Peach Blossom Paradise

Peach Blossom Paradise

Ge Fei [Canaan Morse, trans.]

NYRB Classics

“Let a thousand flowers bloom.” —Mao

Magpie brought the cicada to the pawnshop, but the pawnbroker wouldn’t take it. In fact, he wouldn’t even look at it twice. He stuffed his hands in his sleeves and said dully, “I know it’s gold. But gold isn’t worth anything when people are starving.”

“A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths are a statistic.” —Joseph Stalin

The hermit’s hedgerow is like the Peach Blossom Paradise:

After these flowers blossom, no others will bloom.

An old Chinese tale describes a remote spot stumbled upon by an outsider, who discovers a perfect place where all people and creatures are in harmony with each other, Peach Blossom Paradise. After his stay, he returns home, describing the paradise he discovered. Some dismiss his stories; others try but cannot again find the place described. Ge Fei weaves this tale with another search for Paradise on Earth, a pre-Maoist Communist Revolution that in part promises to liberate women from the tyranny of arranged marriages—so that any man can fuck any woman he wants at any time.

Xiumi, the novel’s protagonist, is around 12 years old when the book starts. Her father is a government functionary, and thus part of the upper class—an estate with land plowed by others and a house with live-in maids. He apparently goes mad, and just walks away from home one day, never to return. One doesn’t need to know about the violent tumult across China resulting from the late-19th century Hundred Days’ Reform to appreciate the shock and confusion among isolated rural communities far from any hub of reactionary or revolutionary turmoil about what is going on.

By age 15, Xiumi’s mother is almost out of money to run the household and sells her daughter into an arranged marriage. En route to her fiancé’s estate for the marriage, Xiumi is kidnapped and taken to an island while awaiting ransom. But neither Xiumi’s mother nor her fiancé is willing to pay her ransom, and thus the kidnappers rape and sell her off to another man. Passed among government officials and criminal kingpins, Xiumi learns ruthlessness and gains revenge. Perhaps worse, she also gains an ideology. Talk of revolution permeates the air, but when the characters in this novel ask each other what “revolution” means, the only working definition that they can guess at is “the ability to do whatever I want.”

While I was reading Xiumi’s transformation into a nightmare, and understanding the forces that shaped her, I came across a review of Alex Kotlowitz’s An American Summer: Love and Death in Chicago in “How Can We Stop Gun Violence?” by Francesca Mari, that focused on Kotlowitz’s descriptions of a young man, Thomas, with post-traumatic stress disorder brought on by the many murders Thomas had witnessed since he was 11 years old—friends, family, strangers. He is in a constant state of high-tension anger and anxiety. The only thing that quells it is violent release, which allows him to finally sleep.

Xiumi’s ideological vengeance—her violent release—ends with the death of her six-year-old son, whom she had never even bothered to name, consumed as she was by her revolutionary furor. The last quarter of the book regards Xiumi’s atonement and repentance, largely by heeding Voltaire’s advice to tend her own garden. A sense of redemption and grace concludes the book.

Ge Fei is an excellent writer, with a talent for empathy, depth, and subtlety. This is only the second book by him recently translated into English, and it’s the best novel I’ve read so far this year. Translator Canaan Morse has a keen eye for key words and phrases deployed and developed throughout the novel, echoing its themes: the dangers of ideologies, the fact that ideologies are rarely women-friendly (even in the hands of women), and the need and ability to recover from ideological delusions—“recovery” including humility and selflessness.

The Invisibility Cloak

The Invisibility Cloak

Ge Fei [Canaan Morse, trans.]

NYRB Classics

On the other side of serious historical fiction is light-hearted contemporary fiction, each skewering hypocrisies in its own way. Ge Fei, a professor of literature at Tsinghua University in Beijing, takes on (in part) capitalism at the nexus of government, commerce, and crime through the eyes of the narrator, Cui, who builds high-end stereo systems for high-end clients with no taste in music, an underlying frustration for Cui.

Although his clients are wealthy, Cui is generally poor since he spends his money on high-end equipment, most of which he never uses because his apartment lacks ideal listening acoustics. As the book starts, his sister tells him he must move out (the apartment is owned by her and her husband). Challenged to raise enough money to buy a new apartment, the narrator’s lifelong friend gives him the phone number of a mysterious man who wants “the best sound system in the world.”

The other subplot of The Invisibility Cloak is a search for a wife—most insistently on his sister’s part, far less so on Cui’s, who cannot image a replacement for his beloved Yufen, who divorced him.

What he needs, as his mother would put it, is a woman with “hatch marks.”

Factory Summers

Factory Summers

Guy Delisle [Helge Dasher and Rob Aspinall, trans.]

Drawn & Quarterly

Aah, the rite of summer jobs, when school is still a part of one’s life and the onset of adulthood looms ever closer. For many teens, it’s an introduction to the weird world of adults (apart from one’s family), whose occasional (or nonstop) pettiness has an authority ominously different from that suffered under among peers or parents: the friendly, overly-touchy mentor; the resentful coworkers (having to work only summers is a privilege).

In Guy Delisle’s newest graphic memoir, he details three summers he spent working in a paper mill in Montréal, starting at age 16. The son of one of the plant’s engineers, Delisle gets the gig easily enough, and immediately is challenged by the physicality of the work required during the four 12-hour shifts that make up a work week. The heat, noise, and danger contribute to the draining efforts required of the work, which includes monitoring and trouble-shooting multi-ton rollers that produce newspaper.

It’s an all-male environment (mono-cultural, too, it seems), where preening and posturing and physical and emotional toughness are prized. Delisle is just a kid, working a summer job, so most of the guys leave him be, letting him spend his downtime reading. (Reading is OK—this is Canada, after all—but weeping when Lennie is killed in Of Mice and Men is not.)

He develops acquaintances among the workers over the years, sees the stockpile of wood for pulp diminish each year as use of recycled paper increases, sees his father at work, and uses his factory wages to pay for his art school and his factory time to motivate him to never work in a factory again.

Watch: At Home with Guy Delisle

Echoes Shades

Echoes Shades

Piotr Zbierski

Charcoal Press

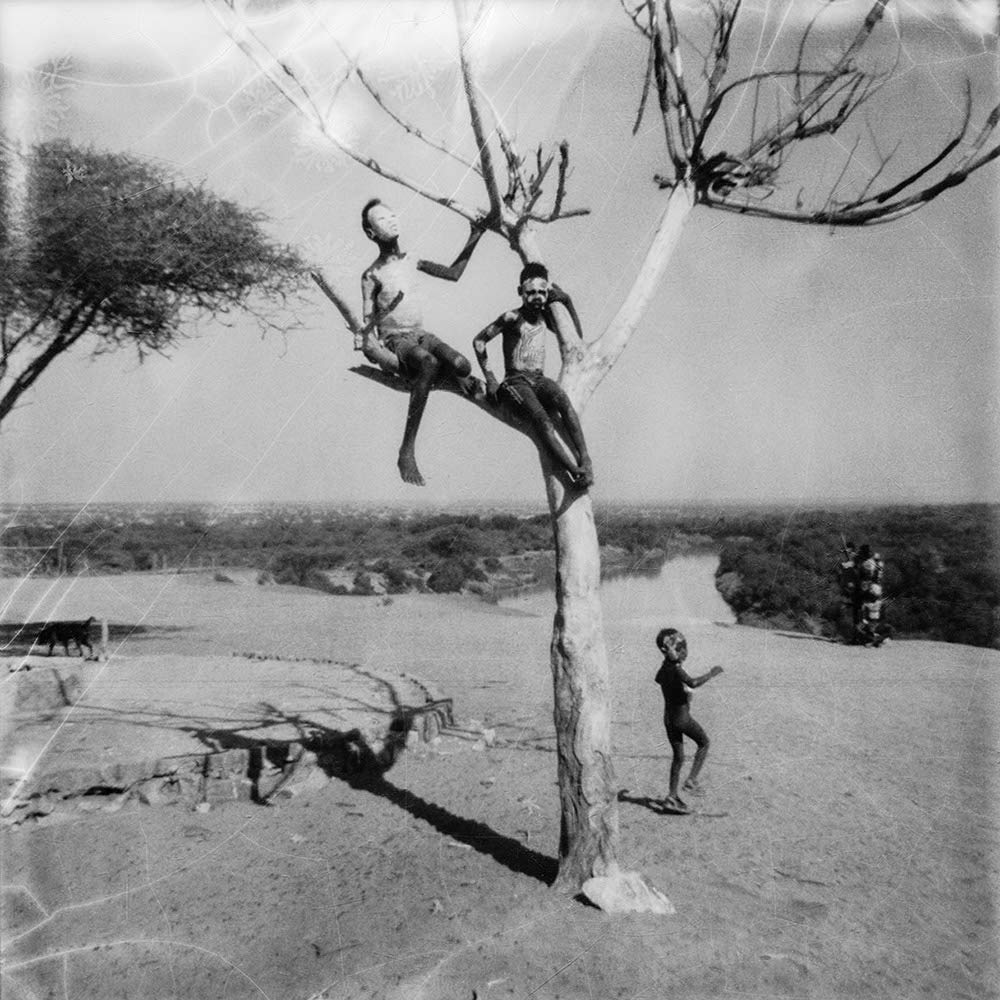

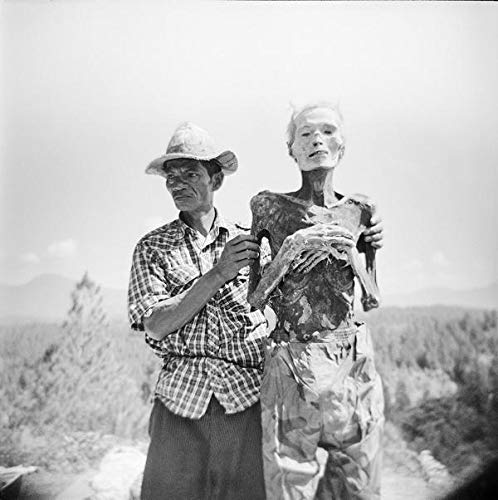

“I understand culture as an echo of nature, while its symbols, signs, products and rituals as shades of elements and phenomena that occur in nature.” — Piotr Zbierski

Photographing cultures in places as varied as Indonesia, Siberia, Africa, and Romania, Zbierski examines lives near nature—traditional, oral cultures whose members live at subsistence level. This near to nature means death is close by too, as whimsical as it is final. Ritual and spirit worship give cohesion to death’s arbitrary but inevitable appearance. Zbierski’s black and white photographs capture some of the energy motivating these lives, from simple point-and-shoot documentation to disorienting presentations of the ordinary, each shot a synecdoche of the broader community and its harmonies.

Permafrost

Permafrost

Eva Baltasar [Julia Sanches, trans.]

And Other Stories

Getting a job after someone’s put in a good word for you must be the closest thing to falling in love. You settle into a weightlessness that is for a while deeply pleasing, as though your life’s been whisked down a tree-lined promenade that crests at a bridge over still water. As you gaze at green mallards and their single-parent families, you let go. It’s so painless at the end of the day. And there’s so much beauty, born again in your own face, permeating the friendly halves of other people. Your senses are honed. You rediscover the sun, whose light shines all around you and falls over exteriors like geometric shapes at rest. I don’t see how this state of being can be normal. If it were I might not be so shocked by everyone’s eagerness to go on living day after day.

The lesbian narrator of this wry novel accepts her sexual desires but not the heteronormative social norms that paired relationships tend to imply for her—marriage, children, a home. Or, perhaps not “heteronormative social norms” but “controlling mom norms”: “One summer, we couldn’t go away on vacation because your university fees went up.” “The summer we couldn’t go on holiday because you needed braces.” “I still remember that summer when we couldn’t get away because your glasses broke and you needed a new pair.” “And what about that summer when we didn’t move house so that you could take a two-week intensive tennis course?” Et cetera.

As a result, the narrator is horny but cold to intimate trust, intelligent but directionless, open to new experience but prone to suicide. If the first three-quarters of the book could be said to be the case for her life’s uselessness—and thus her icy indifference to much of it—the last quarter of it is her reaction to having her bluff called.

“Families huddle like villages under siege. But the savagery that stalks and besieges us—is life.”

Can the Monster Speak?

Can the Monster Speak?

Paul B. Preciado

Semiotext(e)

[G]ender transition . . . entails activating those genes whose expression had been thwarted by the presence of oestrogens, by connecting them via testosterone and triggering a parallel evolution of my own life, by giving free expression to the phenotype that would otherwise have remained silent. To be trans, one must accept the triumphant irruption of another future in oneself, in every cell of one’s body. To transition comes down to understanding that the cultural codes of masculinity and femininity are anecdotal compared to the infinite variety of modalities of existence.

In 2019, Paul B. Preciado was invited to give a talk to a convention of 3,500 Freudian psychoanalysts in Paris—a talk that was jeered at by the Freudians, denounced, and shouted down before Preciado was even half-through. Not a single member of that group from Ecole de la Cause Freudienne would even admit to, for instance, being gay, when asked, a way of being the group asserts is pathological.

The entirety of Preciado’s speech has now been translated and published. Preciado, a trans man, has studied the history of psychology and legislation as it relates to defining “normality,” and finds it still primarily based on masculine identity and genitalia. Even women, according to these Freudians and Lacanians, are a sub-species or lesser example of the male ideal.

Gore Vidal in an essay once alluded to Freud as a Viennese novelist—no science, no research, just unexamined assumptions, and a hostility toward evidence (richly abundant from his own patients) at odds with his unsupported assertions. Lacan was even less of a scientist than Freud, even less of a writer, but couched his prose in dense absurdities difficult to unravel. (For those who made the effort to unravel his essays, the hard work revealed only unsubstantiated nonsense at its core.)

By defining what characterizes “male” and “female” and positing heterosexuality as the only nonpathological way of living and loving in the world, Freudians helped shape and determine the legal context in which people may be arrested, jailed, forcibly medicated, raped, operated upon, kept from employment, and so forth.

Just as Ptolemy and Galileo helped decenter the Sun, Earth, and humanity from Center of the Universe to small corner of an unremarkable galaxy among trillions of others, the notion of what it means to be human is undergoing a profound shift in understanding what is at the core of our being, no matter our genitalia, reproductive capacity, or preferences in intimacy. Living in a small corner of an unremarkable galaxy makes us no less human than before (or any less the children of God to theists)—any more than existing on a continuum of physiology and desires does.

William Burroughs, in The Book of Breeething [sic], argues for using the “as” of identity rather than the “is,” as shown in Egyptian hieroglyphs. In these hieroglyphs, the “as” of identity describes people according to functions they perform: X as uncle, as brickmaker, as citizen, etc. “Is” labels, however, are prone to limiting bigotries. The “is” of identity assumes that everything significant about that person is revealed by biological descriptors. For instance, “X is gay” (or Black or Jewish, etc.): “That’s all I need to know about him!” Preciado convincingly argues along similar lines for a human emancipation that frees us from destructive, limiting notions of what it means to be fully human to productive, varied, and affirming notions of existence, unshackled from genital obsession.

Weirdly Out West

Weirdly Out West

Rhys Hughes

Black Scat Books (Absurdist Texts & Documents No. 42)

Filled with puns and other word play, literary allusions, parodies, and tributes, Weirdly Out West is a smart and often very funny spoof of the Western genre, with bonus points for the mash-ups with other genres, such as the haikus that make up “The Narrow Path to the Far West” series.

Bulging sack splits wide

Coffee beans in horse trough fall

Pony Espresso

The dialogue in the stories often has the pacing of an absurd Marx Brothers or Firesign Theatre routine, as in this exchange between Apollonius, a talking horse, and his rider, Glen:

APOLLONIUS: I have a name and not just any name. It’s a classical name, the name of exactly the sort of artistic soul who composed epic verse in days of yore.

GLEN (frowning): In the days of my what?

APOLLONIUS: Just in the days of yore. They didn’t belong to you. They weren’t your days. They were the days of yore and belonged to others.

And then there are the fables, one-page mythic scenarios. Here is most of “The Wild Fables”:

The original gods of the West kept their fables in stables and only took them out occasionally but the classical gods who came with the settlers allowed their fables to graze free on the land. Needless to say, many of those fables escaped and went wild. Most were never recaptured and if a skilled cowboy happened to be lucky enough to successfully lasso one he could be sure it would never allow him to ride on its back. Broken bones still litter the remoter prairies as a result, enough to construct an irregular tower, if you are so inclined. The indigenous gods and the intruder gods will trade individual words on neutral territory but rarely full sentences. The mutual suspicion continues. Herds of fables come down to the river in the early evening to drink. They have interbred and now the stories are jumbled but strong.

Very silly, and thus recommended.

The Gentle Barbarian

The Gentle Barbarian

Bohumil Hrabal [Paul Wilson, trans.]

New Directions

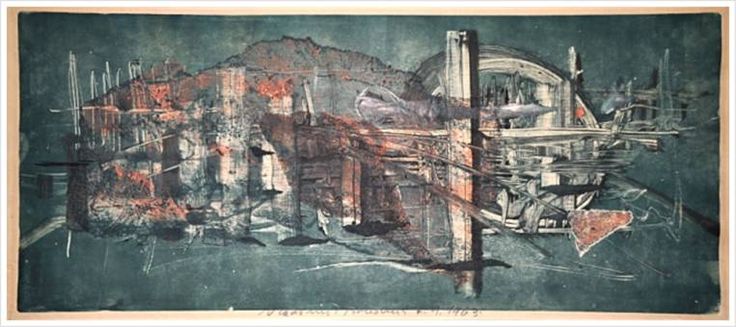

An influential Czech artist during the 1950s and ‘60s, Vladimir Boudnik was a close friend of Bohumil Hrabal, who wrote this brief memoir of their acquaintance as a tribute to him. When Hrabal says that this is a “poetic and truthful” account of their friendship, mutual friends of Hrabal and Boudnik are quick to point out that “poetic and truthful” does not mean “factual.”

Or no less factual than the bar talk and digressions that his novels are known for, allegedly largely built upon the stories he is told or overhears in the bars he haunts. Thus, The Gentle Barbarian is episodic, a series of set-pieces recounting the deeds of Boudnik alone or together with Hrabal. A third friend, Egon Bondy, usually hears of these accounts second-hand from Hrabal and provides the anecdote with its comedic conclusion about what a genius Boudnik is.

The repressive conditions they endure during Soviet control is only hinted at in Hrabal’s sketches:

When Vladimir got married a second time, in Cesky Krumlov, he asked me to be his best man. I was in for a surprise. I set out in my car but I couldn’t get out of Prague, neither through the city center, nor by using back routes, because the fraternal armies had arrived with their tanks to liquidate a nonexistent problem. So I returned home and then went to see an exhibition of modern American art in the Waldstein Riding School. I knocked on the gate, but the show had been postponed because the armies had arrived. When Egon Bondy heard about his, he shouted: “Goddamn it! That Vladimir! Will I ever have the good fortune to have so many armies set in motion because I’m getting married!”

Earlier in the book, Vladimir tells Hrabal and Egon Bondy how he came to be jailed for painting a picture of a brook running through the woods: “The pensioner called the police. He claimed there’s a boatyard of strategic importance to the state just past the inlet we were painting. We tried to explain that we were only interested in painting trees, but they brought us in anyway, and we had to make a sworn statement. I think we’re going to have to stick to humanist abstraction.”

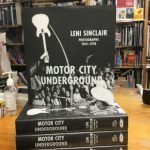

Motor City Underground: Leni Sinclair—Photographs 1963-1978

Motor City Underground: Leni Sinclair—Photographs 1963-1978

Cary Loren and Lorraine Wild, Editors

Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit

During the ‘60s and ‘70s Detroit had thriving, entwined sub-cultures united music, painting, and poetry with armed politics. At their nexus was Leni Sinclair, who documented the large milieu she and her husband John Sinclair circulated within, capturing the energy, tensions, and joys of the era. While turning the pages you may feel that, while you’re hearing the voice of young America again, it ain’t the Motown version but a complementary co-history of that era.

The MC5, Sun Ra, Tom Hayden, Alice Coltrane, Iggy Pop, Huey Newton, Aretha Franklin, and dozens more activists and artists, poets and partiers, musicians and mischief-makers appear throughout the book’s 400 pages of anti-war demonstrations, concerts, conferences, and rebellions.

Motor City Underground is beautifully designed and edited, a vital document of the time and a tribute to the photographer who kept a record of the time. The photo captions provide the context and significance of the events and people shown, and quotes from songs, statements, and reminiscences of the time are interspersed throughout, further explaining or exemplifying what is being documented. Cary Loren contributes an important 50-page essay, “Motor City Underground: Through the Lens of Leni Sinclar,” which begins as a biography of Sinclair but morphs about halfway through into biographies of the parts comprising the Motor City Underground. The book concludes with an interview with Sinclair.