Small Takes focuses on 10 titles 150 pages long or less, including books, chapbooks, magazines, zines, journals, enchiridions, and other bound ephemera. Links at each review take readers either to Book Beat’s affiliate page on Bookshop.org or directly to the publisher.

Tom Bowden’s column “i arrogantly recommend…” often appears monthly in the Book Beat newsletter.

Jacobé & Fineta

Jacobé & Fineta

Joaquim Ruyra (Alan Yates, trans.)

Fum d’Estampa Press

Fum d’Estampa is an indie press new to me, out of England, focusing on translations of Catalan literature. Jacobé & Fineta is a book of two stories by Catalan writer Joaquim Ruyra (1858-1939), “Jacobé” a recollection of the narrator’s nanny and her death, and “Fineta” about the trauma of rape. I don’t read Catalan and so cannot compare Alan Yates’s translations against the originals. However, even if the stories were originally written in English, I don’t see how the prose could be improved upon. Here is an excerpt from the opening paragraph, which sets the tone of the story and where it occurs:

Autumn is here, that time of the year when leaves are falling and invalids become sad from feeling in their hearts that some life force is fading there, too, inside them. The wind in the trees seems to be murmuring words whose ominous meaning can be vaguely deduced from the sadness of the intonation and from the sallow hue they produce in the plant life everywhere. . . Nature is complaining as it goes into decline. And I have the strong feeling that it is not the cold which creates this sense of things coming to an end: . . . it is something death-like which moves through the land in accordance with an annual rhythm, of the same kind that occasionally stretches a fine veil of drowsiness over our eyes.

Manguet, the narrator of “Jacobé,” tells the story of his nanny, a girl only two years his elder whose required services decline as the narrator ages and Jacobé herself is needed more around the house. Nonetheless, Jacobé and her mother remain as fond as Manguet as he them, even when he goes off to college. On Manguet’s returns to his hometown, he finds Jacobé transformed by madness (depression, schizophrenia, something else?), which wastes her to skin and bones and often finds her hallucinating. Her end, witnessed by Manguet, is as pathetic as it is inevitable.

“Fineta” is about the near rape of the eponymous character and its consequences. The 16-year-old daughter of a fisherman, Fineta awaits the return of her father and brothers from an overnight fishing expedition, waking up early to go to the beach, encountering on her way a vagrant the neighbors call the Woodman, a man with “matted ginger hair, as spiky and hard to the touch as those on a coconut shell,” and whose “lumpy wide face,” “receding chin and those thick lips disclose a strange personality disorder.” Insane or retarded, he is untrusted by the locals, and his tracking of Fineta to the beach while she plays in the water almost results in a horrible physical outcome. The mental outcome, the after-effects of the encounter on Fineta, suggest a trauma that may not heal with time.

A short and punchy book that left me wanting more by Ruyra to read.

Transparent Body & Other Poems

Transparent Body & Other Poems

Max Blecher (Christina Tudor-Scott, trans.)

Sublunary Editions

Max Blecher (1909-1938) was a Romanian writer whose brief career was bracketed by a diagnosis of spinal tuberculosis, which largely invalided him the last 10 years of his life. In addition to several novels, he also wrote some poetry, the entirety of which (20) are collected here and translated into English for the first time with facing originals in Romanian.

Given Blecher’s diagnosis and the number of years he suffered, little surprise should be taken in the poems’ bittersweet tone and more in their ability to convey composure as well as they do. Here is the entirety of “Your Hands”:

Your hands on the piano like two horses

With hooves of marble

Your hands on the vertebrae like two horses

With hooves of roses

Your hands in the blue like two birds

With wings of silk

Your hands on my head

Like two stones on one grave.

Comfort, its opposite, and their balance are issues that run throughout these poems, like the closing couplet from “Love, Moth of Black Ports”:

Love, meshwork of a world in which the trapped

Dance like reflective and insane clowns.

A nice observation, that clowns (people) come in two flavors—reflective and insane—but at the end of the day, one is still a clown. Even in pain, Blecher doesn’t take himself too seriously. Christina Tudor-Scott’s translation is excellent. Recommended.

Second Factory #3

Second Factory #3

Ugly Duckling Presse

A fairly new publication out of Brooklyn (see my review of issue #1 [https://www.thebookbeat.com/backroom/2020/08/02/i-arrogantly-recommend-by-tom-bowden-5/]), chapbook-sized (40 pages), with at least one page devoted to the poetry (mainly) or art of each contributor. Issue #3 features work from 20 contributors, young and emerging artists. Lines from two poets make me glad I’m retired. For instance, from Patty Nash’s “Scrum Dulcet”:

I wept for the hours

I spent in a webinar

At “work,” apostrophes

Ironizing my time

In a quasi-oval

And this from Ariel Yelen’s “New Year Poem with Green Flooding”:

I don’t want the job

Of hating my job

Chris Reynolds’s typewriter poems use keys like small, stylized brush strokes, overlaying different marks, using red ribbon as well as black, and so forth to create abstract pictures; and Bianca Messinger contributes five poems that elicit the moody pop-ambience of Joanna Brouk’s music.

Beginning with Issue #4, Second Factory will start publishing work by contributors beyond Brooklyn’s borders. Interested poets and artists should both check out an issue and check out the magazine’s guidelines. The window has already closed for submitting to Issue #4. But keep an eye out on their social media for future announcements.

Epoxy #6

Epoxy #6

John Pham

John Pham’s self-published Risographed comic book series Epoxy (“in lush soy ink in my garage”) features the exploits of a couple named J and K (whose earlier exploits are collected in J & K published by Fantagraphics last year). Epoxy #6 includes a hand-painted film cel; an episode from Pham’s science-fiction story, “Deep Space,” about the remaining crew of a crashed spaceship; an autobiographical four-page insert and, a 5”x6” zine insert featuring a new J and K story, in which the couple, exhausted as new parents to their baby, Bacne, find an old woman named Babushka to babysit him. While the parents play, Babushka takes Bacne on a shopping trip of sorts for ingredients for the pierogies she sells, including dumpster diving—it’s every parent’s (benign) nightmare. But Bacne is happy, so the parents are happy. Beautiful Risograph work throughout, and the different stories demonstrate the different styles Pham has cultivated.

I Have Seen the Bluest Blue

I Have Seen the Bluest Blue

Natalee Cruz

Ugly Duckling Presse

Natalee Cruz’s first chapbook of poetry, I Have Seen the Bluest Blue, focuses on the deportation of her stepmother to Mexico and its aftermath for the couple. The book has two parts, petitions to the court on behalf of her father, Pedro, for allowing his wife to re-enter the U.S. and the court testimony his wife was never asked to give.

Each part of the book takes a “repetition with variations” approach to telling the story, but I was more emotionally engaged by the form adapted in the book’s first part than in the second. In the first part, the poet’s “letters of support” for her father’s plea are presented as variations on a structure that sounds extracted from questionnaires: who are you supporting, how long have you known this person, in what capacity, etc. Cruz then plays with this structure so that in addition to words and phrases changing from plea to plea, the subjects and objects change and disappear, too. What emerges is a 3D person, whose case is pled for at varying levels of ambiguity regarding Pedro’s health, all emotionally charged with empathy. (Two words never change: “husband” and “friend.”)

The form of the second part, Gudelina’s tale of the separation, is closer to the work of erasure: A starting text is edited—words scratched out or erased—to find new statements within the original. In this case, as the poems go on, more and more of the original is erased, until the last poem, which ends with demand for better treatment for all people in Pedro and Gudelina’s position.

I Have Seen the Bluest Blue is an excellent first chapbook. The narrative is confident and assured throughout the first part, but in the last two poems of the second part an impatience arises in the tone, so that, while the anger behind it is earned, the ending feels forced and rushed. Nonetheless, an impressive and recommended debut.

The Man Who Planted Trees

The Man Who Planted Trees

Jean Giono, with wood engravings by Michael McCurdy

Shambala

“There are times in life when a person has to rush off in pursuit of hopefulness.”

—Jean Giono

The Man Who Planted Trees is a short story originally published in 1954 by Vogue and republished in this volume—about the size of six postage stamps arranged 2×3—which has been in print since 1985, and illustrated by Michael McCurdy, whose woodcuts are lushly yet distinctly detailed, even in this tiny format. The second part of the book is an essay on Giono by Norma L. Goodrich, who recounts her meeting with Giono in 1970, the last year of Giono’s life.

“The Man Who Planted Trees” concerns a sort of French Provençal Johnny Appleseed, although the man in this story, Elzéard Bouffier, remains in one house and spends his days walking kilometer after kilometer, planting tree seeds on the sparse plain along the way. The man lives alone, a widower with a dead child, and silently does his work, one type of tree at a time, each “time” lasting perhaps several years. Bouffier does the math—of 10,000 planted how many will survive? how many will last?—and antes his time. The story is an allegory of perseverance, of how simple acts that seem like harmless, meaningless hobbies accumulate significance over time and show what the meekest among us can accomplish with persistence.

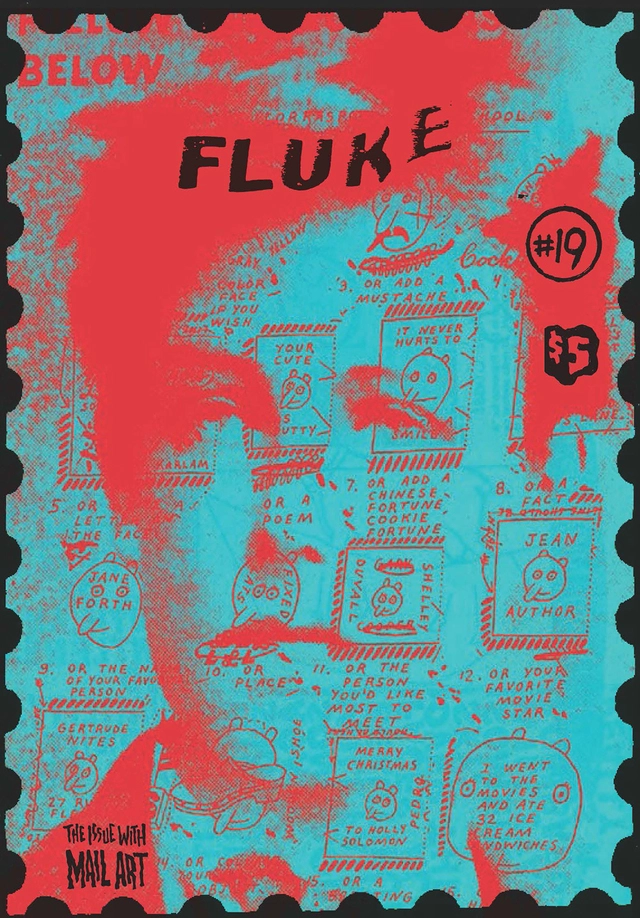

Begun three decades ago as a zine devoted to punk-culture and DIY ethos, this 30th-anniversary issue focuses on the DIY side of art as embraced, created, and cultivated by the Mail Art movement. In addition to full-color photos of examples, editor Matthew Thompson provides interviews with key figures in Mail Art, including one previously unpublished with Roy Johnson from 1977:

Johnson is credited as the founding figure of (U.S.) Mail Art. Other figures interviewed include such key figures as buZ blurr, Anna Banana, Leslie Caldera, John Held, Jr., and others from Sweden and Japan who have been creating, curating exhibitions, and collecting Mail Art for decades. The enthusiasm is palpable.

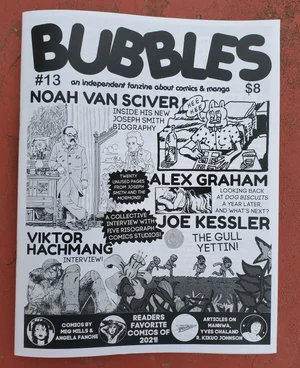

Just before the pandemic set in, comics enthusiast Brian Bayles started “an independent fanzine about comics & manga,” 56 pages, 8-1/2”x11”, in the breath-taking black-and-white tones we’ve come to expect from photocopiers. Three years and 13 issues later Bubbles has gathered an enthusiastic, contributing readership who eat up the zine’s (Bayles’s) interviews with and profiles of top practitioners in the field today, and that often include extra material unavailable elsewhere. Like, say, Fantagraphics’ Comics Journal, Bubbles takes in a broad range of comics and manga, minus the already over-publicized superhero titles, and its editor and contributors are pure comics nerds who have done their homework.

Issue #13 includes an interview with Noah van Sciver (author of Fante Bukowski) and a 20-page insert of deleted material from his upcoming graphic history, Joseph Smith and the Mormons, two dozen or so reviews of new books and zines, a feature on Risograph printing, and—of course—lots more. Bayles now has enough interest in the zine to offer subscriptions to it (recommended), three issues a year. I always come away from each issue with a new list of titles to track down and artists to look up.

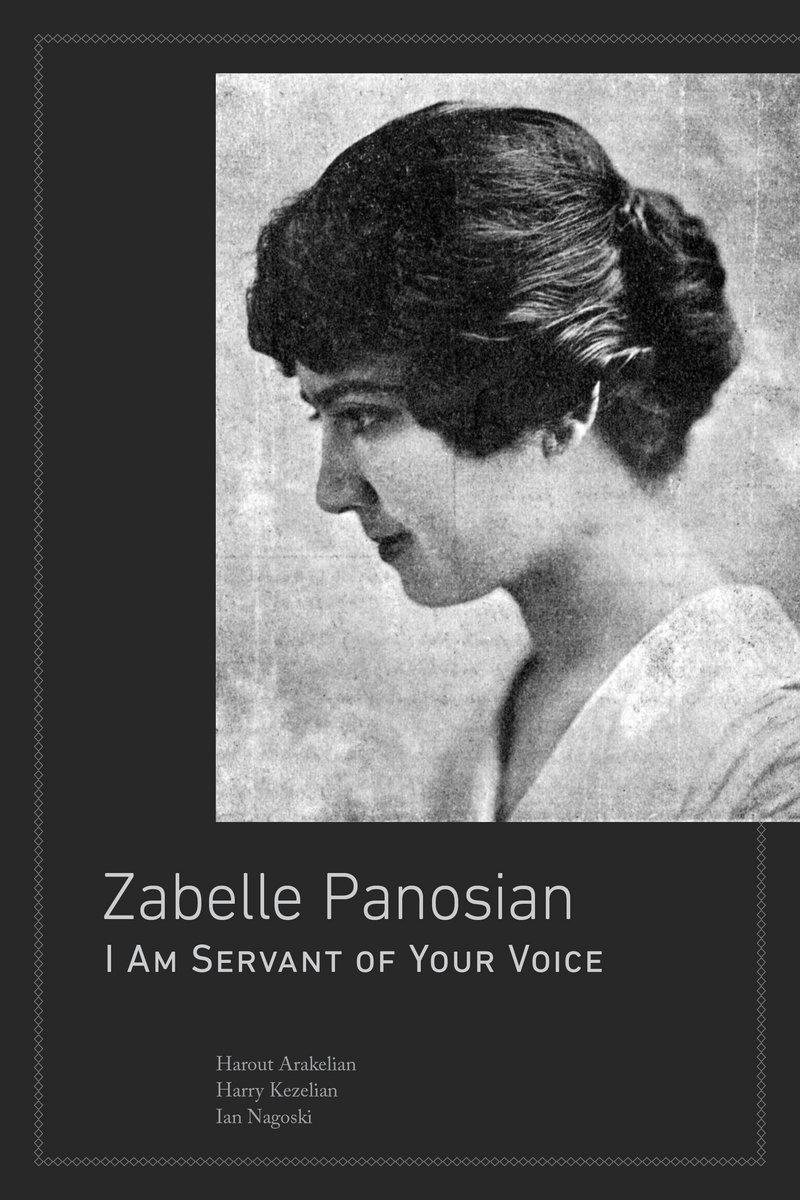

Zabelle Panosian: I Am a Servant of Your Voice

Zabelle Panosian: I Am a Servant of Your Voice

Harout Arakelian, Harry Kezelian, Ian Nagoski

Canary Books & Records

For 20-some years now, self-taught musicologist Ian Nagoski has sought out, sonically, spiffed up, and reissued on Bandcamp music by European immigrants to the U.S. in the first decades of the 20th century, adding his own liner notes about the performers and performances based on his diligent research into areas with little surviving documentation. Zabelle Panosian: I Am a Servant of Your Voice is a biographical liner note writ large, with a CD of Panosian’s recordings included. Harout Arakelian and Harry Kezelian are credited here for their research expertise, findings, and ability to read and translate Armenian.

Takouhi (aka Zabelle) Der Mesrobian was an Armenian émigré to Boston who married young (15) and fortunately. Her husband, Aram Panosian, 10-15 years her senior, was part of a young, industrious, and prosperous set of Armenian Americans, making his fortune printing postcards. Unusual for the time, Zabelle’s husband supported her desire to sing and paid for her vocal lessons. Within a few years, she was locally popular and played a role in several significant charity events for victims of Turkey’s genocide of Armenian Turks, including several fund-raisers in Detroit. She recorded only a dozen or so songs (plus multiple takes) before withdrawing from recordings. Her voice is clear, with a light tremolo, and what I think of as a “flat” timbre. She wasn’t a belter, and her singing has a fragile tone to it.

The end of her recording period was not the end of her career, and the recordings she left behind were made before her voice reached its peak, about ten years later. She began with a promising but untrained voice and eventually incorporated technically difficult arias into her repertoire, which received high praise in the press. Early in her career she was often paired in a supporting role with an older tenor and co-Armenian, Armenag Shah-Mouradian. By the time of their pairing, Shah-Mouradian was already well-established and popular. Ten years later, he was the supporting act.

She toured Europe and the Near East for four years, bringing her 11-year-old daughter, Adrina, with her. Adrina would later become an entertainer in her own right. Further vocal lessons in Paris helped Panosian’s talents emerge further, so that when she and her daughter returned to Boston four years later, her voice was so improved that she re-emerged on stage as Zabelle Aram, replacing her husband’s surname with his given name. Those who remembered her performances of five years before were wowed by how well her talents had grown.

Her career peaked by age 37, around the time Adrina took to the stage as a “Spanish” dancer. While Zabelle gave few documented performances after her highpoint, her life remained entwined with her daughter’s. Arakelian, Kezelian, and Nagoski provide a parallel biography, too, of Adrina’s life as a dancer, rich in its own right, but the paper trail ends about 25 years before their death.

Tender

Tender

Ariana Harwicz (Annie McDermott & Carolina Orloff, trans.)

Charco Press

William Faulkner goes to Argentina in Tender, a short novel about an alcoholic mother and her 16-year-old son, showing that neither is quite the adult in the relationship. In addition to the mother’s incestuous fondness for her son (the attraction is mutual), she’s usually passed out when not stand-up drunk, or behind the wheel of her car for drives frequently ending in fines and fender-benders. She’s a frequent hospital visitor, given one scrape or another, and prone to seizures, given one head injury too many. Social workers and school officials worry about her scrawny son, the subject of teasing ridicule on those days he does show up to class. She spends the entirety of her savings on buying him a moped, which he promptly races and crashes, and the police impound it. On her idea of principles, she refuses to the pay the ticket that would allow them to have the moped back, one of the few sensible decisions she makes in that it prevents mother and son from further mischief in that form. Their lives, as Alfred Toynbee noted of history, are just one damn thing after another.