Students of Myself

Students of Myself

Rhys Hughes

Elsewhen Press

The students of this short novel’s unnamed narrator are not acolytes but undergraduates of a required course: required of the narrator to teach, not for students to take. Few students enroll since the topic of the course is himself. He’d rather teach ecology.

The book consists of the students’ essay assignment and the narrator’s comments between groups of papers. The topic requires students to describe what they surmise he does in his free time, something he has scrupulously avoided discussing in class.

Before he gets too far into the essays, however, he notices some activity of the roof of his apartment building—a roof only accessible from outside. Events reveal a connection to the course he teaches and the consequences of his (and his students’) dissatisfaction with the class. Anything more added here would be telling.

Hughes clearly enjoys writing, does well at it, and likes working within constraints—whether those are the constraints of a genre or that he creates for himself—and with puns and repartee. With Students of Myself, one of the challenges is to create nineteen versions of the narrator (the students plus their professor) that more or less agree with each other—a large Venn diagram of nineteen circles—and then superimpose a plot upon what should appear to be random speculative information about the professor. Fun, inventive, and intelligent entertainment.

Interview with Rhys Hughes,fantasy writer of nearly 1,000 interrelated stories and 7 novels.

I’ve only read two of your books so far (Weirdly Out West and Students of Myself), and part of what I’ve seen in them is a joy in playing with constraints. That hunch about your work was confirmed by the entry on you in Wikipedia, which mentions several of your OULIPO-influenced works. (I’m a fan of all things OULIPO.) When does the method / constraint strike your imagination—before or after an idea for a story? How often do story ideas and their constraints occur simultaneously? Do you have list of constraints that you want to try out, and are just waiting for the right topic to come along?

Only a small percentage of all my prose fiction is OULIPO-based. I am going to say about 15% and no more than that. It’s very difficult to write such texts and whereas the mathematical constraints involved can push the imagination in unexpected lateral directions, resulting in great originality, this benefit comes at a price, which is that flow, inertia and smoothness are often compromised. The best OULIPO works are those that can be read as straightforward fictions as well as experiments with mathematical form. The genius Georges Perec could do that but I’m not sure that I can. At least I don’t think I have reached that stage, which is hardly surprising, as almost nobody has. Those two books of mine you mention contain complex patterns but they aren’t consciously OULIPO. They just have some inbuilt symmetry.

When I resolve to write an OULIPO work I decide on a constraint or series of constraints first, and then I write the story. I might use four, five or more constraints in one piece, occasionally superimposing them, or I might stick to just one, whether it’s an established constraint or one of my own. I am fascinated by OULIPO but at the same time I am aware that the rigidity of the constraints can be a hindrance to other qualities in a story. We don’t read this kind of fiction primarily for plot or character but simply to see how ingenious the author has been in constructing the form of the piece. The key moment for me, I guess, was when I devised my own constraint, one I call “?(2n+1)”. Writing fiction that utilized this constraint was a very big challenge.

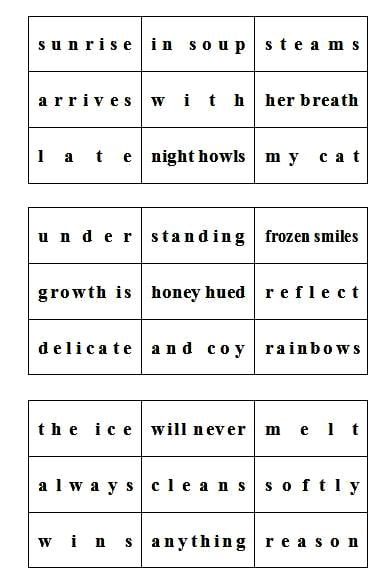

Essentially what this constraint does is generate grid stories that can be read along any row, down any column, across the main diagonal, and sometimes across other diagonals, and make sense in every instance. I learned a lot about the manipulation of words from experimenting with this constraint, about homonyms and words that must serve multiple functions, sometimes acting as a noun, other times working as a verb, and so on. My early experiments with this constraint can be found in my book How Many Times? First, I used grids that were symmetrical, but then I progressed to asymmetric grids, weird shapes that seemed to generate stranger and stranger stories. I am happy with what I have done, but as I said earlier, I don’t use this constraint or any others very often. They are too taxing. They are like constructing chess problems.

Essentially what this constraint does is generate grid stories that can be read along any row, down any column, across the main diagonal, and sometimes across other diagonals, and make sense in every instance. I learned a lot about the manipulation of words from experimenting with this constraint, about homonyms and words that must serve multiple functions, sometimes acting as a noun, other times working as a verb, and so on. My early experiments with this constraint can be found in my book How Many Times? First, I used grids that were symmetrical, but then I progressed to asymmetric grids, weird shapes that seemed to generate stranger and stranger stories. I am happy with what I have done, but as I said earlier, I don’t use this constraint or any others very often. They are too taxing. They are like constructing chess problems.

I’ve heard that many members of the OULIPO are (or were) also mathematicians. You’ve taught maths, too, is that right? What is it about systems of constraints that attract the mathematical mind, or at least yours?

We are to some degree led to believe that science and art doesn’t mix and that one can’t be, for instance, a writer of humorous fantasy tales and also interested in number theory, but this is nonsense, of course. Numbers are fantastical and magical in their own right, and they can be funny too. Anyone who doesn’t think that numbers can be funny just needs to read about Belphegor’s Prime . It’s hilarious!

Mathematics is one of the few subjects I was good at when I was at school, but I didn’t excel at it, I was just better at mathematics than I was at most of the other things I had to learn, and at university I had a brilliant professor who taught the subject in such a way that it seemed exhilarating and almost easy. The founders of OULIPO were true mathematicians, not amateurs like myself, and the reason I say I am an amateur even though I teach the subject is because I haven’t done any original work in the field, nor am I ever likely to. It’s too difficult.

But mathematics gave me my first taste of publication. I designed chess problems and mathematical puzzles for newspapers. Most of these puzzles were based on geometry rather than algebra and that has always been the branch of mathematics that has appealed to me most strongly. I have written stories in the shape of tesseracts, for instance. What I mean by this is that I have imposed the rules that govern the two-dimensional representation of a hypercube onto works of fiction, so that the tesseract has eight equal sides when displayed in this fashion and therefore a story must have eight characters of equal significance. The internal connections of the diagram will define how these characters interact with each other. This is just one example out of many.

But not every constraint is necessarily abstruse. Some are simple, but the fact they are simple doesn’t mean they aren’t tricky to apply. I’m planning soon to write a story called “The Prime of Our Lives,” in which there are a prime number of paragraphs, and each paragraph contains a prime number of sentences, and each sentence contains a prime number of words, and each word contains a prime number of letters. Even finding a title for this piece was a chore because the title has to follow the rules too. The story will also feature prime numbers as protagonists. My hope is that this piece will eventually be included in a collection called Your Number’s Up, which will feature not only OULIPO stories but stories that are experimental in other ways and have nothing to do with mathematics. I’m in no rush to complete this project.

From your Facebook posts, I gather that you’re nearing your goal of completing 1,000 inter-related short stories. Congratulations on what you’ve achieved so far. On what basis or bases are the stories inter-related, and is there an ideal sequence in which they should be read?

When I began writing short stories, I had no notion that I could link them all together into one big story cycle. That realisation came later. I had already written one hundred stories before I decided that with little linkages, with allusions and references and in-jokes, I could spin some sort of web that would connect all my work. But it’s a rather ragged web because some of the stories aren’t properly linked yet. I am working on doing this. For the early tales it is easy enough to pressgang them into the big story cycle by having a character pop up in another tale. To link, say, five unrelated stories can be done easily enough, by writing a sixth story in which characters from those five stories all appear together. There are difficulties of continuity then, of course, but I have found a way around this too. The idea is that there is no best sequence in which they should be read. A reader shouldn’t even notice that a story is connected to any other story, although some stories do form mini-cycles that work better when read in order. All the stories, or most of them, must absolutely operate as standalones as well as parts of a greater whole, otherwise I have failed to do what I intended with this big cycle.

Why did I decide to write a story cycle of 1000 stories in the first place? I am not entirely sure. I suppose it has something to do with The Thousand and One Nights, which I read in abridged form when I was a child. I have been told, and I am forced to concur, that authors often make a mistake when they retroactively try to fit all their earlier work into one big and definitive vision. James Branch Cabell is often held up as a good example of this process going wrong. By fitting everything he wrote into one sequence, the good is mixed up with the bad, to the detriment of the good, never the enhancement of the bad.

That may well be so, but it’s far too late for me now. I have nearly written my thousandth story, the big cycle is nearly done, for better or for worse this thirty-year project will be over soon. Was it worthwhile? That is not really for me to judge. Thinking about it, I suppose that another big influence on my decision to link everything together was the work of the fantasy maestro Michael Moorcock, who has been doing this for decades, with whole novel sequences rather than just short stories. Of course, the entire thing can be messy and some of the linkages just aren’t convincing but on the positive side it can be very satisfying for a reader to encounter a scene or a situation in one book that is partly the resolution of the action in another book. That does sometimes happen. And it’s a perfect medium for in-jokes and intertextual games, which some readers really don’t like, so again it’s a risk. The last thing a writer needs is to give the impression they are showing off, when in fact they are trying to entertain the reader to the best of their ability in an offbeat way.

You describe yourself as a writer of “fantistika.” What does fantasy allow you to do that, say, Dickensian realism couldn’t do as well in illustrating human foibles?

Dickensian realism certainly does illustrate human foibles as well as any fantasy fiction can. Let’s be clearer and state that it probably does so with more pertinence and effectiveness. There are several reasons why I write mostly fantasy and only occasionally realism. One of those reasons is that the illustration of human foibles is something I am not very good at, and with fantasy I don’t need to excel at it. I know my limitations as well as my strengths, I hope, and there are so many brilliant writers who are so accomplished at launching investigations into life as it is lived on the ground by us all, that I feel it would be very unwise to try to compete with or emulate them. If I can contribute to literature as a whole, then it is going to be in a very small way that is also precise. Maybe I can push the boundaries of one small corner of one subset of literature, a corner in the fantasy realm. I specialise in concepts and the transformation of those concepts using a certain kind of logic.

What I mean by this is that my most original stories tend to employ the logic of word association or lateral shifts of images and ideas rather than empirical logic. They are thus not directly about the real world. But they exist in the real world, of course, and are part of it. Someone once said about Calvino that he holds up a mirror to the world and writes not about what the mirror shows but about the mirror itself. This isn’t quite true but it’s a nice quote and it does have some truth in it. I wouldn’t say I hold up any sort of mirror to anything, but maybe I put language in an echo chamber and write about the distortions? I’m not sure. It was once said of my work that I put a big red nose on language. That description pleases me too. I enjoy reading many kinds of fiction, including the most grounded forms of realism, but I don’t write as widely as I read. I write fantasy mainly, and comedic fantasy at that, sometimes philosophical comedic fantasy, and I content myself with admiring the great realists who can sink their teeth into the world.

As for Dickens, well he was often a comedian too, and a fantasy writer of sorts. I like Dickens a lot, but if I was going to settle down with a realist writer, I would be inclined to choose someone like Steinbeck, although we don’t have to read much Steinbeck before we realise with a pleasant shock that he too had a wide and deep streak of old-fashioned romanticism in him. His first novel, for example, was about the Welsh pirate Henry Morgan and his last was about King Arthur !

Other realists I love often write about real places that might seem unreal to me because of inevitable differences in geography and culture. This is when realism serves the functions of fantasy. Chinua Achebe, Cyprian Ekwensi, and George Lamming usually keep their feet on the ground, but that ground seems oddly refreshing to me because it is ground I have never walked on. In fact, as I get older, I wonder more and more about the differences between fantasy and realism and whether they are illusions. The London of Dickens can be as alien as the Mars of Ray Bradbury.

What do you look for in a good story and which authors do you find produce stories exemplifying those qualities?

I think that I most enjoy a balanced combination of the head and the heart in a story. Calvino, for me, is a supremely good example of a writer who can be both intellectual and empathic at the same time. His work might be rigorous and based on some mathematical constraint, but it might also be deeply emotional, resonant with wistfulness and nostalgia. Sometimes he manages to blend both kinds of writing together. Despite my love for the more complex types of writing that are based on logic or mathematics or some other formal system, we ultimately have to engage emotionally with a work. It’s true that a tricky cerebral problem and its ingenious solution can provide us with an emotional charge. I suspect this is why so many of us enjoy the more elaborate forms of crime fiction, but literature is even more powerful when we can tune in directly to the characters, situations, images and outcomes of a narrative.

I talk about Calvino a lot, and Borges, and Lem too, who wrote tales so original and delightful that they have etched themselves so deeply into my psychology I doubt I will ever forget them. But this kind of technical storytelling, which is often light-hearted as well as intellectual, isn’t the only kind I enjoy. It’s more a case of me talking more about mathematical based fiction than other kinds because I am more often asked questions on it. There are many writers I love who surely never gave a hoot for any kind of formal constraint. It’s good to have a wide taste when reading.

I have recently been reading a lot of Georges Simenon, utterly wonderful when it comes to atmosphere and evoking the past, with the background details so rich that they seem to occupy the forefront of the story, though in fact they are always incidental to the action. If I take a quick glance at my bookshelves I see books by Anthony Burgess, Mikhail Bulgakov, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Miguel Angel Asturias, Maithreyi Karnoor, Jack Vance , George Lamming, Kinky Friedman, Ronald Firbank, Boris Vian , Jim Dodge , Felipe Alfau, and many others, few of whom have thematic or stylistic connections with each other.

I’m aware I haven’t really given you an exact answer to the question and this is mainly because what I look for in a story is fairly nebulous. It is, as I have said, a case of balancing intellect with feeling, but it perhaps is also about language as much as ideas. I love lyrical language. One of my favourite contemporary authors, Mia Couto, appeals to me because of the melody of the books, a style so lyrical it becomes almost surreal, but retains its precise meaning. I think that I only have one rule, which is that a plain prose style is one that tends to appeal to me less than one that sings. But again, there are exceptions. A plain prose style might have no melody at all but it might be powerfully rhythmic. I don’t always expect to learn something new from the fiction I read, nor to find confirmed the things I already feel, but I do wish to be borne along on a musical wave of some kind, whether tuneful or percussive.

What other stories or books do you have coming out, and from which publishers?

I tend to have a lot of projects on the go at the same time. This has been the case for years. I have a big collection of tribute stories to authors I admire due out from Centipede Press in a very collectible deluxe edition soon. I say ‘soon’ but I have no idea if it will be next year, the year after, or the year after that, as the book has already been in preparation for a decade. But I know it will look great when it is finally ready. That book is called The Senile Pagodas. I have already mentioned my collection of experimental stories called Your Number’s Up. I will have to work on that in the new year. I also am in the middle of a series of linked crime stories that should form a novel when they are all done. That book will be called The Reconstruction Club. The first three stories in the series have been published in various anthologies but I think the sum will be greater than the parts because there will be lots of loose ends in some stories that are tied up in later stories, and the tying up of these loose ends will make new mysteries that also need to be solved.

I mentioned earlier that I leave realism to the experts and concentrate entirely on an offbeat whimsical fantasy. Now I am going to contradict myself and admit that I am also working on a set of linked realistic tales that should form another coherent novel when finished. It is about all the residents of an unconventional street and how their lives interact with each other. The title will probably be Mango Terrace. I do have other projects in mind, such as finishing two novels I began ages ago, one of which is a fairly straightforward fantasy picaresque called Unevensong and the other a long more literary romp called The Clown of the New Eternities. And I have a couple of novellas in mind that have been in mind for decades but still haven’t managed to find themselves on the page yet. So much work to do! I wish I was better organised, but I feel it’s too late now. Oh yes! And I have a collection of prose poems called Comfy Rascals due out from my Brazilian publisher, Raphus Press, next year. Or maybe the year after.

[A whole passel of Mr Hughes’s works may be found here.]

Three

Three

Ann Quin

And Other Stories

A middle-aged couple from the late 1960s, Leonard and Ruth, husband and wife, mull over their literally and figuratively sterile marriage after the apparent suicide of a recent house guest, a young woman, who also served as the couple’s emotional cipher, upon whom they privately projected their fantasies of a contemporary woman, alone and single, and what that might mean. It also reminds them of the child they’ve never had and the reasons for that.

S, as the house guest is referred to, left behind written and audio diaries, as well as some film footage, all done during her time with the couple. Separately and together Leonard and Ruth look through these documents, ostensibly to find clues to why S might have committed suicide. After a while, it becomes apparent to readers that they are trying to see how each of them was seen and understood by her, and if hints of infidelity (with S or others) could be found.

While S’s record remains ambiguous on the latter point, it roils within Leonard and Ruth the long pent-up resentments they have for each other. The resolution to those marital ills perhaps hints at why S might have committed suicide. An update perhaps, if any were needed, of Kate Chopin’s The Awakening.

Ennemonde

Ennemonde

Jean Giono (Bill Johnston, trans.)

Archipelago Books

Although originally published in France in 1968, set in France’s rural “High Country,” [INSERT 4b_France’s high country.jpg HERE] and beginning roughly World War I, much of Jean Giono’s Ennemonde sounds like present-day U.S.: a mash-up between Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County and the average Trump supporter.

“The tool that people around here have most often in their hand is a shotgun, whether it’s for hunting or for, let’s say, philosophical reflection; in either case, there’s no solution without a shot being fired. . . Monsieur Sartre would not be of much use here; a shotgun, on the other hand, comes in handy in many situations.”

“It’s not that these folks are worse than others; it’s that, individualists to an extreme and incurably solitary, they’re constantly afraid of being duped. And if love does that often (makes you a dupe), hatred never does; there you’re on solid ground. I love you: that’s never sure; proof is needed. I hate you: that’s solid as gold bullion.”

“The Protestants of these parts had since time immemorial protested against Protestantism. They’d ended up worshipping anything at all, so long as the anything at all demanded intolerance. Crown of thorns were consumed in every household, at every meal. Religion was a sort of commerce in which discomfort was always preferred to joy, scorn to pleasure, and ultimately vice to virtue.”

Violence, hatred, and discomfort are forces of nature entwined with nature—animal, vegetable, and weather-driven—red in claw and tooth and the ultimate arbiter of truth, unforgivingly so.

Ennemonde is the story’s titular heroine, a toothless obese woman (280 lbs.), honest but otherwise amoral. She struggles for and wins unstinting respect from the folks in her area, buying, selling, and raising sheep. Giono clearly respects and admires Ennemonde, too, for all her amorality. Her fight for respect in a male-dominated patriarchal world is not a feminist battle—Ennemonde would destroy any woman who stood in her way, as well. Giono’s argument is that anybody who wanted to achieve Ennemonde’s modicum of material comfort would have been required to do the same.

Ennedmonde’s way—nature’s way—is not to ostentatiously shove others aside. That sort of arrogance, coming from either men or women, will be met by the community with resistance and will be shortly put down, one way or the other. Instead, the way to success is through silence and cunning, as Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus would have it (exile is to be avoided). The High Country consists of subsistence-level shepherds, either with small families or living by themselves in one-room huts, hidden in dales beneath trees. Reputation matters more than money, and everybody knows each other’s business by what they hear, see, and smell in the wind. Revenge may take decades to arrive and appear in the form of the natural consequences of farm life.

In the second part of the book, an addendum of sorts, Giono seems to build a case for Ennemonde being a natural conclusion from the environment of the High Country, not a one-off. Thus, Ennemonde’s decisions to disrupt legal, ethical, and cultural traditions make sense in a world that never even pretended to uphold notions of Christian morality.

The Open Road

The Open Road

Jean Giono (Paul Eprile, trans.)

NYRB Classics

Taking place over the course of a year in rural France after World War II, The Open Road describes friendship and trust between an itinerant laborer and a con artist. Their trips from village to hamlet to town, by foot down roads and across fields and wood. Poverty is endemic to the region, and vehicles of any kind are still a luxury. It was off the grid before there was a grid to be off.

The narrator and his companion, whom he calls “the Artist,” roam from town to town, usually staying just long enough for the Artist to escape a severe beating for cheating at cards. The Narrator, on the other hand, is a trustworthy jack-of-all-trades whose preference is to stay in a town until the work runs out or he grows bored. And he keeps to himself, unlike the gregarious Artist. Although the Narrator’s gut tells him to keep his distance from the Artist, he still feels curious and compelled enough about the Artist’s fate to help him during tough times.

A picaresque novel, The Open Road illustrates France’s version of backwoods life—the simplicity and naivety, and the brutality of work, kinship, friendship, and hate. Giono is a master of reading nuance into human behavior, so even the meanest-spirited person possesses some semblance of empathy and decency. He illustrates social hierarchies, systems of obligation, and what passes for acceptable company. His characters know when the social norms can be bent and what the consequences will be if they snap. Paul Eprile’s translation is excellent, making Giono’s prose immediate and contemporary.

An interview with Paul Eprile,

An interview with Paul Eprile,

translator of The Open Road, Hill, and Melville, the latter whose translation garnered him the French-American Foundation’s 2018 Annual Translation Prize.

What drew you to Jean Giono’s works in general and The Open Road in particular?

His remarkable fusion of the sensual and the cerebral, his engagement with the natural world, the richness and strangeness of his language.

Giono’s works have unpleasant people in them, but he seems to effortlessly detect the humanity in them, despite their other (significant) flaws. If Giono’s people have a sense of god in the world, it is as a harsh, cruel, and final arbiter of truths. In The Open Road, the narrator seems to accept those terms while balancing them against his own interests. The Artist, on the other hand, seems more intent on deceiving the balance in his favor as long as possible. What about Giono’s outlook on life encouraged him to imbue a likability into characters who otherwise are dislikable? What makes his compassion for them believable rather than romanticized?

The Narrator and the Artist are complementary opposites, two halves of a whole. For the Narrator, who both seeks and shrinks from connection, the Artist is the ultimate challenge: remote, unforthcoming, habitually unpleasant. Both are ultimate risk-takers: The Narrator risks his heart; the Artist risks his skin. I think Giono recognized that all human beings embody these opposites, that our psyches contain them, and that different personalities negotiate and express them in different ways. He had witnessed human barbarity in its most extreme forms during WWI and became a fervent pacifist. So, while having his eyes wide open to the bestial, he strove for the angelic.

Giono does well in describing nature but it’s not a Thoreauvian view. How do you see, in Giono’s fiction, the interaction between humans and the flora, fauna, and weather of where they live? How does Giono try to understand humanity in relationship to nature?

Giono’s conception of the natural world is rooted in the identity of the mythical deity Pan. Pan was both an emblem of wildness and fecundity, and a sower of destruction. The natural and human environment in Haute Provence, Giono’s home country, was full of beauty and terror. As he describes it in Hill, the green, vegetal world is constantly threatening to overwhelm the cultivated, “civilized’ world, and the night is fraught with earthly and unearthly violence.

Giono’s conception of the natural world is rooted in the identity of the mythical deity Pan. Pan was both an emblem of wildness and fecundity, and a sower of destruction. The natural and human environment in Haute Provence, Giono’s home country, was full of beauty and terror. As he describes it in Hill, the green, vegetal world is constantly threatening to overwhelm the cultivated, “civilized’ world, and the night is fraught with earthly and unearthly violence.

Which of Giono’s works would you like to translate next, and why?

Eprile: I’m going to be rendering a little-known work, another one that’s never before been translated into English: Fragments d’un paradis. There’s great diversity in Giono’s oeuvre. This book is in part a sea tale, a genre I adore, and partly a meditation on the moral condition of Europe, in particular during the Second World War. It includes magnificent descriptions of marine and terrestrial life in the South Atlantic.

Which writers influenced Giono and which writers did Giono influence?

Giono’s great, early inspirations were the classical Greek and Roman authors. He adored Whitman’s poetry, Melville’s fiction and later, William Faulkner. In French, Stendhal and Balzac. In Italian, Machiavelli. For an autodidact, Giono’s erudition was vast. His personal library occupied a whole story of his house.

What other translations are you working on now and/or that will be translated soon?

I’m close to completing retranslations of two novels by Colette: Chéri and La fin de Chéri, for NYRB.

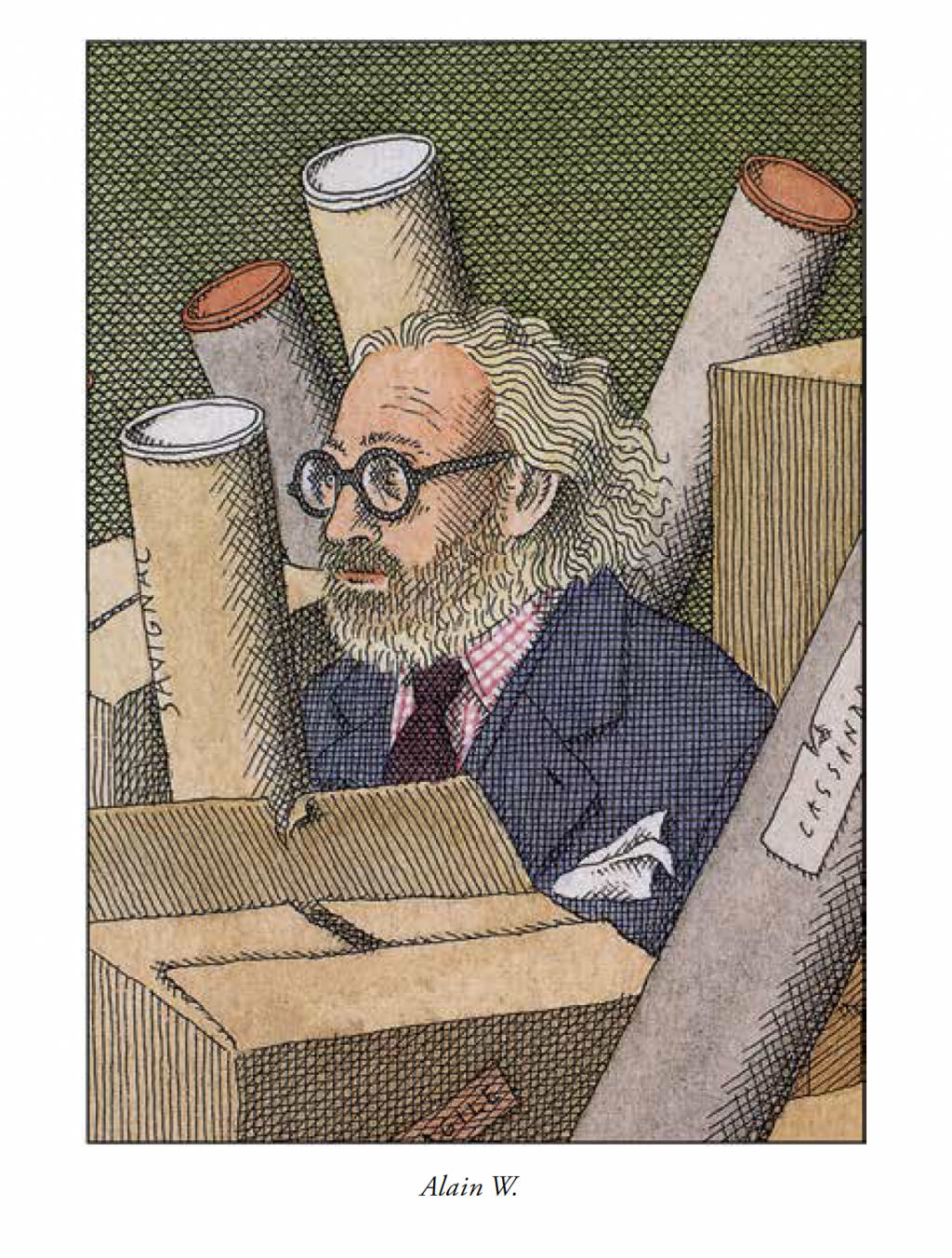

A Few Collectors

A Few Collectors

Pierre Le-Tan (Michael Z. Wise, trans.)

New Vessel Press

The illustrator and designer Pierre Le-Tan was a second-generation collector of fine art. Introduced to the world of refined taste by his father, a Vietnamese painter who eventually settled in Paris, where Le-Tan was raised, Le-Tan recollects even at the earliest ages preferring objects of aesthetic appeal over their ability to be played with, and kids usually do with the toys they usually want.

Verbal and pencil sketches by Le-Tan delineate some of the collectors he as befriended or traded with over the decades. Outside of the art world, probably none of these collectors would be known, in part for budgetary reasons and in another part for reasons entirely to do with taste, rather than investment value (which plays a secondary role—nobody here is stupid). They are recorded here, it seems, for their memorable tics and the types of things they collected—porcelain whatnots, death masks, dolls, urns, paintings, and sculptures. (The eclectic tastes give this book a roomy feel rather than of closing onto one genre.)

Verbal and pencil sketches by Le-Tan delineate some of the collectors he as befriended or traded with over the decades. Outside of the art world, probably none of these collectors would be known, in part for budgetary reasons and in another part for reasons entirely to do with taste, rather than investment value (which plays a secondary role—nobody here is stupid). They are recorded here, it seems, for their memorable tics and the types of things they collected—porcelain whatnots, death masks, dolls, urns, paintings, and sculptures. (The eclectic tastes give this book a roomy feel rather than of closing onto one genre.)

In addition to items of supreme craftsmanship, one person also collected crumpled paper, apparently delighting the play of light and shadows among the crumples. Another woman, royalty of no means of financial support, save the family’s painting collection, explains to Le-Pan as a boy what each painting was that is now represented only by the discolored wallpaper on the wall where it once hung.

It’s a charming bauble of a book, richly illustrated throughout by Le-Tan.

The Mill: A Cosmos

The Mill: A Cosmos

Bess Brenck Kalischer (W. C. Bamberger, trans.)

Wakefield Press

And now I ask you all: Has any one of you ever found a cadaver before the church doors on a winter morning? And read from its entrails?

I—I am searching for a cadaver before the church doors.

Originally published in Berlin in 1922 and appearing now in its first English translation, The Mill obliquely takes places in a sanitorium, ending with the narrator’s ostensible healing. (Kalischer herself died in 1933 of “the effects of ‘a nervous disease.’”) The book’s 26 unrelated sections have a surrealist feel, but I suspect surrealism wasn’t Kalischer’s intent behind her descriptions of events and creatures cosmic and quotidian.

Back in 1996, the psychologist Lauren Slater published Welcome to My Country [https://bookshop.org/books/welcome-to-my-country-a-therapist-s-memoir-of-madness/9780385487399], a collection of her observations and opinions of mentally impaired patients. Verbal communications by schizophrenics is the topic of the book’s title essay, where she posits interpreting schizophrenic speech as consisting largely of metaphorical descriptions of thoughts and feelings. Reading with this is mind doesn’t crack open the obscurity of many of the passages, but it does offer a way to understand the sections as mythical tales, remembered words of friends and sanitarium doctors and nurses, as aesthetic doctrines, and a mind still activated by the arts. Dream logic and dream-like images pervade and enrich the prose throughout, which becomes more coherent as the narrator approaches release from the sanitarium.

Exteriors

Exteriors

Annie Ernaux (Tanya Leslie, trans.)

Seven Stories Press

From 1985 to 1992, after she moved from the provinces to Cergy-Pontoise, a Paris suburb, Annie Ernaux kept a journal based on people she saw or met at stores and the subway, streets and parks. The journal served to document what she saw and heard and mull over her reactions to them to further understand herself, or at least the larger world of which she is a part. Here is a sample entry:

He got on at Achères-Ville—twenty, maybe twenty-five years old. He settles across two seats, his legs stretched out, sideways. From his pocket he extracts a pair of nail clippers and uses them, contemplating the beauty obtained after treating each finger, extending his hand in front of him. The passengers around him pretend not to notice. It seems to be the first time he has owned a pair of nail clippers. Insolently happy. Nobody can mar his happiness, the happiness of a man with—as the expressions of those around him suggest—bad manners.

Fans of Ernaux (such as myself) will enjoy this slim book, but readers fresh to Ernaux may want to start elsewhere among her works to appreciate why she is so well-regarded as a writer.

Blast Off

Blast Off

Linda C. Cain and Susan Rosenbaum, with illustrations by Leo and Diane Dillon

NYRB

A young girl, named Regina Williams, dreams of becoming an astronaut, exploring outer space (she has lots of schooling ahead of her!). Not dissuaded by her friends’ skeptical dismissal of her dreams, Regina builds a rocket ship from scraps of metal and other materials she finds among trash, and blasts off for outer space, where she encounters all types of cosmic wonders.

Of course, Regina represents the human imagination undeterred by obstacles. At least as important as that quality is the fact that this book, originally published in 1973, focuses on the imagination of a young Black girl—something never discussed in the book. The quiet, matter-of-fact normalization of Black girls with aspirations is probably the book’s most powerful affirmation.

Studies of Sihouettes

Studies of Sihouettes

Pierre Senges (Jacob Siefring, trans.)

Sublunary Editions

Pierre Senges writes books that play with genre, conventions, and prompts—not OULIPO-like constraints to work within but premises from which to begin. For instance, Senges’s Falstaff: Apotheosis is a tongue-in-cheek meditation on the significance of Falstaff’s feigned death in Henry IV, Part 1 (and requires no knowledge of the play to enjoy). He’s also provided Moby Dick with a sequel, Ahab (Sequels) (“the true aftermath of the adventures of Ahab”).

For Studies in Silhouettes, Senges takes false starts to stories found in Kafka’s notebooks, and writes his own story, parable, legend, speculation, etc. Some lines by Kafka are given multiple lines of development. Here’s a brief example (the words in bold are Kafka’s):

A team of horses escaped from their pen—it wasn’t an allegorical team of allegorical horses violently removed from the symbol of their isolation, but an actual panic of actual creatures set to alarms by shouts or by the first signs of an earthquake—but still, there were enough humans gathered round the pen to analyze the situation and to find meaning there.

Although well-established in France, where he’s published 15 novels, he seems to be slowly gathering deserved attention here. This is good introduction to his work, which joins erudition and wit in a way reminiscent of such writers as Italo Calvino, Enrique Vila-Matas, and César Aira.

Interview with Jacob Siefring

Interview with Jacob Siefring

MA, MLIS, an information professional and translator living in Ottawa, Canada. He is co-editor for Sublunary Editions’s Empyrean Series, dedicated to republishing works from the history of world literature. His translations of books by Pierre Senges include The Major Refutation, Geometry in the Dust, Studies of Silhouettes, and (as co-translator) Ahab (Sequels).

Pierre Senges’s works are intelligent, playful, and often funny, and yet he is often described as popular among “erudite” audiences. This might seem to imply that only a small readership gets the jokes. While the sources may be best known to an erudite readership, I don’t have the impression that understanding and enjoying his books requires familiarity with the original sources. What is hindering Senges from being as popular in the U.S. as other playful writers, such as Calvino, Vila-Matas, and Aira?

In twenty years, perhaps his name will be as well-known in the literary world as their names are now. (The work of Calvino, Aira, and Vila-Matas has been available to English readers for longer than Senges’s has, and they are older and further along in their careers, one should note.) I think his work is already known and respected, given the circumstances, and I don’t think anything is hindering Senges’s anglophone readership. As of this month, five of his books will be available for purchase and distribution in the United States, with another one (called Rabelais’s Doughnuts, a collection of 7 short writings, 128 pages) out in February from Sublunary Editions That’s about 1,500 pages of his work in English translation currently in print. This work has been supported exclusively by small presses.

What challenges for translation does Senges’s works pose—how much of his humor is based on word play and how much is story situational?

Senges is a master of the long baroque sentence—parenthetically self-interrupting, spiked with em dashes, hedging, the sense of a mind actively calculating, sometimes in slapstick style. Hardest to get right are often the many colloquial adverbial phrases, which I think of as the connective tissue through these complex sentences. I almost always try to choose the one that sounds most convincingly like what a not overly pretentious English speaker might say.

The humor is mostly situational: sometimes staked on the elaborateness of the book’s conceits, the irreverent treatment of historical figures, the startling incongruity of historical periods and concerns. Sure, there might be references to Kant but just after there is a reference to Buster Keaton. There’s a persistent effort to unsettle periodizations and to convey the shock of historical relativism. The absurdity of 13th-century soteriological debates considered from the vantage point of a 21st-century mindset, that kind of thing. Such juxtapositions can gobsmack and delight readers.

Hopefully, the tone walks a fine line between layman’s ratiocinations and a kind of virtuosity. Archaic ideas or objects, whether proper names (which vary in their standard forms between languages) or just old rare words (clyster)—these issues are solved quickly by online research. As for puns and wordplay, there’s not too much of that, but a little. There are few neologisms, portmanteaux, or contemporary slang, but I think most readers of Senges see pretty quickly that there is a freedom—an elasticity, you might say—in the syntax that can be quite idiosyncratic.

You’ve devoted a bit of time to Senges, translating Studies of Silhouettes, Geometry in the Dust, The Major Refutation, and the upcoming Ahab (Sequels). I’m assuming these are tasks of pleasure not duress. What do you find especially appealing about his works that you hope other readers will see, too?

Somewhere Mallarmé famously says that he learned English so he could read Edgar Allan Poe better. The way I started translating was sort of like that, as an experiment to see if I could reproduce one of Senges’s books in a way that I could read it with reduced difficulty and greater fidelity. I had translated some things before that, but not much. And then there was the length and the breadth of these books. I liked the audacity of Senges’s short books, those are the ones that I’m passionate about. This might be impolitic for me to say as one such book’s co-translator, but a 600-page novel is not really my jam. I like the books that are 100 or 200 pages long but that successfully turn the world upside down. Sometimes it can even be done in 50 pages. Trim Menippean satires. Or studies of silhouettes.

I should also say that the intertextual nature of Senges’s body of work is one of the things I like most about it, and that this is a quality of most of my favorite authors and books: the dream that, by reading one book, one might read all books at once. Senges’s books give their readers a road map that permits access to literally dozens of other exceptional works and authors that are fairly unknown. Or sometimes the references are canonical, but the treatment allows us to see these figures in a new way. He’s a “gateway author,” you could say.

Do you consult Senges with questions regarding your translations, and if so, which rhetorical issues are most important to him?

I do confer with him on ambiguous or difficult passages. I think my questions probably help him know that I engage closely with the text and don’t translate anything mindlessly. Translating mindlessly is far easier than one might think; good translators should catch that when they revise. Often there’s an adequate solution within immediate reach, but another one which is excellent can be arrived at through a moment of reflection. Likewise, being a translator can be a means to paranoid reading, by which one develops an instinct to second-guess every word of one’s draft, at whatever stage it is, like the harshest of editors, and to take full advantage of the English language’s unrivaled synonymy.

So far as I know, I don’t think Senges views any element or aspect of his writing as more important than another. I try to be as faithful to it as possible, at least as I am able to read it. Through his responses, and also from reading his essays, I have learned a lot.

Who have Senges’s influences been, and which authors do you see as influenced by Senges?

His foremost influences: Borges’s stories; the Italian fabulist logician Giorgio Manganelli; the Hungarian historical polymath Miklós Szentkuthy Manganelli for instance wrote The Parallel Book of Pinocchio. He also wrote Centuria: One Hundred Outoboric Novels (trans. Henry Martin, McPherson & Co, 2005, which is a really interesting book of 100 microfictions, wonderfully fabulist, by turns absurd, profound, light. A good handful of Szentkuthy’s books are available in English from Contra Mundum Press, and Prae II is probably being translated as we speak. Overall, Senges’s influences tend to be more from world literature than French literature per se.

As for the second question, I can’t really think of any authors, French or English, whose work shows the influence of Pierre Senges, unless it’s the scholars (Laurent Demanze, Audrey Camus, and a handful of others) who have recognized his work’s merits.

What other translations are you currently working on? Do you have a book you’ve only so far dreamt of translating?

Currently I’m not translating much, some poems, and very sporadically. There will be more translations in my future, but I must say, the relatively small size of the market for literary translations should be noted, and the disappointing nature of the pitching environment. The greatest problem in literary translation is funding and time; very few publishers willing to invest significantly in large projects that don’t have proven commercial appeal. (And in the case of works that do have proven commercial appeal, the publishers likely have a preferred translator already in mind for it—this is usually of no help to translators in the early- to mid-stages of their career.)

One project I’ve done a sample for and tried to pitch is Jean-Pierre Martinet’s Jérôme but I’ve given up on it. It’s a 500-page comically bleak novel, a monologue, for which the closest comparisons are Céline and Dostoyevsky. For a translator to be paid fairly for such a project would cost in the ballpark of $20,000. This is one reason to prefer shorter books. Otherwise, I hope to see Bruscambille and Charles-Albert Cingria slowly into translation.

My main occupations these days are working at the library part-time and editing books for Sublunary Editions’s Empyrean Series. We are republishing some of the greatest authors (many in translation) that you may never have heard of—Jean Paul, Boris Pilnyak, William Drummond, Kathleen Tankersley, Nicholas Breton, Emanuel Carnevali, Antonio de Guevara and more. The books are small, affordable, and elegant. I invite Book Beat readers to check it out. Like the books by Senges that I have translated, they are available for wholesale distribution to bookstores and libraries through Asterism Books, a new cooperative independent publishing distribution hub.

Books by Pierre Senges in English Translation The Major Refutation: English version of Refutatio major, attributed to Antonio de Guevara (1480–1545), trans. Jacob Siefring, Contra Mundum Press, 2016; Ahab (Sequels) trans. Jacob Siefring & Tegan Raleigh, Contra Mundum, 2021; Fragments of Lichtenberg, trans. Gregory Flanders, Dalkey Archive Press, 2017

Geometry in the Dust, illustrations by Patrice Killoffer, translated by Jacob Siefring, Inside the Castle, 2019, Studies of Silhouettes, trans. Jacob Siefring, Sublunary Editions, 2020, Rabelais’s Doughnuts, trans. Jacob Siefring, forthcoming from Sublunary Editions in Feb 2022.

Rationalism

Rationalism

Douglas Luman

Sublunary Editions

A literary exercise in “wanton misuse of the Google Translate API” via documents produced by Fascist-era Italian designers, who believed—typical of conservatives—in “architecture as the purest expression of state power.” Exposed by this manipulation is the violence towards others inherent, rather than ancillary, to fascist ideology in general and its rhetoric.

The night approves of violence & arrives

in chills & bruises. As if any Sunday

everyone arises to reenact their crimes &

spirits spend all their time dancing, lingering

until the last la di di.

Panthers and the Museum of Fire

Panthers and the Museum of Fire

Jen Craig

Zerogram Press

Jenny and Sarah—childhood friends from school who drifted apart after graduation—are opposites: Jenny is poor, a former anorexic working in radio, a non-writer always promising to to become a novelist; Sarah is wealthy, become morbidly obese while working a low-level council job, never breathing a word about writing but secretly completing a book before her death.

Only at Sarah’s funeral does Jenny find out about Sarah’s writing, when Sarah’s sister, Pamela, foists Sarah’s manuscript upon an unwilling Jenny. The manuscript—just the fact of its existence—is enough to encourage Jenny to review her life, her actions and inactions, her hypocrisies and alienation from others. Written as a breathless monologue much in the style of Thomas Bernhard, the book is about memories, memories of memories, and the ways in which memories are understood change over time.

Jenny is a person stuck in her own head, made too self-conscious about her own writing both because of the comments she and her one friend, Raf, make about writing done by others and because of her father, a man who has churned out thousands of pages during her life without ever feeling he has achieved the truth of what he wants to say.

Read metaphorically, the novel’s title (which is also the title of Sarah’s manuscript, based on a roadside sign outside of Sydney, Australia) could be rephrased as Ideas and the Imagination—and how Jenny learned to take the exit to see the attractions.

Papa Hamlet

Papa Hamlet

Arno Holz & Johannes Schlaf (James J. Conway, trans.)

Rixdorf Editions

Originally published in 1889 and now translated for the first time into English, Arno Holz and Johannes Schlaf’s Papa Hamlet introduced Naturalism to German literature. Naturalism, with its focus on recounting realistic tales in natural ways (“natural” here meaning “with the self-interruptions, digressions, pauses, mid-stream change of thoughts that attend actual speech”), paved the way for the Modernism that was soon to replace it and Realism as the leading schools of art.

The title novella Papa Hamlet and the stories that accompany it depict the squalor and hopelessness of impoverished tenement living—chronic unemployment, food insecurity, physical abuse of children and wives, mental illness, and alcoholism—with nary a shred of romanticism or hope for better. (These themes would later appear in the works of U.S. immigrant writing of the 1920s, such as Anzia Yezierska’s The Bread Givers.) The combination shocked Holz and Schlaf’s contemporaries, and even after over a century, the abuse depicted still appalls with its relevance. (Babies and toddlers die here because of neglect, beatings, illness, and starvation, all depicted as routine to the point of unsurprising to all but only mothers.)

James J. Conway provides an excellent Afterward that places Holz and Schlaf’s oeuvre within its literary and historical context, demonstrating how the authors’ techniques anticipated Modernist and Post-Modernism expression.

Berlin’s Third Sex

Berlin’s Third Sex

Magnus Hirschfeld (James J. Conway, trans.)

Rixdorf Editions

A fascinating and well-written document from 1904 about Berlin’s gay community and its relation to the larger culture around it. Magnus Hirfschfeld, who wrote this book, was himself gay and a practicing physician—and thus had first-hand access to all levels of Berlin society. Unusual for his time, I think, Hirschfeld believed that “uranians” (his preferred term for homosexuals) were born that way and thus should feel no shame or guilt for their feelings. Much of this book feels relevant today: stories of men and women abandoned by their families for being gay, blackmailing, lost jobs, and suicide. But he also describes Berlin’s gay culture as supportive, sympathetic, and at varying levels of self-acceptance.

Death

Death

Anna Croissant-Rust (James J. Conway, trans.)

Rixdorf Editions

Written over 100 years ago, Death is probably most notable less for its subject than a woman with seemingly morbid tendencies wrote it: 17 imaginings of final ends, some horrific, others blissful. Croissant-Rust matches morbid fascination to romantic anthropomorphizing, with results that are more often cloying than chilling. The prose poems also published in this volume, date from circa 1893, and the near constant emoting (back of wrist against forehead; fainting couch nearby) added to the mix significantly weakens one’s ability to stifle a yawn or eye-roll.

While Croissant-Rust’s writing hasn’t aged terribly well, her place in Munich’s literary scene of the will certainly be of interest for anybody filling in the gaps of their knowledge of the literary and artistic figures in German culture around the turn of the 19th/20th century.

Ghost Stories for Christmas

Ghost Stories for Christmas

Illustrated by Seth; Various authors

Bioblioasis

Long before Tim Burton foisted A Nightmare before Christmas upon the world (“at least the eighteenth century,” according to series “decorator” (his term) Seth)—telling and reading ghost stories during yuletide were popular activities among families throughout Britain and its (former) colonies, supported, during the Victorian Era, by magazines —as close to streaming media as the times allowed. Tim Burton, consciously or not, tapped into the enjoyment of the eerie on the eve of the holy, and the books in the Ghost Stories for Christmas series have as much to do with Christmas as Tim Burton’s film.

Since 2015, designer and illustrator Seth has provided “decorations” and republished, in conjunction with Biblioasis Books, 20 stories from the late 19th / to late 20th centuries. And for setting mood, Seth is master of shadows for effect. (I first noticed his use of shadows in his designs for the covers and end papers of the Peanuts reprint series from Fantagraphics.) Although the tradition of ghost stories at Christmas is largely forgotten now, the names of the authors selected are still remembered and read: Charles Dickens, Edith Wharton, E. F. Benson, Algernon Blackwood, Daphne du Maurier, M. R. James, and more. The books are small, measuring 4” x 6”, and short (generally 60 pages long, but Mrs. Oliphant’s The Open Door weighs in at 130—an outlier for the series to date). Seth’s design and illustrations are alone worth the price of admission, capturing and interpreting the mood of each story rather than necessarily illustrating particular moments.

That said, what are the stories themselves like? By today’s standards, few are scary, although most remain odd and creepy. R. Bridgeman’s The Morgan Trust puts a Welsh spin on tales of Shangri-La. F. Marion Crawford’s The Doll’s Ghost shows that not all cute dolls are filled with evil intent. M. R. James plays Punch and Judy while waiting for a dead body to turn up in The Story of a Disappearance and an Appearance, while Pulitzer Prize-winning and Nobel Prize-nominated Edith Wharton’s Mr. Jones investigates the whims of the eponymous stern and almost sadistic caretaker of a mansion long in Lady Jane Lynke’s family, now inherited by herself.

I find myself more satisfied by the longer tales—An Eddy on the Floor by Bernard Capes and The Open Door—perhaps because more length results in more mood-setting details and “evidence,” as it were, for the veracity of the tales. As with many ghost stories, these latter two stories reveal more about human treachery and kindness, respectively, than inhuman and ungodly Satanic forces. Treachery and kindness are at the heart of Tim Burton’s Nightmare before Christmas, too—battles without season but occurring during a time of hope.

Love Nest

Love Nest

Charles Burns

Cornélius

Is it a graphic novel, notes toward a graphic novel, or something else? For the past 40 years, Charles Burns has been honing his stark black-and-white images (and sometimes color, too) that combine Frank Capra’s “aw, shucks” midwestern naivete with David Lynch’s middle-class notions of cosmic turpitude.

The images (no dialogue) occur in sequences that sometimes suggest a storyline (many pages share in common a homunculus, either in or outside of a jar) and sometimes suggest merely a portfolio of portraits and tableaux. If you already like Burns (or Lynch), “sense” may be of less importance than being transfixed by the weirdness.