I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unique, small press book reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired pavement inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits independent bookstores nationwide. If titles are unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Most of Mr. Bowden’s suggestions are stocked or can be ordered direct from Book Beat. Thank you for your support! Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at:I arrogantly recommend…

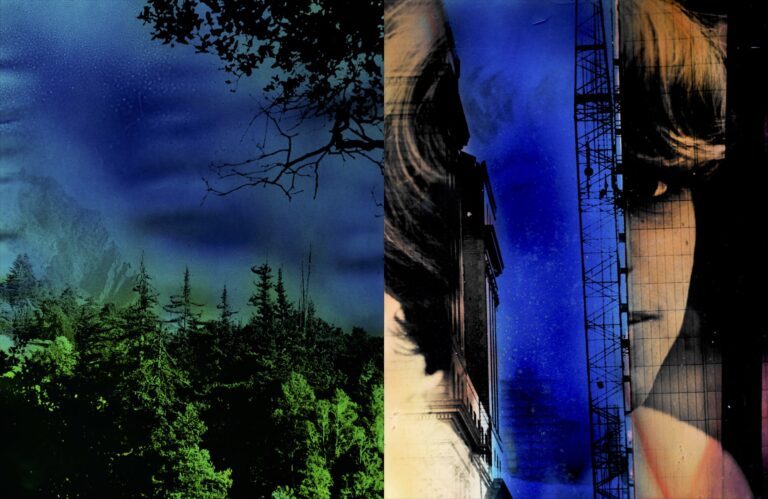

Artographer

Artographer

Kali

powerHouse Books

Born Joan Marie Yarusso in 1932, in Islip, New York, she was divorced by age 30 (as Joan Archibald) with two children. So, in 1962, she moved to Malibu, Pacific Palisades, and her mother paid for her children to be placed in boarding school while Joan figured out what to do with herself. One thing she did was take a few college classes in photography basics, including film developing. She built on those basics by experimenting with the results that could be produced on film—color distortions, superimposition, etc.—via various developing techniques. Her photographer name was Kali and she claimed to have developed 45 unique techniques for developing film. The book’s end papers show how meticulously Kali detailed her experiments and strongly indicate that the effects she created in photographs were not the results of happenstance (to the extent she could control such things).

Her understanding and practice of photography extended beyond the image developed to include the medium in which it is presented. Part of her process of developing photographs included layering negatives atop each other for multiple exposures and allowing images to float in the family swimming pool, as the chlorine (reduced to 5%) changed the developing colors. Out of the pool, while the pictures dried, she added to the photographic paper such debris as sand and would also spray paint over the images.

Even though they became deeply involved in the world of photography themselves, her children seemed utterly unaware of what thier mother’s hobby amounted to, and Kali never talked about it. Only as Kali was dying, when her daughter found thousands of pictures by her and was shocked both by the extent of her mother’s devotion to photography and also by how good the photographs were compared to the highest standards.

While comparisons to Vivian Maier are made here—unknown female of exemplary talent discovered too late—the living circumstances of the two women were markedly different, although both also seemed be plagued by mental health problems. After the death of Kali’s second husband, she became obsessed by UFOs and would photograph and enlarge stills taken from any of eight video cameras she had surrounding her house, recording 24/7. Some of that period is represented here, with a strong pulse of the eerie emanating from the grainy stills of her searching her backyard for the UFO lights she thought she saw when inside the house. (Her meticulous record keeping makes an unhappier reprise here.)

Although Maier and Kali share a predilection for self-portraits, Kali’s are often overlaid with other images and unstable regions of color. Some of Kali’s portrait images struck me as just a background on which to experiment. Vivian Maier seemed interested in the many ways in which her form could be represented in photography. Kali is interested in altering and permutating the perception of it, hiding, revealing, suggesting, juxtaposing, and layering.

While her photographs certainly are of the time—the psychedelic ‘60s and the rainbow-hued colors used to represent hallucinations—they don’t feel dated but instead feel emblematic of a time and place, as it could be said of painters and paintings from the Delft school. The pictures are posed—candid and street aren’t her thing—perhaps in knowledge that the shot will comprise only one of several levels which together will be manipulated in various ways. Perhaps the seeds of her future dissociation were here.

Artographer—a term Kali invented and copyrighted—makes a strong case for Kali as a photographer—an artographer—who did much to expand photography’s possibilities and technical range.

Visit KALIARTPHOTOGRAPHY, a website devoted to her work.

Life Among the Aryans

Life Among the Aryans

Ishmael Reed

Archway Editions

Ishmael Reed’s 3-act play, Life Among the Aryans, targets life in racist America during the Trump era, although it’s of a piece with Reed’s 50 years or so of parodying American racists and con artists, and Trump is merely their most prominent poster child. In Life, two disenchanted white men start following Leader Matthews, a racist con artist, who, of course, demands more and more money from his acolytes for various projects that never materialize. The main difference between yesterday’s and today’s cons seems to be that the con is nastier than ever, as suggested by this phone conversation one of the white men has:

John: O, hi David. (Pause.) No I told you that I don’t do that anymore. Every time I think about my former trade, I get depressed. Leader Matthews convinced me that my life has a higher purpose. To restore the America that I grew up in. A place where the Dad sat comfortably in a smoking jacket, feet propped up on a stool while reading The Saturday Evening Post. The dog fetched your slippers. Christmas trees were green. And your spouse spent all day in the kitchen preparing a pot roast and if the kids got out of line, you smacked them one. I’ve stopped selling bootleg porn. (Pause.) . . . Look, I’ve dedicated my life to making America Great Again. Saving what remains of Western Civilization. Staving off the barbarian hordes. Standing firm against a country that is on the road to perdition. Same-sex marriage, Hip Hop, Black Lives Matter, people refusing to stand up when the Star-Spangled Banner is played. Leader Matthews gave a long list. Sorry, David. I have a new life. I have Higher goals. (Hangs up.)

Michael: Who was that?

John: David Duke. He thought that I was still peddling bootleg porno.

While Matthews is drumming up financial support, Congress announces that it will pay reparations of $50,000 to every Black man, woman, and child in the country. Enter Dr. Krokman, a Black “doctor” who has a formula (stolen from a Black grad student) for an injection that transforms white people into black. Racism is one thing, and money another: Whites gladly get line for a shot that will transform their bank accounts from a hole in the pocket to $50K. How far will the women caught in the crosshairs of this nonsense put up with it, and to what effect? Philip Roth allegedly stopped writing comedies in the 1970s when he realized that Nobel Committees don’t award humorists. The U.S. judicial system has been a world model for oppressive governments since at least the Nazis, who sent their top legal scholars here to figure out how we do it, so they could import the practices back home. (Some Nazi scholars found certain U.S. racial practices a bit too much even for sensible Germans back home.) What else could be obstructing Reed’s path to a Nobel Prize but the Committee’s refusal to acknowledge the grim realities of everyday life expressed through humor?

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes

In a Time of Panthers: Early Photographs of Jeffrey Henson Scales

In a Time of Panthers: Early Photographs of Jeffrey Henson Scales

Jeffrey Henson Scales

powerhouse/SPQR Editions

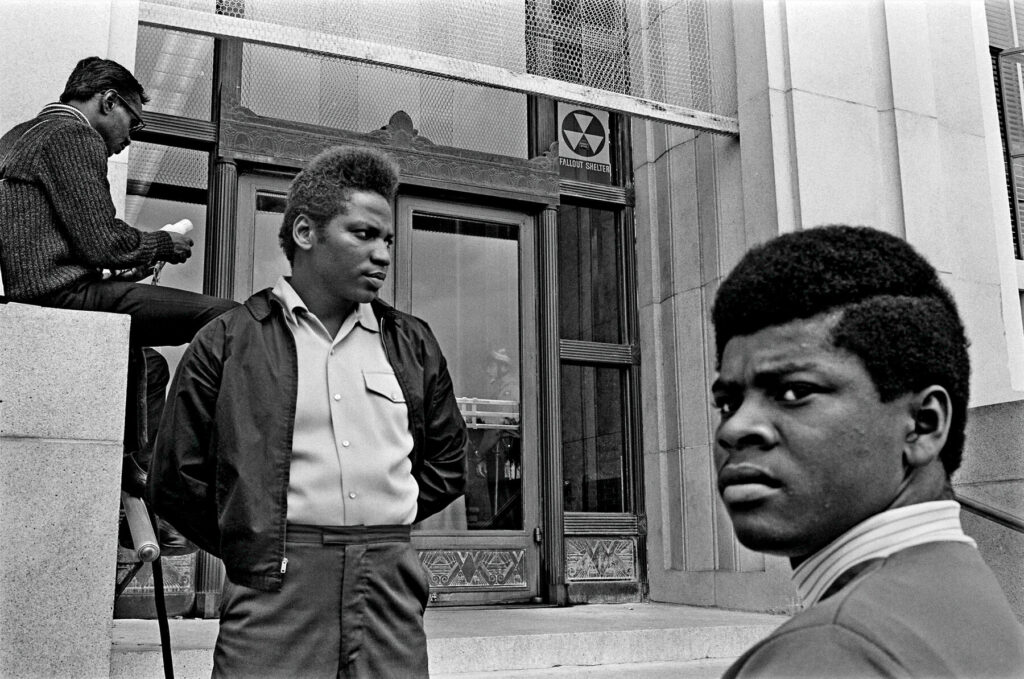

From ages 14 to 16, Jeffrey Henson Scales had the good (if fraught) fortune to be anointed house photographer to the Black Panthers of San Francisco. In 1967, when Scales was 14, after a summer tour of relatives’ homes across the U.S.—seeing first-hand such uprisings as those in Detroit—he decided to apply the interest in photography he’d had since age 11 to the local scene. Soon, Scales was both in the streets and up-close-and-personal with H. Rap Brown, Bobby Seale, Edlridge Cleaver, Stokely Carmichael, and others, documenting public reactions to the Huey P. Newton trial, the demonstrations, and police provocations. An excellent record of the time.

A Beautiful Ghetto

A Beautiful Ghetto

Devin Allen

Haymarket Books

When citizens of Baltimore rose up at the murder of Freddie Gray (whose spine was severed enroute to the police station), Devin Allen was a young, self-taught photographer and native Baltimorean who knew how to navigate the city’s streets and where things were going on—“things” being demonstrations, cook-outs, people just hanging out, and scuffles. His insider view of the panorama of reactions to Freddie Gray’s death landed his photographs appearances in Time and New York magazines as well as other outlets. Over 145 pages—interspersed with bona fides from Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Wes Moore, and others, as well as poetry by Tariq Touré—he shows the Baltimore of that time as a place of rough beauty; a materially impoverished place where non-material bonds of friendship, kinship, and love exist, nonetheless; and where people will again confront the civic power that too often abuses its authority at the expense of human lives.

Divine Blue Light

Divine Blue Light

Will Alexander

City Lights

Will Alexander (finalist for the 2022 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry) writes metaphorically and syntactically rich poetry dense in compound adjectival phrases, creating a world view that poetizes the forces at work in life (biological, historical, and linguistic) and works of the imagination as simultaneous at all levels of material and non-material existence, quantum to galactic, organic and technical. It’s turtles all the way down, up, and out. But what turtles!

Here are the last lines of “Anterior Cartography”:

suppression has cast its lot upon our neurological realm

& so it appears that the hieratic has tilted toward allowing other conditions to combine

& they inscrutably rise above telepathic claustrophobia

as shifts in one’s signaling that transpire & re-combine

according to the deftness of dice & anathema

as protected combinatorial combustion

so that perhaps an Oryx speeding through a wetland will furtively amaze itself

via its chronically imposed cellular limit weaving in & out of itself so that it alchemically transmutes eternity

Not easy reading but one that rewards study at a slow pace.

It’s Life as I See It: Black Cartoonists in Chicago, 1940-1980

It’s Life as I See It: Black Cartoonists in Chicago, 1940-1980

Dan Nadel (Ed.)

NYR Comics

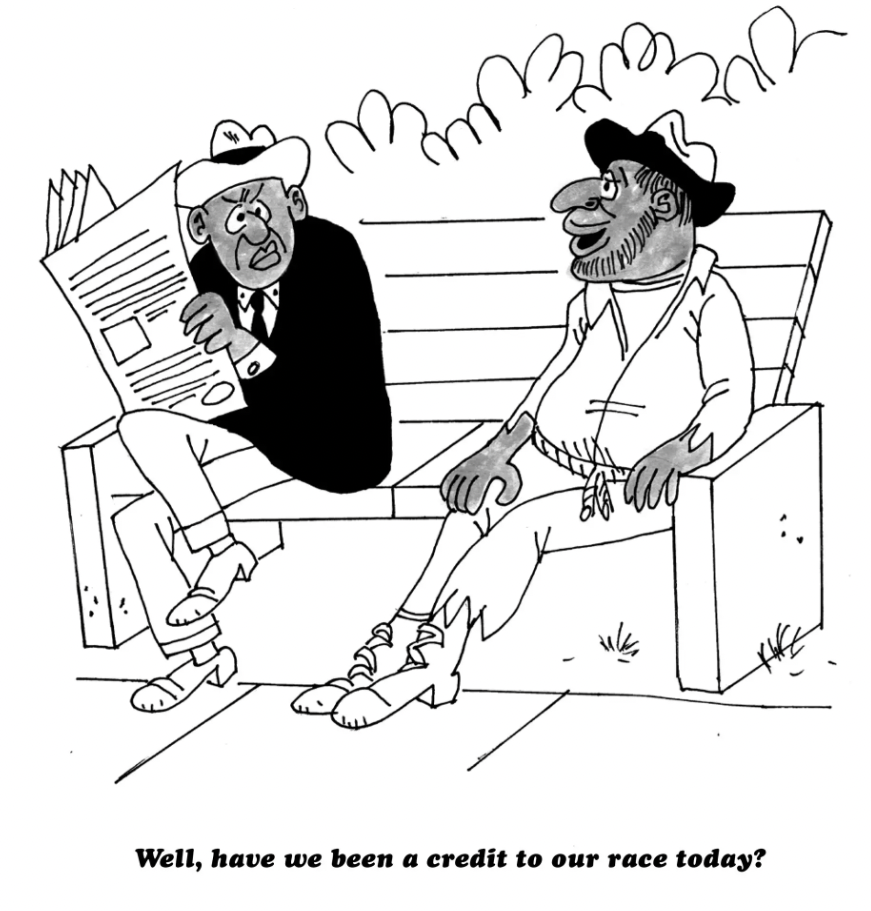

It’s Life as I See It: Black Cartoonists in Chicago, 1940-1980 is an anthology of strips and panels by Black cartoonists prominent in Black-owned and -targeted newspapers and magazines of the mid-20th-century. Tom Floyd, Grass Green, Seitu Hayden, Jay Jackson, Charles Johson, Yaoundé Out, Turtel Onli, Jackie Ormes, and Morrie Turner—the cartoonists represented here, each prefaced with a brief bio—were largely locked out of illustration and cartooning jobs in more widely available media (such as The New Yorker). Exceptions include Johnson for his novel The Middle Passage and Turner for his “Wee Pals” strip, but these were cartoonists whose first professional appearances began toward the end of the period covered here.

Not surprisingly, the content often deals with subjects white audience didn’t want to confront—the moral hypocrisies of racism and Black cartoon characters that didn’t act according to white stereotypes. (In contrast, Andy Capp—a strip about an alcoholic wife-beater—was perfectly fine for white children to read and laugh at.) The content also deals with (non-political / -racial) social and domestic issues, like any other comic strip, but from a viewpoint not usually found in comic strips of the period. And there is the science fiction / Afrofuturism of Turtel Onli’s “NOG, Protector of the Pyramids” and the alternative history of “Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos” (which should be a band name) by Jay Jackson. Each cartoonist brings with them their own style and terrain, none trying to be the next [name of famous cartoonist here] but just themselves, and in so doing finding they had much to say for audiences of similar backgrounds and concerns.

All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End: The Cartoons of Charles Johnson

NYR Comics

The works of Charles Johnson—perhaps best known as the author of Middle Passage, which won the National Book Award—have been recognized in numerous ways, including a MacArthur Foundation fellowship, an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature, and other awards. These acts of acknowledgement of Johnson’s talents came after he earned his PhD in philosophy while—wait for it—working his way through college as a cartoonist. The cartoons were largely single-panel gags concerning racial issues published in Black-owned media outlets. A selection of Johnson’s early cartoons was published in the anthology It’s Life as I See It, and this book follows up on that initial selection, with almost no overlap. Unlike the previous anthology, which ends during the 1980s, All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End includes works long out of print, lost and restored, and never before in print, ranging from Johnson’s first published cartoons in 1965 and to present examples done gratis for small publications. Topics range from radical Black Panther actions to Stanley Crouch’s dismissal of Spike Lee and Toni Morrison. An essential collection.

The Strudlhof Steps: The Depth of the Years

The Strudlhof Steps: The Depth of the Years

Heimito von Doderer / Vincent Kling

NYRB Classics

Sex, slaps, scandal, suicide, public humiliation, purloined documents, duplicitous twins, contraband, and more across 14 years and 800+ pages, Viennese Modernist style. Warning, intrepid reader! The print is small and the paragraphs long. I clocked in at about 24 pages per hour, but the long slog is rewarded by the omniscient narrator’s tone, cynically ironic à la Claude Rains’s character, Captain Louis Renault, in “Casablanca.” Two main sets of actions occur, before and after World War I, with Vienna’s Strudlhof Steps serving as the social nexus for the novel’s large cast of characters. (Begun in 1940, the novel was unpublishable until 1951 due to Doderer’s earlier membership in the Nazi Party.)

Much like Charles Dickens’s novel-writing practice, Doderer introduces new characters and incidents throughout the first half of the book, then in the second half starts tying together the various strands, leading to a climatic ending with satisfactory outcomes. (Before that happens, though, the book can confuse as descriptions of one character segues into another—what begins with a parenthetical aside about a new character suddenly becomes a 20- or 50-page set piece about that new character, before segueing to the next character, with little overlap among characters and incidents during the first half.) The upshot, though, is the moral and intellectual growth of one character, Meltzer, in his transition from military to civilian life as he overcomes the terror of war (only lightly touched upon, despite its significance) and can think beyond his mere capacity as a government functionary.

Doderer offers shrewd analyses of characters and their motivations, and the stupidity of those characters and motivations in ways that are not immediately obvious. (Daniel Kehlmann tells us, in the Afterward to this novel, that Doderer came to see his involvement with the Nazis as one of those tremendous acts of stupidity, without ever publicly disavowing his admiration for Hitler. René Stangeler, Doderer’s fictional stand-in here, while one of the novel’s smartest characters is also attacked by the narrator for his stupidity.)

Combine late-period Henry James with Robert Musil of The Man without Qualities and you’ll have a notion of the level of detail, nuance, irony, and moral disappointment at play in The Strudlhof Steps, minus any clear notion of where the book may be headed at any given time, and with plot surprises thrown in along the way during those few points in which an approaching narrative destination may be discerned. Doderer’s strongest talent as a narrator is his sense of metaphor, which gives much of the novel its psychological energy. Usually the metaphors come in sustained salvos, but sometimes they are as concise as this chestnut, in which one character is described as “far less a person than an illness which certain organisms must endure.”

At one point about a third the way through, Doderer combines, in his description of Thea Rokitzer (Meltzer’s future love interest) metaphor with what translator Vincent Kling renders as a cross between Ogden Nash and proto-Beatnik:

She was missing two traits needed to attain stupidity as our age recognizes it; they were brazenness and hostility, neither the faintest trace of which was evident in her face or her person. One might, accordingly, call her callow. Very well. Call callows shallow, but though soft as a mallow, it’s not fallow. No, it’s a bud that arose when the sp[ring sun’s warmth grows and falls low on the callow in the hollow while the cow lows, a bud not just in the physical sense, the kind, for example, that René Stangeler, his hand skillfully guided, had in earlier days learned to find under Editha Pastré’s unbuttoned tennis shirt. . . It was to blow in that one furrow (unfallow) her callow being would show, but for her it really was a slow go (but then she’d so glow) rather than a no-go, and there was more to her than you know; so what ensued for the time being, though only in the summer of 1925, was the low blow of the captain’s entry . . . through the natural gateway. Yet for all that, if we were forced to make a choice, we would prefer to opt for the assertion that Thea was far from stupid.

A long, strange trip, but definitely worthwhile. Perhaps NYRB may be induced to re-release Doderer’s follow-up novel, The Demons, which is longer by half than Strudlhof.

Poguemahone

Poguemahone

Patrick McCabe

Biblioasis

A 600+ book written as a poem but reading like a novel about Una and Dan Fogarty, children of the unwed Dots Fogarty, a suicide, raised in an Irish orphanage / foster care system that seems to blend the worst aspects of juvenile prison with factory work. But the book mainly focuses on their later lives, in the early ‘70s, when Una is in her 20s and free of the orphanage, living for the summer in a hippie squatter commune where—among the dope, liquor, acid, and changing personnel—she falls in love with one Troy McClory, a college-semester drop-out and Ian Hunter / Mott the Hoople acolyte, who gives her the attention she otherwise never received or receives—even if this means he occasionally beats her.

Dan Fogarty narrates the story, the broken lines on the page capturing the cadence of his speech (blank verse, no ABAB here). But as the narrative goes on, certain facets of the Dan-POV don’t quite add up until, about mid-way through the book one’s hunches are confirmed (spoiler alert) that Dan is actually a gruagach, an Irish sprite that is invisible and unheard (to all but Una), with poltergeist-like abilities to move objects—such as pushing out the window a competitor for her Troy’s amorous attentions. A gruagach embodies a soul—Dan’s case his soul was limited to the few drops of blood that dripped from his mother’s uterus after a botched abortion, while she hanged herself from the rafters.

Traditional Irish folklore would say that Dan was a gruagach who put bad ideas into his sister’s head, just as Una claimed; whereas modern medicine would say she’s schizophrenic. Dan himself claims to suffer from “inmí,” an Irish term for depression and anxiety, which often results in violent drunkenness. “Poguemahone” is another Irish term, meaning “kiss my arse,” which suggests something about the book’s narrative tone. Some of Dan’s physical nastiness is directed to those who debase his sister, who, on top of being dim and delusional, is also obese, which attracts to herself unkind attention that mere dim and delusional do not.

When the book opens, circa 2019, Una is 70 with dementia and in a housing facility that can meet her needs. Like it or not. This is the medias res the narrative returns to during the book’s final hundred pages, as Una prepares her final stage production, just as she had in the days with Troy and Dan. As with her stage productions of the ‘70s at the Mahavishnu Temple, the emphasis is on the verb “prepare.”

Poguemahone, for all its comic moments, is more seriously about the tensions between traditional and modern ways, memory and vengeance, and British / Irish power dynamics.

Astra: The International Magazine of Literature, Issue 1

Astra: The International Magazine of Literature, Issue 1

Founded by Nadja Spiegelman, daughter of art spiegelman (author of Maus) and Françoise Mouly (art director for The New Yorker), Astra is a new biannual 200-page anthology of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, art, and comics by writers, translators, and artists from around the world, some better-known than others, including Don Mee Choi, Fernanda Melchor, Terrance Hayes, Ottessa Mosghfegh, and many others. Printed on heavy-stock paper with richly colored illustrations, Astra presents itself with the brash confidence of a fashion and lifestyle magazine but with substance replacing flash. Ultimately, quality of artistic merit trumps production values, of course, but it’s nice to see good writing and cartoons outside of periodicals with budgets akin to an unwanted step-child’s allowance.

Typo: Journal of Lettrism, Surrealist Semantics, & Constrained Design, #1

Typo: Journal of Lettrism, Surrealist Semantics, & Constrained Design, #1

Black Scat Books []

Nerd alert. Typo: Journal of Lettrism, Surrealist Semantics, & Constrained Design is the first in a promised (irregular) series of anthologies devoted to oddities of typographic design history, extending from now to the 1400s, including mnemonic devices, “Forty-Five First Letters” (they’re real!), “Surrealist Sign Language,” asemic writing, and lots more from Doug Skinner, Norman Conquest, Raymond Queneau, Isadore Isou and other contributors. Visually fun to look at and filled with interesting historical factoids about printing.

Baby Boom

Baby Boom

Yokoyama Yuichi

Breakdown Press

Japanese cartoonist Yokoyama Yuichi creates visually compelling stories having little to do with sensible plots and more with geometric shapes and lines that endlessly vary—including and especially talking shapes of humanoid form. What matters more than plot are the angles, proportions created by the lines and the sense of speed and motion, de-familiarization and disorientation they create within their readers.

Baby Boom replaces Yuichi’s previous hard-angled SF weirdness with looser lines describing what look like parent-toddler interactions composed of felt-tip marker lines in two- and three-colored layers. (In Yuichi’s interview with the book’s translator, Ryan Holmberg, he claims his original intention was to draw all panels in one color, which would have made most of this book unnecessarily difficult to de-code.) Episodes include “Pet Shop,” “Pool,” “Fireworks,” “Playground,” “Rain,” and other topics that at age two don’t yet feel mundane. The lines, compared to his earlier works, are looser as are the moods conveyed—joyfully domestic rather than tensely intrepid—, and he successfully transplants his usual alienated geometries to real-world activities. Baby Boom is an excellent book and one that perhaps marks a transition in his evolving styles.

Juan Hormiga

Juan Hormiga

Gustavo Roldán / Robert Croll

Elsewhere Editions

In this picture book for children 5-8, Juan Hormiga is a lazy ant with a vivid imagination. Because the stories are so vivid and exciting that he tells of his grandfather’s adventures, the other ants give him a pass on his lack of foraging. Then one day, Juan decides to live rather than tell his grandfather’s adventures, and off he goes. At this point the story becomes an argument for the collective uses of fiction and wonder: The ants in Juan’s community re-tell each other aloud the perils he must be confronting, based on the stories of his grandfather that he’s told hundreds of time and that they have internalized: Step by step, catastrophe after catastrophe they imagine, until—the ants assume that Juan must surely have died. Is it possible?

What is Love

What is Love

Manuel Magallanes Moure / Jessica Sequeira

Snuggly Books

Four stories of love by a Chilean writer of the early 20th century. Jessica Sequeira, who provides the compulsively readable translation of these stories, also writes the book’s afterward, providing a brief biography of Magallanes Moure, including a description of his role in Los Diez, an important cultural group of the time, an amorphous association of artists and writers from various fields, beginning in 1916, and his occasional hot-and-heavy epistolatory exchange with Gabriela Mistral, who won the Nobel Prize for her poetry in 1945.

Although Sequeira never mentions Balzac as an influence, it’s Balzac’s approach that Magallanes Moure seems to take to his writing: To explore nuances within a person’s emotional life. In the case of Magallanes Moure’s stories, the emotion is love—which imbues their protagonists with a variety of values, desires, wants, and needs in conflict with each other—each value, desire, want, and need with its own validity, each with its own undesirable results. The nuances of the protagonists’ emotional life are then set in a real-world context with real-life constraints, within which the protagonists must negotiate their way to conclusions, whose results will necessarily be ambiguous.

From “The Desire”:

Soon the cold atmosphere surrounding us went about warming. We started to get to know each other. In her conversations, very delicate and also very simple, Irene let me glimpse more than once the sadness of her life beside that man who didn’t understand her, didn’t respect her; who no longer felt even admiration for her beauty. He was a practical man, absolutely deprived of sensibility, deprived of all emotion that wasn’t about making a good deal in the stock market, always worried about supply and demand, with no aspiration but to make a lot of money. One of those men, in short, who like the brute Esau, are capable of selling, I won’t say birthright, but even honor, even what they once loved, for a fistful of ninepence banknotes. . .

Relocations: 3 Contemporary Russian Woman Poets

Relocations: 3 Contemporary Russian Woman Poets

Polina Barskova, Anna Glazova, Maria Stepanova

Zephyr Press

Catherine Ciepiela gathers poetry from three prominent Russians, Polina Barskova, Anna Glazova, and Maria Stepanova. Ciepiela, who also translated Barskova’s newest books, Living Pictures (NYRB, 2022), and is joined here by translations from Anna Khasin and Sibelan Forrester. In this bi-lingual collection, Relocation’s introduction provides succinct biographical information and descriptions of each poet’s methods and interests (poetess’s, in the case of Stepanova).

Ciepiela notes that Barskova’s poems—made from scraps of diaries, journals, and other written ephemera during the time of the siege of Leningrad—are deeply uncomfortable reminders of the realities behind a span of time that Russians otherwise sentimentalize and heroize—assuming the time is remembered at all. From “V.V. and N.K.—Monument”:

I won’t not for anyone

Grab or give up

The darkness at dawn for the darkness at dusk,

The gew-gew and meow-meow of Leningrad’s lost,

The crystalline quiet—bruit de silence—

Just before the explosion, and after—the shell of the vanished house

On the street corner vanished in smoke and dust,

Where I sat on the floor and read you and read to you once.

Anna Glazova is terser and opaquer than Barskova, meditating on moments rather than days. From “Laws”:

prayer

make a wolf

be wolf to human

make red patches of shame appear

under the skin over the heart when you are looked at

Maria Stepanova’s poetry deals with everyday, common experiences, often in the voices of the characters narrating her poems. In “The Pilot,” the narrator comments after each stanza phrases like “But that isn’t anything yet” or “But life just kept on going on,” a life of every-diminishing returns:

When he returned from there, where,

He yelled in his sleep and dropped bombs on cities,

And ghosts would appear to him,

He would get up to smoke, and would open the window,

The shared rags lay there in a heap,

And in the dark I gathered my bundle.

Some of Russia’s best poets these days are women. Relocations is just a small, recommended introduction to that world.

Identity Pitches

Identity Pitches

Stine Janvin and Cory Arcangel

Primary Information

Stine Janvin and Cory Arcangel put before themselves the task of setting to music the three weaving patterns most common to “traditional” Norwegian sweaters (the designs trace back only to circa 1850, hence the scare quotes). Janvin and Arcangel came up with an elegant solution amply illustrated in this book of only 74 pages. Alas, no links to performances are provided but an ambitious group of readers could assign each other sounds to make/play, then play the scores provided here, and settle into the musical warmth of an aural Norwegian sweater.

Critique of the Gotha Program

Critique of the Gotha Program

Karl Marx

PM Press

Karl Marx’s essay, “Critique of the Gotha Program,” takes up only 37 of this book’s 99 pages, including footnotes, and is bracketed by Peter Hudis’s introduction and Peter Linebaugh’s afterword, which fill the remaining pages. Hudis both places this obscure essay in the context of Marx’s other writings on labor and corrects prevalent misinterpretations of Marx’s view of the historical trajectory leading (presumably) from capitalism to communism—misinterpretations introduced by Stalin, under whom the Soviet Union largely retained Russia’s pre-existing capitalist system. The other error of Stalin’s Hudis wishes to correct is that Marx did not distinguish between socialism and communism and instead used the words as synonyms throughout his works. That is, socialism is not a step toward communism, as the typically inept Stalin would have it, but is the same thing. Marx’s purpose in writing his critique was to offer a corrective (pre-Stalin) to competing methods for bringing about a communist society, methods, Marx felt, to be no better than what the mass of world societies suffered under capitalism.

Critique of the Gotha Program is perhaps better seen as a negative example of what communism isn’t—that is, although the Gotha Program that Marx criticizes purports to serve communist ends, Marx easily demonstrates that the document’s key terms are ill-founded and defined, representing what communism is not, let alone how it is achieved.

Apart from that, Marx’s Gotha Program critique is a notable forerunner to ecologically minded anti-capitalist screeds: “Labor is not the source of all wealth [contra the Gotha Program’s claims; Marx’s italics]. Nature is just as much the source of use values . . . as labor, which itself is only the manifestation of a force in nature, human labor power.” By insisting on nature as equal to labor as the source of material wealth, Marx acknowledges nature and its resources as equally alienated by the forces of capitalism.

Very excited to find out about The Backroom. Wish I were six or seven people so I could read most of the books you recommend, being a big fan of complicated poltical fiction ala aka Victor Serge, Stefan Heym, Ousmane Sembene, Dr. Faustus, Death of Virgil, Life and Fate etc., etc., have you checked out some of the Eastern European Serbian and Croatian writes like Dasa Drsik EEG BELLADONNA and Dubravka Ugresic Ministry of Unconditional Surrender, Blue Fox??? I’m also a lifetime student of African American Literature. I have lined up to read James Hanrahn’s first book, John Edgar Wideman’s latest book of short stories, Perceval Everett’s The Trees, and a brand new book just out about a feisty black feminist professor who tracks down a white supremacist kidnapping black girls and secreting them away- it looks like that rarity- a politically sophisticated but noholdsbarred thriller, like a shorter Leonardo Padura thriller ( I Loved the Man Who Loved Dog but it’s dam long All these dam novelists who go onan on Marquez included need to check out the novels of Ronald Fair, and Ernest Gaines, Chester Hime’s underrated thriller RUN MAN RUN. I will be in touch the next few days, if you google my name you can fnid some of my poems andd stories. My one published book is out of print; I Looked Over Jordan and Other Stories.