For Poetry Month, Tom Bowden has provided a collection of reviews from recent small press poetry books. As usual, the titles are linked to our affiliate pages on Bookshop.org — please feel free to contact Book Beat where these books are either in stock now or can be ordered directly.

Ellis Island

Ellis Island

By Georges Perec (Harry Mathews, trans.)

New Directions

About three-quarters through Perec’s graceful and intriguing poetic essay on Ellis Island, I started asking myself, “What’s Ellis Island to Perec?” He never emigrated to the U.S. as had so many other Europeans, including Frenchmen like himself.

Ellis Island is the script to a documentary Perec wrote in 1978 in collaboration with director Robert Bobo (whose own great-grandfather, with trachoma, was turned back at Ellis Island), filmed long before the buildings and grounds of the island had been restored as a National Park tour site, and long after they had been scavenged for scrap metal.

Perec was a great one for lists, and they are here: the questions asked of emigrants during the 25 years the island served as the gateway to the continent; the tests and observations emigrants had to pass; the number rejected from America, and the number who committed suicide on the island; the seats, desks, and walls used; and so forth.

Of course, in trying to sus out Perec’s relationship to Ellis Island, I was looking at him the wrong way, as a Frenchman, not as a Jew, whose parents—not mentioned by Perec (father killed by a German, mother dead in Auschwitz)—orphaned him by age 9. “To me Ellis Island . . . / . . . in my mind is linked / in a most confused and intimate way / with the fact of being a Jew.”

like near and distant cousins of mine

I might have been born

in Haifa, Baltimore or Vancouver

I might have been Argentinean, Australian, English or

Swedish,

but in the almost unlimited range of

possibilities,

I could not be born in the country of my ancestors,

in Lubartow or Warsaw,

or grow up there, in the continuity of tradition,

language, and community.

Those who could not be born elsewhere often came here instead.

Mónica de la Torre’s afterward provides excellent context for this essay within the history of U.S. immigration policies, up to the present day.

The Voices & Other Poems

The Voices & Other Poems

By Rainer Maria Rilke (Kristofor Minta, trans.)

Sublunary Editions

A selection of Rilke’s poems by translator Kristofor Minta, those that “seem[ ] to care less about managing our perception than [they do] about piercing to the heart of things.” Poems, in other words, about the down-and-out, such as these lines from “The Song of the Widow”:

Fate wants back not only the happiness,

it wants the howls and the anguish,

then picks up the ruins for cheap.

Fate was there, and for next to nothing,

got every expression on my face,

down to the mood.

It was a daily selloff

and when I was empty, it gave me up

and left me standing open.

Mintas translations are lissome; the themes and descriptions sound as if Rilke were writing just yesterday.

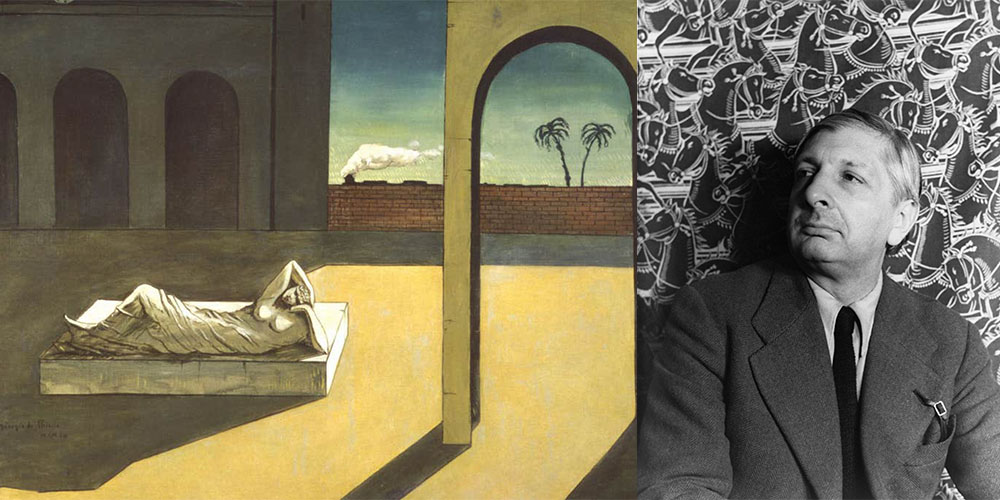

Geometry of Shadows

Geometry of Shadows

By Giorgio de Chirico (Stefania Heim, trans.)

A Public Space Books

Collecting all the poetry de Chirico wrote in Italian, this bi-lingual edition shows his ability to also say in words what he shows in paintings, with equal sense of odd precision and aptness. In “Epode” he writes,

One day I too will be a man of marble

Widowed husband on the Etruscan sarcophagus.

That day, maternal cities, squeeze me

In your great embrace

Of stone.

I suppose some of these pieces could be read as ekphrastic poems for paintings that don’t exist: That is, they often read the way di Chrico painted; they can be imagined through the lens of his paintings’ vocabulary. Here is the entirety of “Sunday”:

It is Sunday, it is morning, it is winter.

Yesterday I finished my painting.

But the heart is very sad.

I see people going to church.

Someone has gone to hunt,

someone to fish, but the rain

falls, soft soft, and sweetly

murmurs that all is vain.

I think this passage exemplifies the general quality of Stefania Heim’s translation. She’s also written a brief introductory essay on the place of di Chirico’s Italian poetry among his works.

“With a word, de Chirico made languages collide . . . In translation, I have tried to honor these textures, to stay hovering just a bit between… Metaphor, juxtaposition, unsettling connections, meaning evoked in the missing connective tissue between somehow familiar objects—these are a poet’s tools. De Chirico cultivated this association. He addresses the two “goddesses:” “true Poetry” and “true Painting.” With allusion, symbols, and mythmaking, he connects his work to the great striving of the ages.” –Stefania Heim from her revised online introduction to de Chirico’s poetry, in ASYMPTOTE

LEFT: GIORGIO DE CHIRICO, THE SOOTHSAYER’S RECOMPENSE, 1913 RIGHT: DE CHERICO IN 1936, PHOTOGRAPHED BY CARL VAN VECHTEN

Acrobat

Acrobat

By Nabaneeta Dev Sen (Nandana Dev Sen, trans.)

Archipelago Books

Poetry on the experiences of womanhood over a lifetime; more specifically, as a Bengali-speaking woman in India. Sen, who lived from 1938-2019, was an award-winning writer whose works ranged from academic essays to books for children.

Her poetry too shows a wide range of capability—from angry renunciation of womanhood to erotic prelude—on facing pages! In “Renunciation” we hear

Mother, take back my dreams, my memories. . .

Everything you gave me, take it all.

A mother’s love, the fondness of a friend,

Victory, wonder.

I’ll unwrap my pouch and easily throw away

The blood-soaked placenta. . .

Then, only a few lines later on the next page in “Green Salad for My Husband,” we’re told

I have a shock of green ideas upon my head

Ever so green

Ever so raw

Unwashed

Garden-fresh

With pesticides seeping through

A fine salad for my gourmet husband.

And the middle view is represented, too, in “Puppet”:

I can’t decide, was it a mistake? Or is it better this way?

Twice now, pretending to be a goddess,

I’ve created humans out of my desire.

Funnily, though, that’s where the fake goddess act ends.

After that, you revert to being a woman, as before. . .

Exhausted on the Cross

Exhausted on the Cross

By Najwan Darwish (Kareem James abu-Zeid, trans.)

NYRB Poets

In the morning, I’ll go down to the square

and sit among you

and wait.

Have I ever been,

my whole life

anything but a worker, waiting?

I’m Egyptian, too.

I look out of this pit and see my grandmother Cleopatra

handing Africa over

to Mark Antony. . .

Then I go back staring at the mud.

I’m Egyptian, too.

—from “A Worker, Waiting (to the Egyptian day laborers in Jordan)”

A Palestinian born in Jerusalem in 1978, Darwish’s poems describe Pan-Arab experiences in terms of both their shared humanity with the rest of the world and as specifically Arab experiences—the twists that make the experiences uniquely theirs.

“We were born into exile,” he writes in “To Lament a Mountain,” “but we still think we’re mountains— / mountains unmoved by the wind.” And those unmoved mountains are fond of recalling the voice of Warda, an Algerian-born singer of Egyptian songs:

Her voice has the look of a man condemned,

who walks to the gallows willingly

but is not hanged.

Instead they tell him, “Go now.

Your punishment is love.”

—from “Imagine Someone”

Imagine those melodies as poems.

God Is a Bitch Too

God Is a Bitch Too

By María Paz Guerrero (Camilo Roldán, trans.)

Ugly Duckling Press / Señal #13

god eats ham

and it’s going to give him cancer

god likes sausage

he’s addicted to buttery pastries

. . .

god is 53 years old

wrinkled

god is menopausal

is outraged

hates his bloated body

god is now a broad-backed fridge

god has lost his curves

god is temporal and tie attacks his figure god goes out dancing

with his new body

and his faded face

takes a seat at a table in the salsa club

because god is also

Latin American

An exploration of cultural un-confidence by a Columbian poet. Like Walt Whitman, María Paz Guerrero’s god contains multitudes; yet, whereas Whitman’s multitudes indicate plenitude, Paz Guerrero’s indicate lack: “we have one axis two axes lack and guilt.” The poem describes a plentitude of lack but leaves the guilt implied, a guilt which amounts to uncertainty whether the cultural limitations of one’s nation—limitations imposed by personal economy and national proximity to the world stage—allow the aspiring third-world intellectual claim peer-status with the “really prodigious kids” who “speak three languages and study double majors.”

The most significant lacks concern of cultural historical knowledge and the ability to measure up to one’s peers in the United States, for fear of being seen as hopelessly naïve and unschooled. (An unfortunate fear, given that Paz Guerrero was educated at the New Sorbonne University in Paris and now serves as a professor of creative writing at Universidad Central in Bogotá. Of course, achievement does not necessarily equal confidence.

god lives at near material poverty-level but regularly buys books out of a felt duty to a world-wide community of writers who communicate with each other across geographic and chronological distances, a god, who, on the margins of this universe, elbows her way in.

Spring Cleaning

Spring Cleaning

By Marshall Bood

Ugly Duckling Presse

A chapbook of five poems, the longest (“Neighbourhood Cleanup”) taking up 21 of the book’s 29 pages, Spring Cleaning is immersed in the lives of the impoverished, unmedicated and addicted:

two teenagers smoking

on the stoop

of the house declared

Unsanitary and Unfit

for Occupation . . .

a one-armed homeless man

holds dirty jeans up

styrofoam cup clenched

in his mouth

waiting

everyone drawn

to the lights

of 7-11 . . .

moths or near-

death experiences

The title poem offers the one suggestion found in the book of hope and the need for self-respect—a tough love of the self. Prefacing the following poems reflecting on loss, it begins, “Straightened the books / Dreams pushed aside again / No-one to discipline me; / I discipline myself.”

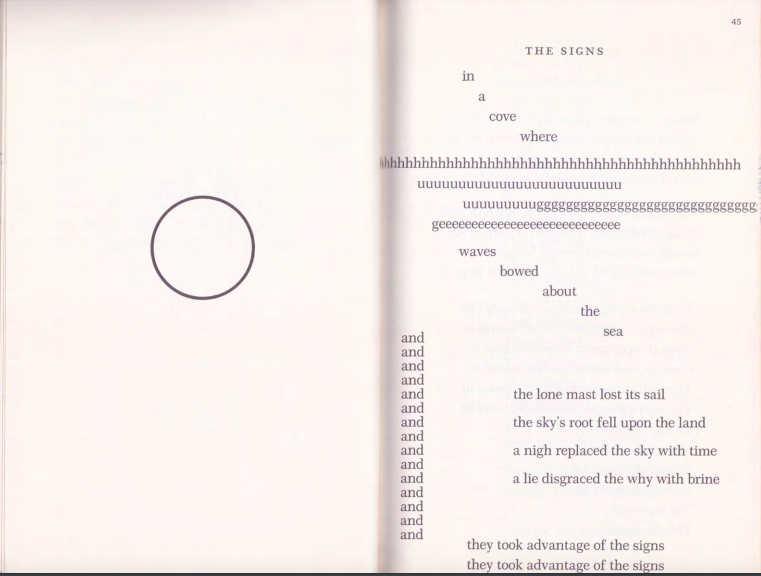

The Matrix—Poems: 1960-1970

The Matrix—Poems: 1960-1970

By N. H. Pritchard

Primary Information / Ugly Duckling Presse

Originally published by Doubleday in 1970, The Matrix quickly slipped away from attention despite its visual and linguistic vangardism that remains as relevant and challenging today. Mixing the elements of concrete poetry with the mantra to “make it new,” Pritchard’s often poetry forces readers to slow down to re-create and re-enact the act of imposing meaning on imagination:

enco ache d di stance

str etches o ftim e

u nre ad able

f ort hem isten velop es

wh ere

b eeps b eat

dark

emer gence

ofg host lyfi gure

inhe avy c oat edol d

k n ow in g

not hing

Pritchard forces the reader to consider the material of poetry—the words and paper it’s on, the negative and positive spaces—in conjunction with the semantics of word and vision and how we understand taking apart and reassembling human sensual and intellectual affirmation.

Poetry

The Fall of America Journals, 1965-1971

The Fall of America Journals, 1965-1971

By Allen Ginsberg

University of Minnesota Press

Covering the period that Allen Ginsberg wrote The Fall of America, these journals include first drafts of many of the poems included in that book (and others, later), previously unpublished “auto-poesy” (spontaneous poetry tape-recorded by Ginsberg while in a car) and poetry, plus observations of these United States, circa the late ‘60s, from coast to coast by air, car, and rail. Viet Nam, the Democratic Convention in Chicago, demonstrations, bucolic musings on rural retreats, sex, Burroughs and Kerouac, a series of visits with Ezra Pound in Italy, and so forth—just what one would expect from an artist to seemed to be everywhere, attracting everyone to his orbit.

Other books based on Ginsberg’s journals include The Book of Martyrdom and Artifice: First Journals and Poems: 1937-1952, Journals Mid-Fifties: 1954-1958</em>, South American Journals: January–July 1960, Indian Journals: Notebooks, Diary, Blank Pages, Writings March 1962 – May 1963, and Iron Curtain Journals: January–May 1965

https://youtu.be/aZQ1F45j8Vc

Wicked Enchantment: Selected Poems

Wicked Enchantment: Selected Poems

By Wanda Coleman

Black Sparrow Press

American poet Wanda Coleman lived life on the socio-economic fringes—perpetually impoverished (“I have / been three months behind in my rent for thirty years”) and constrained by a culture that rejected her on the basis of skin color, gender, and lack of college education, Coleman fights back for dignity and beauty in life in poems ranging from brash self-assertion to exhausted, emotional pleas about an existence heavily and perpetually constrained by lack of food and economic security. This life, in spite of having won the Lenore Marshall Prize from the American Academy of Poets in 1998 and, in 2001, being nominated for a National Book Award in Poetry.

Hardscrabble life described by the right hands produced the type of poetry and fiction attractive to John Martin, publisher and editor of Black Sparrow Books, perhaps best known for publishing works by Charles Bukowski and John Fante, and adding Coleman in the 1970s. Not surprisingly, Coleman felt some kinship with the poverty and low-wage jobs described in Bukowski’s poems—and some of her early poems here reflect that inspiration—but she soon developed her own style and voice, and expanded her vocabulary, forms, and rhetorical expression beyond the more limited constraints of Bukowski’s works. Except for the poems of lust (lust on a zero $ budget—not romantic), the following two stanzas from “Things No One Knows” are representative of Coleman’s themes and frustrations:

overcome by the stink of mildewed wash, i have

been three months behind in my rent for thirty years. my

countrymen do not love me. even my lines have

lines. we are getting old in a city where the old are

invisible. i have nothing new to eat and barely five minutes

to use the jane. and less time than that to revisit my

father’s grave. i’ve worn the same underwear for fifteen

of those thirty years and some pieces longer than that

writing friends is a luxury, enemies a necessity. my car

was stripped and stolen months ago and I have no

money with which to repair or replace it. my mentors have

exiled me to the outskirts of nappy literacy. my wallet is

dying of militant brain cancer. my lust for my country

is frigid. the light excludes me and there is

no degree for what is learned in the dark

“Few poets of any stripe write with as much forthrightness about poverty, about literary ambition, about depression, about our violent, fragile passions.” —The Wicked Candor of Wanda Coleman, The Paris Review

Allegria

Allegria

By Giuseppe Ungaretti (Geoffrey Brock, trans.)

Archipelago Books

Born in Egypt in 1888 to Italian parents, Guiseppe Ungaretti moved to Paris in 1915, then joined the Italian army at the outbreak of World War I, where he wrote in the trenches the poems comprising Allegria. The poems are spare expressions of the extremes of emotions when surrounded by death. Here is “Vigil” in its entirety:

all night long

flung beside

a butchered

comrade

his teeth

bared

to the full moon

the bloating

of his hands

entering

my silence

I wrote

letters full of love

I’ve never felt

so fastened

to life

In the teeth of war, the poems yearn for silence as an ideal form—“To drowse there / alone / in a distant café / in a light / as faint / as this moon’s” (from “Once Upon a Time”); “Nothing / but grumble / of crickets / reaches me now // It keeps my troubles / company” (“Sleepiness”)

After the exhaustion of endless murder, an emotional surrender, during the return home, to the horrors of war and the future:

Farewell, desires and regrets.

Of past and future I know as much as a man can know.

Already I know my fate, and my origin.

Nothing is left for me to desecrate, or dream about.

I have enjoyed and suffered it all; nothing is left but to

make peace with death.

Which means calmly raising some children. (from “Lucca”)

Geoffrey Brock’s translation is seamlessly rendered into English, suggesting an original composed of simple, common words that easily evoke the poet’s thoughts and senses.

Dearly

Dearly

By Margaret Atwood

Ecco Press

Sly, smart, and inventive, the content of Margaret Atwood’s poetry matches her prose: expressing environmental worries; revisiting / revising myths, fairy tales, and stereotypes; and, in advancing age and the death of her husband, confronting mortality and fragility.

Who was it used to complain

he didn’t have a brain?

Some straw-man cloth boy.

Me, it’s the heart:

that’s the part lacking.

I used to want one:

a dainty cushion of red silk

dangling from a blood ribbon,

fit for sticking pins in.

But I’ve changed my mind.

Hearts hurt. (from “The Tin Woodwoman Gets a Massage”)

In “Princess Clothing,” Atwood considers the forms of adornment that women are shamed or killed over: Burkas, animal fur, uncovered heads, uncovered feet, and so forth:

Too many people talk about what she should wear

so she will be fashionable, or at least

so she will not be killed.

Women have moved in next door

wrapped in pieces of cloth

that lack approval.

They’re setting a bad example.

Get out the stones.

Pitfalls await us everywhere—particularly women—, and Atwood is too wise to be snookered by sparkles.