Batlava Lake

Batlava Lake

Adam Mars-Jones

Fitzcarraldo Editions

Barry Ashton is a civil engineer deployed to Kosovo with the British Army after the civil war there in the 1990s. He’s a bit of an ass—a dull-minded bureaucrat who imagines himself as rational, ticking off boxes on administrative forms, taking special pride in being “[q]ualified under the Safety Rules Procedures to inspect premises and equipment and to give the go-ahead for service personnel to undertake their duties.” A strictly-by-the-rules type as unimaginative and unreflective as you might expect—a casual bigot, indifferent to and/or confused by duties of marriage and fatherhood, a man of principle unless those principles put personal life at stake.

An unsurprising result of this set of traits is the disdain by which he is held by the army men forced to salute him and follow his orders, and by his wife back home who divorces him midway through his appointment in Kosovo. Oblique spoiler alert: Hints are dropped throughout the story about how well Barry performs his job, details I didn’t recognize were clues until the end, and then I thought of Raymond Carver’s story “So Much Water So Close to Home” (1981).

I’ve known and worked with people like Barry Ashton, people who valiantly attempt to become two-dimensional examples of humanity via a steady application of “rationality”—itself a concept too many people base upon wholly unexamined assumptions, allowing for evading personal responsibility. It is to Mars-Jones’s credit that he is able to restore Barry’s tragic third-dimension and by so doing highlight Barry’s significant moral failings.

Blank Forms Anthology 07: The Cowboy’s Dreams of Home

Blank Forms Anthology 07: The Cowboy’s Dreams of Home

Blank Forms Editions

Blank Forms Editions, a relatively new multi-media enterprise out of Brooklyn, publishes and curates numerous books, concerts, and recordings by and/or about a wide swath of avant-garde figures within the arts, with an emphasis on music interwoven with poetry and art. For those would recognize the comparisons, I’d say Blank Forms is to music what Cabinet and Esopus. have been to the visual arts

According to their website, “Blank Forms is a non-profit organization dedicated to supporting emerging and underrepresented artists working in a range of time-based and interdisciplinary art practices, including experimental music, performance, dance, and sound art. We aim to establish new frameworks to preserve, nurture, and present to broad audiences the work of historic and emerging artists. Blank Forms provides artists with curatorial support, residencies, commissions, and publications to help document, disseminate, and advance their practices.”

The anthology series upholds that mandate with, in this issue, interviews with song writer and artist Terry Allen, poet / performers Thulani Davis and Jessica Hagadoron, composer / performers Charles Curtis and Tashi Wada, a brief essay by René Duval (Louise Landes Levi, trans.), and more. Illustrated throughout with performance photographs and samples of the artists’ works. Many of the musicians also have or will soon have recordings available via Bandcamp. Some recordings were originally pressed in the ‘60s or ‘70s and have been out of print since; other recordings were made decades ago but never released before; and some are new.

In addition to including women and people of color in their mandate, Blank Forms also demonstrates that sites of innovation in the arts are not limited to New York City and Los Angeles but are spread out across the states, in small- to mid-sized cities.

Blank Forms doesn’t focus on any particular scene, school, or movement, save for those that blend rather than separate the arts and those that push and explore the boundaries and techniques of expression. I love the eclectic approach and the sense of artistic-historic continuity the artists represented by Blank Forms work within and expand. Highly recommended.

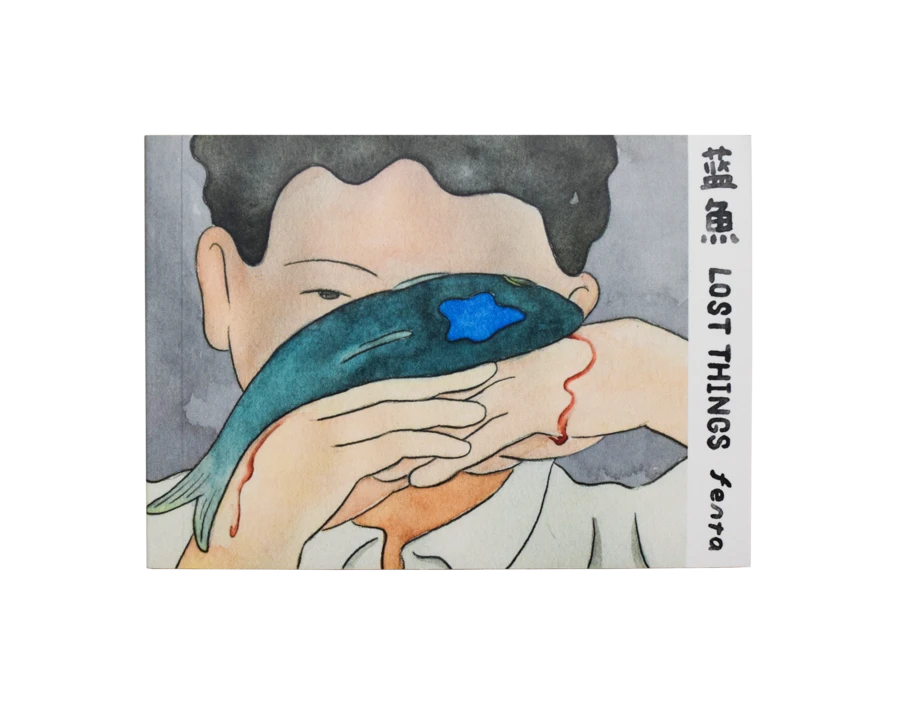

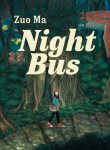

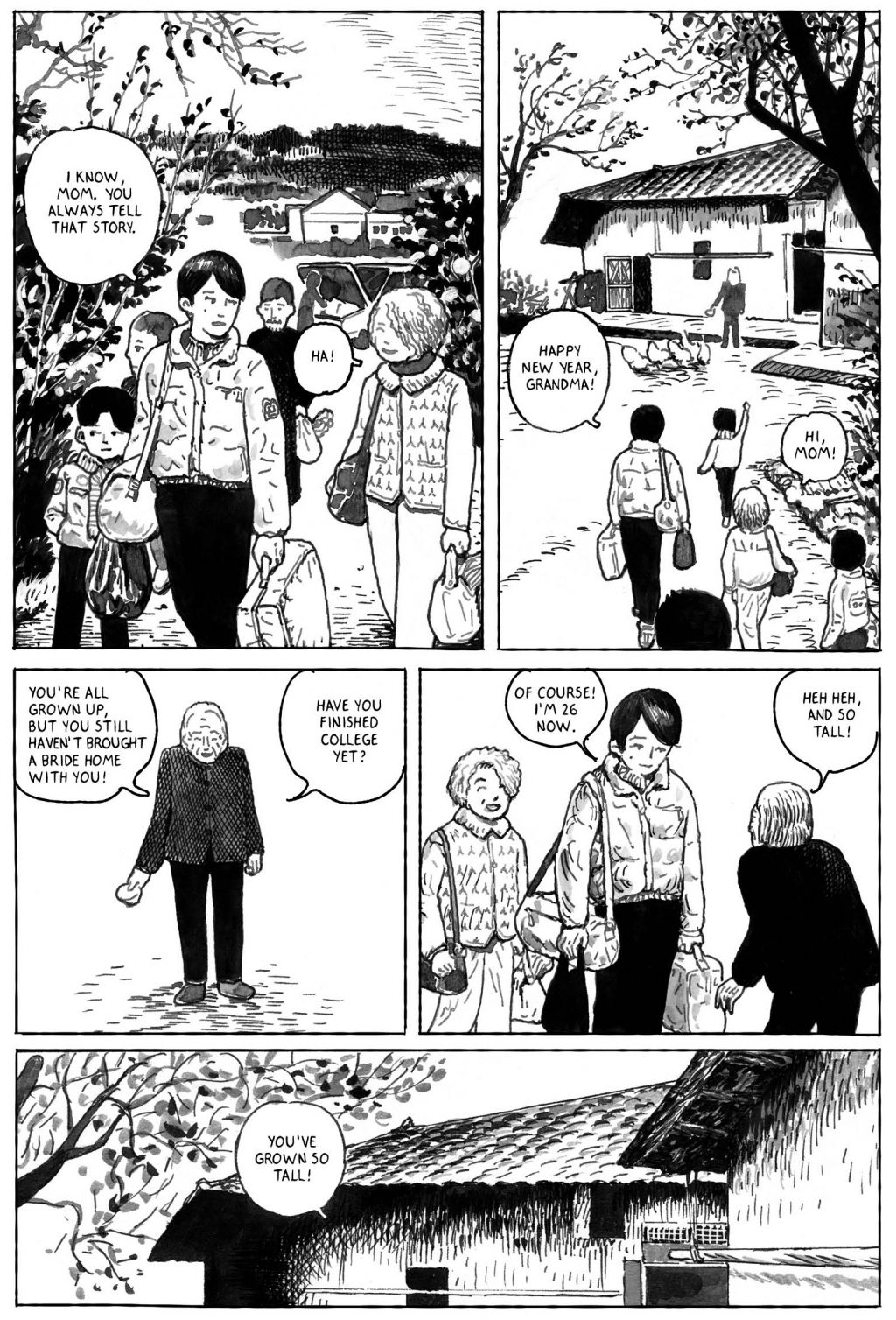

Night Bus

Night Bus

Zuo Ma (Orion Martin, trans.)

Drawn & Quarterly

Night Bus is a 400+-page anthology Zuo Ma, a cartoonist from mainland China, including the title story (a graphic novel-length work in itself), plus 10 stories, one of which in two versions.

Using “Night Bus” represent the issues and themes appearing in the other stories as well, Zuo illustrates and extolls rural expanses and forests as abundant with fascinating mysteries embodied as insects, animals, and plants. By contrast, cities are sterile and suffocating, unable to spark wonder and joy in life within the book’s narrators.

The narrators’ grandmother is also of key importance central in these stories. His elderly grandmother lives alone in material poverty the rural backcountry. Her unkempt house is part of a village undergoing demolition and dislocation to make way for industry. She has dementia, her eyesight is failing, but she can provide her grandson with rich natural surroundings, which become the touchstone for the rest of his life. His reminiscence of her is not mere sentimentality but also a recognition of the creative, life-affirming force the natural world imbues people with. Thus, the stories also act to critique rampant industrialization and the lives it destroys.

Interview with publisher, editor, and translator Orion Martin of Paradise Systems.

The book’s translator, Orion Martin, has been translating and publishing comics from around China under his Paradise Systems imprint. That a larger though still small indie press like Drawn & Quarterly is willing to introduce at least one of mainland China’s cartoonists to a larger North American audience is a good sign.

In addition to the title story, which could stand alone as a graphic novel, you also included several of Zuo Ma’s short stories, including two versions of one story. What about Zuo’s works encouraged you both to translate it and ensure that the book you put together would be big—a little over 400 pages?

We did have several discussions about how to structure the book and whether to publish it as two volumes, as it was published in China. The advantage of having all the material together is that it’s easier to see the many connections between the short stories and the longform work.

Zuo, as writer and artist, strikes me more as a naturalist than an urbanite. Nature, as represented in his work, is beautiful, mysterious, and rampant with fascinating insects, animals, and plants. The narrator of Night Bus turns to these elements when at a loss for story ideas. Does this assessment sound fair to you, and do others of Zuo’s generation express similar feelings about what is lost when cities and industries expand?

I think one of the major themes of Night Bus, particularly the short stories, is nostalgia for a landscape that no longer exists. Zuo Ma grew up during an era when the Chinese countryside was changing dramatically, and he has fond memories of exploring natural areas that have since been destroyed. I do think that it’s common for adults of his generation (Zuo Ma was born in 1983) to look more skeptically on China’s “economic miracle” and the unintended consequences it has had.

Apart from censorship issues, are there themes, techniques, or trends among Chinese cartoonists that make a cartoon Chinese, as opposed to American or French? What are the main censorship issues cartoonists face when publishing?

Underground cartoonists in China draw inspiration from many sources, ranging from manga to European and North American alternative comics, and their work is as diverse as their influences. I’m not able to make any broad claims about what is unique to Chinese comics, other than that they’re deeply interwoven with the social and cultural context of China.

In China it is difficult to independently publish a book. Most bookstores will not accept books unless they’ve been published by a mainstream publisher. For example, Zuo Ma’s graphic novel Night Bus is now being published by a large publisher, but the short story collection (which makes up the second half of the English edition of Night Bus) is still unavailable in most bookstores.

Which other cartoonists from mainland China do you think should be next in line for an English-speaking audience?

I can’t speak highly enough of the amazing cartoonists we’ve worked with at Paradise Systems. Some of these, like Yan Cong, Wang XX, and Xiang Yata also have large bodies of work that are largely unknown outside of China.

How did you discover lianhuanhua, and where in, say, Shanghai does a person find them? Does China have comic bookstores, as in the U.S.? I ask in part for selfish reasons: In the Shanghai bookstores I’ve gone to, I’ve only seen the usual Marvel and DC stuff, along with manga.

To find lianhuanhua in China, you’ll want to look in antique markets. There are a few independent bookstores in China, Wooden Bird (Beijing) and Bananafish Books (Shanghai) being the most important, where you can find contemporary independently published work.

Given the lianhuanhua titles you’ve already translated and published [link] plus your new introductory essay on the form [link], are you gearing up for a full-on anthology? Your work implicitly makes a strong argument for it.

To be clear, the books that Paradise Systems has published in a lianhuanhua format were not originally conceived of as lianhuanhua. Lianhuanhua are not generally considered part of comics history, either in China or abroad, but I personally believe that it’s an under-explored connection. By publishing works by contemporary Chinese cartoonists in a format that connects to vintage lianhuanhua, we were proposing a kind of continuity. But I think that the contemporary authors do not think of lianhuanhua as an important influence.

Which type of readers does lianhuanhua appeal to now? Given that lianhuanhua is not as popular as it once was, what in comics has replaced it in popularity, and does that shift threaten the future of this story-telling form?

Interest in lianhuanhua plummeted in the 1990s and has never really recovered. Many people who studied the history of the medium have pointed to the widespread availability of televisions starting in the late 1980s as a turning point. Lianhuanhua were a form of popular culture that became less relevant as new media became more widely available.

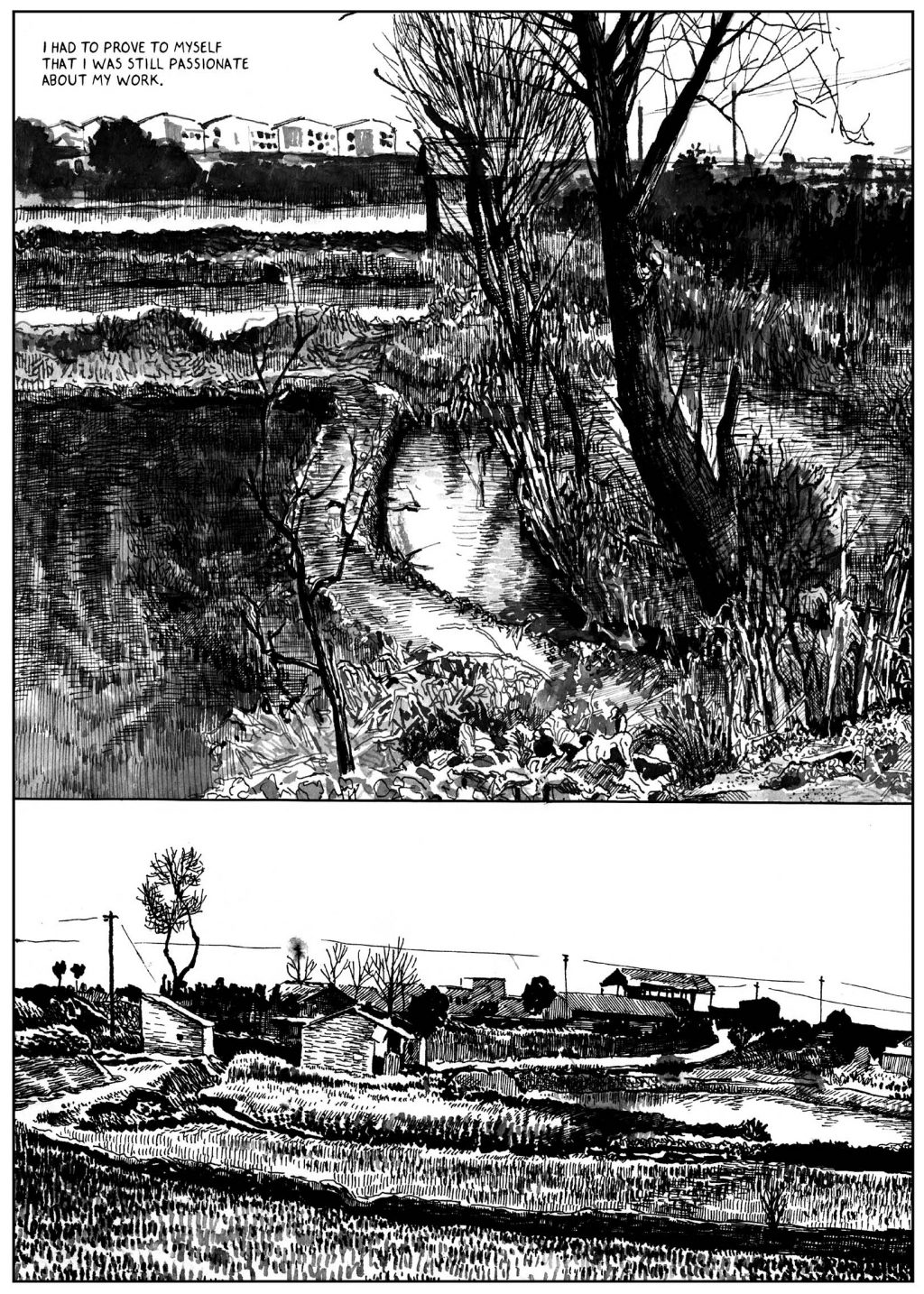

Lianhuanhua: China’s Pulp Comics

Lianhuanhua: China’s Pulp Comics

Orion Martin, editor and translator

Lianhuanhua are a form of comic books popular in China. Measuring about 3.5” x 7” and running from 32 to a hundred or so pages long, at the height of their popularity—1985—some individual titles had million-copy print runs, “with more than seven comics printed for each person in the country that year.” What publisher wouldn’t love to have numbers like that?

Topics covered by lianhuanhua are all over the place: From retellings of classics like Journey to the West to retellings of blockbusters like Star Wars, popular taste was catered to in ways common to other nations before they signed copyright-recognition agreements. China did not sign on to international copyright agreements until 1992; thus, a market for cheap entertainment was sustained.

And the rates of production almost defy hyperbole. Until now, I don’t think I have accused any writer I’ve read of understatement in their use of the adjective “extremely”: “Production schedules were extremely rushed, with turnarounds of less than 24 hours. After the release of a new film or theater production, illustrators and printers would work through the night so that they could sell lianhuanhua of the show outside the theater for less than the price of a ticket.”

Am I understanding correctly? Thirty-two well illustrated pages in under 24 hours? (At least the examples editor and translator Orion Martin shows here show signs of training and/or talent as draftsmen. Martin tells us that some lianhuanhua illustrators “were painters who found paid employment illustrating comics.”)

Anyhow, when lianhuanhua were first introduced during the 1920s in Shanghai, they appealed primarily to an audience that was 90% illiterate. Cheap enough for most workers (paying for reading time was an option too), lianhuanhua posed opportunities for both capitalists and communist propaganda machines. The result of that inherent contradiction in the system has been lianhuanhua’s turbulent existence between market-driven and party-driven demands. It still exists but its popularity has waned.

Lianhuanhua: China’s Pulp Comics is an introduction to an anthology that doesn’t now but should exist. For five examples and translations of lianhuanhua edited, translated, and published by Martin’s own Paradise Systems, check out this link: https://paradise-systems.com/products/lianhuanhua-bundle

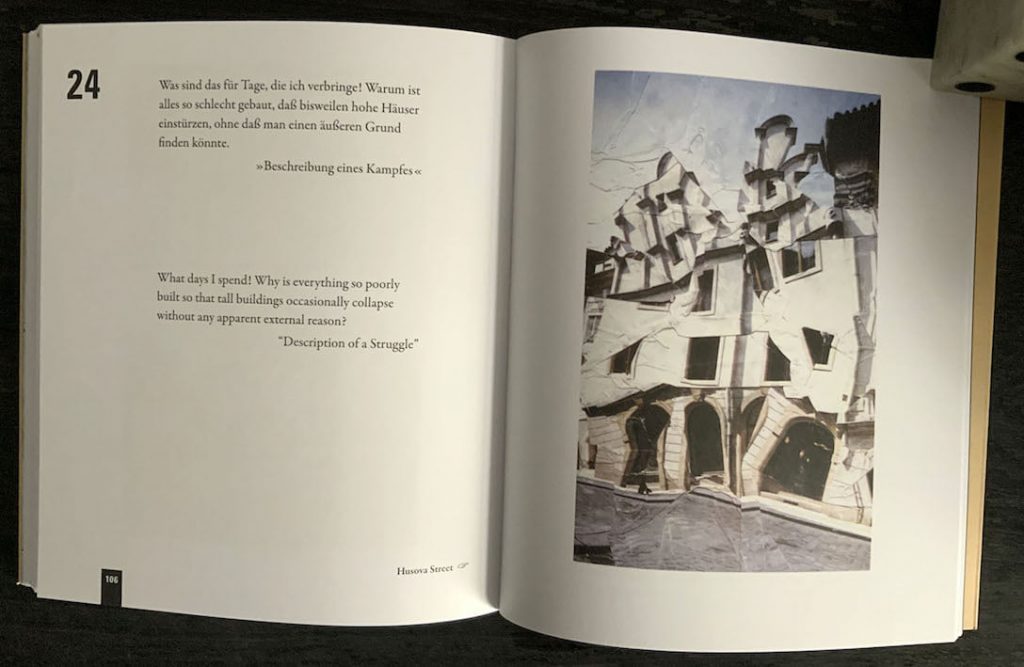

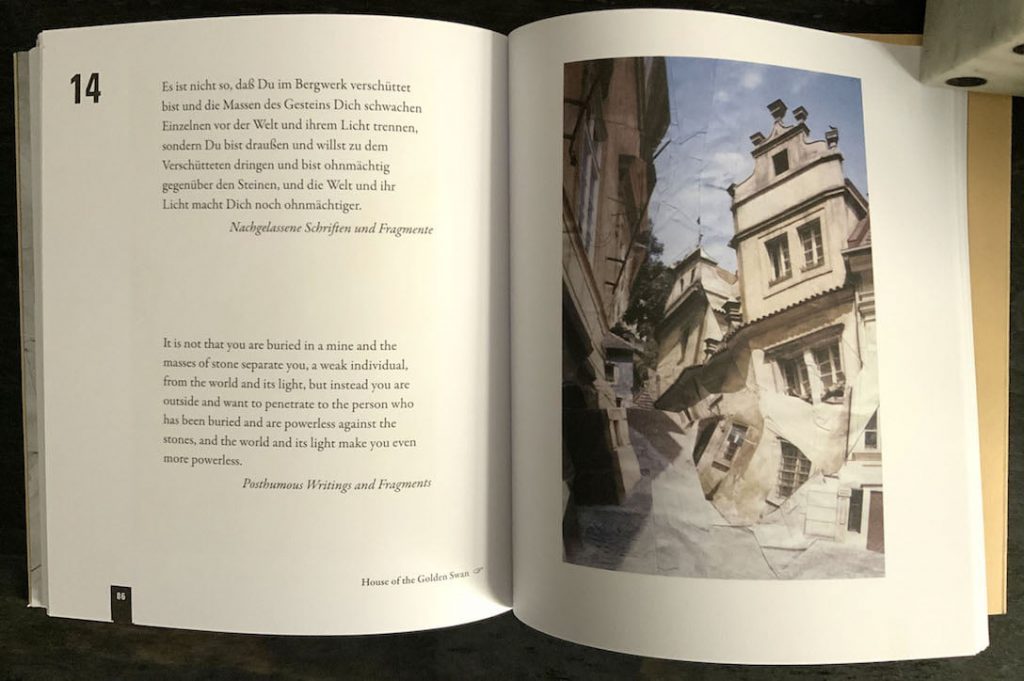

Responses • Kafka’s Prague

Responses • Kafka’s Prague

Jirí Kolá (Ryan Scott and Kevin Blahut, trans.)

Twisted Spoon Press

Jirí Kolá was a Czech writer and artist whose life (1914-2002) spanned most of the 20th century and included life under the thumb of, first, Nazis then, second, the Soviet Union. In practice, this meant that his work was banned from publication and thus circulated mostly under the table as samizdat (clandestine) literature. Responses • Kafka’s Prague brings together two works by Kolá, an essay (“Responses”) on how he arrived at a technique for producing images, called “crumplage,” and an opus (“Kafka’s Prague”) that combines quotes from Kafka along with altered images of the streets of buildings of Prague that Kafka would have been familiar with. Each work is lucidly translated by Ryan Scott (“Responses”) and Kevin Blahut (“Kafka’s Prague”).

In “Responses,” Kolá’s essay on art, poetry, and history, he notes that the best of the arts consciously places itself within the historic continuum and conversations within and among the arts: “Without a critical attitude, skepticism, and artistic prescience, without the burden of experience—I’m thinking here about those who came before me—nothing at all can be achieved.” In extending the techniques and topics of the past to match the contingencies and urgencies of the present Kolá felt as if neither images nor words by themselves was enough: “When you have a fateful encounter, you generally have to communicate in some way other than merely with words.”

Kolá? experimented with a number of techniques—some developed by others, some newly developed by him. One of those methods—“crumplage” (crumple + collage)—involved taking found images from books and newspapers and altering them. The impulse for this was beyond producing Dadaist or Surrealist pictures but was intended to convey senses of loss and beginnings:

Crumplage doesn’t work all that well with dry paper. It has to be properly moistened and the work done quickly. Crumpling must be done fast and carefully, and it’s difficult to predict results with this technique because it’s always the brother of chance. Because the moist paper is crumpled and the work has to be finished fast, hardly any adjusting can be done. Its meaning can be demonstrated on yourself, in that I think each one of us is burdened by countless moments when something has collapsed and we have to get on with our lives, even if reluctantly—don’t we all live with something broken inside? . . . [C]an we then say with any certainty that destruction doesn’t represent the beginning of something new?”

“My intention was to create something that should be more than read, so that what we call poetry could be felt. . . [T]he word wasn’t enough for me. I felt it were charged with an energy different from what had thus far been utilized.”

The following 60 pages or so make up the work “Kafka’s Prague” (1977-1978) to illustrate the broken and potential for new. One of my favorite lines from Kafka quoted in this work: “. . . as long as you do not stop climbing, the steps will not stop, they will grow upwards under your climbing feet.”

A tip of the hat to Twisted Spoon Press for publishing these works. Twisted Spoon was founded nearly 30 years ago in Prague by a group of ex-pats (if I recall right) dedicated to making available to English speakers writers from the Czech Republic and Central Europe unknown or underrepresented in English translations. My general rule of thumb is, if Twisted Spoon publishes it, it’ll be worth reading.

Let’s Not Talk Anymore

Let’s Not Talk Anymore

Weng Pixin

Drawn & Quarterly

The intertwined stories of five generations of young women (from great-grandmother to “imagined daughter”) depict crucial scenes from each one’s life at age 15. Spanning 1908 to 2032 (the imagined daughter) Weng Pixin (re)creates her matriarchal lineage, its gains and losses, its shared knowledge, and personal secrets. Over time, memories of shared experiences shift move further from shared understanding (subtly handled), further complicating their feelings for each other.

Weng also covers the changes from rural to urban living, in work and education expectations, and in degrees of autonomy for women. These changing contexts affect their options and obligations and raise tensions between the generations.

Weng’s style and color choices seem strongly influenced by Gauguin, which match the faux-naïf 15-year-old’s point of view. I like the stories she’s created, how she’s created them, their experiential reality. Overall, a lovely work.

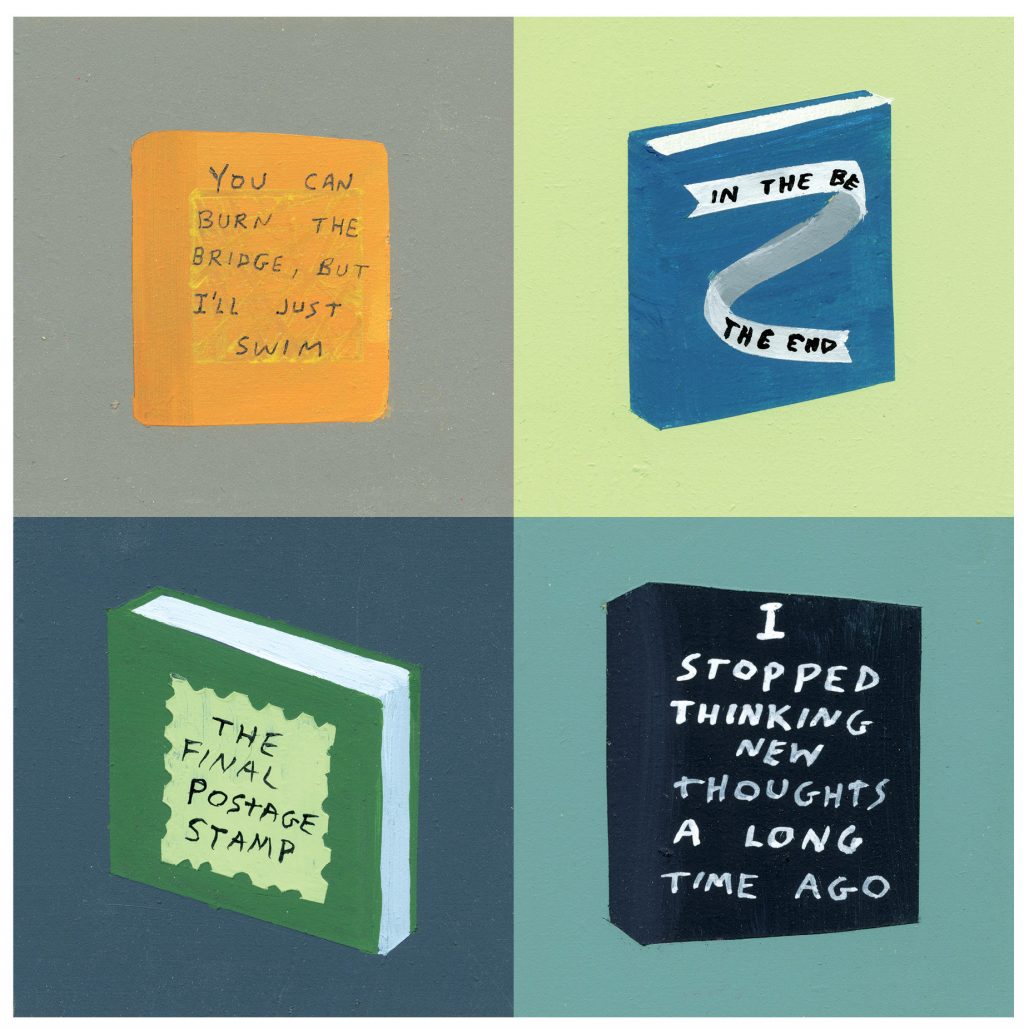

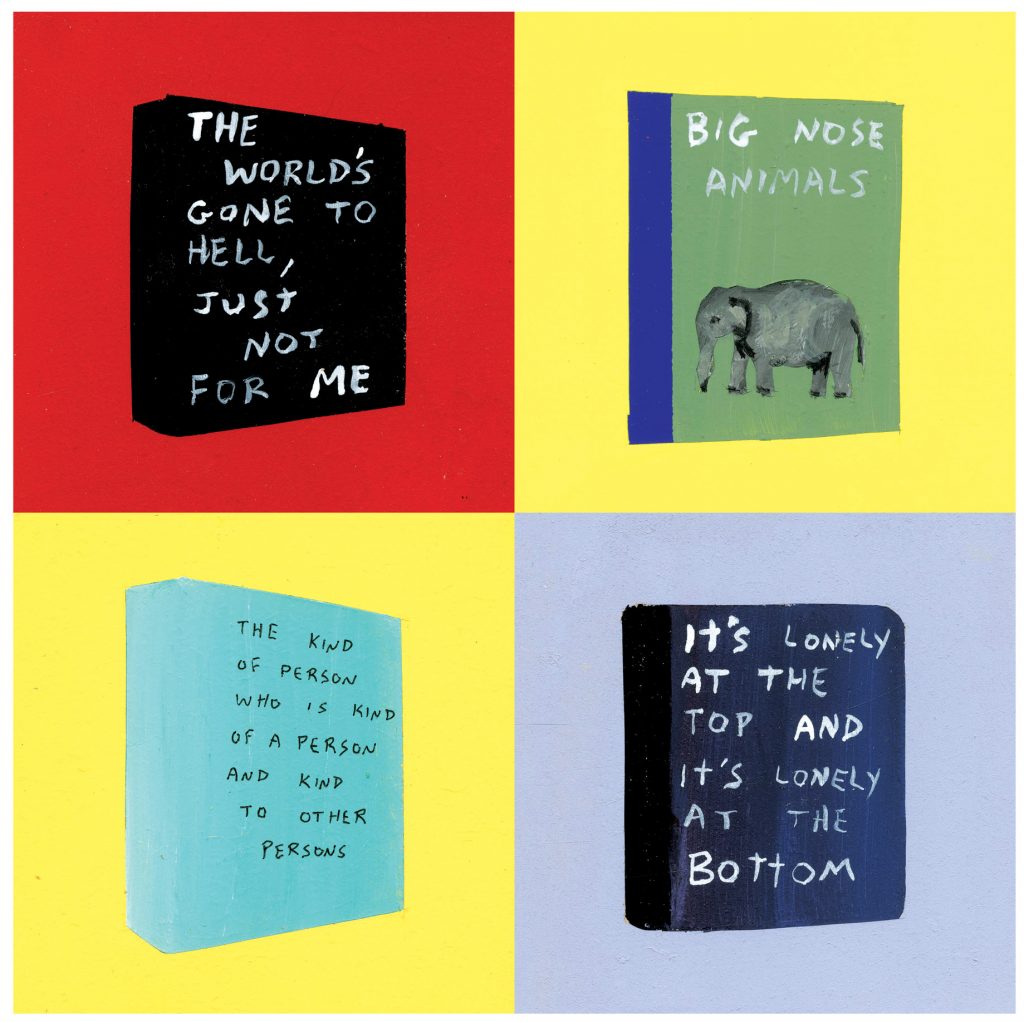

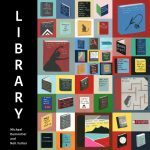

Library

Library

Michael Dumontier & Neil Farber

Drawn & Quarterly

Surely, every literate person has at some time, if not all the time, scanned over a bookrack promoting books deserving of more honest titles. A Boring Day of My Life in Fine Detail, say, or The Answer Is a Bunch of Science. Michael Dumontier and Neil Farber have performed a service for such literate persons by painting dusk jackets for books that do or should exist. Perhaps you have a taste for tough-guy fiction—may I suggest Dig Him Up, Let’s Kill Him Again or maybe My Way Is the Highway? The Rod McKuen-esque What Does Thunder Taste Like? and the non-apologetic apology I Said the Wrong Words, But I Pronounced Them Correctly both fit comfortably within this Library, along with a couple-hundred more. Browsing is encouraged.