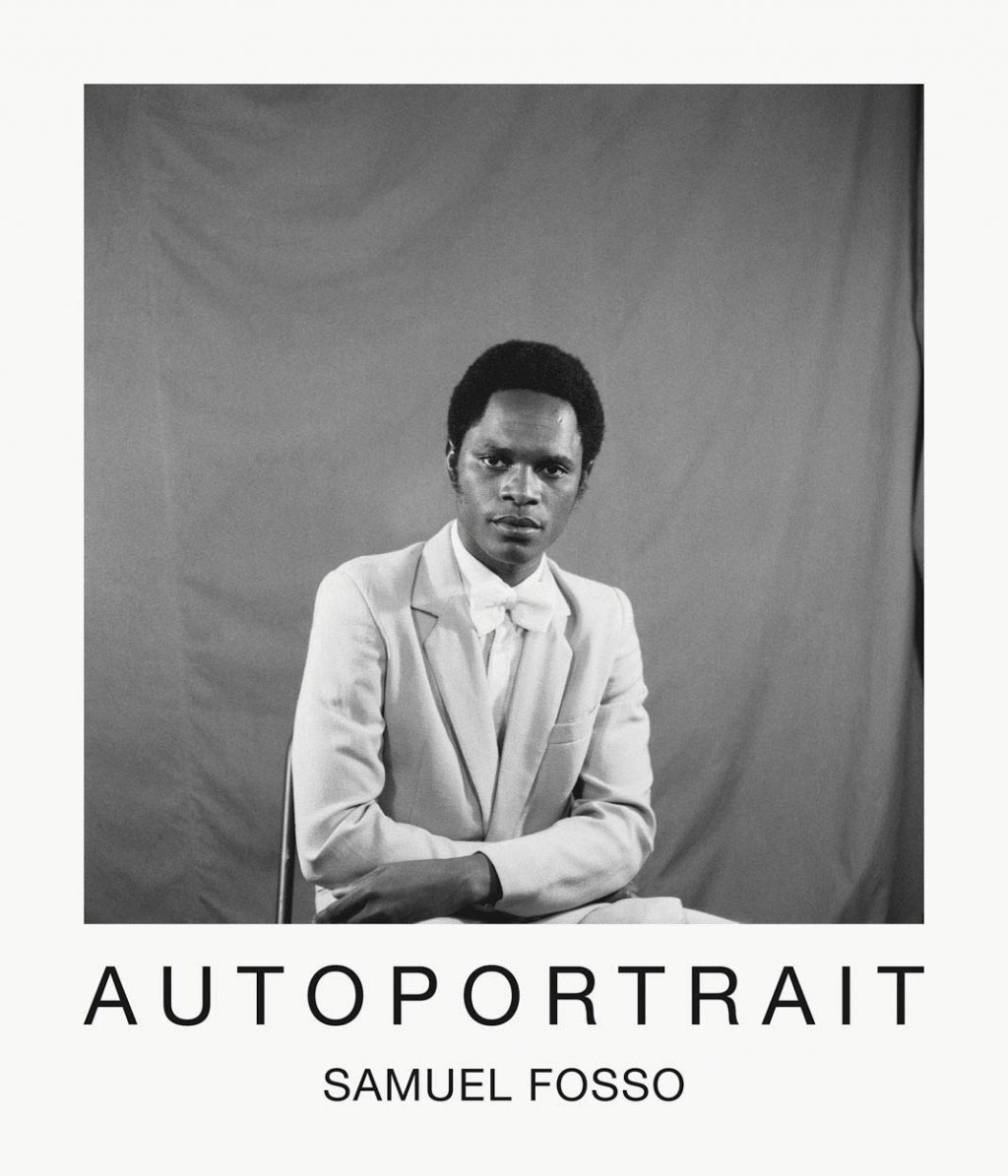

Autoportrait

Autoportrait

Samuel Fosso

Steidl Verlag / The Walther Collection

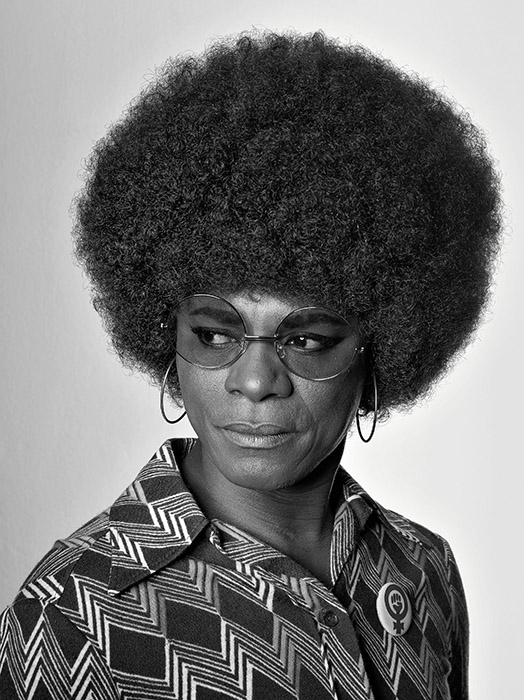

Born in 1962 to Nigerian parents in Cameroon, Samuel Fosso moved at age 10 to Central African Republic to live with his uncle after both his parents had died. Once with his uncle, he came upon a photography studio in town, asked to serve as an apprentice, and by age 13 (!) set up his own commercial portrait studio. To let his beloved grandmother know how he was doing, Fosso used the unexposed film at the end of the rolls to photograph himself in various poses and guises, many based upon images found in fashion magazines.

The photographs are positive, self-assured, and aware of the gaze they hope to provoke. Mimicking these images required him to learn and master the film and lighting techniques they used. It also gave him a place to inhabit the roles and postures shot, a sort of acting one frame at a time. Of course Cindy Sherman comes to mind, but Fosso began this work in the mid-‘70s half a planet away.

Since those early works, Fosso has developed a body of work in which he explores (and inhabits) a variety of roles—as enacting a variety of dreams he imagines his grandfather having, re-enacting himself in his house as his neighbor and friend across the way is beaten and murdered by the police, posing as the Africans and African-diaspora whose influence on him embodies the African spirit unifying all of them, and so forth. Fosso’s work is historical, political, personal, comedic, serious, and artistic.

I don’t how to take his series “Emperor of Africa” as anything but parodic. In/as the “Emperor,” Fosso re-enacts a series of photographs of Mao Zedong taken during his reign of mass murder. With the Chinese government currently exploiting African resources in the grand Western tradition, the series also has implications for local government corruption in answering the question, “Do Africans really run Africa?”

Autoportrait is a comprehensive, career-spanning overview of one the world’s pre-eminent photographers. In addition to a biographical interview with Fosso, each portfolio from his various projects is followed by an accessible essay that explains the works’ background. Highly recommended.

The Shadow Elephant

The Shadow Elephant

By Nadine Robert and Valerio Vidali (Sarah Klinger, trans.)

Enchanted Lion Books

This simple, low-key book for young children explores the feeling of sadness. In contrasting images of dark blue (for the sad elephant) and colors (for the elephant’s friends), a story is told in which none of the elephant’s caring friends is able to distract him from his mood. As we find out, distraction isn’t what the elephant wants—just quiet time together with a friend to talk about their sadness together, and through that unity come to feel hope again.

Mysterious Solidarities

Mysterious Solidarities

By Pascal Quignard (Chris Turner, trans.)

Seagull Books

“Claire Methuen travels back to her hometown . . . for a family wedding, [where] she runs into her old piano teacher Madame Ladon,” who wills Claire the modest estate Claire moves into. Returned to her childhood haunts, Claire “becomes increasingly obsessed by her childhood sweetheart, Simon Quelen, who, now married and a father, still lives in a village further down the coast where he is the local pharmacist and mayor,” and who will go on to commit suicide because it is impossible for him divorce his wife to be with Claire. Claire spends the rest of the novel roaming the beach and heathland, occasionally accompanied by her younger brother, Paul, scanning the ocean at the site of Simon’s suicide, which she witnesses. (Quotations from Seagull’s publicity people.)

I am ambivalent about the novel. Quinard does well at establishing mood and evoking scenes—the book is made up of vignettes from the points of view of the novel’s various characters and locals who offer eyewitness testimony skewed through the lens of local lore. But another part of me resists the abundance of deaths, suicides, and accidents in one family as soap-opera goth-lite with obsessive love in the fore, as Poe on the beach.

South Central

South Central

By Mark Steinmetz

Nazraeli Press

Photographed in the economic outskirts of Knoxville when payphones and satellite dishes still roamed the planet (i.e., the ‘90s). Care-worn expressions haunt the faces, starting in childhood, and phrases with the word “security” are probably unknown. Most subjects agreed to be photographed and seem affectless. Economic abandonment pervades the photographs, as does the stress, anger, and unease of the people empathetically shown here.

The Locusts

The Locusts

By Jesse Lenz

Charcoal Press

Photos 2017-2020 of Lenz’s children playing on the rural grounds of their house in Ohio. . . Apart from those spare facts about the book gleaned from the publisher’s PR materials, I wouldn’t know where in the Midwest the photographed events occurred, or when within the past five decades. What Lenz captures here are the (vanishing) experiences of youth that get overlooked when the past is sentimentalized.

The Locusts is a beautiful, accurate depiction of youth—from 6 to 10, say—when allowed to discover nature unfiltered: death, love, and observation, up-close and personal. The children in The Locusts encounter animal corpses in the farmlands around them; they turn over, poke at, and hold up carcasses, discover skeletons. Lenz shows what for me is the child’s-eye-view of intently watching insects and wildlife going about their business. Life in nature is wild and dangerous; children intuit and respond favorably to the challenge, adjusting their fright:fight ratios.

Lady Marjory Allen (“Better a broken bone than a broken spirit”) would thoroughly approve of the childhoods shown here: the body’s limits tested, the natural world tested—sometimes to the body’s limits. As long as nobody’s going to jail, there’s nothing to worry about, Mom and Dad!

And yes, the production values are excellent, Lenz’s B&W photos and well-nuanced with details outside the focal point that subtly support each photo’s emotion. The photographic reproduction is beautifully detailed.

Smoke Signal #35

Smoke Signal #35

By Hironori Kikuchi

Desert Island Comics

Twenty-eight pages of tabloid-sized newsprint showcasing the hallucinogenic images of Hironori Kikuchi, an artist who lives a rural area of Japan, where he has been publishing since 1995. Beyond being merely strange, Kikuchi designs the many of his images to look like glyphs from alien or forgotten cultures—but nothing you’d necessarily want to witness first-hand.

Marshlands

Marshlands

By André Gide [Damion Searls, translator]

NYRB Classics

“I draw up from my daily planner the sentiment of duty: I write in it a week in advance, so that I have time to forget what I wrote; surprises are always lying in wait, which are indispensable, given my way of life. I go to sleep every night facing a day to come that is unknown and nonetheless predetermined by me.”

An early work by Gide, Marshlands is a comedy about the late-19th-century equivalent of an “artistic” hipster / poseur. Not a fop—which would require an obsession with fashion and bon mots, neither in evidence here—the narrator does however socialize daily, much to the detriment of his time spent writing—largely a banal one- or two-paragraph observation he manages to come up with every few days.

He is writing a book called Marshlands, featuring a protagonist named Tityrus, his alter ego. But what Marshlands is / will be about changes by the moment. At least we have hints of what he intends to be in it, by both the lists he makes about what it should describe and what it actually does describe. Although the narrator reacts with exasperation when his friends, after hearing or telling an anecdote, tell him “You should put that in Marshlands,” he does put it in Marshlands because we’re reading it. And although the notes from Marshlands he shows tend to be silly or trite, his writing as the narrator of the book we’re reading is better than that of the book he’s writing.

Stalingrad

Stalingrad

By Vasily Grossman [Robert Chandler and Elizabeth Chandler, translators]

NYRB Classics

Vasily Grossman, who witnessed the devastated Stalingrad and talked to its citizens and soldiers, wanted to create another panoramic epic of the war equal to Tolstoy’s War and Peace with a theme equal to that of War and Peace. The scale is large, though occurring over the space of a single summer—multigenerational, multi-ethnic—encompassing social rank as well as moral, ethical, and political duty at the risk of life. Heroes walk here, as do cads. Love is known, kept, and lost. Being an admired character does nothing to suspend a character’s life—we, too, lose what matters to us.

The novel begins after the start of WWII and Hitler’s assault on the USSR, Germany troops quickly and easily slicing through Russian territory, with little significant resistance. Before the siege of Stalingrad, we are introduced to characters from various parts of the union—returning home from the front, leaving home for the front, staying behind to help the war effort, and so on—from cities to countryside, from farms to high-ranking military offices. Sons, daughters, grandparents, grandchildren all strive to exist under extreme conditions, as do factory workers, farmers, soldiers, nurses, and doctors—male and female alike.

Actual fighting takes up a smaller portion of this 900-page brick (closer to 1,100 pages including notes and the afterword), and the novel ends before the siege. (Part 2, Life and Fate, another 1,000-page, picks up with the same (remaining) characters of Part 1 after the siege.) Despite offering up this tome as an homage to Russian bravery, Soviet censors managed to be offended by the original manuscript, which underwent revisions before it was able to be published—after Part 2. Stalingrad’s translators, the Chandlers, have done their best to re-create the ur-text submitted by Grossman. Since I am not a student of Russian language, literature, or publishing practices, I cannot say with the authority of a scholar how their achievement stands in those regards.

However, as a novel in the Russian tradition of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky (both of differing temperaments regarding each other as well as Grossman) in particular and the 19th-century Western European practice of cranking out 700-900-page books, Stalingrad fits well while also extending the tradition. Although I’m tempted to now pick up the copy of Life and Fate that has sat unread on my shelves for decades, Robert Chandler, in his afterword, says that he is contemplating re-translating it, since he now has available manuscript pages that were inaccessible before the fall of the Soviet Union. A good companion to this novel to compare Grossman’s realism to what actually occurred would be Svetlana Alexievich’s Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II.