Photographs from Detroit 1975-2019 (Ohio University Press, 2022) is a book by photographer Bruce Harkness and edited by John J. Bukowczyk. Most of the content was taken between the mid 1970s and late 1980s, from three series; Cass Corridor, Poletown, and Urban Interiors. A variety of engagement including portraits, architecture, street photography, the urban landscape, and some joyful exploring are presented across 170 large-format images finely reproduced. The set mood is often dark, formal, intimate, and respectful. Harkness offers the viewer a strong defense of human dignity and the urban experience. The photos are centered on details, and the qualities that make black and white photography unique. He’s an empathetic, emotional, investigative photographer -lifting up his subjects in every situation. His style is unique with direct traces back to the heights of modernism, where little is ironic or insincere. Harkness is among the best contemporary photographers documenting Detroit, and this new collection is ample proof. Signed copies of Photographs from Detroit 1975-2019 are available in the Book Beat gallery.

An Interview with photographer Bruce Harkness

All photographs are ©Bruce Harkness and are reproduced here with the photographer’s permission.

Beside the workmanship, there’s a lot of preparation and precision that goes into making your images. What do you look for when making a photograph? What makes a successful Bruce Harkness image?

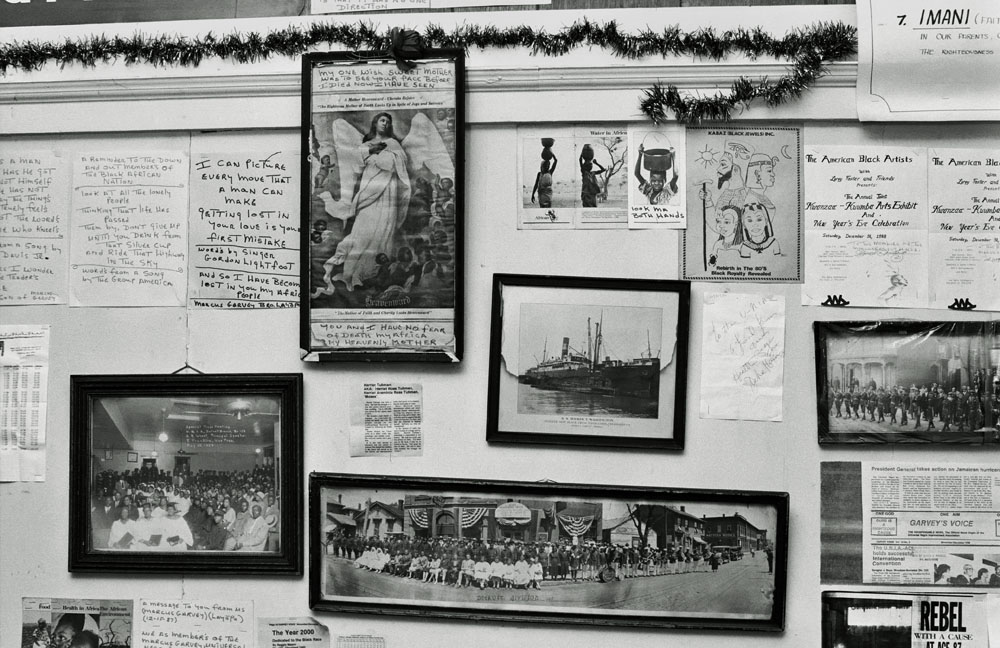

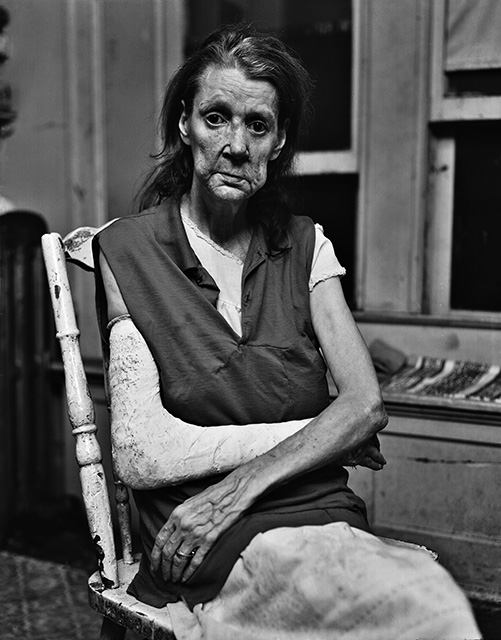

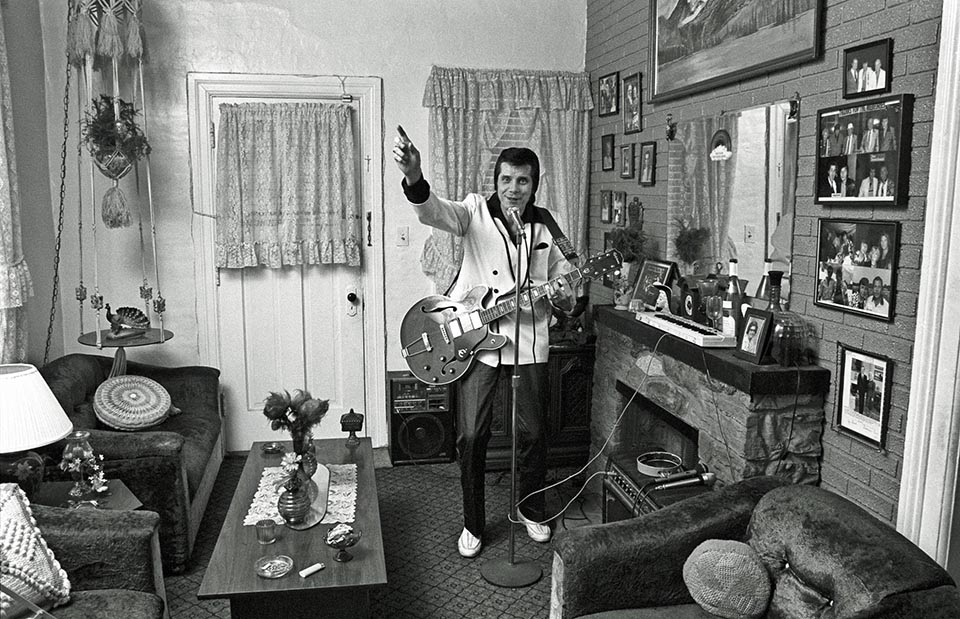

The images you refer to seem to refer primarily to the interiors from the 1970s and 80s. In these I am interested in the detail of things. I want to reveal aspects of a person’s life and interests, and this is often found in their possessions and the arrangement of these possessions. Personally I find small details fascinating so am mindful of looking for these objects when I photograph. These particular photos are very different from photos that are about design or space. Although I appreciate this type of photo, and have made a number of them, my interiors, and some exteriors as well, have to do with content. You do not take in these photos with a glance from several feet away, one must go in and get close to them, even use a magnifying glass to help reveal detail. There is information in these photographs, often writing, and there is something to be learned from these images. This is how it is with the photos taken in the U.N.I.A. office, there are all sorts of things on the walls, including readable text. Upon careful observation one realizes that the person who decorated the office walls added his own words and quotes. I suppose we as photographers, or artists, if you must, find certain things beautiful and meaningful. I find the things other people, often anonymous people, make or collect very beautiful and meaningful even beyond their own lives. My photos are in a sense an anthropological study, an inventory of what other people, sometimes very different types of people, find significant and useful. It is also true that this kind of photograph is the type of image I have always found most interesting – work by Eugene Atget and Walker Evans, and painters and writers also who have depicted or described the way things look. I was a student and close to Bill Rauhauser for a time. He advised me about the work I was doing at the Niagara Apartment in the Cass Corridor in 1978. When I showed him my interior portraits from the apartment that I planned to submit to the Detroit Free Press, he suggested that to flesh out the story I include a photograph showing the exterior of the building, which I then took and added to the submission. The Free Press published the article. Bill used to talk about Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of things Past, and talk about how beautifully Proust described the look and feel of items and rooms and places in the story. These small items in people’s lives are so beautiful and fragile and transitory, yet so full of meaning and significance. The photograph, as it does for so much, preserves these things.

I’m wondering if you believe the documentary model of photography can produce social change—and if so, how?

I think it takes a lot more than a photograph or even a life’s work in photography, to effect real positive change. I think it naïve when a photographer says he or she wants their work to help make the world a better place in which to live or to teach people how to think differently. Think how many well intentioned photographs have been made and how little they have changed the course of events or the way people think. But still, photographs, because they can show us the world as it really is, serve as a vital tool in the tool chest if the work is honest and clear. This is one of many possible goals of the photographer, along with all other disciplines – writing, painting, performing arts, poetry – to all work together to chip away at ignorance and indifference. All we can do is keep at it, hone our message, and hope some will pick up on it and perhaps alter their views in a way as to make the world, or their neighborhood, or their home, a little better place.

Does the black and white image hold special meaning for you? Do you shoot in a similar way today as you did in the 1970s?

I have always preferred making black and white photographs to making color photographs. Although I certainly appreciate color work and find much of it quite wonderful, the first images I was drawn to as a young student were those made by photographers who worked in black and white. There is something about the graphic quality of it, the way it removes a layer of distraction and simplifies the subject that appeals to me. It is difficult to put in words, but also obvious in a way. I like black and white films. I like the look and mystery of them. Black and white reduces things to lowest terms, or if not lowest, lower terms, and makes the action perhaps easier to understand, simpler. It is a more direct language. And I just love the look of a black and white print. It does not have to be a perfect Ansel Adams type print, although these are magnificent, it can be a grainy, imperfect image like some I have seen by Robert Frank. One can almost feel the texture of objects in those images. I love the grey scale. Black and white does with the subject what poetry does. It speaks to us more directly. But… I have also made color images. Sometimes with my digital camera I switch back and forth between the color and black and white setting, even during the same shooting session. Some subjects just ask for color. I think it may be more challenging to make a successful color image. Black and white eliminates the layer of potentially discordant color… ugly or distracting colors for instance. In black and white there is one less thing the photographer need be concerned with, if he or she is concerned at all. I personally still most often shoot in black and white, much as I have done for decades. Photo jobs are of course almost always done in color, as was almost all the work I did as Photographer for the City of Dearborn for twenty years. I believe Dave Jordano’s Detroit Nocturne is an example of the masterful use of color.

Can you talk about your longtime working relationship with editor John J. Bukowczyk? You both acknowledge each other’s influence, and I was wondering if this book was the culmination of those years of collaboration-and what do you think made Buckowczyk a good choice as an editor of your work?

I have known and been friends with John J. Bukowczyk for about four decades. He is really the only person who has had an abiding, enduring, interest in my photography. I think this was initially because of the subject matter I photographed. In the early 1980s we were both doing work relating to the demolition of the Poletown neighborhood for the new Detroit-Hamtramck Assembly Plant. We were introduced by the photographer Carla Anderson whom we both knew. John helped secure funding for an exhibit and donation of my Poletown photographs (1981) to the Wayne State University Walter Reuther Library. It was John who came up with the idea for the Urban Interiors Project (1987-1990) and he who again raised funds for it and directed it. This was an important photographic project in my life, and produced an important set of photographs of life on Detroit’s near east side. Of course we have not always agreed on things, but we have always been able work through our differences. I have relied on John’s methodology, or way of doing things, over the years. He is knowledgeable and exacting, and I am too often too much the opposite, although can be when absolutely necessary, and often John let me know when it was time for such. John is wonderfully intelligent and decisive and correct and capable of moving things along whereas I could go over and over choices made and make constant revisions. This is no way to get things done. John has a special eye for connections between photographs and is very good at sequencing a large body of work. This is difficult for me to do for several reasons, one being my closeness to my own work. He has said on a few occasions that I have in some way been a good influence on him too. I am sure I have in some way but one would have to ask him in what way. But it has been a very good and enduring relationship. Together we have produced several very worthwhile projects, photographic as well as written. I could not have done it without him.

I enjoyed reading your notes about the photographs and thought that was one of the best aspects in the book. They were very detailed as were the captions and I’m surprised how you keep track of time, place, and those often incredible stories. How important are these notes in your practice, and how do you keep it organized?

First of all, I have a very good memory for the little things I did years ago, what was said or done, and when. Or at least I believe I do. I think this is because of the nature of what I did, and how I moved about, so every experience was new and poignant and therefore stuck in my mind. In some cases things were written down. I recorded (on a tape recorder) the stories told to me by the residents of the Niagara Apartments, and these recordings I transcribed. These quotations were then used by the Detroit Free Press in their 1978 article about the Niagara. Unfortunately, the original tapes and transcriptions are long lost. I remember borrowing from Mary Caffery letters that had been written to her by her daughter who lived in the south. They were sad and somber letters, about how she missed her mother and the difficulties she was having in life. I stitched similar phrases of these letters together to make one, long poetic sorrowful lament and presented it to my poetry teacher at CCS. She thought it was quite excellent. But it was lost. When I photographed in Poletown in 1981 I carried a notebook and recorded the location, date, and direction I was looking for each photograph I took. All the voices and stories from subjects of the Urban Interiors project were recorded on a professional tape recorder and these tapes still exist, along with new, digital versions (on CDs) and full transcriptions. Back in the days of film, after processing, all negative strips were placed in sleeve pages and filed in three-ring binders. I have eleven such binders for the pictures I took during the Urban Interiors project. I also have binders for Cass Corridor and Brush Park images, as well as miscellaneous Detroit images. All 4×5 Poletown negatives are kept in individual archival paper sleeves which are stored in archival boxes. I usually photographed in a certain area during a certain time. There were times when I would just start out and wander to new places. I can’t say exactly where the pictures were taken when I did this unless there is some recognizable landmark in the photo. I should have made notes during these walks, or photographed street signs, but failed to do so. So the captions for these images state near or in the vicinity of. With my kind of photography it is very important to take notes. I am not a very organized person. I admire those who keep their material well organized and annotated. In the end it makes life a lot easier.

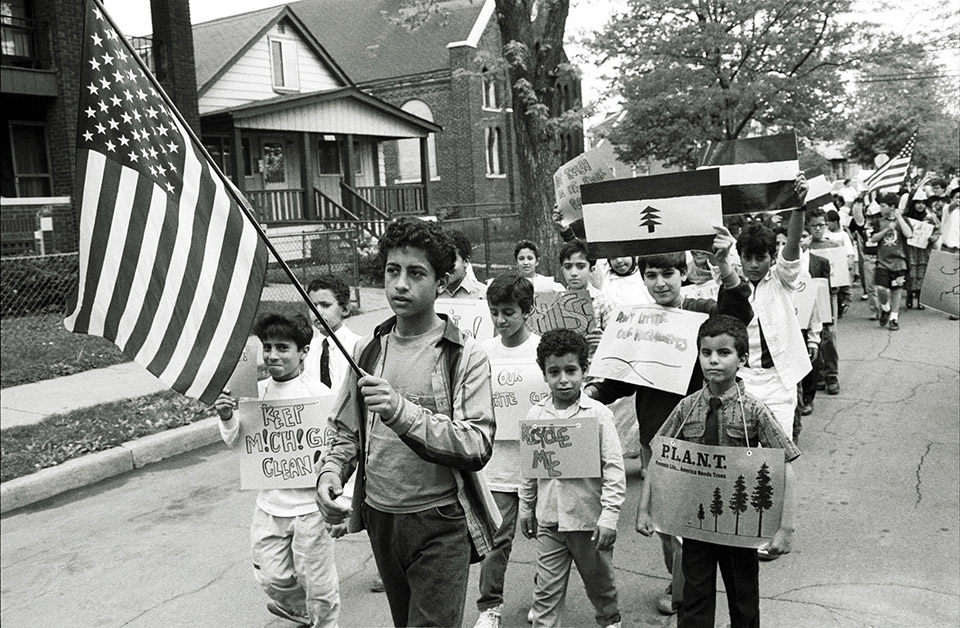

Near the end, the book suddenly shifts gears from the late 1990s until now. There’s less of the private, somber, and hidden Detroit. The book explores a more outward domain, toward live music, public festivals, rituals, and meeting places. Was this due to your position as city photographer of Dearborn? And over time, have you seen a change in your approach to photography?

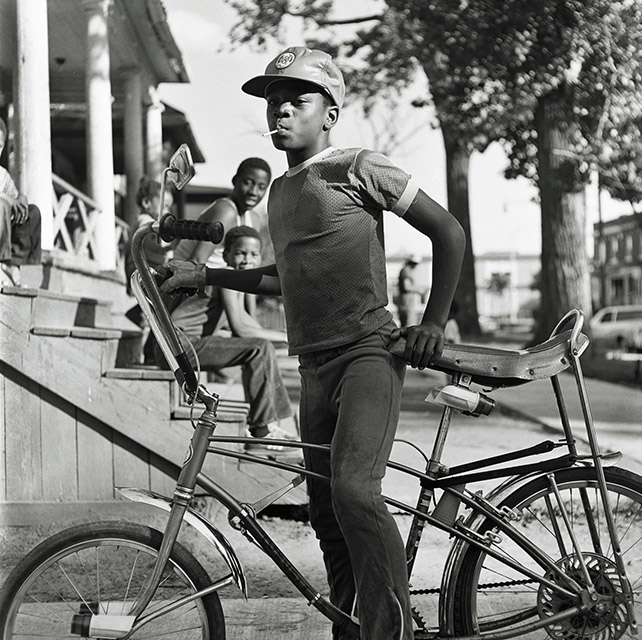

I had a wonderful opportunity to photograph in Detroit when I was a young man. I was on my own and almost without obligation to anyone. I could freely wander the city. I had time on my hands, all the time in the world it seemed then. I loved to explore and find new things in the city and I had a way of meeting and talking to people, and yes, photographing people, that forged a connection with them. I felt free to explore my neighborhood, wherever it might be. I did this from about 1975 to 1986, after which I relocated to Dearborn. Although I continued to visit Detroit (I lived in Dearborn when I photographed for the Urban Interiors project) I could no longer leave my apartment and go for a long walk in the city. I photographed more than human subjects in the early years. Other subject matter of a more formal nature interested me and I took this type of photograph also, even in the city. People photography can be demanding and sometimes stressful, although wonderful and rewarding. In 1990 I became the photographer for the City of Dearborn. It was my job, five days a week, to often photograph people, and not just regular people but often political people. I visited Detroit less and sought other local subject matter like Dearborn’s Zone Coffee Bar. When possible I did some nature photography. Today I do little direct people photography unless they happen to be part of the scene I am photographing. But during the past few years I’ve begun going downtown again, to events as well as just to walk around to photograph things that catch my eye. I loved those wanderings of forty years ago, and find the same pleasure in this today. One of my first assignments at CCS was to cross John R Street and photograph the outdoor David Smith sculpture Gracehoper. I remember I came in close to the large dark planes of steel and simplified and abstracted the forms into a study of line, plane, and texture. I recently returned to the Gracehoper and made many similar images. It feels somehow different now with a digital camera, but the images are essentially the same as that one photo I took back in 1975. So I have come full circle, back to where I began, with a more refined vision. I enjoyed doing this very much and like the results. It is almost like there has been no time in between.

The layout and pacing in the book was well thought out and seemed like a collaborative effort according to Bukowczyk. How do you feel now that it’s published—were you pleased with the outcome?

I am very pleased. I am gratified that after all these years there are a few people who thought my work of some value and worthy of publication. I am another visual voice now added to the other voices who have documented Detroit, each in their own particular way and each focusing on some different aspect of the city. Together we form a quilt that highlights and preserves essential elements of Detroit’s history. I have certainly heard it said that the artist never feels a work is completed. At some point one just has to move on. I could have gone on revising the book. My book offers the kind of image and format that I like. The pictures are interesting, sometimes even pleasurable, but they also can teach the viewer something, A lesson can be found in my book, of which I am not ashamed. I like to think that after looking at and reading my book the viewer may know just a little more than before. I am pleased the way a larger theme runs throughout the background of the book – time moves on, summer turns to winter, there are days of sun and days of rain, all equally beautiful and to be appreciated. One could also say in regards to the photographs of the abandoned rooms at the Niagara Apartments I was doing ruin-porn photography without realizing it. I wish I had photographed more in certain places at certain times, like in the Cass Corridor in the 1970s, especially interiors. I wish I had not lost or discarded many photographs I took during these years. Those are the ones that hurt. Painters, writers, can go back to some extent. Photographers usually can’t. Buildings are demolished, people move away or die, I grow old.

The printing was excellent, but I was a little surprised by your choice in publisher, one not well-known for producing photo books. Why did you decide to go with Ohio University Press and would you recommend them to other photographers?

Ohio University Press proved to be a good choice for publishing our book. OUP boasts an impressive publication list of books of local and regional interest and they are not far from Detroit’s doorstep. OUP was the first press to respond positively to our book proposal and subsequent progress went quickly and efficiently as their professional staff guided us through the process, from finding readers to board approval. Working with the entire staff was a pleasure, beginning with director and graphic designer Beth Pratt. We also had an excellent copyeditor in Tyler Balli. They have published a few other photography books and I would encourage others looking to have their work published to contact Ohio University Press. John Bukowczyk and I are both very pleased with the final result. Sales are brisk, so apparently there are others out there who approve of the book.

At the end of Bukowczyk’s introduction, he writes, “Alas, I no longer think that the good will triumph or that there is an infinite number of sunrises and tomorrows. Bruce still believes.” Do you agree with that statement, and what do you think he meant?

Throughout the years my work has maintained a certain innocence, perhaps even a childlike innocence. For me this is an important part of being an artist. I have shunned as best I could all those peripheral issues that often get entwined with photography – business, art, self-promotion, competition, etc. The photography I do today is in a way very much like the photography I did when I first began using a camera – simple observations and preservation of things I find interesting. Using a camera is fun, it is an instrument of discovery. My optimism about the human race is still strong, perhaps made stronger by all the good people I met while out on my photographic explorations. I have generally found people to be good and have heard many interesting stories of their lives, during the good times as well as times of struggle. I believe it is up to us humans to preserve humanity, there is no other force that will do this for us, we must do it and I believe we are capable of it because of our sometimes latent, but still inherent intelligence and decency. Through the years I have not become jaded or cynical. We cannot afford to be. I think John Bukowczyk recognized this in me, to the extent it is so, and helped me manifest these convictions through my photography. He may have said in his introduction that he no longer believes “good will prevail or that there are an infinite number of sunrises,” but I am not sure I buy this. He has a delightful sense of humor. I have also seen much of the excellent, penetrating, humanistic work he has produced, and continues to produce, and do not feel someone who no longer believes could carry on doing such vital work. Although he may at times try to convince you otherwise, those who really know him, know better.