The Woman Who Killed the Fish

The Woman Who Killed the Fish

Clarice Lispector / Benjamin Moser

New Directions

Four children’s stories from the master Brazilian author, who brings a skewed, slightly surrealistic view of her subjects, both menacing and promising, originally written for her sons. Benjamin Moser, Lispector’s translator, captures the cadences and rhythms of real speech (English), specifically the patterns we fall into when addressing children. Thus, the stories also convey to readers the humor of hearing an adult talk to children about the real and ridiculous things she talks about.

In the eponymous first story, the narrator (usually identified as Clarice) talks to children about different creatures she’s owned and that have invaded her house (cockroaches, lizards). The story is metaphorically a trial case summary to a panel of judges (the listening children) regarding her confession to having allowed three pet fish to die. Clarice’s anecdotes demonstrate her general love for animals, which allows her to beg forgiveness for neglecting to feed her son’s fish for three days:

I’m going to tell you a few very important things so you won’t feel sad about my crime. If it were my fault, I’d own up to you, since I don’t lie to boys and girls. I only lie sometimes to a certain type of grownup because there’s no other way. Some grownups are so awful! Don’t you think? They don’t even understand a child’s soul. A child is never awful.

The three other tales are also about pets and domesticated animals, “The Mystery of the Thinking Rabbit” (the ability to think is a constant throughout these stories, “Almost True,” and “Laura’s Intimate Life” (by “intimate,” Clarice quickly clarifies, “we shouldn’t tell everyone what goes on in our house”). Because these are tales by Lispector, the “thinking” her creatures engage in is a bit odd (including the jealousy of a fig tree for eggs).

Much fun and—as with all else by Lispector—strongly recommended.

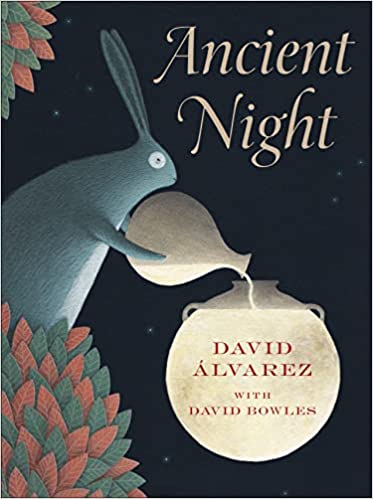

Ancient Night

Ancient Night

David Alvarez with David Bowles

Levine Querido

David Alvarez illustrates a story written by David Bowles that takes two figures from indigenous Mesoamerican lore—a rabbit and an opossum—and recombine their stories to create a new myth. This new story tells of how night and day came to be. Muted colors, backlighting, and black, starry skies set the story-at-bedtime mood and illuminate the mostly mute and benign rabbit and opossum going about their fated rounds to help shape the world we know. Two pages at the book’s end explain the mythological backgrounds of the tales and the symbols at play. Recommended for ages 4-8.

The Joy of Quitting

The Joy of Quitting

Keiler Roberts

Drawn & Quarterly

Keiler Roberts’ cartoons on young motherhood serve as a counterpart to another cartoonist from Drawn & Quarterly, Guy Delisle’s Neglectful Parenting series: domestic comedy regarding chores, raising a child (two for Delisle), and dealing with a spouse and (for Roberts) one’s own parents. I suppose the cartoonist spirit hovering over both Robert and Delisle is Bil Keene’s “Family Circus,” but the death of newspaper comics and the need to appeal daily to the mawkish, cutesy sentimentality demanded by a mass audience, has given cartoonists room to deal more honestly with domestic perils and frustrations—and, with Roberts, medications for parental emotional health, visits to the gynecologist, and other intimate matters. Roberts is also able to include innocent scenes of nudity (her own or her child’s), mostly in bathrooms. The humor is typically droll, as in this example, whose dialogue I quote:

Amie came to visit Chicago and stayed at our house for the first night we were away. I got to see her just long enough to take a walk.

[Keiler:] You have to take the balloons home with you. They’ll be deflated by the time we get back.

[Amie:] I will definitely not do that.

[Keiler:] Why not? Your kids would be so happy.

[Amie:] I hate balloons. I hate them bouncing around and they last forever.

[Keiler:] Yeah, I hate them too.

Will you take some mangos?

[Amie:] Yes.

Think of The Joy of Quitting, then, as a mango.

___________________________________________________________

Publisher Profile: FC2

In 1974, six American writers banded together as a Fiction Collective to promote and publish accessible works of narrative prose that are also innovative. The collective now has a hundred members and awards to cash prizes every year for unconventional narration. It’s been a long time now, but I think the first of their books I read was Mark Leyner’s first collection of short stories, I Smell Esther Williams. (If you’re unfamiliar with Leyner, treat yourself to one of his collections or novels.) They’ve published over 200 books so far, with authors ranging from Kim Addonizio to Magdalena Zurawski. Revamped many years ago as FC2, their books are now published by the University of Alabama Press.

Benefit Street

Benefit Street

Adria Benardi

Benefit Street begins with a group of women friends meeting at a teahouse they’ve been frequenting since college, long before they became the various professionals they are now. Told from the points of view each woman through interweaving chapters, we slowly become aware of each woman’s background and current life, the struggles that await them yet.

Taking place in an unnamed Middle Eastern country, the government is officially secular but there are clues that, while boys and girls are educated together, that practice is recently new, and many citizens fear a return to conservative ways, which may be determined by any number of influential people in politics or religion. This is the women’s greatest overriding fear: that at any moment all the freedoms that make their lives meaningful may suddenly vanish, based on the whims of governmental or religious leaders. And that applies to their daughters too.

No longer naïve undergraduates, these women painfully endure contradictions within their families, religion, community, and nation that now affect them not just as women but also as wives, mothers, daughters, and employees.

Those from the women’s circle who come from the countryside—whose memories of the past and duties of the present to family members left behind—highlight the tensions Arab women can feel between the freedoms available to them in cities and the opportunities denied them in the country. But even having “progressive” parents—those whose household does not segregate eating areas between men and women—does not mean they favor college educations for their daughters. Or for their daughters to marry whomever they choose.

The differences between country and city are economic, too. One woman’s mother, who lives in the country, has no electricity for anything, whereas, in the city, most people of turn on every light in the house for no reason at all.

Convincingly depicting women with complex lives and conflicting emotions embedded in a nation run by men hostile to their autonomy, Adria Benardi’s Benefit Street is a generous and moving depiction of sharply circumscribed lives.

Shame

Shame

Grant Maierhofer

A series of autofictional musings on the challenges of living with OCD and alcohol / drug dependencies while managing a job and the responsibilities of a husband and father of two (one with cerebral palsy) with zero self-esteem.

I like it when human beings take whatever violence the majority of humanity projects out into the world and direct it inward. Not suicide, not really, but this long slow process of fighting with oneself, remaining at odds with oneself, at war with oneself. That’s what’s important to me. . .

Maierhofer’s self-hatred includes—but is in no way limited to—swallowing a live coal to produce an injury that will prevent him from speaking and require time for healing that will absolve him of his other responsibilities so that he can ultimately—the goal of the coal-swallowing—spend a month alone writing. Other bad ideas permeate every page of this often squirm-inducing book, shocking both for what the author does to himself and his ability to live through it.

As the stories go on, however, and certainly by the book’s last section, they become more nuanced—no “After all, tomorrow is another day” nonsense—but a view of life more accepting, tolerant, and self-aware of the unreasonableness of his drives coupled with better skills at detaching himself from his self-loathing.

My Haunted Home

My Haunted Home

Victoria Hood

Although presented as a short story collection, My Haunted Home can also be read as a novel consisting of snippets of an unhappy, morbid, and claustrophobic life, beginning with the first story, “The Teeth, the Way I Smile,” which sets the tone for the rest. In “The Teeth,” the narrator sees her dead mother in various parts of her own body whenever she looks into the mirror. But by turning on the bathroom light, she imagines that the mirror yanks her mother from her grave, bringing her unhappiness with her. From there we go to “I Like It,” whose narrator enjoys (at least fantasizing about) cannibalizing herself (extracting the unhappy spirit of the dead mother?). There are ghosts here, too, reminders of her unhappy history.

But the stories may also be read as exercises in morbid fantasy—a woman’s arms grow to snake-like lengths, another’s legs refuse to act as her mind commands, another cuts herself to either drain her body of blood and bad spirits or to allow spirits to enter her body. Sex tends to occur in locations that are public and flagrant or private and humiliating.

Part II of Home consists solely of the short story “You, Your Fault,” which at 15 pages is also the longest in the book. The narrative voice switches from the first- person singular “I” of Part I (a relief after so much of the emotionally draining effects of its solipsistic “I”) to the second-person singular “you,” a move which presumably acts to put the reader in the narrator’s position to achieve an emotional immediacy unavailable via, say, omniscient third-person narration. The move to greater immediacy, including use of the present tense, however, is undercut by a lack of narrative describing an emotional reaction to anything described. Emotions are named but not discussed, and actions are listed as matter-of-fact instances of affectless behaviors. Hard to get close to such narrators or feel a compulsion to see what happens next. Is this numbness the literature of autism?

The Assassination of Olof Palme: An Anthological Novel, Vol. 1

The Assassination of Olof Palme: An Anthological Novel, Vol. 1

Rick Harsch

corona\samizdat

Rick Harsch, author of The Assassination of Olof Palme and publisher of corona\samizdat, recently posted a video who topic was on a trend in publishing that I have noticed lately: There seems to be a trend now among some U.S. writers for maximalism—writers who produce densely detailed and knowledgeable books on a wide range of subjects among the arts and sciences, books often 500-1,000 pages long, some eager to discuss ideas, others mainly to enjoy the art of oral storytelling, but twisted in ways similar to R. Crumb’s retooling of cartoon icons from the silent era. Rather than the minimalism of, say, Raymond Carver, where 99% of a story’s semantic content is somewhere between, above, and below the words, a maximalist enjoys the shear act of reeling off one anecdote after another, following and reporting diligently on any variety of rabbit holes. For reasons I can’t fathom, the writers most interested in maximalism seem be white men, ages 45-70, published by small, indie presses, sometimes located in, as in the case of corona/samizdat, foreign countries. Volumes 1 and 2 of Assassination total a little over 700 pages and include contributions from 50 other writers woven into the narrative. It’s creative, innovative, and often funny.

The following definition of “Manippean satire,” largely cribbed from the efforts of Wikipedia’s various editors and writers, concisely defines the labyrinthine digressions comprising Assassination’s volumes: “a form of satire, usually in prose, that is characterized by attacking mental attitudes rather than specific individuals or entities” (well, the specificity stuff is in full force here,) “a mixture of allegory, picaresque narrative, and satirical commentary.” Henry Fielding, then, via William Burroughs, minus the heroin and sodomy—which, in the case of The Assassination of Olof Palme, would pretty much be icing on the cake.

Although discontinuously veering from one set piece to another, a sense of an overarching theme (i.e., moral outrage) gives the narrative cohesion, despite or because of the fragments. The anecdotes and digressions include long musings on suicide in Slovenia since the fall of the Soviet Empire; how the person who seems to be the primary narrator ended up crashing in a dead man’s apartment under an assumed name—the dean man’s; justified rants against Nazis, Nixon, and North (Oliver); etc., ultimately culminating in a wedding at which a table of multinationals, between conversations on the evil shenanigans of Eastern European leaders during WWI, engage in a farting competition. Yes, a lot of unpleasant behavior and history is covered here but that’s the point of black humor.

The most important attribute of Harsch’s narration is the voice—a voice which has a long tradition in American letters and popular culture—the voice of the hucksters in Huckleberry Finn, the patter of snake oil salesman, Mr. Marvell and the Wizard of Oz, Mr. Haney from “Green Acres,” TV evangelists, and of course Mark Twain—the huckster-cum-raconteur who distracts with slight-of-word during poker games, cheating himself to the win but not before first entertaining everyone who eagerly participated in the con, which may turn out to be a shaggy dog story, but endings are hardly the point in disjointed narratives.

I’ve begun Volume 2, which so far hints at an explanation for how the American narrator came to be in Slovenia‚—but the explanation, alas, raises even more questions. Stay tuned!

The Art of Noises

The Art of Noises

Luigi Russolo / Doug Skinner

Black Scat Books

The early 20th-century arts movement known as Futurism—fascism’s aesthetic offspring exhorting for, per its founder Filippo Marinetti, “violence, cruelty, and injustice”—was practiced mainly by writers and painters. Only a few musicians and composers took up Futurism’s mantle, sparked by Luigi Russolo’s “The Art of Noises: Futurist Manifesto.” Russolo himself was not a musician but instead a painter and inspired tinkerer who invented and composed for noise-making devices. The Art of Noises includes the title essay and other essays on noise as music and the instruments he invented—the intonarumori—to achieve the effects he was after.

What Russolo meant by “noise” included not just the cacophony of machinery: “we need only think of the rumble of thunder, the whistling of the wind, the roar of a waterfall, the babbling of a brook, the rustling of leaves, the trot of a retreating horse, the trembling jolts of a cart over cobblestones,” and so forth. The difference between noise and music is illustrated as the difference in sounds produced by a piece of sheet metal that is violently struck versus being bowed: “the vibration that the sheet received, given the violence of its excitation, was irregular” but the bowing “produc[ed] a regular and period vibration.” From this difference, Russolo deduces that “A noise is generally much richer in overtones than a sound” (Italics in the original throughout the review).

Furthermore, Russolo was not content to take unpitched sounds as they are but to “tame” them, set their pitches in a way that would allow for their orchestration. But in standardizing these pitches, Russolo was not interested in developing a bank of machines that merely imitate already-existing sounds. From there, Russolo goes on to tabulate “6 families of noises” and concludes his manifesto with eight proposals and their rationales for creating Futurist music.

After the manifesto are essays describing audience reactions to performances of his intonarumori, real-life examples of noise symphonies, and developing a notation system for his instruments. Russolo sums up the behavior of some members of the audience at the premiere performance of his noise-making machines who, to his exasperation, paid for tickets and made the trip to the theater solely “in order to refuse to listen to anything!!” The disrupters turned out to be musicians and music professors who, in turn, were accosted by Futurists in the audience, including Marinetti, who saw an opportunity for a brawl. Eleven of the disrupters were allegedly sent to the hospital, whereas the Futurists sent themselves to celebrate at a bar.

Given the celebration among Futurists of all that is violent, it is no surprise that Russolo comes to effuse about “The noises of war.” Russolo outlines the sounds, pitches, and timbres of the bullets, rifles, machine guns, grenades exploding, and rockets soaring, landing, and exploding that he heard while serving in the military during WWI. For the violent-minded Futurists, war produces the sounds of tomorrow’s symphonies. The noises symphonies produce should also include, per Russolo, “The noises of language”; i.e., the production by mouth of onomatopoeia, where “the consonant . . . represent[ing] noise . . . multipl[ies] the elements of expression and emotion,” examples and explanations of which come from Marinetti.

Chapters 7 and 8 focus on standardizing the notation of the noises and argue why standard systems of tuning should be abandoned. (His solutions either tend to be inelegant or already in existence but unacknowledged by Russolo.) And Chapter 9 describes the various types of intonarumori he has already invented, how they are operated, and the types of noises they produce, including Howlers, Roarers, and Cracklers, Rumblers, Rubbers, and Bursters, Bubblers, Buzzers, and Whistlers, and Gurglers.

Neither Igor Stravinsky or Edgar Varèse were impressed by Russolo’s instruments, perhaps in part because, as audience members complained, they were too quiet (!!) to hear, apart from some humming and buzzing.

A Perfectly Ruined Solitude

A Perfectly Ruined Solitude

Kristofor Minta

Sublunary Editions

A book of poems written for the poet’s brother. But: “There is no brother. He is only in my head. Whoever reads this is my brother. You’re looking at someone fostered, adopted, a one-time ward. A family took me in and gave me a sister, so I know what that’s like. But I always wondered if, out in the world, there were a brother, a confidant, someone stitched with the same thread.”

That’s the book’s premise, one based on looking, relating, warning, teaching, and loving—in the hopes that one is not merely talking to oneself. “This is the ballroom scene. / I’m teaching you how to dance. / Look at them all, just like us, / carbon with notions.” The narrator’s wants are simple: “But I’m keep for myself. / That one is mine to write. / See this hollow tooth? / I can fit enough cyanide in there / to kill ten of me. . . / but it won’t come to that. / If I need to open a vein, / I even have friends / who would help me do it. / Yes, I agree, pretty good friends.”

The poems are Minta’s ways of talking to himself, finding the companionship within himself for himself, a companionship that will allow him to ruin his solitude, perfectly.

I was out walking the fence row

after dinner.

Your spirit bled across the fields,

over the fence posts and the trash in the weeds,

and left slanting shadows.

Your blood was warm but I could feel

the earth begin to cool toward darkness.

A goose, then geese high up

moving from empty nests to

the nests they will fill.

It came to me that even you have limits,

that distance was the first spark in your heart.

Lives of the Saints

Lives of the Saints

Alan Franklin

Black & Red Books

A collection of short short stories, anecdotes, cautionary tales about grinding lives under capitalism and attempts to avoid its pestle. The narrator is a curmudgeon who relates the lore of dead-end jobs left gleefully and dead-end hook-ups ended embarrassingly—like Bukowski, but minus the whoring, fistfights, and days and nights spent in bars.

From “Yes, But What Are You Feeling?”

Get out and see the world, my father said the first time he pushed me out the door. The wind howled remorselessly about my ears. But father, I’m only three, I shouted at the top of my little lungs. Stop making excuses, he shouted back through the closed ad locked door, you’ll never get on in the world if you keep avoiding challenges. . . I think the idea of fatherhood appealed to him in the abstract—he was a great on for brief, volcanic enthusiasms—but the reality of a snotty, pukey, crap-laden, drooling dependent soon cured him of any lingering illusions he harbored on that score.

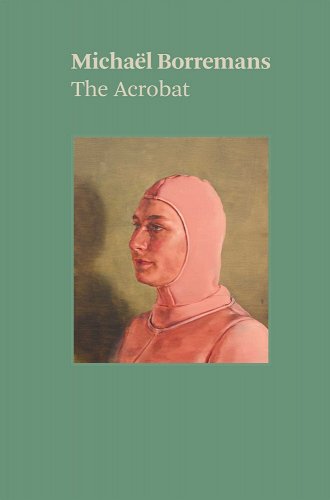

Michaël Borremans: The Acrobat

Michaël Borremans: The Acrobat

Katya Tylevich

David Zwirner Books

“I do not paint fact and I do not paint portraits”— Michaël Borremans

Michaël Borremans: The Acrobat is a brief monograph on two series of paintings committed during the pandemic, one from 2021 collectively and parenthetically titled Design for a Sculpture, the other from 2022 collectively titled The Acrobat, both series of paintings reproduced to accompany the essays.

Design for a Sculpture shows various larger-than-human vitrines, most with people in them, such as “Five Writers” and “The Fog.” The figures in the vitrines are unidentified, and the distance between the works and the viewing audience establishes an emotional distance, too, that encourages viewers to question their relationship to art and to other people.

The Acrobat consists of eight (non) portraits with such titles as “The Racer,” “The Witch,” “The Acrobat,” “The Pilot,” “The Apprentice,” and so forth, each figure wearing a costume or make-up suggesting something performative, with expressions looking pensive, unself-conscious, and unaware of an audience. A narrative is implied by the grouping of portraits and their similar proportions. What that narrative might be is left to the viewer.

While Katya Tylevich’s essays lean toward academic assessment, they do provide insights and facts about Borremans’s creations that help open them to understanding or better appreciating the mysteries they embody.

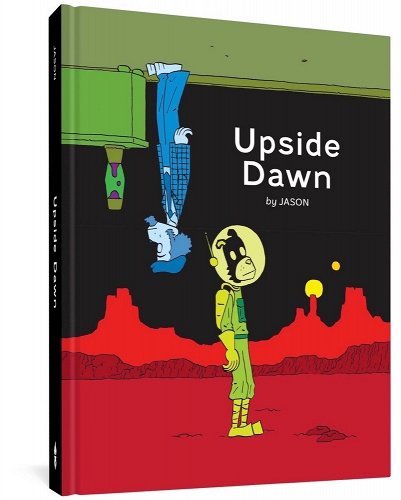

Upside Dawn

Upside Dawn

Jason

Fantagraphics

Upside Dawn is cartoonist Jason’s strongest collection in some years, one strongly influenced by the literary: There’s an ode to George Perc in the form of a conventional murder mystery told with constraints, another for Joe Brainard’s I Remember, and Kafka retires from the Castle and is abducted into a new life per Patrick McGoohan in The Prisoner, with strikingly similar results. There’s even a straight-up version of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. Creatively, this work feels like a break-through moment for Jason, inspired by a diverse range of sources and a willingness to experiment more with verbal/visual contexts. Long-time fans will love this, and newbies will want to check it out because it’s excellent and represents the current state of Jason’s art.

Very interesting review of Olof.