I arrogantly recommend…by Tom Bowden is a monthly column of small press and books-in-translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired pavement inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page. If unavailable, please call, we’ll try to help. Most of the reviewed titles are stocked at Book Beat. Thank you for your support! Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at:

I arrogantly recommend… by Tom Bowden.

Carte Blanche: The Erosion of Medical Consent

Carte Blanche: The Erosion of Medical Consent

Harriet A. Washington

Columbia Global Reports

Harriet A. Washington is a researcher and reporter of medical malfeasance whose work has received recognition and awards from the National Book Critics Circle Award, the PEN Oakland Award, and the American Library Association Black Caucus Nonfiction Award, and who lectures at Columbia University. The subtitle of Carte Blanche contradicts Washington’s argument; namely, that medical consent was only ever a thing after its violation: So, for instance, while Nazi doctors were rightfully tried at Nuremberg for crimes against humanity by forcing medical experiments upon unwilling participants, lawyers for the doctors’ defense noted that non-consensual medical experiments of the most horrific nature were routinely practiced by the medical establishment of the prosecuting nations—the hypocrisy was as unappreciated as it was falsely self-righteous. So, while “medical consent” is the ethical standard within the U.S., good luck having it granted to you if you are a person of color.

As Washington shows, non-consensual medical experimentation never ended with Tuskegee, and it continues to this day in cities where Black populations are significantly high. In fact, with a population 86% Black, Detroit makes an ideal hub for non-consensual research (housed at Wayne State University), including injections of synthetic blood offering high rates of mortality and harm to various organs and neural pathways. Coercion and refusal to disclose what has already happened are also means of obtaining non-consent, and Blacks in the military (men and women) and prison are also targeted far more than their white counterparts. They are forced to make sacrifices that will most benefit those who least look like them.

Washington documents how these egregious ethical abuses are possible, the legal loopholes that exist created specifically to avoid consent, the for-profit (!) institutional review boards that rubberstamp approvals for coercive practices, and potential solutions to these problems. Carte Blanche is as important as its revelations are awful.

Dancing on the Grave of a Son of a Bitch: The Collected Motorcycle Poems

Dancing on the Grave of a Son of a Bitch: The Collected Motorcycle Poems

Diane Wakoski

Black Sparrow Press

In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, some young women writers began questioning the status quo of their place in society, a society which treated them as less than fully human and their aspirations as trivial indulgences. Of a small representative sample of books from the time, in addition to, say, Margaret Atwood’s The Edible Woman (1969) and Annie Ernaux’s Les Armoires vides (Cleaned Out) (1974) one would add Diane Wakoski’s Dancing (1971, as The Motorcycle Betrayal Poems).

Here is a young woman, early 30s, single and bitter. Bitter at betrayal by men, past lovers—but rather than turn all that anger inward (she turns a fair amount of it toward her face and body) she rages against being treated as disposable, unworthy of commitment. Being first abandoned by her father as a child, “Diane” of the poems seeks approval from men who would have little to do with her. Despite (because of?) her obvious talents and intelligence, she finds herself inexplicably unattached. The uncertainty of the inexplicable leads to fear (self-doubt) and anger (over betrayal of specifically her), examined over the course of this cycle of poems. Back in the day, an impassioned plea for being treated with honesty, truth, and respect passed for “radical politics,” much as it still does today.

From “To Celebrate My Body”:

where

you had only

to touch me

others had

to present a history,

a bibliography,

and a justification

but

no question

remains,

that a gift

easily given

lightly received

is wasted

no one can

touch me

the way

you can / I should say

did

but

no question

remains

your touch

was not lightly

taken

and my body

has spent

a lot of years

awakening

(Full disclosure: Wakoski in the late ‘80s, early ‘90s served on my dissertation committee in the English Department at Michigan State University. I never wrote the dissertation, so she and I only ever had chatty conversations.)

Hers

Hers

Maria Laina / Karen van Dyck

World Poetry Books

Karen van Dyck has rendered Maria Laina’s Greek into still, meditative moments reflecting the self-confidence of a woman on the early end of middle age. (Laina, born in 1947, published Hers (in Greek) in 1985.) None of the poems are titled, but here’s one that hints at the book’s mood:

She drinks a cup of coffee

and gets pleasure

from lighting a cigarette.

She will not grow old calmly.

Most poems are brief—none over a page—and epigrammatic, evoking moods and scenes easily imagined as film clips. Here’s one on the palpable erotics of self-assurance:

As she grows older

she departs with greater ease.

Perhaps even allure.

As alluring to others as self-confidence may be, the allure does not also signal need. She remains erotically self-sufficient:

She has nothing to say.

She simply touches herself

and watches herself

and wants

Laina expresses one woman’s autonomy in gentle, understated terms and rhythms that van Dyck conveys exquisitely.

Ghazals

Ghazals

Mir Taqi Mir (Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, trans.)

Murty Classical Library of India / Harvard University Press

Mir Taqi Mir was an Urdu poet born in Agra, India whose poems were based on the Persian ghazal tradition. Living from 1723 to 1810, Mir was thus roughly a contemporary of William Blake, Byron, and Coleridge. Ghazals are a poetic form of five to 15 rhyming couplets (rhyming in Urdu, that is) that typically deal with melancholy aspects of love. As with Shakespeare’s sonnets, most of Mir’s ghazals are clearly directed toward a woman, while some are directed at males, underage boys. With Mir, poor boys serve as a physical counterpart to the idealized female epitome.

Here is ghazal 97 in its entirety:

Yesterday some friends took me into a flower garden.

I didn’t find fragrance similar to hers in the rose or in the jasmine.

The sweet tongue of the beloved slays me.

How I wish that tongue were in my mouth.

Like a whirlpool I went round and round in this ocean.

My life in my native land was spent in vertiginous wandering.

If I went to my grave with this charred and smoldering heart of mine

a blazing fire would consume my shroud.

You’re what makes me live, but oh, your tight-fitting dress is a cruelty.

I can see that your body has the soft and delicate style of the soul.

I fear it might cause your body to go numb—you are much too delicate—

this close-fitting dress of yours that clings so tightly to your body.

Mir, it would be a catastrophe if she looked me full in the face—

she who turned a world upside down with just a wink of her eye.

After being rejected once again by his female beloved, Mir seeks out boys for physical release. However, this practice seems to be an eccentricity of Mir’s rather than an accepted cultural solution to a romantic impasse, since he reports being socially rejected for seeking out boys. “What deadly grievous sin did I commit in giving my heart away to the boys? / Why is everyone in the city, young or old, gossiping about it?” (Ghazal 112). (As the late translator Shamsur Rahman Faruqi notes in his introduction, sexual ambiguity also extended to ghazal conventions, too, since—for a couple of centuries—the beloved was addressed as male rather than female.)

Faruqi’s notes and introduction to Mir and his poetry are excellent for providing background and clarifying some of the subtler nuances of Mir’s allusions and Indian poetic practices.

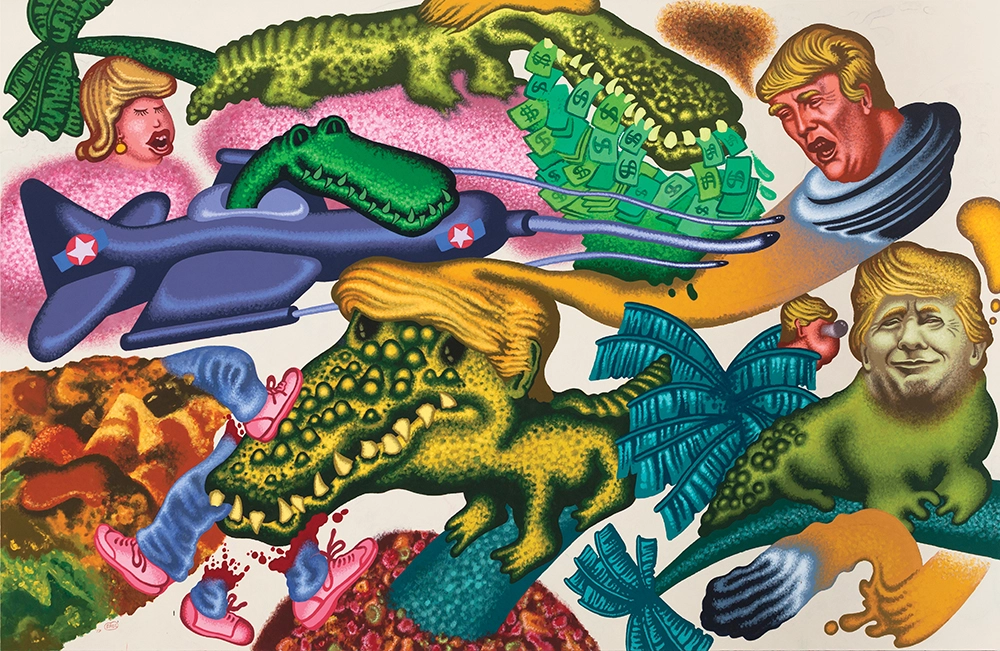

Peter Saul: Professional Artist Correspondence, 1945-1976

Peter Saul: Professional Artist Correspondence, 1945-1976

Dan Nadel, editor

Bad Dimension Press

Peter Saul is as an artist during whose early career almost thumbed his nose at the idea of Pop Art (which he was at first associated with): instead of mechanically reproduced paintings in homage to mechanically reproduced objects, à la Warhol’s soup cans (but before Warhol came along), Saul made teen-like cartoon doodles, some of them (like “Custer’s Last Stand #1” and “Washington Crossing Delaware”) show an affinity with Basil Wolverton’s Mad magazine-era drawings, while others (like “Untitled (Blue Interior)” and “Master Room: Hide Away” of 1960 and 1961) share affinities with Basquiat’s painterly tics (which came much, much later). And, unlike the icy surfaces of Warhol paintings, Saul’s pictures never made his audiences wonder what to make of them.

Peter Saul, the book, provides a look back at the artist’s life from age 10 to age 41, based on the letters he wrote, largely to his parents, at first, then his art dealer, Allan Frumkin. The topics include his assessments of the art world’s collectors, museums, and viewing publics; and his assessments of the qualities that make a painting great—mainly, interesting ideas and the technical chops to best portray them. As with his subjects’ compositions, Saul’s book’s subtitle is both ironic and a poke at academic values (so-called professionalism). In 1945, when this book begins, Saul was 10 years old and at boarding school. As an artist, he had two pieces of good fortune: his parents had the means to support his aspirations, and early success in the form of showing and selling internationally by age 28.

There is less art world gossip than explanations of his intentions, verbal descriptions of his paintings, which work of contemporary artists he liked (S. Clay Wilson’s cartoons (!)) and disliked (found Frank Stella’s constructions shallow), and the casualness with which exhibits are arranged. With his exhibition history beginning in Europe then expanding across the U.S. (NY, Chi, LA), he brings to his aesthetic assessments first-hand international experiences in trends, movements, and preferences among the viewing public, collectors, and museums. His paintings’ themes included Vietnam, racism, hypocrisy, sexual exploitation, and avarice.

These themes put off some viewers, while his neon-colored, surrealistic cartoon style led some reviewers to assume he wasn’t serious.

While praising his own art for its offensiveness and bad taste, he also reports being able to sell every painting and drawing he makes, often having difficulty keeping up with demand, despite the bad reviews. And just who were these collectors of offensively lurid images? For Saul, the best of them numbered about 50,000 across the world, only they who had the taste and sensibility see the craftsmanship behind the crass—those whose opinions mattered to him. But by age 40, around the time this book ends, he is telling his art dealer that he’s tired of being offensive and wants more people to like his work so he can be a success. Perhaps Saul might appreciate these lines from The Clash’s song, “Death or Glory”:

I believe in this

—and it’s been tested by research—

that he who fucks nuns

will later join the church.

Homeward from Heaven

Homeward from Heaven

Boris Poplavsky / Bryan Karetnyk

The Russian Library at Columbia University Press

Written and set in Montparnasse between the wars when Boris Poplavsky was one of many expats who fled Russia after the October Revolution, Homeward from Heaven concerns the eccentric spiritual growth of Oleg, a young man of about 29 years of age when the book begins, who freeloads / hobnobs with the scions of wealthy Russian expats. Taking place from 1932-1934, and written soon after, the book is startlingly sexually explicit in describing its characters’ fantasies and exploits, be it alone or coupled. It’s a young man’s novel—filled with boundless physical momentum and the shrillness of strong opinions stated with inflexible assuredness—only to be contradicted the next day with equal inflexibility. Thus, Oleg also makes for a frustrating protagonist for readers to engage with—which is not necessarily a bad thing, since cultivating empathy for others rather than understanding them is one of art’s goals.

Oleg hangs out with a group of young Russians enjoying sex with each other and breaking hearts over indecisions regarding who will be whose fuck buddy. Oleg’s acceptance into the group is ambivalent: Despite having such assets as extroversion, physical fitness and agility, and rugged good looks Oleg is naïve, foolish about and frightened by sex, and socially inept, talking boorishly at length when drunk.

Naïve idealist Oleg is initiated into a belated frustrated-summer-of-love ritual by falling head-over-heels for the wealthy and jaded Tania, an icy-hot young woman who lacks the empathy to tell him she does not return his feelings but continues to flirt with him. He writhes in frustrated sexual agony, incapable of believing his pure angel capable of lewd desires.

According to the introduction by Bryan Karetnyk, the novel’s excellent translator, Poplavsky’s friends saw Oleg as the author’s semi-autobiographical stand-in, which accounts for the novel’s unplotted drive toward spiritual enlightenment. Despite his emotional and psychological intensity, Oleg’s drive toward betterment is undisciplined: Although he spends hours reading in the library many days a week, he dropped out of college first semester, he leaves jobs within hours of starting them, and he changes from intellectual enthusiasm to enthusiasm almost daily, so that he never accumulates knowledge, except bodily. (Apparently, Poplavsky’s behavior wavered oddly, too.)

After recovering from the lover-who-wasn’t over the next nine months, come the next summer, Oleg discovers the charms of Katia, to whom—after much confusion on Oleg’s part lasting months—he loses his virginity. And then returns to Tania. But before Oleg begins freely spreading his seed, we’re told that his disciplined mind and body prohibits masturbation, so that when he does ejaculate, Tania and Katia suddenly look like Santa Claus. . . Well, no, not quite. But at this point the novel’s spiritual dithering gives way to macho sexual imagery. For instance, in addition to learning that Oleg doesn’t wear underwear yet is apprehensive about dribbling pee-stains on his pants, we are also told that his penis is unwashed and unclean of smegma, and that its length may be used to infer the relative heights of each woman: Since for Katia Oleg’s penis extends from her vagina to just below the heart, but for Tania it extents to just the midriff, Tania must therefore be taller than Katia. Either way, Oleg finds momentary solace in gymnastic sex.

But, in keeping with his irresolute nature, ultimately Oleg decides to dispense with Tania, Katia, and the erotic life in general; chooses to renounce work (first item on his list, pre-checked); take up asceticism; and strive toward some spiritual betterment after the debauchery. It’s hard to take him seriously. And yet, at the novel’s end, when Oleg lights out for the territory to focus on furthering his spiritual growth, a reader can only take him at his word, as delusional as it might be. Perhaps his outcome would be better than Poplavsky’s, who overdosed on heroin before this book could be published.

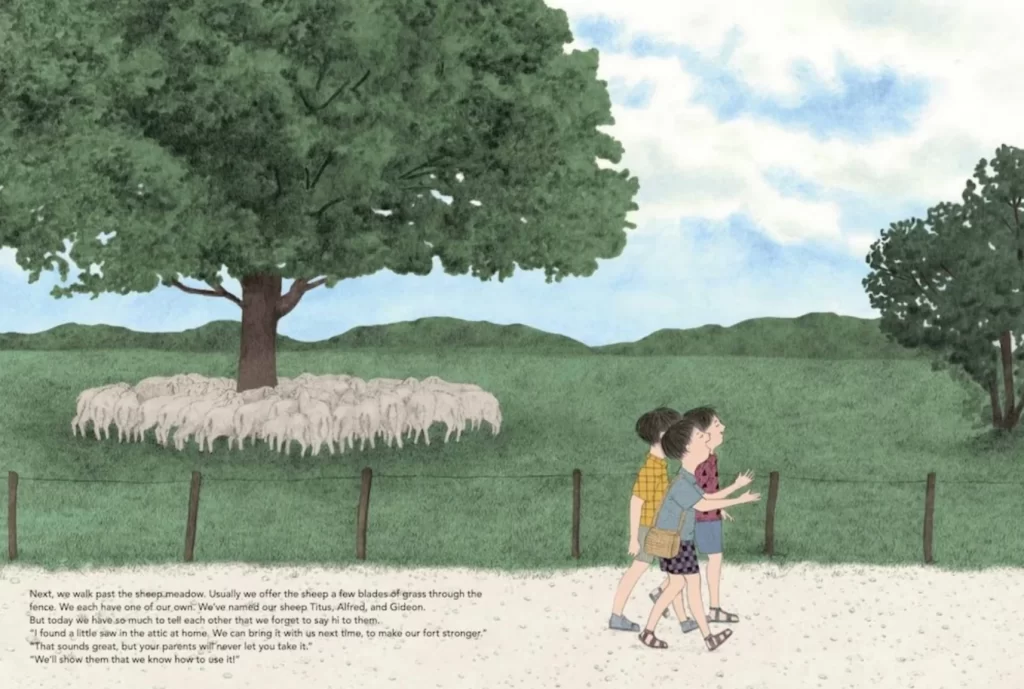

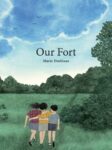

Our Fort

Our Fort

Marie Dorléans / Alyson Waters

NYRB Children’s Collection

An excellent book for children ages 4-8 about a trio of siblings, friends—the relationships aren’t clear and seem irrelevant to the book’s greater concern of conveying the camaraderie among young people who share the same experiences and goals. In this case, the goal is their fort, and the experiences are what they see and do on their walk there. The setting is a bucolic paradise waiting to be explored and experienced by kids. Living in the country, to reach their fort the children must traverse dirt roads and deep grassy fields—and endure an unexpected (but foreshadowed) gale-force wind that lasts several scary minutes.

The book’s author and illustrator, Marie Dorléans, is a young artist who graduated in 2010 from the School of Decorative Arts in Strasbourg, France, and whose last book, Night Walk, won the Prix Landerneau for best children’s book. Her illustrations for Our Fort couple fine lines with broad swaths of color for the trees, sky, and grasses. Having a trio of pals to illustrate allows her to balance the two-page spreads with different configurations of their placement and the subject of the illustration: a solid eye for design that looks natural not contrived. Alyson Waters’ translation is rendered into natural-sounding, idiomatic English as it is spoken by adults, thus avoiding the trap of assuming books about and for children need to sound like children to be understood.

What about the fort? Well, that’s the whole point of the story. Read the book to find out.