The Disappearance of Jim Sullivan

The Disappearance of Jim Sullivan

Tanguy Viel (Clayton McKee, trans.)

Dalkey Archive

Finally: An international novel that takes place in Detroit! Sort of. The Disappearance of Jim Sullivan is a novel by a French author about a French author who is tired of writing French novels and instead wants to write the kind of novel he sees everywhere, in airports and bookstores around the world: an “international novel,” written by the same set of authors, all of whom are American.

Thus, the international novel is necessarily an American novel. More so, the narrator thinks, an American novel must be set in a mid-western town, which in this case is Detroit. Furthermore, since the narrator is following what he sees as a successful formula, he decides that his protagonist, Dwayne Koster, should be middle aged, recently divorced, and possessed of a drinking problem. The novel’s “Detroit” is also reductionist, sounding like factoids about the city and its suburbs cobbled together from the first 20 results of a cursory Google search—which is to say that, while the individual facts deployed may be true, in the aggregate they form a portrait no Michigander, let alone Detroiter, would recognize, or at least would see as anything other than a shallow caricature. This is part of the novel’s charm: it’s clunky deployment of authenticity signaling.

For instance, when the narrator is introducing the backstory to a character named Susan Fraser, Dwayne Koster’s future, then ex-, wife, he writes: “She was the kind of girl that you could imagine in a Renaissance Center office, managing the sales department of an automobile firm, as easily as you could picture her at a punk concert at the Masonic Temple, especially a punk concert at the Masonic Temple.”

I was born too late to be a part of the punk movement but one of the first things I thought to myself was that it would be good for a character to have been a punk while growing up in Detroit, maybe even to have fallen in love at an Iggy Pop concert. Then a little later, having matured over the years, the character would honeymoon at Niagara Falls. That’s exactly what happened to Susan Fraser. The first time she kissed Dwane Koster was the day of the legendary Iggy Pop concert at the Masonic Temple on March 23, 1977, without knowing that she was going to become his wife, let alone the mother of his children, or that they’d spend their honeymoon in the mist of the Falls, or that twenty years later she’d regret it.

At any rate, the narrator describes to us the contents of his “American” novel as well as the reasons for his various editorial decisions in having his characters behave as they do. I won’t repeat the plot here, which indeed does have a so-called action novel structure to it with illegal international shenanigans, but in Tanguy Viel’s hands, the plot is secondary to Dwayne’s foibles, which, true to classical tragedic form, lead inevitably to his final act.

Rather than a parody of genre writing—which it is, in part—Viel’s The Disappearance of Jim Sullivan demonstrates by inverse example that the conventions of genre—its plotlines and character types—are not the elements that make a story bad or good but that how a story is told determines whether it is liked or disliked, found comic or tragic, etc. Who’s Jim Sullivan? That you can Google, and maybe stream his songs.

Potsdamer Platz; or, The Nights of the New Messiah—Ecstatic Visions

Potsdamer Platz; or, The Nights of the New Messiah—Ecstatic Visions

Curt Corrinth (W. C. Bamberger, trans.)

Wakefield Press

Categorized as an expressionist novel—a short-lived sub-genre of the early 20th century—Potsdamer Platz’s so-called “new messiah,” mild-mannered Hans Termaden, could be seen as a country rube, who, upon arriving in Berlin, becomes overstimulated by the city’s hubbub and bright lights, and thus (?!) desperately horny. He meets a young woman whose willingness to strike up a conversation with him he mistakes for sexual charisma, an assumption she disabuses him of by demanding money before sex. Despite telling him that “people need to get by,” he doesn’t understand why somebody would charge him for sex. Nonetheless, the act’s results upon Hans’s emotional state transforms her into, in his eyes, the Red Queen.

So addled by sex with the Red Queen, Hans decides, first, that his mission in life is to find women who would enjoy idolizing and having sex with him. Then, second, he decides that other men might benefit from a good orgasm, too, and so he wanders Berlin’s streets, pulling aside lonely men, promising to pay them to have sex with the Red Queen. He becomes, essentially, a philanthropic pimp, hiring women he pays to have sex with whoever shows up. Women who wish to volunteer their services are, of course, welcome, as the entire purpose of the enterprise is to have as many people as possible fuck as much as possible. Hans’s unstated assumption seems to be that, after initially underwriting the enterprise of sex, the vast majority of—if not all—people will insist on compulsive sex as a matter of principle: Exchange of bodily fluids, yes; cash, not so much.

As world capitols are depopulated by citizens fleeing to engage in orgies in Berlin, male homosexuals, of all people, are angered by this hetero behavior (even though the Messiah’s sexual revolution says nothing against homosexuality) and band together as the (unfortunately named) “black Uranians,” attacking heterosexual orgyists in a fit of jealousy (!). Outnumbered, the gays retreat but promise revenge, briefly uniting forces with the Prussian Army (also !). But upon encountering a platoon of horny women, the Prussian army drop their guns and pants. Foes defeated, nonstop world orgasm achieved, the Messiah ascends to Heaven. (Spoiler alert.)

An exercise in ardent, flamboyant kitsch that is quickly paced and imaginatively thorough. (The sex scenes not so much. In that way, the book is perversely modest. The reader is assured, however, that the mated couples have each achieved, in private, magnificent levels of orgasm.)

Cold Enough for Snow

Cold Enough for Snow

Jessica Au

New Directions

Cold Enough for Snow is told by a middle-aged woman who coaxes her mother to vacation with her in Tokyo for a few weeks. The narrative purpose of the trip is to provide moments of reverie and association for the narrator regarding her relationship with her mother, with her sister, and boyfriend, and what she wants from life, while the mother and daughter visit museums and eat in restaurants. The cultural expectations (Southeast Asian) seem to be low for women to actually find enjoyment and meaning in their marriages, let alone seek it out: The point is to be in a relationship, or be an outsider.

The narrator comes to see that her mother, like herself, is isolated from others, but for different reasons. (The mother, from Cantonese-speaking Hong Kong, settled as an adult in Australia, where the daughter was born, fluent only in English.) Recollecting conversations with her boyfriend’s father, a sculptor, she realizes that she is happiest when in the presence of beauty, but the personal path to living a life in that state as a goal requires the strength to refuse compromise. Her mother’s life and temperament may help her determine her next life choices.

Time among the Sphinxes

Time among the Sphinxes

Christian Bök

Penteract Press / Eneract Editions

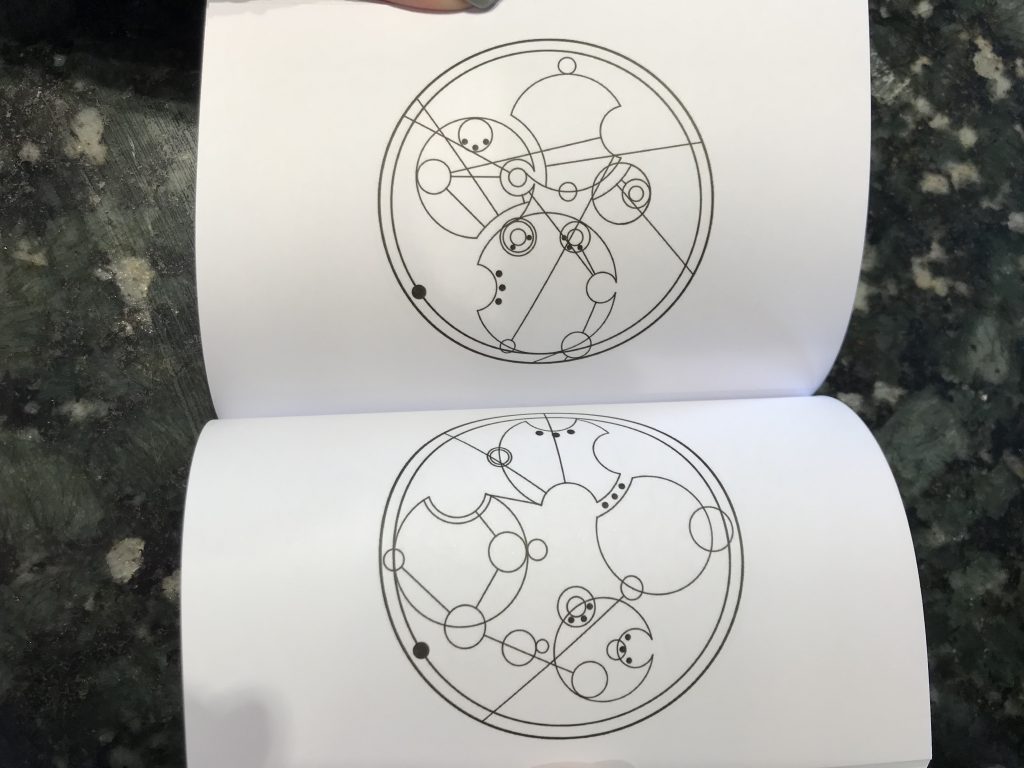

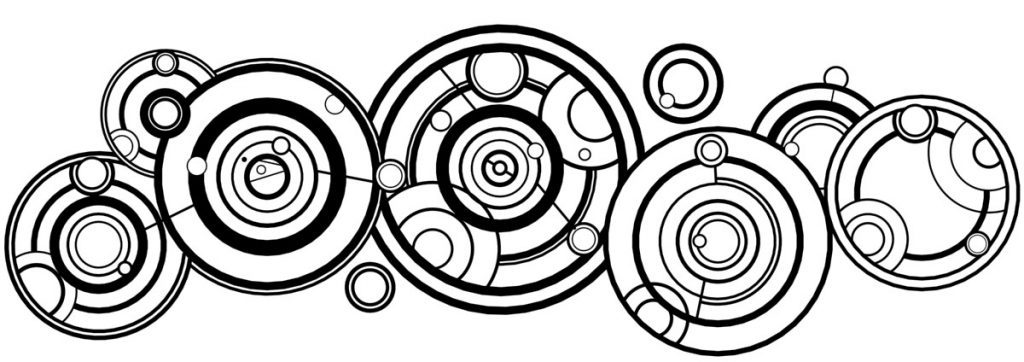

A short and beautiful new work by Christian Bök, whose Euonia I first encountered 25 years ago, and which still makes me laugh every time I read passages from it. Bök works within constraints, much in the Oulipo mode, and in recent years has blended visual representation among the constraints, so that art and text merge. In the first half of book, “Translating Translating Apollinaire (Gallifreyan),” Bök translates bpNichols’s English translation and transformation of lines from Apollinaire’s French poem “Zone” into Gallifreyan, a language from “Dr Who,” the alphabet for which was originally devised by Loren Sherman. (Nichols’s Translating Translating Apollinaire may be downloaded here: http://www.bpnichol.ca/sites/default/files/archives/document/Translating%20Translating.pdf; Gallifreyan letters and instructions on writing may be downloaded here: https://shermansplanet.com/gallifreyan/guide.pdf.)

What’s the point? For me, a few things: (a) I’ve always been attracted to alphabet symbols that are beautiful to look at in their own right, whatever they’re saying—the various languages of South East Asia are good examples; (b) good writing usually reads well aloud—might a well-written sentence’s or paragraph’s words be as visually appealing as they are to hear?; (c) now that I see an alternative alphabet and have instructions on how to decode it, who says sentences must be written only straight down or across, and what is gained or lost by doing so?

The second half, “Time among the Sphinxes,” is Bök’s manifesto about avant-garde artists and the role they have in shaping and telling us about the future, often by wrestling with the past.

Highly recommended.

Stupid Baby

New Juche

Amphetamine Sulphate

The thirty-something narrator of Stupid Baby, a Scottish ex-pat, lives in a Thai slum with a prostitute named Goong, his girlfriend. The conditions are squalid, the setting tropical, the heat sweltering, the breeze nil, the stench profound. Surprisingly, supplies of water and electricity are reliable.

The story divides along two lines that slowly merge as it unfolds: A series of twinned text messages from two women begins each chapter, one gentle and coaxing, the other abusive and hostile. The rest of each chapter consists of the narrator’s recollections of Goong, whom he abandoned, and their lives together on the narrator’s tab, paid, presumably via earnings from his writing (about what or for whom is never mentioned).

In exchange for the narrator paying Goong’s family’s bills, she has sex with him daily. She also comes to like him, for at least two reasons—his taking care of her family and his remaining devoted to her, a woman 20 years his senior. That’s one of his kinks. He’s a man of kinks, all of which—like his preference for older women—are harmless (save for the potential transmission of STDs).

He is either on a journey toward or away from salvation from a life of drink and whoring. While he prefers emotional and physical isolation from others (see also Chet Brown’s Paying for It), he is also saddened by harming Goong with his behavior. What remains ambiguous is whether, by leaving her, he is attempting to come to terms with himself in a way that would allow him to reunite with her or pushing himself to further pursue his encounters with ladyboys—which seems to be the point of contention motivating the story’s action.

New Juche is the pseudonym of a photographer and writer who works in Southeast Asia. (“Juche” is the term given to Kim Il-sung’s so-called “thoughts.” I assume the appellation is intended as humorously ironic.) He seems to be William Vollmann’s protégé: in general, regarding Vollmann’s writings on prostitutes; in particular, Vollmann’s time writing about and living with Southeast Asian prostitutes (see Butterly Stories, for instance). I’m a fan of Vollmann’s, so that’s a good thing.

The Tale of the Tiny Man

The Tale of the Tiny Man

Barbro Lindgren (Julia Marshall, trans.) with illustrations by Eva Eriksson

Gecko Press

A charming children’s story about a friendless man who looks like Mr Magoo (high, red, round cheeks pushing up against squinting eyes and a bulbous nose). Small, none-too-bright but kindly, the tiny man lives alone, ruing his loneliness. Then, one day, he is approached by a friendly dog who initiates play, which the tiny man reciprocates with food. The tiny man has a friend!

But after a year of this, a little girl comes by, and the dog is interested in meeting her, too. Has the tiny man’s friendship come to an end? Was “friendship” just a cruel illusion? Enquiring children will want to know.

Eva Eriksson’s illustrations are excellent at conveying the story’s changing moods, and Julia Marshall’s translation is graceful and natural sounding in English.

Genesis 0

Genesis 0

Isabelle Nicou (Katie Shireen Assef, trans.)

Amphetamine Sulphate

Isabelle Nicou is an introspective, self-interrogating writer in the mode of her French predecessors, Marguerite Duras and Annie Ernaux. In this terse novel, the narrator Elizabeth is a 30-year-old actress whose career has stalled, such that after years of acting, she is still only landing minor roles, such as Aricia in Racine’s Phèdre). Also stalled is her four-year relationship to Simon, a neuroradiologist, who seems to put in 18-hour days, seven days a week—when he’s in town. Worse, he doesn’t attend the plays Elizabeth acts in, and seems to have platitudinous attitudes towards the arts in general.

Career and relationship going nowhere are enough to reinforce the negative messages from her mother she grew up listening to, and still does, a mother who finds her own daughter to be a horrible person and finds nothing of value in the work Elizabeth does. (Her father merely ignores her.) All-in-all, a bad time to get pregnant.

The Beast and Other Tales

The Beast and Other Tales

Jóusè d’Arbaud (Joyce Zonana)

Northwestern University Press

Originally published in the Provençal language in 1926, this collection of five stories by Jóusè d’Arbaud describes the lives of gardians, a type of French cowboy of the country’s southern end, the land salty and marshy, good for raising bulls on. Demonstrating the unchanging duties and lives of the gardians, the time of the stories range from 1417 to the early 20th century, when cars for transportation are beginning to dominate over horses.

Set in Provençal, among its bogs, marshes, lagoons, and salt flats, “The Beast” follows the path of an old literary convention: The person presenting the story we’re about to read claims to be not its author but merely its editor, in this case, mysterious manuscript over 500 years old by one Jaume Roubard, kept secret from everyone he knew but passed along generation to generation by the eldest sons. The manuscript details Roubard’s encounters with a creature half goat, half man—an elderly demigod, an unwanted and feared beast, no longer worshipped as in pagan days, and slowly weakening in life force. “The Beast” is an extended ode to a land and the animals on it still haunted by their pagan past.

In “The Caraco,” a loner gardian, Pèire Guilhem, comes upon a young Caraco woman lost and hungry (the Caraco are described in terms similar to those used for gypsies: nomadic, clannish, and given to petty theft). Feeling pity, he takes her to his cabin and feeds her. She is allowed to sleep in the barn loft. Beginning the next morning, the Caraco, who is 16 years old, tidies his cabin and makes their meals. Guilhem finds himself happier than he’s ever been—but now the subject of teasing in the village because everyone knows a girl has moved in. (Note, the villagers aren’t upset by her age—they’re just waiting for a wedding invitation.) It’s a poignant story about a man who never before knew the depths of love and unhappiness.

We meet Guilhem again in “Pèire Guilhem’s Remorse,” where he has a side job supplying old horses for bull fights. When an old horse he used to tend is gored by a bull, he offers to pay to take the wounded horse back home. The offer of pay is something Guilhem cannot afford, as his (new) girlfriend reminds him. It’s her or the old horse. Will Guilhem’s choice matter?

Another Pèire features in the last story, “The Longline.” Although the life of a gardian is lived mainly alone, and although borders among ranchers are porous, a sense of privacy and ownership still pervade among the gardians’ notion of dignity. And although the gardian life is rough and nature unforgiving, a sense of morality also pervades each man’s conscience. Thus, when a stranger—who had been poaching Pèire Gargan’s fish—fails in his attempt to knife Gargan, Gargan kills the man in self-defense, and his shame haunts him as much as any conscience-torn character in Poe’s stories.

Video clip: translator interviewed about the book and author.

The Divorce

The Divorce

César Aira (Chris Andrews, trans.)

New Directions

I’ve read that César Aira improvises his novels, that nothing is planned. Whether true or legend, the circumstantial evidence for improvisation is there: a hundred or so novels, so far, each about a hundred pages, give or take. Long enough for an improviser to demonstrate his chops, short enough to not repeat himself or, worse, bore his audience. Even John Coltrane had to catch his breath sometimes.

Aira’s novels are based upon skimpy premises from which so many digressions hang that the so-called backstories are usually more important than the current actions the backstories are designed to explain. In the case of The Divorce, the novel is structured around the following events which take 98 pages to unfold:

After the narrator and his wife agree to divorce, he decides to take a month off in Palermo, Argentina, where he has acquaintances. While in Palermo, sitting at an outdoor café with a woman named Leticia, he watches the café’s canopy be emptied of rainwater, inadvertently torrenting down upon a passing bicyclist, Enrique, the landlord of the guest house he’s renting, who also happens to know Leticia. Nearby, at another table, Enrique’s mother also sees her see her son get drenched.

That’s it.

All else is backstory and digression. Here’s a small fraction of one of those digressions, this one regarding a friend of Enrique’s named Jusepe, whose childhood Sunday drives in his parents’ snug compact car were also accompanied by the Hindu god Krishna:

To be with Krishna was to become acutely aware of how many things there are in the world; after a few minutes it became overwhelming. Putting up with him for a whole afternoon could be torture. The pointing was accompanied by a ceaseless holding forth, for each thing had its name, and each name gave rise to what must have been (had anyone been able to understand them) puns, jokes, verses, and snatches of song, all of which made Krishna (and no one else) shriek with laughter. Everyone ended up with a headache.

The Divorce is one of Aira’s best improvisations.

Heart First into This Ruin: The Complete American Sonnets

Heart First into This Ruin: The Complete American Sonnets

Wanda Coleman

Black Sparrow Press

Originally published in sections across various of her poetry collections, Heart First into This Ruin finally collects into one volume the complete 100 American Sonnets, Coleman’s contribution to the sonnet form and the aesthetic expression of her experiences as a Black woman in America, un-degreed and unmarried—experiences simultaneously singular and familiar, unique and shared, compressed to 14 lines (the only formal element her sonnets share with traditional sonnets). The lines and stanza lengths vary from poem to poem, suggesting that Coleman tries to tailor each poem’s meter to its subject, the way it is talked about, described. And this she does very well, covering family, erotic love, work, chronic poverty, racism, and the damned knowledge that she is better than what she receives from American society.

Here’s Coleman in meditative form, “American Sonnet #76”:

there be the fog outside and the fog inside

settling over the gravesites and skin

climate fit for ghosts and amnesiacs, befogged,

intrusive skirtings thru filters, cracks

and secret spots, mist forming at my lover’s

kiss in the pretty air, the kiss hovering and diving

before it strikes me. mist oceanflow from resistance to

peace time, mist taking root in the brown chair at the

pine desk, composing, there is internal fog and external

fog. a garden of spirits and drums, sprites

thrilling on the ooze, of firs, walking naked, cold and

hungry for smoke, the east, want borne on wickedness like

a shot, or kiss, before diving into blankets and history

to embrace the fog to give it form and flesh

An essential collection of American poetry from the late 20th century. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F7wzNRf6mJs