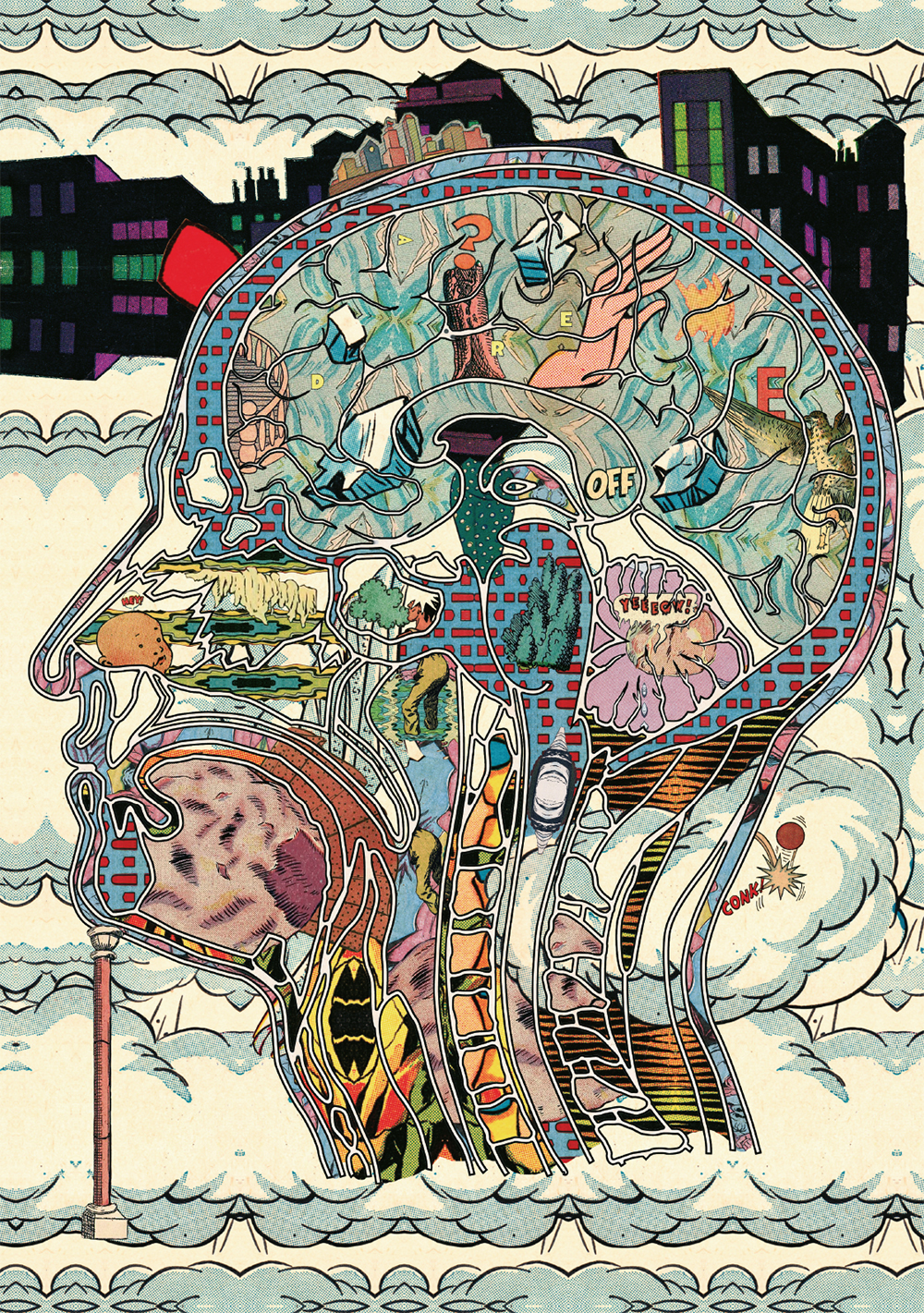

Anatomie Narrative

Anatomie Narrative

Samplerman

ION Edition

Images © ION / Samplerman

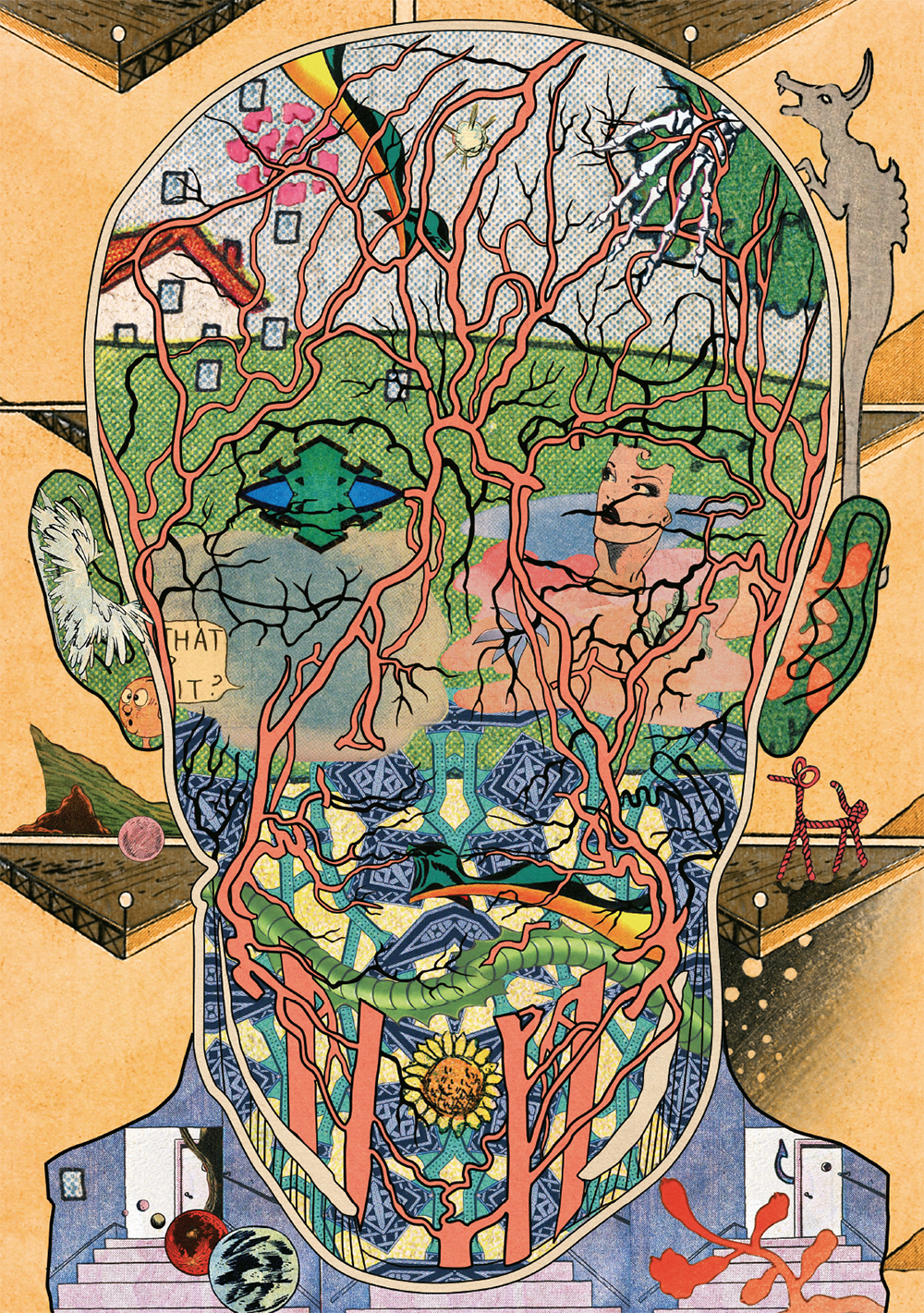

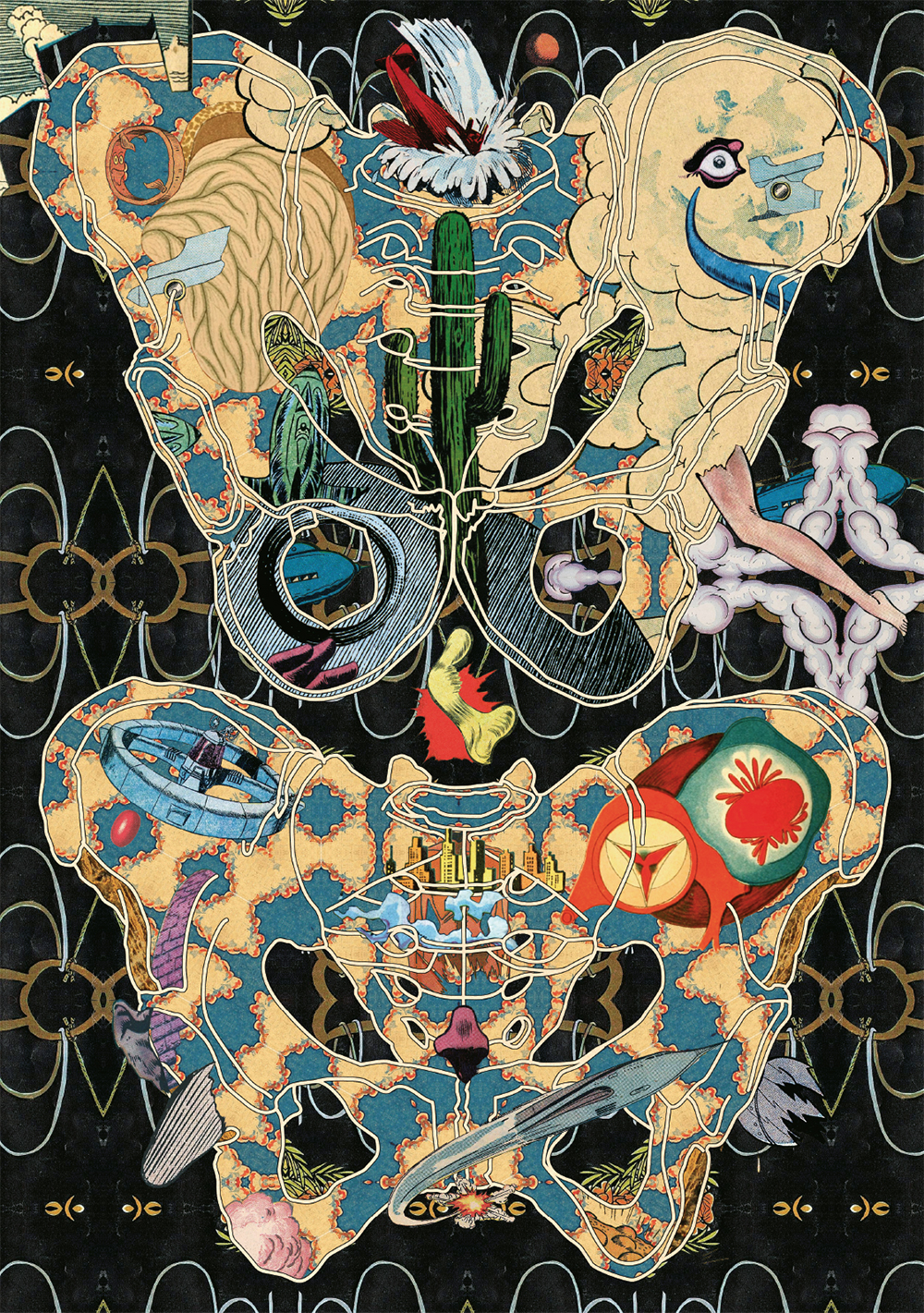

Samplerman (née Yvan Guillo) makes hyper-Pop Art eye candy based on fragmented and re-constituted comics art broken into almost fractal-like components, as if negative space must send him into anaphylactic shock. In his latest collection, Anatomie Narrative, Samplerman fills in the outlines of various portions of the human body. Symmetry and chaotic juxtaposition mesh into an overall single picture that compel viewers to stare and lose themselves in the patterns and motifs.

The images are energetic and crazy, and yet familiar, thanks to the source material. Like the principles of generative music—which may be based on a dozen or fewer simple phrases each of which repeats at different rates to the others—each piece is simultaneously familiar and unpredictable.

Q&A with Samplerman

What are your source materials, and how do you organize them? What qualities, for you, make an image ideal to repeat, splice, or otherwise alter?

I am digging into the public domain comics from the ’30s to the ’50s available on websites like the Digital Comics Museum and many others. My obsession with comics met the idea that was pushed by the founders of the Internet Archive around the first decade of this century that all this forgotten material digitized and available had to live again through art or any new creative way to display it.

I am slowly collecting the graphic elements I find interesting, organizing them by themes. What makes them interesting for me at first is their beauty. I discovered that making a composition of beautiful things put together can create something monstrous and beautiful at the same time. My other criterion for making a choice is just “I need a table a chair and a door” or [something] completely irrational.

How much of each page is planned out and how much is improvised once you have a basic idea?

I am trying to always change my process to keep it exciting and surprising. But most of the time I start with a template—this can be a comics page with empty panels or a geometrical shape or an anatomic board. The “content” of digitally cut-out scans of old printed comics and how they are displayed is never and cannot be planned out and is what brings life to the page.

I peruse through my growing collection of samples and select the ones that can fit; at the same time, I still look for new ones, so I go on downloading and looking at everything I can from what is available on the web.

I am making folders of “heads,” “furniture,” “cars,” “trees,” etc., so I can improvise while directing my collages toward certain themes, subjects, or moods.

Your new book is called Anatomie Narrative. I can see the anatomy, but am I missing a narrative? To me the images mesh symmetry and balanced color with (apparent) chaos. Is there really a story there or are you just enjoying the juxtapositions and the overall (literal) big picture you’re creating?

I sometimes struggle with the idea of telling something more or less approaching the shape of a story. Other times I leave it to the reader to decide if there is a story or not. The practice of collage brings a tension between the linear story I would like to tell and the multidirectional and elusive meaning due to the gathering of all these elements. Also, ION Editions, which publishes this book, are known for taking the less narrative works from artists who make more conventionally narrative comic books with other publishers. So, in that case I wasn’t feeling any constraint to telling a story.

Perhaps in the future I will be able to control the course (or the curse?) of the stories by making them more minimalistic and with the help of some meaningful texts and dialogues. In the [book’s] summary (in French) I tried mirroring the visuals in words by a collision—or a mix—of scientific, anatomic (more or less accurate) descriptions and often-used vocabulary from popular literature titles.

Your pictures seemed designed to give viewers much to look at—they open over time as one’s eyes acclimate to the details: they seem meant to be stared at and puzzled out. Is that an approach inspired by other cartoonists or artists who’ve influenced your style?

As much as I love comics, I have to admit in the case of my collage comics that I may have been more influenced by the music than the visual arts in my interest to rhythms and repetition (for example). Of course, I also love the psychedelics and surrealism that can be encountered in many comics from the ‘60s and ‘70s. I want to be graphically as generous as I can to [let viewers] drown inside my pages.

Principles of Cerebral Mechanics

Principles of Cerebral Mechanics

Charles Cros (Doug Skinner, trans.)

Wakefield Press

Charles Cros was a 19th-century scientist who, according to the book’s flyleaf, “drank with Verlaine,” “provided housing to Rimbaud,” and “invented the phonograph . . . and color photography.” (Although he was beaten to the patent on both accounts, the French still name their version of the Grammys after him). Thus, the Principles of Cerebral Mechanics is an earnest effort to reverse engineer, or theorize, the biological mechanics of perception. In 1872, when he wrote this paper, microscopes were not yet advanced enough to research the topic at the levels he theorizes upon.

What ensues is a logical argument, based on what was known at the time, that parses the various components of vision and assumes that all senses function according shared principles. In Cros’s estimation, the fundamental principles should be derivable from, say, the retina’s reception of color, to the input’s transformation of the color into information to be interpreted, to the body’s reaction (if any) to that interpretation.

Principles of Cerebral Mechanics serves readers today less as an example of a failed explanation than as a good explanation based on limited resources and rational-sounding assumptions that science later demonstrated false, in whole or part. Useful information may be garnered from negative results, although many people equate negative results as a competency-based failure. Why read something by an incompetent twit?

You read Cros because he was anything but incompetent. Isaac Newton practiced alchemy, a fact that many now find puzzling but no longer sneer at. Although Cros and Newton both turned out wrong about certain key phenomena, the larger point is that insights can be gained from bright persons’ mistakes—understanding where, why, and how they went wrong; which mistakes were preventable at the time; and which could be changed only via hindsight. If only others shared Cros’s own modesty towards personal error rather than moral revulsion:

I am either mistaken or I have seen rightly. Therefore, either my book will pass without consequence, and I shall have been nothing but a failure—not to be pitied, for I believed I was doing good—or it will open an unexpected path to knowledge and human power. [My emphasis—TB]

Q&A with translator Doug Skinner

This was the first work I’ve read by Cros. Once I read of his scientific achievements and his connections in the literary world, I wondered how I had never heard of or noticed him before. When I began looking around for more information about Cros, I quickly found that you’ve translated several works by him. How did you find out about him, and what about his works attracts you? What do you hope a new audience will discover in him?

In fact, I’ve translated only two other books by Cros: a collection of the comic monologues he wrote for the actor Coquelin Cadet, and a collection of stories written with the poet Émile Goudeau (plus some solo stories that are related). I think I first encountered Cros with Edward Gorey’s illustrated version of his verse “The Salt Herring,” and then with André Breton’s appreciation of him in the “Anthology of Black Humor.” I’ve also read a number of the writers affiliated with Le Chat Noir, and translated several books by the humorist Alphonse Allais, and Cros’s name keeps coming up. I like his imagination, originality, and high spirits, and his poetry is often surprising and affecting. His work remains popular in France (he’s even in the Pléiade), so I assume Anglophone readers will enjoy it too.

I’ve spent numerous years teaching engineering students the basics of writing and presenting technical information: characterize the problem, propose a method to solve the problem, state the results of implementing the method, and derive conclusions about how well the method solved the problem, from which revisions to refine the method could be proposed. I’ve also told them that valuable information can be gleaned from negative results. Cros’s essay embodies both, although the negative results weren’t discovered until later. What is Cros’s status in the sciences, and how does it compare to his reputation as a poet?

As a scientist, I think Cros is mostly remembered for his work on the phonograph. The French equivalent of the Recording Academy is even named the Académie Charles Cros in his memory. His work on color photography was dogged and extensive, but frustrated a number of backers by continuing to be promising but not good enough to be profitable; I think he’s admired for his historical importance in this field rather than for his accomplishments. He also developed an ambitious plan to seek out extraterrestrial life by sending giant light signals into space, which is recognized as being far ahead of its time. His poetry is probably more widely read, if only because more people read poetry than scientific papers.

How does a guy who spends his time inventing color photography and the phonograph ending up hanging out with Verlaine and Rimbaud? Can you see influences of poetry in Cros’s science or science in his poetry?

The 1880s and 1890s were exciting times in Paris, in both the arts and sciences. Cros’s two brothers were also polymaths, and led him into bohemian circles. His friend and champion Allais began his career as a pharmacist, and patented a formula for instant coffee, as well as helping Cros with some of his experiments. Cros’s poetry and fiction often do intersect with his scientific work. Both the phonograph (which he tellingly called the Paléophone) and the photograph were methods of preserving past impressions, of fixing memory, which is a theme that recurs in his poetry. He wrote some examples of early science fiction, too, including a romance between a man from Earth and a woman from Venus, and “La Science de l’amour,” in which a scientist has an affair with a woman in order to study sexuality.

Rummage through YouTube and you’ll find many adaptations of his poem “Le Hareng Saur” (The Salt Herring): as choral reading , animated cartoon, children’s book, song, modern dance, etc.

And Brigitte Bardot sings Cros’s “Sidonie”

Improvising: A one-year journey around Africa (16 Dec. 1995—16 Dec. 1996)

Improvising: A one-year journey around Africa (16 Dec. 1995—16 Dec. 1996)

Terrie Hessels and Emma Fischer

Terp Records

Published on the 25th anniversary of their trip around the west and east sides of Africa, Terrie Hessels (guitarist for The Ex) and Emma Fischer (painter) present their DIY document of the time, consisting of photographs, drawings, paintings, and diary entries made during their year-long sojourn.

From Morocco to Zambia, down to South Africa, then up Tanzania and Ethiopia—down, up, and through these and other countries, over barely-existent roads, sand, and non-OSHA compliant bridges, through forests and deserts, Hessels and Fischer—with a well-equipped Land Rover bought at auction from their native Danish government’s military—meet many happy, curious, and generous people on their trek, along with their occasional encounters with military personnel and government officials corrupt beyond socially tolerated grace.

Living primarily on beans, vegetables, and legumes (whether by choice or availability isn’t clear) and suffering from frequent bouts of diarrhea, the photographic evidence suggests a remarkably resilient and healthy-looking couple, despite the insects and tremendous physical labor sometimes required to manage the Rover down the road—clearing trees, shoveling sand or mud, etc.

Despite the many hardships, the trip was evidently worth it to the couple—which is good, considering that the entire venture seems to have largely been based on a whim (“travel is in Emma’s genes”), but a whim they spent a year preparing to enact, plotting their route, setting up travel dates and requirements for visas, determining fuel and water requirements, and quite a bit more.

The other item that confused me—and this is merely an issue of personal preference—is the fact that Hessels and Fischers’ trip largely consists of—as much as they can help it—driving straight along their map, without any intended long-term stays, rather than embedding for a month or so. But be that as it may, the sights, people, and food described here all sound interesting, and it’s the sort of rough traveling life that can make or break a couple. Over a dozen different African performers appearing on Hessels’ record label may be found here: https://terriehesselsterprecords.bandcamp.com/music

As interesting as Improving is, and understand that this is a DIY labor of love, a bigger budget could be spent on time to clarify descriptions that make less sense to us who weren’t there, captions to the photos for similar reasons, and better paper for the photos to be printed on.

I Wish

I Wish

Ingrid Godon (picture) and Toon Tellegen (words), David Colmer (trans.)

Elsewhere Editions

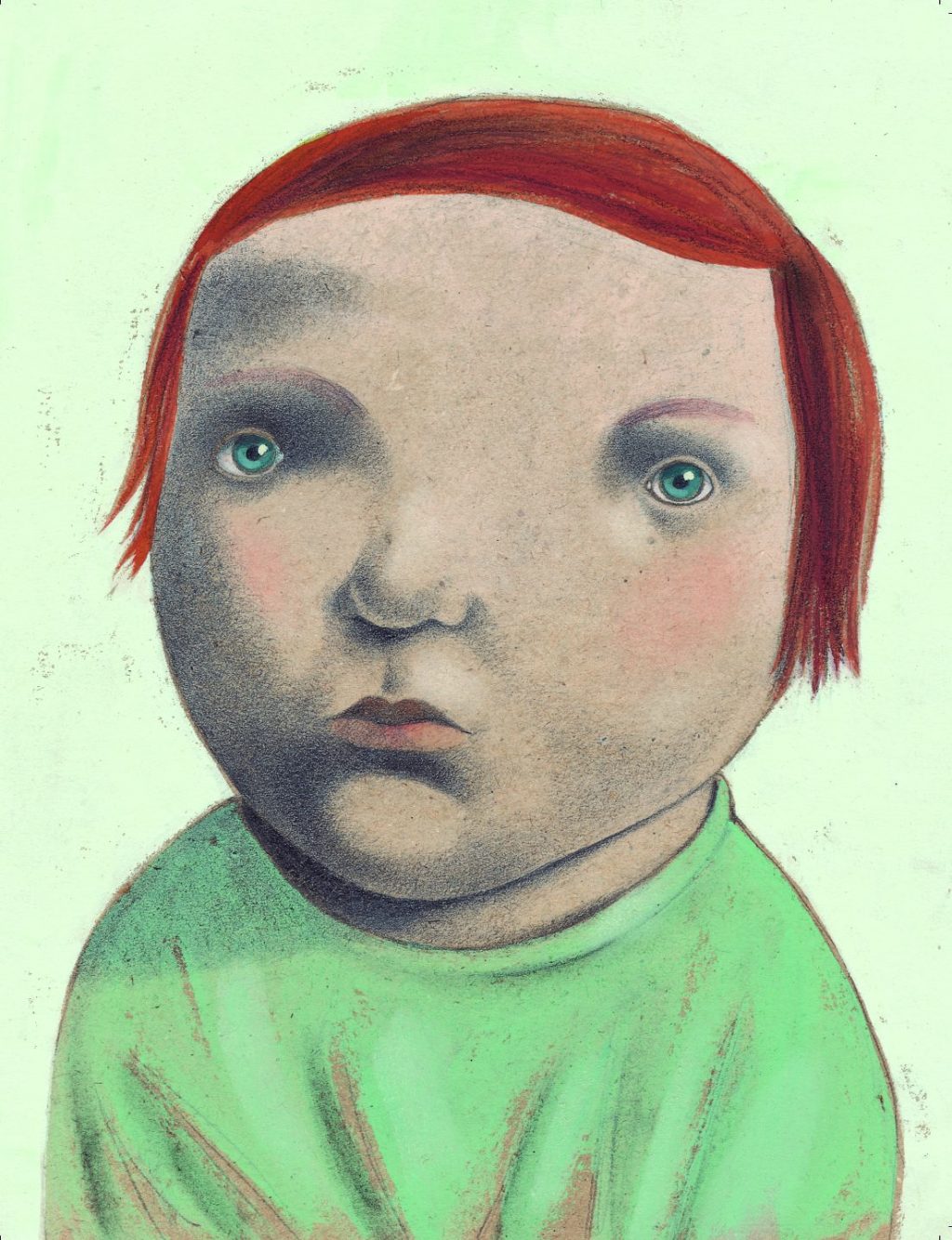

Ingrid Godon and Toon Tellegen have separately won many awards in their respective fields. For I Wish, Tellegen added brief thoughts for each of the characters depicted in a series of portraits by Tellegen. (It isn’t clear to me whether Tellegen or Godon named the portraits.) The match is excellent, and the pairings of text and image often devastate with their ingenuous simplicity, especially since most of the portraits seem to be of children, whose wide-set eyes and closed lips suggest mild unhappiness or befuddlement.

Almost every pairing begins with the words “I wish,” such as these, from “Susanne”:

Almost every pairing begins with the words “I wish,” such as these, from “Susanne”:

I wish I wasn’t scared of dying.

There are people who aren’t scared of death.

When they see him coming they just stand there

calmy and call out, “Hey, Death!

It’ so nice to see you!”

But those same people hide in the basement during

thunderstorms or scream and climb up on tables

when they see a mouse.

I like mice and thunderstorms.

Maybe everyone needs to be scared of something,

it doesn’t matter what, just like everyone needs

to breathe and eat and drink.

Otherwise you die.

And from “Carl”:

I wish happiness was a thing and I

found it somewhere and took it home with me

I wouldn’t tell anyone I’d found it.

I’d hide it and only get it out

when I was sure I was completely alone.

Then I’d buff it up.

Happiness needs to shine, even if it’s secret.

If I felt down and nothing I wanted was working out,

if everyone hated me and I was in the hospital with two

broken legs, boils, toothache, conjunctivitis,

chicken pox, and scarlet fever, I could tell

myself: but I still have my happiness,

it’s still there where I put it!

Each vignette represents a way of looking and understanding the world and one’s place in it—or being at a total loss to figure out what that place might be.

While I defer to the expertise of those who target the book to 8–12-year-olds, I suspect that I Wish is a type of book adults tell themselves they wish they had at that age for its examples of other kids who were dealing with the same doubts and hopes. But the likelihood is that when these same romanticizing adults were kids I Wish is exactly the type of book they would have ignored since its coolness is not immediately obvious. I Wish seems pitched to an emotional level I don’t recall myself having from 8-12, nor is it one I see among the few 8–12-year-olds I do encounter. Fourteen- to sixteen-year-olds, yes—but this isn’t a graphic novel or manga, so the kids interested in this book—for all its qualities—would likely be among the 10% whose emotional maturity is ahead of their peers. That said, I think adults rueful of their past will be those who appreciate this book most. If 8–12-year-olds would appreciate it, too, all the better!

You Can’t Be Too Careful

You Can’t Be Too Careful

Roger Mello (Daniel Hahn, trans.)

Elsewhere Editions

Roger Mello has illustrated and/or written over 100 titles for children and has won at least 14 awards for his works. The Möbius-strip narrative of You Can’t Be Too Careful, aimed at 5–8-year-olds, illustrates how the first half of the story came to be, then with a simple twist, repeats the story with opposite consequences for all the characters: the butterfly-effect forward and back, with hopeful transformation.

Mello’s illustrations prompt the eyes to look for subtle clues related to the narrative, and the calligraphy is gracious and whimsical. You Can’t Be Too Careful introduces to children the interconnectedness of actions and consequences throughout time and place, and illustrates how a simple, positive change in knowledge can lead to positive changes in action.

Savannah

Savannah

Jean Rolin (Max Welshinger, trans.)

Dalkey Archive

Jean Rolin, a French writer, was a close friend to Kate Barry, a British Vogue photographer, a generation younger than himself. In December 2013, she fell to her death from her fourth-story apartment. Given her years of battling depression and drug and alcohol problems, suicide was been assumed but never proven. Her problems with alcohol are only alluded to in his remembrance of a heated argument they had in 2007.

In 2014, Rolin decided to re-trace a trip to Savannah, Georgia he and Barry made seven years before, when Barry decided to make a film about the places the American writer Flannery O’Connor lived and visited during O’Connor’s life in Georgia. The challenge Rolin has set for himself in this act of memory and homage to his friend, Barry, is to be as doggedly faithful as possible to the exact route they followed and places they visited—despite his clear disdain for the latter in some instances. He has an aid in this: Barry incessantly filmed every place they went, including the plane flight. But the aid is limit: Barry had a predilection for filming feet. Thus, matching place in Barry’s film to the place they visited must sometimes be determined by reflections in mud puddles.

The parts of the first trip that were best were so in large part to the company over several days of their taxi driver, a man named Willy, whom Rolin has no luck finding again on his second trip. He does, fortunately for his mood, find another driver almost as good as Willy. “Almost” because Rolin has no knack or interest in small talk with strangers—unlike Barry, whose ease with strangers—no matter how sketchy—brought them experiences that enriched their trip.

Rolin’s curmudgeonly impatience with and disdain for all things small-town, chain-store America—prompts which only make his anger more resemble a prelude to a tantrum than principled reason scorned—all increase during his time in Flannery O’Connor’s hometown and visit to her peacock farm. The peacock farm was one of Barry’s reasons for the original trip, a fancy that Rolin—both trips—seems merely to tolerantly indulge. That said, his dedication to retrace their trip together remains earnest, and he forces himself to visit places that he otherwise finds repugnant, such as touristy pubs.

Has something been expiated, atoned for, or honored by the trip? Probably all of the above, depending on what we use our memories for.

In under two years—since late 2019—publisher Joshua Rothes’s Sublunary Editions has managed to go from “simply” publishing books in translation (about 8 a year) to—in January ‘21—adding a quarterly journal, Firmament (edited by Jessica Sequeira), also devoted to prose and poetry in translation (currently up to Issue 3). Now, with co-editor Jacob Siefring, Rothes has introduced the Empyrean Series as an imprint of Sublunary, which by the end of the year will amount to another 10 titles. I can only cheer on the ambition.

The mandate of the Empyrean Series—“dedicated to the reprinting, reintroduction, and revitalization of overlooked works from the historical catalog of world literature”—seems indiscernible to me from that of Sublunary and Firmament. Which is fine with me—I’ll leave it to Rothes, Sequeira, and Siefring to duke out the distinctions. As a selfish end-user, I only care about the results.

And the results so far are these: As with the Sublunary titles, the Empyrean Series focuses on short works ranging from 30 to 130 pages, with most under the 100-page mark. American, British, French, and Russian literatures are represented with works by Djuna Barnes, Laurence Sterne, Gertrude Stein, Thomas de Quincey, Boris Pilnyak, and others, writing poetry, fiction, and essays across the centuries—from Nicholas Breton’s Fantasticks (1577-1626) to Karl Kraus’s Poems (1930).

I’ve read and enjoyed five titles so far—Three Dreams by Jean Paul and Laurence Sterne (separately), Vagaries Malicieux by Djuna Barnes (the first piece by her that I finally understand), If You Had Three Husbands by Gertrude Stein (who continues to baffle me), Fantasticks by Nicholas Breton (a sort of Shepard’s Calendar, with page-long entries for the seasons, months of the years, and so on down to the hours of the day), and de Quincey’s The Death of Immanuel Kant—and have started a sixth, Jean Paul’s Maria Wutz.

Most books in this series (so far) can be read in an hour or so—ideal for a quick reading fix or for those interested in trying out world or avant-garde literature without having to commit a substantial time testing unfamiliar waters.

An Evocation of Matthias Stimmberg

An Evocation of Matthias Stimmberg

Alain-Paul Mallard (Sarah Pollack, trans.)

Wakefield Press

A miniature study in misanthropy á la Thomas Bernhard, purporting to be vignettes of memories by an Austrian writer named Matthais Stimmberg, who lived from 1901-1979. Stimmberg’s disgust with others in general and his own talents in particular manifested in apolitical silence, which in later life, post-WWII, cast suspicions upon his past. (That the printshop he was working in during the Allied occupation of Austria had copies both of Mein Kampf and a new book by Stimmberg probably didn’t help.)

Despite that, his circle of friends includes the poet and Holocaust survivor Paul Celan. In “Sisyphus,” Mallard has Stimmberg recount a time he owned a pet mouse that so captivated Celan, Celan immediately demanded to have the mouse for himself, along with its running wheel, to which Stimmberg had added an odometer to record the mouse’s distance each day.

Two months later, Celan returns to Stimmberg, empty-handed save for a handful of new poems he’s written:

[T]o my surprise, [the poetry] was about the mouse and his odometer. (Although, as often happens in Celan’s poetry, the wheel, and even the mouse, did not figure in the poem.)

I inquired after the mouse and the number of kilometers he had run so far. He confessed to having opened the cage door as soon as he left my house.

In “The Shadow and the Puddles,” Stimmung recalls about visiting a decrepit sanitarium in a town called Mannersdorf where he saw a man on his haunches “trying to pick his shadow up off the ground,” while fellow patients pissed on his head. The man then tried to use the urine to help him peel the shadow from the ground. This memory returns to Stimmung decades later when he returns to Mannersdorf to accept an award. At this point, the anecdote sounds like something from Bernhard:

I returned to Mannersdorf only around two years ago, to receive a prize. They have transformed the shell of the asylum into a sort of regional cultural center. . . In my speech, I talked about the shadow and the puddles. I suppose they regretted having award the prize to me. I, in any case, already regretted having accepted it.