller. It’s smart and funny, and anybody born in the U.S. during the ’50s can appreciate how well your prose re-creates the atmosphere of growing up during that time. What drove to you conjure up again those years of experiences and emotions?

I honestly do not know. First part: The ways of publishers constitute the revenues of the wicked, and are necessarily obscure. My first book was bought by Chip Blake of Orion Magazine, who’d just left the mag to do something different: run Milkweed Editions. But he left before it was published, and Daniel Slager took over. I’ll spare you the whiny details and just say that we didn’t get along. He reneged on a two-book contract (I Am Death was published but not Big Ass Bed), demanded his advance back, fired my editor, etc. My agent retired to have a child, but she recommended me to her boss, Bonnie Nadel (DFW’s agent), who said, yeah, it’s something all right but I’m not going to rep you. So I didn’t have an agent (for the second time: the first moved to Israel and became that country’s first female boxing champ). I knew Jack Shoemaker, of North Point Press fame, through Gina Berriault, whom he’d published along with Guy Davenport, Gary Snyder, Evan Connell, and sent him Back Bog Beast. He said, and I totally fucking quote: “It’s some of the best American prose I’ve ever read.” But he said no. Why? Don’t know. When another man (Rolf Blythe) became publisher of Shoemaker’s Counterpoint Press and published The Daredevils, Jack actively sandbagged me (no publicist for the first two months, just for starters) and said things like, “I don’t know why we published this, and I don’t want to read any more of your work.” Turns out they were trying to get Blythe out of there.

Second part: What drove me to write it is also a mystery! It took nine months and was never revised. I was very unhappy with The Daredevils, which I’d been working on, off and on, since 1984! Sex and violence, music and motorcycles: It was just a kind of Rabelaisian dream of creation that turned into a novel. I just really wanted to see the rest of the iceberg.

Just curious about what anybody from your hometown might have had to say about Brass Bed?

There are only two people in Minneapolis who I know have read it, and they are my oldest friends. They said what good old friends would say. They are in ideal positions to contest the accuracy of my memory—or rather, what has some autobiographical validity and what is ridiculous nonsense—but I think they knew I was trying for something superficially like an autobiography but essentially quite different.

How do you determine whether an idea is best suited to drama or prose? What are the strengths of each medium that particularly appeal to you?

Like I said above, my nights as a playwright are over. I would very much like to make a play again, but I’d have to, you know, direct it, and have enough money to hire good lighting, set, and costume designers (they are every bit as important as a playwright), and it would have to be in New York to matter in the least, etc. I am absolutely devoted to the idea of live theater, but I think I do better work writing about actors and acting in novels.

If I had to imagine what your home library looks like based on the style of Brass Bed, I suspect I would find Pynchon, Burroughs, Joyce and perhaps some other Modernists. Which authors’ styles, which authorial voices (more than content) appealed to you when you started noticing how things were being stated, in addition to what was being stated? What did you find so appealing, and did you yourself ever try to assimilate those different approaches to your writing? How do you think the writers and thinkers you most admire have affected your own writing, drama and prose?

Loveliest of questions! I have never felt the anxiety of influence, whatever Harold Bloom might have to say about it, and firmly believe I am made up of the authors who have gone before me. I would be nothing without them. There was a big explosion for me in the late ‘70s, when I graduated from high school and was determined to skip college, and race motorcycles while reading big novels in the back of the van: Melville, Joyce, Faulkner, and Pynchon were like the four corners of the planet. I made explicit attempts in notebooks to write like each of them (alongside notes concerning when and where I was to meet my dealer, Timmy G: speed and speed, now there’s a dream of anti-creation if ever I saw one). Tom McGuane (especially in Panama) and Barry Hannah (especially in Ray), who I was lucky enough to meet and hang out with, were also very strong influences. But there were three novelists who so completely spellbound me that I couldn’t even dream of writing like them: Halldór Laxness, Malcom Lowry, and Patrick White. Independent People, Under the Volcano, and Riders in the Chariot are for me unclimbable peaks. When I was writing plays, Sam Shepard, David Mamet (grrrr what a clown), and David Rabe were my masters, but it was Beckett and Strindberg that I wanted to reconcile in my work.

Are you able to reveal anything you’re currently working on without cursing the projects?

At this late date, I think a curse would actually help matters along. History Is Made at Night is the big one, about theater in New York in the ’50s and in Minneapolis in the ’80s, about devotion so strong to art and art only that life itself is put in jeopardy. It also deals with social protests and owes debts to everybody from Artaud to Erving Goffman’s The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life—not to mention the late great Julie Bovasso, who most people know only as John Travolta’s mother in Saturday Night Fever, but who also premiered, when she was twenty-five in the renovated parlor of an East Village ruin, Genet’s The Maids. (Genet came and was arrested in the “lobby” and deported.) Far from Heaven, Safe from Hell is the Marlowe novel, told from the point of view of a vagabond named Faustus, a hallucination of Marlowe’s who is, you know, his best friend. The Creative Writers is another hallucination or nightmare that equates creative writing programs and totalitarian superpowers. Finally, The Unanswered Question (nod to Charles Ives) is a fantasy about what my farm-boy granduncle might have been like if he hadn’t been murdered by third-rate gangsters. (My uncle, also a farmer, was murdered, too, by a vet of the Grenada invasion, which I write about in “Narrow Road to the Deep North.”) I’m not quite Anthony Burgess, but I do keep writing.

____________________________________

Bolt from the Blue

Bolt from the Blue

Jeremy Cooper

Fitzcarraldo Editions

An epistolatory novel of postcards and email exchanged between an artist named Lynn Gallagher and her mother, Bolt from the Blue begins in late 1985 with Lynn’s emancipation from a small, blue-collar town (where her mother works at one of the local pubs) to art school in London, and ends in 2018, with the death of Lynn’s mother.

In the beginning decades of their correspondence, neither woman neglects to give the other an acid bath of words with almost every exchange. The relationship is fraught with resentment and reluctant love and respect for the other. The mother is poor enough to rely on Christmas season tips to even out the spottier times of year, while Lynn goes from one success to another, doing well enough to have a house in London and a secret two-story studio that sounds like a re-purposed warehouse.

As Lynn’s mother complains to her, Lynn comes across in her correspondence as self-absorbed with her work and her recognition of merit by critics, fellow artists, and collectors. Perhaps that’s Lynn’s way of compensating for the ways in which she feels emotionally diminished by her mother. Mother and daughter don’t meet again until seventeen years after Lynn’s departure, on Lynn’s insistence. Her mother is hurt by the snub—and thus the cycle of resentment continues. As the decades go by, however, the recriminations dwindle between the two and they become more like friendly confidantes.

Cooper’s evocation of the mother / daughter relationship sounds convincing to me, a son raised by two parents. In comparison to Cooper’s Ash before Oak—which won the first Fitzcarraldo Editions Novel Prize and is similarly formed as Bolt, but rather than letters uses diary entries—Bolt lacks Ash’s raw, emotional, and visceral descriptions of a person emerging from a profound depression, which sound more like roman à clef than do the imagined disputes of a mother and daughter, realistically described as their relationship is.

Cooper should also be lauded for the verisimilitude of the exchanges by the addition of ragged edges of this narration: Those gaps between correspondence in which questions go unanswered, events and persons go unexplained, and so forth—just as one might expect from a fragmentary epistolary record—but whose lacuna seem natural, unforced, and leave no questions of significance unanswered. And of course, what seems supremely ironic to the parent, is the (now older) child’s confession to the parent: Forget what I said earlier. We really are alike, you and me.

Reading Is Walking: The Encyclopedia Series

Reading Is Walking: The Encyclopedia Series

Gonçalo M. Tavares / Rhett McNeil

Quantum Books

Gonçalo Tavares, like Pierre Senges, is a writer of great renown in Europe but little-known in the U.S. In such novels as Jerusalem, Joseph Walser’s Machine, Learning to Pray in the Age of Technique, and A Man: Klaus Klump, Tavares mixes eccentric whimsy with surreal situations and characters who are more of types than complex and contradictory people, yet Tavares achieves a realism of ideas, of different ways of seeing the world and testing philosophical notions—an achievement that permeates his characters and situations with a lived reality, enabling empathy and sympathy from the reader.

The writings of Tavares and Senges thrive on playful imaginings based on taking premises to their (il)logical conclusions, much in the way of Italo Calvino and Georges Perec, with a faint whiff of OULIPO in the air, setting the mood, if not the techniques Tavares and Senges use. Tavares’s novels come from various of his numbered notebooks, each on different themes. The novels listed above come from his Kingdom series and the book under review, Reading Is Walking comes from his “Encyclopedia” notebooks, which deal with defining and illustrating the ideas and conditions described in the five “Brief Notes on” sections making up the series on science, fear, music, literary connections, and something he calls “Bloom-Literature.” As his entry on tools indicates, from his Brief Notes on Science, not all of his entries are whimsical:

By placing metaphorical language outside of science, a whole set of possible solutions are excluded and, therefore, a whole set of problems as well.

It’s like have a wooden beam that needs to be sawed, but the carpenter insists on using only the hammer. Since he will not be able to saw the wood with that tool, he says to himself: why saw the wood? I don’t really need to saw the wood. This isn’t my problem, he’ll conclude.

For the foolish carpenter, his problems are the ones that he is able to solve with the tools he knows how to use. He doesn’t start by looking around and detecting his problems. He starts by looking at the tools he knows how to use.

On fear and expectations: “You perfect your expectations in such a way that when you arrive at old age you no longer expect anything from the word, from mankind, or from animals.”

On listening to music:

The manner of delaying the world’s onward march forward can be called labyrinth.

The labyrinth, however, as the geometric—and psychological—inverse of the straight line.

The shorted distance between two points: the straight line.

The longest distance between two points: the labyrinth.

Therefore: the labyrinth as the anatomical enemy of the straight line.

And the human ear, let’s return to it, possesses a labyrinth instead of a straight line.

The labyrinth, delaying that which comes from the outside, gives the brain time to prepare for the arrival of sound. The labyrinth of the ear is a symbolic form of preparation and digestion.

And thus, then, two possible ways of listening to music: the listener who listens in a straight line and the listener who hears by respecting the shape, with its many curves, of the ear. This is the patient, unhurried listener. The other is deaf.

Reading Tavares is like watching cloud forms change, mutate, and evolve in unexpected directions but from the simplest of materials—in Tavares’s case, words and thoughts.

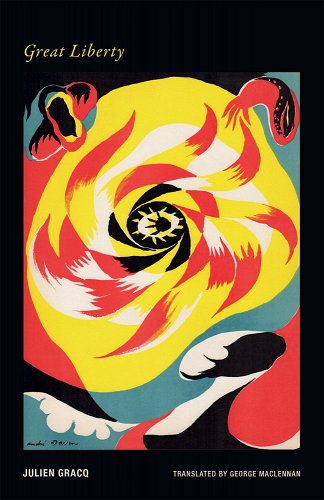

Great Liberty

Great Liberty

Julien Gracq / George MacLennan

Wakefield Press

Great Liberty collects all of Julien Gracq’s prose poems and translates them into English for the first time. Graq’s prose poems—short scenarios, most ranging in length from a paragraph to two pages—are sketches of places or persons that bear the impression of surrealism’s influence in his choice of metaphors and similes. This influence doesn’t transform Graq’s prose poems into surrealist exercises but instead extends his rhetorical techniques so that his poems’ initial dream-like qualities are shown to be, through cumulative effect, more accurately described as extravagant but emotionally acute descriptions of Graq’s chosen subjects. The Great Liberty of the collection’s title becomes, then, the liberty of visions free of conventional descriptors, often arrived at via verbal collages: Think of Burroughs’s cut-ups with the added labor of yoking them to coherence rather than, a la Burroughs, using the cut-ups to abolish conventional methods of coherence. (And Graq’s use of collage precedes the cut-ups of Burroughs and Gysin—Great Liberty was originally published in 1946.)

Graq’s prose poems read like exercises in technique—etudes, if you will—that seem lifted from (or depositable into) larger scenes, serving to set the tone. Let “Surprise Parties at the Houses of the Augustules,” quoted here in its entirety, represent the book’s methods and tone:

This morning the pavements are stairways where beautifully aligned cascades vaporize in a perspective of petrifying fountains. Not a breath of wind, but, on the boulevards, as far as the eye can see, the branches of the chestnut trees crack one by one with an audible sound of musket fire. From time to time some heraldic book bindings explode on the bouquiniste stalls along the Seine—giant seed pods burst open on the bars of cafes. Wooden faces everywhere; the day promises harsh weather; a dense hail of balls of laundry blue is reported at intervals on the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève. At the crack of dawn, crowds of postmen are at Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre, however, humble laundry workers coalesce at Saint-Nicholas-du-Chyardonnet—the cannon is methodically fired every twenty seconds behind the altar of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois. It’s unheard of, it scandalizes; at each detonation the archbishop makes pigeons fly out of his sleeve. Gazelles emerge in crowds from brothels and flock together on the municipal squares.

If the techniques behind Great Liberty have a musical corollary, it would be Chopin’s etudes, which transformed the development piano-playing techniques from dull, pedantic exercises into musical statements in their own right, as tune-like as any other form of fully developed art music. Beautiful, weird, oddly un-surrealist, and recommended.

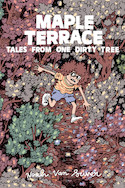

Maple Terrace #1

Maple Terrace #1

Noah Van Sciver

Uncivilized Books

Noah van Sciver returns to his financially impoverishment youth (described in One Dirty Tree) and finds more comedy gold sieved from a slurry of childhood / tween embarrassment, covetousness, deceit, revenge, and salvation: sibling rivalry, parental abuse, nerd-shaming, bully placating, and more! Few people have the market on self-mortification the way cartoonists do, and van Sciver is on a solid mid-career run in expressing it, with Maple Terrace coming on the heels of his award-winning Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormons. Looking forward to the second and third installments of Maple Terrace—the second apparently already with the publisher.