Fran Shor’s recent book Soupy Sales and the Detroit Experience is an exposè on the Detroit media and cultural icon Soupy Sales. Through dozens of surveys and interviews, many by those directly connected with the 1950s program, Shor has amassed a short but significant contribution to the historic record.

Fran Shor’s recent book Soupy Sales and the Detroit Experience is an exposè on the Detroit media and cultural icon Soupy Sales. Through dozens of surveys and interviews, many by those directly connected with the 1950s program, Shor has amassed a short but significant contribution to the historic record.

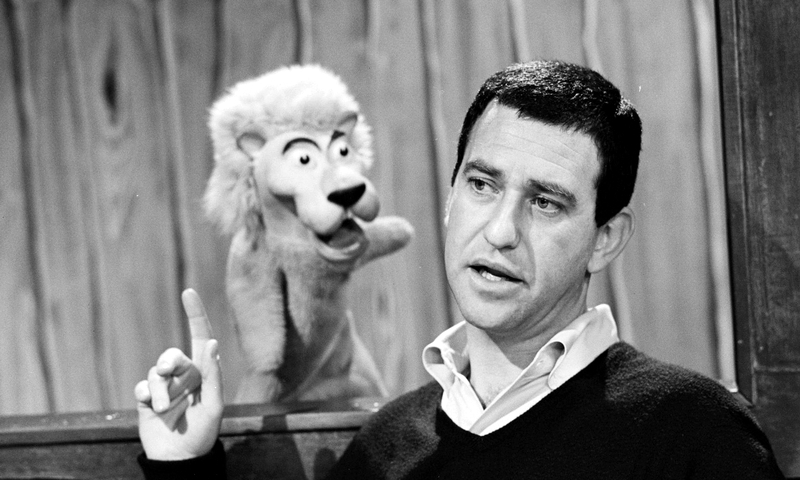

The book will have fans laughing and reminiscing over their own experience of sharing “Lunchtime with Soupy” or glued to the T.V. set before school days. Hilarious stories about Soupy sidekicks; White Fang, Black Tooth, Pookie, Hippy and others are also featured.

Shor has collected behind-the-scene anecdotes, wild gags, and photos, while also taking a serious look at the urban backdrop where Soupy’s zany humor and off-beat celebrity helped shape the Motor City.

Book Beat & Fran Shor Discuss the Soupy Sales and The Detroit Experience Live on Zoom

Pull up your TV tray and frozen dinner, focus back to your Soupy Sale memories, and join us for a public online Zoom discussion/meeting with author Fran Shor this Saturday, February 5, at 6:30 PM. Access the talk directly here at: Soupy Zoom

Published by Cambridge Scholars Press in the UK, copies of Soupy Sales and the Detroit Experience are available in store, online at our Backroom Gallery or at our affiliate page on Bookshop.org.

Q: You mention being a teenager when you first saw Soupy Sales on Pittsburgh television. I was wondering if that teenage experience had remained with you, or was there some other experience that had caused you to write the book? Why is now a good time to be discussing Soupy Sales and his television programing?

A: I think there are numerous reasons why certain past events, especially during the formative teenage years, remain resonant throughout one’s life. Certainly, the music of the 1950s and 1960s still elicits waves of nostalgia for baby boomers. Moreover, being retired (in 2014 from Wayne State after 40 years teaching there) and losing one’s father induces one to reflect on many moments in one’s life. For me, wanting to reconnect with those happier memories naturally included watching Soupy Sales and incorporating his schticks into my own goofy teenage years. Beyond my own personal experiences, investigating the cultural Zeitgeist within which Soupy operated allowed me to probe deeper into those larger conditions that shaped my generation.

Q: One of Soupy’s and standout qualities was his congenial, approachable, and “down home” southern personality. How do you see that integrated into his craft—and why do you think his act matured and was so well received here in Detroit?

A: Soupy often jocularly claimed that with a face like his (one that, alas, took thousands of hits of pies) he had to go out of his way to charm people. Using humor that drew on other comic television performers of the 1950’s (like Milton Berle, Pinky Lee, and Sid Caesar) and his own zany, but congenial, style, Soupy built a devoted following, especially in his breakout years on WXYZ TV in Detroit. Part of the reason that it may have appealed to Detroit kids and adults was that he brought that humor and congeniality into his daytime and evening television programming. He reinforced the television connections with hundreds of appearances throughout the Motor City at a time when being an approachable television personality was somewhat novel. Moreover, given many of the tensions of the times, having a silly “big brother” like Soupy was reassuring.

Q: Early in the book you cite Milton Berle and Sid Caesar as forerunners to Soupy’s comedy and toward the end of the book I was glad to see you quoted George Stewart, who mentioned the Ernie Kovacs and Mad Magazine as influential among the boomer generation. Can you speak on how these absurdist and anti-authoritarian styles became an influence not only in Soupy Sales, but in the anti-war and resistance movement? Do you find them still to be relevant?

A: The irreverence that Soupy and his cast of characters brought to the screen was a contrast with much of the other “children’s” programming at the time, especially the staid and conformist Mickey Mouse Club. Many of my interviewees who watched Soupy were influenced by the weird, almost Dadaesque, world crafted by Soupy and his colleagues. Added to this was an underlying anti-authoritarianism that existed during this period and would become formative for various social movements of the 1960s. I identify some of these strands in my other writings, from my discussion of white students in the Civil Rights Movement (in Weaponized Whiteness) to my own fictional representations in Passages of Rebellion. As Janis Ian sings in her recent song about “Resistance,” these political struggles unleashed in the 60s are still with us today.

Q: One of my favorite sections of the book is how you drew comparisons between the style of the Soupy Sales Lunch show and the Mickey Mouse Club. Those stark differences ring true at the root of our current political and cultural divisions—and they also seem ripe for further exploration. Could you go into that a bit more?

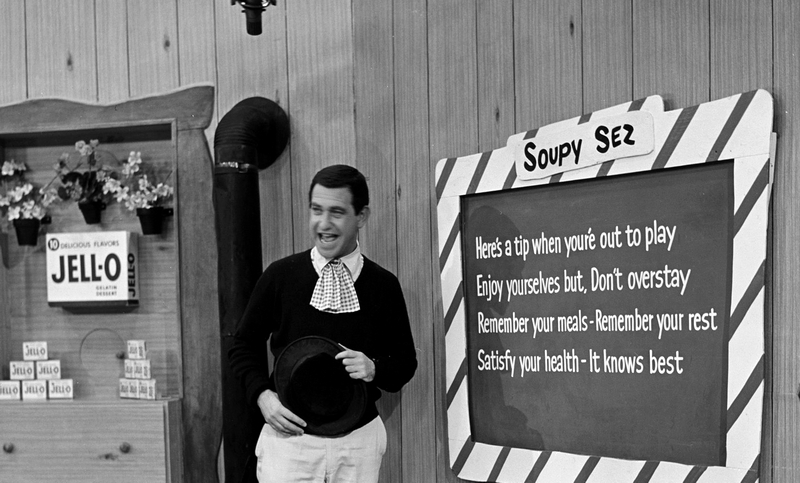

A: Indeed, the Mickey Mouse Club, with its scripted routines and scrubbed proper teens, stood out against the raucous humor and slapstick routines performed by Soupy during this same time in the mid to late 1950s. While Soupy studiously avoided references to politics and religion, he wasn’t above dispensing “Words of Wisdom” – “Be true to your teeth and they won’t be false to you.” In stark contrast, one could not miss the obvious religious and Cold War political messaging in the Mickey Mouse Club whether it was the sign above the Clubhouse door that read “God Bless the Mickey Mouse Club” or the special segment on “Inside the FBI” which highlighted the agency’s pursuit of subversive spies. While Soupy certainly wasn’t a spy, in many ways he was subversive of the kind of conformist values promoted on the Mickey Mouse Club. In today’s culture wars, Soupy would not be on the side of the white-bread Mickey Mouse Club, but more than likely a defender of the graphic novel, Maus.

Q: Another important section in the book was your chapter on bigotry and redlining here in the 1950s—a major difficulty for the African American community and how Soupy’s On and his late-night jazz programming helped break the color barrier on local television. You also suggest that the demise of jazz outlets and talent that left after 1960 was caused by the lure of greener pastures in New York City, yet many musicians stayed in Detroit and worked here for decades, even with fewer performance outlets. Do you see the deindustrialization of Detroit at the root of this brain-drain or were other factors at work?

A: As Tom Sugrue points out in his important book on Detroit in the post-WWII years, deindustrialization really begins in the 1950s as the auto industry begins to be suburbanized and move to non-union states. I incorporate his work, as well as that of Heather Ann Thompson and Daniel Clark on the socio-economic conditions in Detroit at the time where boom and bust cycles created certain opportunities for workers, both white and Black, even as the latter faced continuing discrimination in housing, employment, etc. What I found so intriguing, however, was the flourishing of jazz clubs and home-grown musicians who performed at those clubs and on Soupy’s evening program. Certainly, many of those Detroit-bred talents left for places like NYC because of greater recording and performing opportunities, even as some did stay.

Q: After Soupy made the decision to leave Detroit, it’s suggested that the creativity of his show declined, and never recovered. Was that due to his relying on the pie-in-the-face gag, lower creativity, or was control of his later shows given up to tighter corporate oversight?

Q: After Soupy made the decision to leave Detroit, it’s suggested that the creativity of his show declined, and never recovered. Was that due to his relying on the pie-in-the-face gag, lower creativity, or was control of his later shows given up to tighter corporate oversight?

A: I don’t think Soupy’s creativity flagged when he went to LA and NYC. However, the station managers and owners were more attuned to corporate decision-making and bankable programs than what Soupy encountered during the 1950s in Detroit. I explore what Soupy retained and what he developed in my chapter on “Detroit Afterimages” about his time in LA and NYC.

Q: The low budget “club house” style of the Soupy Sales’ set and props became ubiquitous in children’s programing by the early 1960s, yet Soupy’s clubhouse retained a subversive edge that was unique and outside most other programing. Soupy’s style was revived in Pee-wee’s Playhouse from 1986-1990, one of the weirdest and wildest children’s programs ever, and a counter-culture artifact. Both programs broke down the barriers and walls between the viewers and set. Hosts and guests often spoke directly to the audience. Was that something Soupy pioneered, and can you recall some examples of that in practice? Do you see a time for programming like that to return again?

A: While a few other television comedians of the 1950s talked directly into the camera, eg, Jack Benny, Milton Berle, George Burns, Sid Caeser, etc., Soupy made it such an integral part of his daytime routines, from speaking directly to his “Birdbath” audience and fans to mugging after getting hit with a pie or engaging in silly wordplay. Breaking down the “fourth wall,” as it was often called has become a common trope in films (eg. Woody Allen’s comedies) and late night talk show hosts’ monologues. Soupy certainly did utilize and popularize that style beyond what anyone else was doing at the time. That may be one of the many reasons that he still retains such regard and love among his viewers from this period.

[The Q & A above took place by e-mail between author Fran Shor and Cary Loren of Book Beat on Jan. 30, 2022.]

About the author: Francis Shor is an Emeritus Professor of History at Wayne State University. He is the author of five non-fiction books, and a novel, Passages of Rebellion (Outskirts 2020). Other publications, covering a broad range of topics in 20th century U. S. and global history, have appeared in scholarly journals and popular online journals. In addition to his academic work, he has been a long-time peace and justice activist, serving previously on the Boards of Peace Action and Michigan Coalition for Human Rights (MCHR). Presently, he is an Advisory Board member of MCHR and on the Board of the Congregation for Humanistic Judaism, where he also co-chairs the Program Committee.