“To romanticize the world is to make us aware of the magic, mystery and wonder of the world; it is to educate the senses to see the ordinary as extraordinary, the familiar as strange, the mundane as sacred, the finite as infinite.”

~Novalis

From Elizabeth Zuba’s intro to Clive Philpot’s interview in Bomb Magazine:

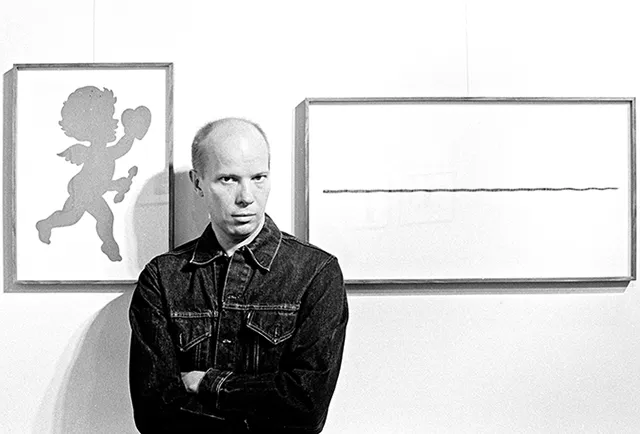

“Almost twenty years after his death, Ray Johnson continues to be revealed as one of the most consequential figures in American contemporary art. The progenitor of correspondence art and an influential pioneer of pop art and conceptual art (though he eschewed all of these monikers), Johnson’s curiosity resulted in an immense body of work that spans collage, correspondence, performance, sculpture, drawing, painting, and book arts. For better or worse, he embodied that over-glorified and under-recognized role of “the artist’s artist.”

Born in Detroit, on October 16, 1927, Ray Johnson attended Detroit’s Cass Tech high school and Black Mountain College in North Carolina (1945-1948). He died from a suicide drowning on January 13, 1995, in Sag Harbor, Long Island. Well known as the father of mail art, he was a collagist and a creator of ‘nothings’ which is what he called his performance art. He was a networker, a designer of book-jackets, and artist books. His art was a marriage of imagination and wit, mortality and mystery. He brought light to the levers and mechanics of communication, art appropriation, and pop-culture. And his untimely death was connected to everything.

“His interest in codes, poetics, and semiotic systems looked back to Duchamp, while anticipating the enlarging contemporary conceptual practices, and the development of appropriation in particular, during the early second half of the 20th century.” —Adriane Little

“A brilliant, uncontainable polymath, an artist-poet, the genuine item… Mystery is part of his beauty and lastingness.” ~Holland Cotter, The New York Times

*

How to Draw a Bunny (dir: John Walter, 2002) from BASEBALZAC on Vimeo.

How to Draw a Bunny (2001) was a film that mirrored Johnson’s artworks. It echoed his artworks and connections, a funhouse of collage, with artist interviews, disguised as a noirish murder mystery. The title was taken from the iconic Ray Johnson bunny, an alter ego and jokster, as inscrutable, flat, and deadpan as Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy cartoons. Ray’s bunny and Nancy share the same blank punk attitude, they are coded, layered, ambiguous drawings. How to Draw a Bunny is one of the best artist biographies on film.The estate of Ray Johnson described it online:

“As both investigated and represented by filmmakers John Walter and Andrew Moore, How to Draw a Bunny is itself a collage of photographs, art works, interviews and letters, home movies and video, that flow at the viewer like a jazz ensemble. With exceptionally toned care and constructions, the filmmakers penetrate a “rabbit hole of an art world wonderland” and reveals not only an artist’s fragmented life, but also the universe of his peers, friends, critics, and colleagues….the experience of an artist who wore many different faces and treated the art scene as a game without a prize.”

*

Mail art shared roots and similarites with 19th century scrapbooks, the growth of chromolithography, cabinet cards and carte de visite celebrity photography, calling cards, advertising art, and postcard collecting. Mail art became an ephemera craze in the 1970s and ’80s with mail-art shows turning up around the world, along with a profuse production of rubber stamps, all to the chagrin of Johnson, who saw the medium explode beyond his once intimate circle of friends and artists. Ray reluctantly settled into his fate as father figure to the movement.

Johnson’s collaged and painted images of James Dean and Elvis appeared a decade or more before Warhol began using pop icons, and his New York Correspondence School foreshadowed the internet with its open distribution network. Johnson’s appropriations were torn directly from fan magazines, and their small size stood in contrast against the gigantism of pop-art. Many of Johnson’s mail-art pieces were distributed as mass-produced flyers of his drawings folded into envelopes. An early beginning point can be traced to his 1943 letters sent to his high-school friend Arthur Secunda. The letters reveal a quicksilver mind, beautiful cursive lettering, and an obsession for celebrities, released in a torrent by the mid-1960s.

*

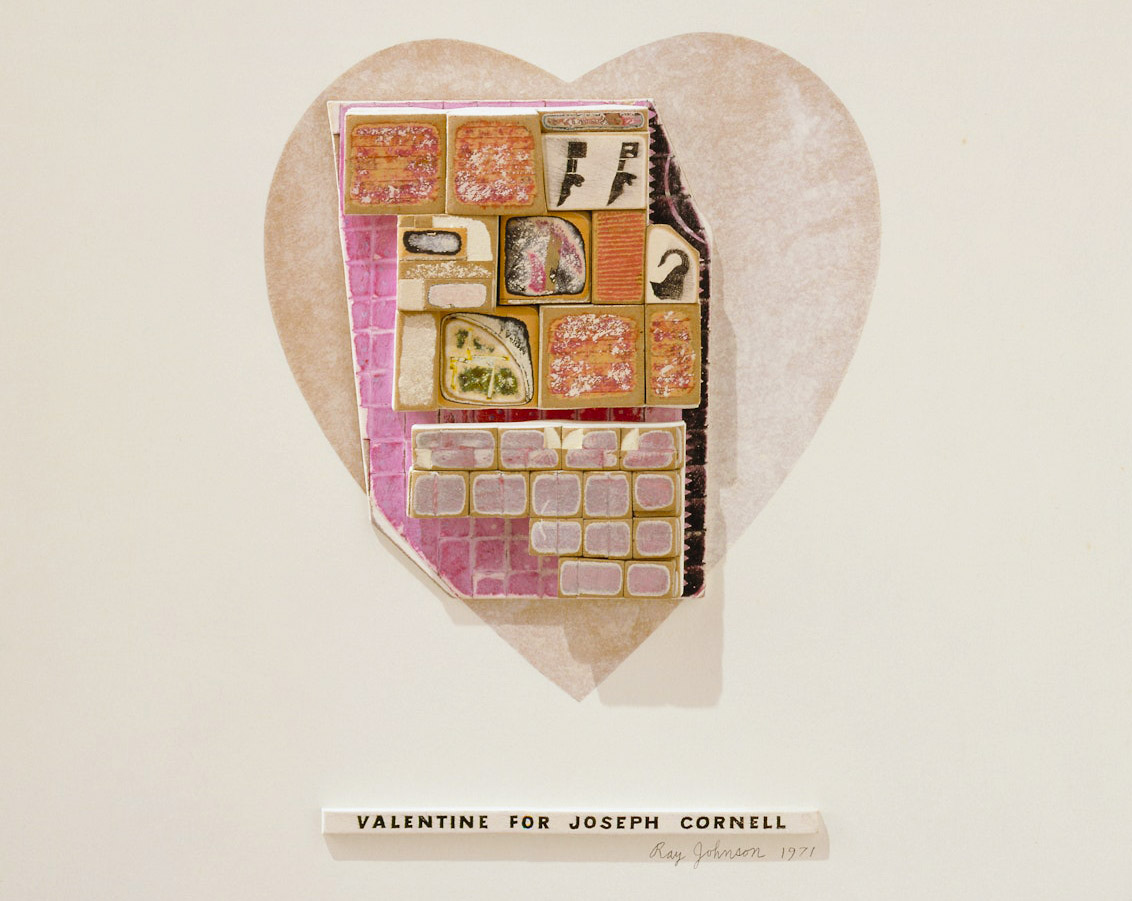

Joseph Cornell and Ray Johnson both collected ephemera, and worked with collage as their main medium. The personalities of the romantic ballet were an obsession for Cornell and he presented them in boxes and scrapbooks, writing about these figures as richly designed fairytales–mixing history with myth, filtered through his personal experience.

Joseph Cornell and Ray Johnson both collected ephemera, and worked with collage as their main medium. The personalities of the romantic ballet were an obsession for Cornell and he presented them in boxes and scrapbooks, writing about these figures as richly designed fairytales–mixing history with myth, filtered through his personal experience.

Johnson also collected images of famous actors, artists, and celebrities, but unlike Cornell who was building an altar to one sided love affairs, Johnson chose to gather a net of pop-culture names, and involved the recipients in an art-game that was a two way street, egalitarian and humorous. Johnson’s figures were subjected to satiric jabs and digs with complex layers of punchlines, flattened into cartoons and his tradmark routines of hand-lettered names and bunny heads. Both artists saw and created artworks as a gift exchange; a ritual of creating that was personal and romanticized.

*

At a legendary happening in 1969, Johnson rented a helicopter at the 7th Annual Avant Garde Festival in Long Island and dropped sixty foot-long hot dogs over the avant-garde celebrants. “We zoomed in over the East River Island and saw below avant-garde people waving at us. We finally hovered at a spot where I was to drop the dogs.,” wrote Johnson , “Like bombs away, I pushed the foot-long hot dogs through the round hole in the plastic helicopter bubble, and they fell.” Some of artists below were seen eating the hot-dogs. Quotation from a Vanity Fair Meet Ray Johnson exposè.

*

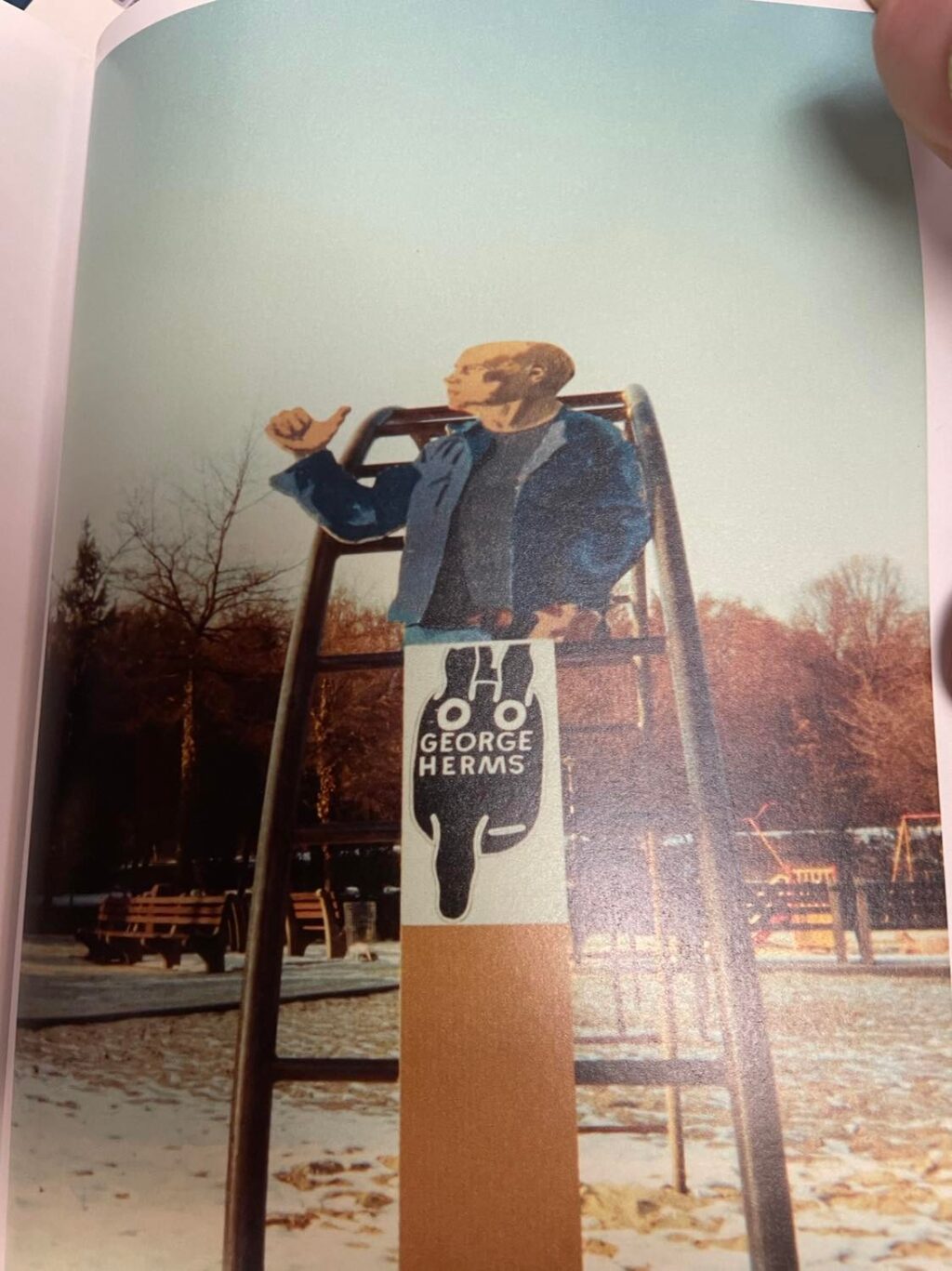

RJ Cutout Painting and George Herms Movie Star in Playground, 2inter 1992, plate 148 in; Please Send to Real LIfe: Ray Johnson Photographs

Artist Jim Pallas (b. Detroit, 1941) was introduced to mail-art through his friend Roy Castlebury, (1947-2007) a Detroit artist who passed along Ray Johnson’s address. Pallas was also invloved with the “Space Atlas Notebook” activities of Dana Atchley, a mail-artist, and book artist from the 1960s. “I brought Atchley to Macomb College to lecture,” said Pallas, “And he did his last presentation of his Art Space Show there. It was a big hit among the students.”

Inspired by Atchley’s archive of art documentation, and an upcoming Detroit mail-art show, Pallas began the “Hitchhiker series,” as an extention of his ongoing mail-art projects. The hitchhikers were stand up sculptures, made by tracing silhouettes and painting figures of artists, relatives and friends onto wood, and attaching a wooden support stand at the bottom. The “hitchhickers” would be abandoned on the roadside and their progress tracked. On the back was an address, and the suggestion to add and document where the sculpture had traveled. “When artists came into contact with hitchhickers, the project went down the drain,” said Pallas. “Artists would steal them. In New York I put out three hitchhickers on the sidewalk and within half-an-hour they all disappeared.”

While in Detroit, Johnson called Pallas and visited his Grosse Pointe studio.”He was very strange and soft spoken,” said Pallas, who made the Ray Johnson figure in his studio by tracing Ray’s silouette onto the wood and took several Polaroids to help guide his likeness. Pallas later dropped off his Johnson hitchhicker to a gallery in New York City where Johnson picked it up and agreed to hold onto it for one year. After a year had passed, Johnson refused to place the stand-up by the roadside, according to their agreement. “I just became attached to it,” Johnson told Pallas. “Johnson said the portrait was his after he added a necklace to it,” said Pallas, “and then he exhibited the work as his own.” Pallas tried to contact the Johnson estate and was told the stand-up was in a warehouse and sometime later it became lost. The hithhicker episode can be read on the Jim Pallas website.

Almost twenty years after Johnson’s death, a photo of the hitchhicker turned up in PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE: Ray Johnson Photographs (Mack Books, 2022). The photos were made during the last three years of his life. “I heard he cut it in half,” said Pallas, “It’s good that he documented it.” The photo Johnson took of the hitchhicker is set in a playground on top of a Jungle Gym. The bottom half of his body is a George Herms bunny head, from a series he called “Movie Stars,” perhaps a nod to his Book of Death, mailed out around 1963-1964. An advertisement in the Book of Death, included an 8 Person Show with Ray Johnson, George Brecht, George Herms, and a Brick Snake for Anne Wilson.

*

One of Ray’s close friends was archivist William S. Wilson, who lived in a two-story apartment in Chelsea, New York, crammed with works by his artist mother, dozens of potato mashers, and a huge Ray Johnson archive dating back to the mid-fifties. Wilson had some of the best insights to Ray. “The rhythm in some of Ray’s thinking is like breathing out and breathing in,” said Wilson, “He takes the air out of something, flattening it, and then he pumped it up again according to his own rules and desires,” quoted Wilson from Frog Pond Splash, a small collection of Johnson’s collages paired with writings by Wilson.

In the interview Ray Johnson and Fluxus, Wilson notes the importance of friendship in all of Johnson’s art, how the art functions as a type of gift symbol:

I need to think about the society of friends brought together by Ray. I note gratefully on an envelope from Luc Fierens the words, “in the spirit of mailart as a social spirit,” and “mailart is social art.” His words help to focus on the plane of moral values, rather than the “fame” or even modest recognition mailart might bring. That theme of art among a society of friends constructed by participating in art differentiates Ray’s work from the hobbyist shows to which people send decorated postcards with no intimacy, no rapport, no commitment to friendliness except in a generalized way which is sentimental because it costs little in action.

Joseph Cornell made box art for his network of forgotton ballerinas, Hollywood starlets, and his dream crushes. While Cornell was a hopeless romantic dreaming inward, Johnson was a hopeless prankster who countered sentimentality by working the art scene inside and out. Standing beside the signs of DADA with his immaterial attitude.

*

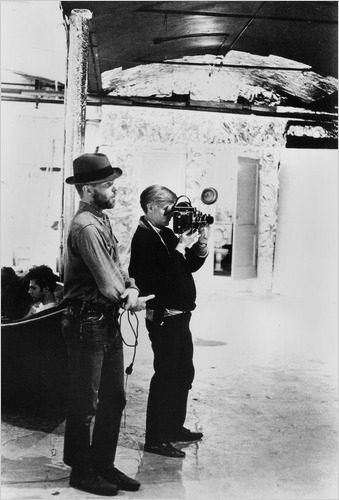

Ray Johnson holding a microphone and Andy Warhol filming at the silver factory, factory foto by Billy Name, 1965

In the William S. Wilson essay Ray Johnson and Fluxus Billy Name mentions the aura and magic of physically being near Ray, as a kind of magical contaigon set in:

… walking down the street with Ray Johnson… it becomes alive. The fire hydrants are artistically, aesthetically alive all of a sudden and part of your world and engaging with you… and all of a sudden you see the world as this wonderful, delightful, joyful, playful place and it doesn’t stop. It’s not like it’s something you get when you’re with Ray and then you go away and say ‘gee I oughta see Ray again and get that feeling.’ He was such a master that he incorporated your mind into his collage so that you became part of this joyful world that he lived… I have mixed feelings about his final act, the death scene… and I can only accept it as part of one of his art pieces because there’s no way this guy could have been emotionally driven or socially driven to do away with himself…

Johnson brought Andy Warhol to Billy Name‘s silver clad apartment in 1963, during a hair-cutting party. Warhol then commissioned Name to transform his factory studio in silver, launching Warhol’s experimental “silver age” of pop-art. Name left the factory in 1970, and Warhol gathered his belongings in his silver painted trunk. Warhol put the trunk including negatives, photos, and a group of early self-portraits into storage until 1987, when it was returned to Name after Warhol’s death.

*

Wilson wrote a brilliant piece on Johnson’s life and death for the Black Mountain journal, describing his death as a mailing event by sending himself through the water. “Ray’s body was, as I think he might also have planned to be, mashed in the process and tossed toward shore like flotsam,” wrote Wilson. The Wilson archive was donated to the Art Institute of Chicago, which also holds many of Joseph Cornell’s boxes. Wilson also wrote on Ray’s obsession with the number 13, which appeared in Blastitude 13 as: Ray Johnson and the Number 13. Johnson once ordered a dozen bagels and the baker gave him an extra one, a 13th, on the house. “I said I ordered a dozen!” Johnson yelled, throwing the extra bagel back at the baker.

[An early version of this post appeared in a Backroom newsletter from 2004]