Tom Bowden is a local reviewer, educator of the Chinese language, and cultural mavin, who has been reviewing eclectic and important small press books and works in translation for the Book Beat newsletter since the pandemic. Bowden’s regular monthly column “i arrogantly recommend…” has been a work of love we greatly appreciate. We link his reviewed books to our affiliate shop on Bookshop.org/ a service that benefits independent bookstores from around the country. Books can also be ordered directly from us at BookBeatOrders@gmail.com or by calling us at (248) 968-1190 or visiting our shop at 26010 Greenfield in Oak Park.

Stalingrad

Stalingrad

By Vasily Grossman [Robert Chandler and Elizabeth Chandler, translators]

NYRB Classics

Vasily Grossman—who witnessed Stalingrad’s devastation during WWII and talked to its citizens and soldiers—wanted to create a panoramic epic of the war equal to Tolstoy’s War and Peace with a theme equal to that of War and Peace. The scale is large—multigenerational, multi-ethnic—though occurring over the space of a single summer, encompassing social rank as well as moral, ethical, and political duties at the risk of life. Heroes walk here, as do cads. Love is known, kept, and lost. Being an admired character does nothing to sustain a character’s life—we, too, lose what matters to us.

Stalingrad begins after the start of WWII and Hitler’s assault on the USSR, Germany troops quickly and easily slicing through Russian territory, with little significant resistance. Before the siege of Stalingrad, we are introduced to characters from various parts of the union—returning home from the front, leaving home for the front, staying behind to help the war effort, and so on—from cities to countryside, from farms to high-ranking military offices. Sons, daughters, grandparents, grandchildren all strive to exist under extreme conditions, as do factory workers, farmers, soldiers, nurses, and doctors—male and female alike.

Actual fighting takes up a smaller portion of this 900-page brick (closer to 1,100 pages with notes and afterword), and the novel ends before the siege. (Part 2, Life and Fate, another 1,000-pager, picks up with the same (remaining) characters of Part 1 after the siege.) Despite Grossman offering this tome as an homage to Russian bravery, Soviet censors managed to be offended by the original manuscript, which underwent revisions before it was able to be published—after Part 2. Stalingrad’s translators, the Chandlers, have done their best to re-create the ur-text submitted by Grossman. Since I am not a student of Russian language, literature, or publishing practices, I cannot measure their achievement in those regards.

However, as a novel in the Russian capacious tradition of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky (authors of differing temperaments) and the 19th-century Western European practice of cranking out 700-900-page books, Stalingrad fits well while also extending the tradition. Although I’m tempted to now pick up the copy of Life and Fate that has sat unread on my shelves for decades, Robert Chandler, in his afterword, says that he is contemplating re-translating it, since he now has available manuscript pages that were inaccessible before the fall of the Soviet Union. An excellent companion to this novel would be Svetlana Alexievich’s non-fictional Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II.

Peach Blossom Paradise

Peach Blossom Paradise

Ge Fei [Canaan Morse, trans.]

NYRB Classics

“Let a thousand flowers bloom.” —Mao

Magpie brought the cicada to the pawnshop, but the pawnbroker wouldn’t take it. In fact, he wouldn’t even look at it twice. He stuffed his hands in his sleeves and said dully, “I know it’s gold. But gold isn’t worth anything when people are starving.”

“A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths are statistic.” —Joseph Stalin

The hermit’s hedgerow is like the Peach Blossom Paradise:

After these flowers blossom, no others will bloom.

An old Chinese tale describes a remote spot stumbled upon by an outsider, who discovers a perfect place where all people and creatures are in harmony with each other, Peach Blossom Paradise. After his stay, he returns home, describing the paradise he discovered. Some dismiss his stories; others try but cannot again find the place described. Ge Fei weaves this tale with another search for Paradise on Earth, a pre-Maoist Communist Revolution that in part promises to liberate women from the tyranny of arranged marriages—so that any man can fuck any woman he wants at any time.

Xiumi, the novel’s protagonist, is around 12 years old when the book starts. Her father is a government functionary, and thus part of the upper class—an estate with land plowed by others and a house with live-in maids. He apparently goes mad, and just walks away from home one day, never to return. One doesn’t need to know about the violent tumult across China resulting from the late-19th century Hundred Days’ Reform to appreciate the shock and confusion among isolated rural communities far from any hub of reactionary or revolutionary turmoil about what is going on.

By age 15, Xiumi’s mother is almost out of money to run the household and sells her daughter into an arranged marriage. En route to her fiancé’s estate for the marriage, Xiumi is kidnapped and taken to an island while awaiting ransom. But neither Xiumi’s mother nor her fiancé is willing to pay her ransom, and thus the kidnappers rape and sell her off to another man. Passed among government officials and criminal kingpins, Xiumi learns ruthlessness and gains revenge. Perhaps worse, she also gains an ideology. Talk of revolution permeates the air, but when the characters in this novel ask each other what “revolution” means, the only working definition that they can guess at is “the ability to do whatever I want.”

While I was reading Xiumi’s transformation into a nightmare, and understanding the forces that shaped her, I came across a review of Alex Kotlowitz’s An American Summer: Love and Death in Chicago (“How Can We Stop Gun Violence?” by Francesca Mari (NYRB, June 10 2021)), that focused on Kotlowitz’s descriptions of a young man, Thomas, with post-traumatic stress disorder brought on by the many murders Thomas had witnessed since he was 11 years old—friends, family, strangers. He is in a constant state of high-tension anger and anxiety. The only thing that quells it is violent release, which allows him to finally sleep.

Xiumi’s ideological vengeance—her violent release—ends with the death of her six-year-old son, whom she had never even bothered to name, consumed as she was by her revolutionary furor. The last quarter of the book regards Xiumi’s atonement and repentance, largely by heeding Voltaire’s advice to tend her own garden. A sense of redemption and grace concludes the book.

Ge Fei is an excellent writer, with a talent for empathy, depth, and subtlety. This is only the second book by him recently translated into English, and it’s the best novel I’ve read so far this year. Translator Canaan Morse has a keen eye for key words and phrases deployed and developed throughout the novel, echoing its themes: the dangers of ideologies, the fact that ideologies are rarely women-friendly (even in the hands of women), and the need and ability to recover from ideological delusions—“recovery” including humility and selflessness.

A Man’s Place

A Man’s Place

Annie Ernaux [Tanya Leslie, trans.]

Seven Stories Press

A memoir, biography, and homage to her father, Ernaux explores her upbringing in rural France by a man—the main motivating force of the family—who rose from poverty to the American equivalent of lower-middle class stability.

Without romanticizing any of his past, Ernaux describes her father’s birth into the French equivalent of sharecroppers: Workers of other peoples’ land for poverty wages and little respect. Her father, she points out, was pulled out of school just days short of obtaining his elementary school certification. The family’s reason was based on necessity: Now that he was 12, the landowners would not allow him to sleep in the house or feed him without pay. Ernaux’s grandfather could not afford his son’s room and board, and so it was off to the barn loft with him, with nothing but hard life ahead.

Ernaux implies that she was on the outs with her father during her teen years, as she grew closer to her mother and he grew impatient with her teenage behavior. Typical of Ernaux’s essays is an attempt to look as issues with eyes as cold as possible—a French Didion, though of a different temperament and outlook. As a result, Ernaux focuses on her father’s actions and their outcomes rather than the emotions they evoke; she recalls the phrases her father and mother emphasized time and again, drawing attention to how much she has internalized them in her own way of thinking and writing, even if just ironically; his commitment to modesty even when, well into middle age, he becomes the first person in his family to own property—a small shop and house that he and her mother ran for many years.

Despite his gruff exterior, he made sure his daughter got as much education as she qualified for, and never at his or his wife’s insistence. Ernaux went to college to become a teacher, and two months after she passed her qualification exam, her father died.

Can the Monster Speak?

Can the Monster Speak?

Paul B. Preciado

Semiotext(e)

[G]ender transition . . . entails activating those genes whose expression had been thwarted by the presence of estrogens, by connecting them via testosterone and triggering a parallel evolution of my own life, by giving free expression to the phenotype that would otherwise have remained silent. To be trans, one must accept the triumphant irruption of another future in oneself, in every cell of one’s body. To transition comes down to understanding that the cultural codes of masculinity and femininity are anecdotal compared to the infinite variety of modalities of existence.

In 2019, Paul B. Preciado was invited to give a talk to a convention of 3,500 Freudian psychoanalysts in Paris—a talk that was jeered at by the Freudians, denounced, and shouted down before Preciado was even half-through. Not a single member of that group from Ecole de la Cause Freudienne would even admit to, for instance, being gay, when asked, a way of being the group asserts is pathological.

The entirety of Preciado’s speech has now been translated and published. Preciado, a trans man, has studied the history of psychology and legislation as it relates to defining “normality,” and finds it still primarily based on masculine identity and genitalia. Even women, according to these Freudians and Lacanians, are a sub-species or lesser example of the male ideal.

Gore Vidal in an essay once alluded to Freud as a Viennese novelist—no science, no research, just unexamined assumptions, and a hostility toward evidence (richly abundant from his own patients) at odds with his unsupported assertions. Lacan was even less of a scientist than Freud, even less of a writer, but couched his prose in dense absurdities difficult to unravel. (For those who made the effort to unravel his essays, the hard work revealed only unsubstantiated nonsense at its core.)

By defining what characterizes “male” and “female” and positing heterosexuality as the only nonpathological way of living and loving in the world, Freudians helped shape and determine the legal context in which people may be arrested, jailed, forcibly medicated, raped, operated upon, kept from employment, and so forth.

Just as Ptolemy and Galileo helped decenter the Sun, Earth, and humanity from Center of the Universe to small corner of an unremarkable galaxy among trillions of others, the notion of what it means to be human is undergoing a profound shift in understanding what is at the core of our being, no matter our genitalia, reproductive capacity, or preferences in intimacy. Living in a small corner of an unremarkable galaxy makes us no less human than before (or any less the children of God to theists)—any more than existing on a continuum of physiology and desires does.

William Burroughs, in The Book of Breeething [sic], argues for using the “as” of identity rather than the “is,” as shown in Egyptian hieroglyphs. In these hieroglyphs, the “as” of identity describes people according to functions they perform: X as uncle, as brickmaker, as citizen, etc. “Is” labels, however, are prone to limiting bigotries. The “is” of identity assumes that everything significant about that person is revealed by biological descriptors. For instance, “X is gay” (or Black or Jewish, etc.): “That’s all I need to know about him!” Preciado convincingly argues along similar lines for a human emancipation that frees us from destructive, limiting notions of what it means to be fully human to productive, varied, and affirming notions of existence, unshackled from genital obsession.

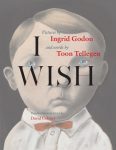

I Wish

I Wish

Ingrid Godon (picture) and Toon Tellegen (words), David Colmer (trans.)

Elsewhere Editions

Ingrid Godon and Toon Tellegen have separately won many awards in their respective fields. For I Wish, Tellegen added brief thoughts for each of the characters depicted in a series of portraits by Tellegen. (It isn’t clear to me whether Tellegen or Godon named the portraits.) The match is excellent, and the pairings of text and image often devastate with their ingenuous simplicity, especially since most of the portraits seem to be of children, whose wide-set eyes and closed lips suggest mild unhappiness or befuddlement.

Almost every pairing begins with the words “I wish,” such as these, from “Susanne”:

I wish I wasn’t scared of dying.

There are people who aren’t scared of death.

When they see him coming they just stand there

calmy and call out, “Hey, Death!

It’ so nice to see you!”

But those same people hide in the basement during

thunderstorms or scream and climb up on tables

when they see a mouse.

I like mice and thunderstorms.

Maybe everyone needs to be scared of something,

it doesn’t matter what, just like everyone needs

to breathe and eat and drink.

Otherwise you die.

And from “Carl”:

I wish happiness was a thing and I

found it somewhere and took it home with me.

I wouldn’t tell anyone I’d found it.

I’d hide it and only get it out

when I was sure I was completely alone.

Then I’d buff it up.

Happiness needs to shine, even if it’s secret.

If I felt down and nothing I wanted was working out,

if everyone hated me and I was in the hospital with two

broken legs, boils, toothache, conjunctivitis,

chicken pox, and scarlet fever, I could tell

myself: but I still have my happiness,

it’s still there where I put it!

Each vignette represents a way of looking and understanding the world and one’s place in it—or being at a total loss to figure out what that place might be.

While I defer to the expertise of those who target the book to 8–12-year-olds, I suspect that I Wish is a type of book adults tell themselves they wish they had at that age for its examples of other kids who were dealing with the same doubts and hopes. But the likelihood is that, when these same romanticizing adults were kids, I Wish is exactly the type of book they would have ignored since its coolness is not immediately obvious. I Wish seems pitched to an emotional level I don’t recall myself having from 8-12, nor is it one I see among the few 8–12-year-olds I do encounter. Fourteen- to sixteen-year-olds, yes—but this isn’t a graphic novel or manga, so the kids interested in this book—for all its qualities—would likely be among the 10% whose emotional maturity is ahead of their peers. That said, I think adults rueful of their past will be those who appreciate this book most. If 8–12-year-olds would appreciate it, too, all the better!

Chartwell Manor: A Memoir

Chartwell Manor: A Memoir

Glenn Head

Fantagraphics

When Glenn Head was 13, his parents decided to send him to a small, private school to repeat the 7th grade. Over the years, Head had become increasingly distractable from school tasks and he was just eking by scholastically. Discipline was needed, and his parents chose to send Glenn to a boarding school for “troubled boys” (mostly), ages 5 to 15—usually boys from wealthy families, since tuition was $10K—a hefty sum in the early 1970s.

Every boy’s nightmare comes true in this book: The headmaster (who demands to be addressed as “Sir”) spanks, paddles, canes, beats, molests, and fellates the boys. (Who gets what is, as is usually the case in these situations, purely arbitrary.) The boys are trapped in a molester’s dream scenario: youth—troubled, confused, rejected at home—given unstinting attention and emotional manipulation that combines the shock of violence with the comfort of hugs and loving coos. This, at age 13.

That’s the first part of the book. The second part deals with the after-effects of those years. The after-effects, until age 30, include seemingly non-stop drinking binges, porn/sexshop/strip club binges, and—surprise!—difficulty maintaining relationships. Bonus points: Semi-estrangement from his parents, who turn a deaf ear to their responsibility for submitting their son to the abuses of the school. (The parents already seem to know or intuit that “Sir,” a tawny ex-Brit in his 40s, is abusive, and it’s nothing they care to give much thought to.) Head and I are, I would guess, within a year of each other’s age. Our parents are of a generation that says, “Deal with it. It happened; you can’t change anything. Move on,” while remaining blinkered to what that mindset has done to themselves, let alone to their children and grandchildren, while the effects of their decisions ripple on throughout the generations.

The indifference and willful obliviousness to molestation and other forms of abuse of one’s own child and of one’s own friend only worsen the emotional realm of the abused: To hear laughter as response to physical violation is a second violation of a child’s fundamental trust in the world. Head, in later years, meets up with some of his old school pals from Chatwell Manor, after Lynch, the headmaster, has been thrown in jail for pedophilia. Head gives up drinking at age 30, joining AA, but certain unhealthy sexual obsessions remain. Knowing how fucked-up he is as a direct result of that one year, he’s curious to see what’s happened to them.

None of the other three seemed to have made much of their lives: drunk, in jail, unemployed, etc. One is an especial car-wreck: drunk, missing a front tooth, part-time carpenter. That’s the first part. Part two: admits to enjoying Sir’s spankings and blow jobs. Part three: Hints that he’s seriously looked into the cost of having Sir killed by professionals. This is the notion of “resilience” of our parents’ generation.

Throughout Head’s memoir, at different years in his adult life, we see an image of Lynch on his drawing board, representing Head’s different attempts over the decades to confront his fears and their source. Each time results in emotional tailspin, almost always self-destructive. In Chartwell Manor, Head seems to have finally purged himself of the evil spirit that plagued him for 50 years.

Batlava Lake

Batlava Lake

Adam Mars-Jones

Fitzcarraldo Editions

Barry Ashton is a civil engineer deployed to Kosovo with the British Army after the civil war there in the 1990s. He’s a bit of an ass—a dull-minded bureaucrat who imagines himself as rational, ticking off boxes on administrative forms, taking special pride in being “[q]ualified under the Safety Rules Procedures to inspect premises and equipment and to give the go-ahead for service personnel to undertake their duties.” A strictly-by-the-rules type as unimaginative and unreflective as you might expect—a casual bigot, indifferent to and/or confused by duties of marriage and fatherhood, a man of principle unless those principles put personal life at stake.

An unsurprising result of this set of traits is the disdain by which he is held by the army men forced to salute him and follow his orders, and by his wife back home who divorces him midway through his appointment in Kosovo. Oblique spoiler alert: Hints are dropped throughout the story about how well Barry performs his job, details I didn’t recognize were clues until the end, and then I thought of Raymond Carver’s story “So Much Water So Close to Home” (1981).

I’ve known and worked with people like Barry Ashton, people who valiantly attempt to become two-dimensional examples of humanity via a steady application of “rationality”—itself a concept too many people base upon wholly unexamined assumptions, allowing for evading personal responsibility. It is to Mars-Jones’s credit that he is able to restore Barry’s tragic third-dimension and by so doing highlight Barry’s significant moral failings.

Ennemonde

Ennemonde

Jean Giono (Bill Johnston, trans.)

Archipelago Books

Although originally published in France in 1968, set in France’s rural “High Country,” and beginning roughly World War I, much of Jean Giono’s Ennemonde sounds like present-day U.S.: a mash-up between Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County and the average Trump supporter.

“The tool that people around here have most often in their hand is a shotgun, whether it’s for hunting or for, let’s say, philosophical reflection; in either case, there’s no solution without a shot being fired. . . Monsieur Sartre would not be of much use here; a shotgun, on the other hand, comes in handy in many situations.”

“It’s not that these folks are worse than others; it’s that, individualists to an extreme and incurably solitary, they’re constantly afraid of being duped. And if love does that often (makes you a dupe), hatred never does; there you’re on solid ground. I love you: that’s never sure; proof is needed. I hate you: that’s solid as gold bullion.”

“The Protestants of these parts had since time immemorial protested against Protestantism. They’d ended up worshipping anything at all, so long as the anything at all demanded intolerance. Crown of thorns were consumed in every household, at every meal. Religion was a sort of commerce in which discomfort was always preferred to joy, scorn to pleasure, and ultimately vice to virtue.”

Violence, hatred, and discomfort are forces of nature entwined with nature—animal, vegetable, and weather-driven—red in claw and tooth and the ultimate arbiter of truth, unforgivingly so.

Ennemonde is the story’s titular heroine, a toothless obese woman (280 lbs.), honest but otherwise amoral. She struggles for and wins unstinting respect from the folks in her area, buying, selling, and raising sheep. Giono clearly respects and admires Ennemonde, too, for all her amorality. Her fight for respect in a male-dominated patriarchal world is not a feminist battle—Ennemonde would destroy any woman who stood in her way, as well. Giono’s argument is that anybody who wanted to achieve Ennemonde’s modicum of material comfort would have been required to do the same.

Ennedmonde’s way—nature’s way—is not to ostentatiously shove others aside. That sort of arrogance, coming from either men or women, will be met by the community with resistance and will be shortly put down, one way or the other. Instead, the way to success is through silence and cunning, as Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus would have it (exile is to be avoided). The High Country consists of subsistence-level shepherds, either with small families or living by themselves in one-room huts, hidden in dales beneath trees. Reputation matters more than money, and everybody knows each other’s business by what they hear, see, and smell in the wind. Revenge may take decades to arrive and appear in the form of the natural consequences of farm life.

In the second part of the book, an addendum of sorts, Giono seems to build a case for Ennemonde being a natural conclusion from the environment of the High Country, not a one-off. Thus, Ennemonde’s decisions to disrupt legal, ethical, and cultural traditions make sense in a world that never even pretended to uphold notions of Christian morality.

Mrs. Murakami’s Garden

Mrs. Murakami’s Garden

By Mario Bellatin (Healther Cleary, translator)

Deep Vellum Publishing

“[On their wedding] day, Izu and Mr. Murakami ate alone in a restaurant on the outskirts of the city. It was the only time they would do this after Izu left home. The menu included a dish of flesh sliced from a live fish. The meal was served beside a glass dish containing the fish, and lasted exactly as long as it took the poor creature to die.”

Mario Bellatin is an author new to me but one who apparently has a least six previous books available in English translation. I’ll now make a point of tracking them down. Mrs. Murakami’s Garden exemplifies understated narration that allows the rhetorical effect of implication to knead each reader’s imagination into picturing the emotional ugliness implied. This restrained narration is a trait of much Japanese literature I’ve read. Thus, in terms of simulating the rhetorical tone of (some) Japanese literature, Garden is a stunning success, especially in terms of (a) a Mexican writer imitating (b) a trait of Japanese literature that is (c) successfully conveyed from Japanese via Spanish into English.

In addition to that rhetorical nicety is the subtle twist that turns the protagonist, Izu, from liberal to conservative, yet pariah to all. The transformation is morally horrifying, even though nobody fundamentally changes—only our perceptions of them change because of where the logical conclusions of their worldviews lead them. Playing the long game is Mr Murakami’s standpoint, with sadistic humiliation as its goal.

In weird contrast to the cruelty of the end narrative are the author’s “Addenda” and the translator’s “Note,” which are brief exercises in absurdity. Together they seem to annul the slow-burn seriousness of the story; but I suspect there are dots I’m failing to connect.

Little Snow Landscape

Little Snow Landscape

Robert Walser [Tom Whalen, translator]

NYRB Classics

“The desire and passion for sketching life with words stems finally only from a certain precision and beautiful pedantry of the soul that suffers when it has to witness so many lovely, vibrant, urgent, transitory things flying off into the world without having been able to capture them in a notebook. What endless worries!”

As with Bolaño—but for more years now—Robert Walser is a writer with a higher rate of post-mortem publishing than lifetime publishing. In Walser’s case, it’s not just a matter of making available in English his previously published works, it’s also a matter of publishing newly discovered manuscripts and manuscripts that could not be read until the “code” Walser employed could be cracked. (The code turned out to be an old German letter script written at a “microscript” scale small enough to write an entire novel on a single sheet of paper that was (as I recall) similar in size to a sheet of legal paper. There are 570+ plus sheets of various sizes in the Walser Archive.)

While at least 3,700 pages of published Walser exist (in the 1985 version of the complete works), the translation tap is set to about 150-180 pages a year in English. And the pages continue to impress, especially in the capable hands of a good translator, as we have here with Tom Whalen, who—like Susan Bernofsky and Christopher Middleton—are aces at replicating the nuances in Walser’s prose, which often have the feel of forced cheerfulness, of someone battling between optimism and resignation, elation and offense.

The stories gathered in Little Snow Landscape, arranged chronologically, follow Walser from 1905 to 1933, four years into the institutional living in which he would remain until his death in 1956. Let a couple of lines stand for some of Walser’s tics, one of them being to comment on the quality of his writing while he’s writing: “The sky had the deep, blushing-with-joy blue of a little frock fluttering around pretty legs, which without doubt constitutes a rather serious contemplation of nature” (from “Fragment”).

In “Wenzel,” Walser describes a person of a (self-defeating) mercurial temperament, another Walserian tic (cf. Jakob von Gunten). In this case, Wenzel is someone whose sudden ardor for acting is challenged when he receives his first role. “Wenzel is to play a prince’s lackey who, among other things, has to take a slap in the face. No, that he cannot play, that’s too deplorable. . . He absents himself from the performance, it’s too stupid.” But finally, Wenzel tells himself, “‘Love and ardor endure everything, even a slap in the face.’” And that’s pretty much how Walser lived his life: talking himself into love, becoming suddenly offended by the love, leaving the scene, and regretting his behavior with the ambivalence with which he fell in love.