Wakefield Press is a Cambridge, Massachusetts independent press, publishing works in translation by famous and lesser known authors in beautifully designed paperback editions. Tom Bowden interviews publisher Marc Lowenthal, and translators Jamie Richards, Erik Butler and Scott Nicolay, concluding with short reviews of selected titles. Wakefield Press is a labor of love, supported by indie bookstores and devoted readers of weird, surrealist, and avant-garde writing. Their books can be found at Bookshop.org, and direct from Book Beat.

Wakefield Press, an Appreciation by Tom Bowden

Founded in 2009 by Marc Lowenthal and Judy Feldmann, Wakefield Press set out “to increase the availability in English of obscure and avant-garde authors from the past who wrote in foreign languages.”

Founded in 2009 by Marc Lowenthal and Judy Feldmann, Wakefield Press set out “to increase the availability in English of obscure and avant-garde authors from the past who wrote in foreign languages.”

Define “obscure”? OK. The categories and sub-categories by which Wakefield promotes its books include Imagining Architecture—fantastical architecture, imaginary urbanism, and hallucinatory dwellings; Imagining Science—outsider science, extreme empiricism, aberrant experiments, and imaginary speculations; The Library of Cruelty; The Margins of Dada; The School of the Strange; Subverse; and The Envelope—Silence: A Surrealist Library.

The books, authors, and topics share eccentricities, generously portioned. Balzac, Perec, and Huymans may be the best-known of their authors; others were popular in their time and are ripe for rediscovery; and others may not have been well-known even in their own time but are overdue for an audience.

Interview with the publisher, Marc Lowenthal

TB: The entry on Wikipedia about Wakefield says that “The aim of the company is to increase the availability in English of obscure and avant-garde authors from the past who wrote in foreign languages.” But to be clear, by “avant-garde” Wakefield does not mean “difficult, hard-to-follow” à la Finnegans Wake or other Modernist pinnacles. How would you describe the literary vanguard(s) you’re drawing attention to?

ML: Indeed, I wouldn’t say the authors we publish are difficult to read. But “avant-garde” has taken on a range of nuances over the past century, with the general one being a sense of pushing against a cultural status quo. Since we’re primarily focused on historical literary works on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, what was once considered to form the avant-garde—Dada and Surrealism, for example—represents something different today than it did a century ago: still challenging if the reader is expecting a conventional novel, but not as bewildering as when it had first manifested itself. I personally lean to adjectives like “eccentric” in thinking about these things (or how our overseas colleague, Atlas Press, defines their publishing mission as covering the “anti-tradition”), but I will say that the cultural status quo I do find interesting to push against is that of the canon, be it the writers left out of it, or overlooked aspects to writers in it (however Balzac was regarded in his day, he is solidly in the canon today, but I find it more interesting to look at his lesser-known essays than at his novels, for example). And one could define the avant-garde as being that which eventually makes up the canon. Kafka was a little-known, extremely eccentric and experimental author in his day; nobody considers him to be a “difficult” read today, but that is because we’ve developed categories and concepts through which we read him more easily (including that infamous concept that generated out of his work, “Kafkaesque”). But the process is never-ending; some publishers are continuing to bring out his writings in new translations now that he is in the public domain; I’m interested in exploring some of his German-language contemporaries and representing them better (Ferdinand Hardekopf, Alfred Lichtenstein, etc.).

None of that really describes the literary vanguards you asked about, though. Maybe I’m avoiding doing so to avoid the risk of getting programmatic. The same way that Borges had described Kafka as having created his precursors (who, when set side by side, may prove to have no commonality) rather than vice versa, one modifies the past when one presents or publishes it. All this is to say that Wakefield is interested in publishing “missing pieces,” but the puzzle they belong to isn’t one I’d currently like to define.

TB: Wakefield has passed the 10-year mark, which is a milestone for any endeavor, let alone a literary endeavor. What do you think that Wakefield’s books are tapping into that appeals to audiences now and/or that audiences respond favorably to decade after decade? What is your sense of your audience, of who they are?

ML: I actually missed that 10-year mark, but it is something to celebrate. It really is tough for independent publishers to maintain the momentum year after year, as enthusiasm is really the primary ingredient to keeping things going. I think the publishing world we inhabit these days shares some of the characteristics of the music industry (I’m thinking of something like Numero Group’s Eccentric Soul series, for example), where music lovers seek out lesser-known or newly discovered aspects to the music they love. All of which has opened up over the last couple decades through the internet, where smaller communities can come together even if they’re geographically separated. At a certain point in your listening life you might stop listening to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and start seeking out Os Mutantes or Can instead (not that they’re obscure today the way they were for me when I was in high school).

I think there are roughly 300 people out there who trust our publishing program to the extent that they will pick up whatever we publish—the way I do with some publishers, with whom, even if I end up not liking a particular title they’ve published, I still want it and read it because it forms a part of a larger whole that they represent for me. Anything beyond that really breaks down title by title. I think we can take some credit for bringing broader attention to some authors we’ve published (Marcel Schwob, Paul Scheerbart); others remain only a tad less unknown in English than they had been before we published them…

TB: At the outset, Wakefield only published works by deceased authors. Brief Lives of Idiots is the first title published by a living author—a book whose tone is utterly apiece with that other cataloguers of human behavior: Balzac, Louÿs, Fourier, etc. Do you foresee publishing more books by living authors?

ML: Gisèle Prassinos would have actually been our first living, if very old, author, but she actually passed away before we brought out her collected stories. But we have previously published the living Pascal Quignard’s A Terrace in Rome and our first Romanian (and living) author, T. O. Bobe, with his little book, Curl. But yes, we have a proclivity for the historical and the deceased as a rule. There are publishers like Open Letter, Dalkey Archive, And Other Stories, Europa, etc., who are focused on living contemporary authors, but they also have publicists working to promote their lists and authors. Wakefield is just my wife and myself and we both work day jobs: standard publishing needs such as marketing and publicity are not something I’m able to devote resources to, and a contemporary author requires a certain kind of attention that I’m not able to provide. Though that aside, I am more inclined to search through library stacks than the Frankfurt Book Fair.

ML: Gisèle Prassinos would have actually been our first living, if very old, author, but she actually passed away before we brought out her collected stories. But we have previously published the living Pascal Quignard’s A Terrace in Rome and our first Romanian (and living) author, T. O. Bobe, with his little book, Curl. But yes, we have a proclivity for the historical and the deceased as a rule. There are publishers like Open Letter, Dalkey Archive, And Other Stories, Europa, etc., who are focused on living contemporary authors, but they also have publicists working to promote their lists and authors. Wakefield is just my wife and myself and we both work day jobs: standard publishing needs such as marketing and publicity are not something I’m able to devote resources to, and a contemporary author requires a certain kind of attention that I’m not able to provide. Though that aside, I am more inclined to search through library stacks than the Frankfurt Book Fair.

That said, I’m not averse to living authors, though as you point out, I would want them to resonate with our list. Someone actually expressed surprise to me that Ermanno Cavazzoni (author of Brief Lives of Idiots) is alive—I’m presuming because he seemed to fit so comfortably into our list. I’m very fond of his work and intend to bring more of his books out in English. Overall, the living will need to be a smaller portion of our list, but there will be some others. The living Alain-Paul Mallard, for example, whose slim, Borgesian Evocation of Matthias Stimmberg we’ll be bringing out later this year.

TB: Who else should readers of Wakefield’s books read—authors, additional publishers?

ML: I suspect most of our readers are pretty savvy when it comes to English-language publishers whose catalogs would interest them, but anyone who likes what we put out will like the publishing program of Atlas Press or Twisted Spoon Press—two publishers of translations I read with enthusiasm. Rixdorf Editions is a new labor of love based in Berlin, focused on bringing out underrecognized German texts of the pre-Weimar period; James J. Conway, who started it, writes the Strange Flowers blog, a “cabinet of human curiosities” that should appeal to and inform readers of our list: his year-end “Secret Satan” post always rounds up a lengthy list of books that had come out over the year and had completely escaped my radar.

Siglio has carved out an interesting body of hybrid books straddling the literary/art divide that don’t fit into any other easy categorization than “Siglio.”

And finally (though for the sake of disclosure I should mention that my day job overlaps with their activities), discovering Strange Attractor a few years ago gave me that rare dreamlike pleasure of discovering what felt like a secret room I hadn’t known existed: they’ve been publishing a body of books interweaving occult accounts and life histories that really make them one of the more unique and exciting publishers going right now. Their publication of Amy Hale’s long-awaited book on Ithell Colquhoun (Genius of the Fern Loved Gulley) should be entering the market shortly, which I’m eager to read.

TB: What’s coming up, and what is on your wish list—what you would love to publish, and how?

ML: The pipeline is a bit overstuffed (ambition and over-commitment are usually the main factors to lead to an indie publisher’s demise, I should note). This spring we’re continuing with our program of bringing out the Belgian Jean Ray’s work into English with his fifth, and best-known, book, the weird-horror novel Malpertuis, along with our biggest book to date, the Mauritian Malcolm de Chazal’s Sens-Plastique, an aphoristic work that maps all of nature onto the human body (and which contains some of the most poetic analogies for the sex act that I think are to be found). Along with that will be another forgotten German author of the Expressionist era, Curt Corrinth, and what in his time had been an infamous short novel, Potsdamer Platz, or The Nights of the New Messiah: Ecstatic Visions, which he wrote under the influence of Austrian psychoanalyst Otto Gross and his theory that sexual orgies could liberate people from their inhibitions. And Robert Desnos’s novel, which we’re titling The Die Is Cast (the title is difficult to translate but could be rendered in a number of ways: The Bed Is Made, etc.). Atlas Press has published most of Desnos’s surrealist prose in English; this was his semi-social-realist novel that he somehow managed to publish during the Paris Occupation when he was working with the Resistance, about drug addiction among a group of misfits. The translator has described it as a pre-War Parisian Trainspotting.

I’m still working out our fall season, but it will include The Mill: A Cosmos, the sole prose work of the rather unknown Expressionist poet Bess Brenck Kalischer (the only visual document of her that I know of is a somewhat unflattering woodcut portrait by Conrad Felixmüller). It presents an encoded account of a woman being held in a mental hospital (which I will say is pretty “experimental” in execution). Marcel Béalu’s novella The Impersonal Adventure, which will continue our exploration of French-language fantastical fiction; the first translation of Gérard de Nerval’s The Illuminated, an eccentric portrait gallery of eccentrics and visionaries. I read in French so a lot of authors in the pipeline are from that language: Max Jacob, Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud, Gaston de Pawlowski, Charles Cros, Philippe Soupault…

For the reason I mentioned above, I should probably steer clear of wish lists: I don’t have the resources for more than what we’ve been doing, and I am realizing I probably need to leave some things by the wayside. Such as a series of autobiographies (or biographies by known writers as opposed to “official” biographers) of “people of interest,” which I would have liked to launch with the autobiography of my publisher-hero, Eric Losfeld. Or a series of visually oriented books (literary photo-romans, surrealist graphic novels, etc.) Or a series of “missing pieces” in philosophy, which I would have liked to have started with Charles Fourier’s The New Amorous World or Peter Wessel Zapff’s On the Tragic; but the scope of such undertakings would quickly put Wakefield under, financially and otherwise…

Brief Lives of Idiots

Brief Lives of Idiots

By Ermanno Cavazzoni (Jamie Richards, translator)

Modeled after the medieval Lives of Saints, Brief Lives of Idiots devotes 31 chapters to persons of exemplary idiocy. (Generally, one person per day but three of the days are devoted to aggregates of “working,” “collateral,” and “near” suicides.) Brief Lives rekindles hope in a return to times when idiocy was kinder, gentler, almost pure in its lack of guile—idiocy straight up. Here we find a Marxist who thinks Jesus was an alien; there, a fellow who walks around the countryside offering free blood-pressure tests because he believes that blood pressure gauges have healing powers; another no longer recognizes his family, but since they leave him alone, and the woman even makes him meals, he decides to say nothing. Women idiots roam this planet, too, of course, including one who sits looking out her window as she sews, imagining that the passersby below insult her as they walk by, yet remaining deaf to the compliments her employer pays to the quality of her work.

The cynicism is sunny, and the idiots (largely) harmless cranks with (usually nonfatal) obsessions.

Interview with the translator, Jamie Richards:

TB: What attracted you to Cavazzoni’s book?

JR: I began reading Ermanno Cavazzoni many years ago and was drawn to the strangeness and humor of his work, and the way it evokes and parodies the past. In holding nothing sacred, everything becomes sacred. His first novel was the basis for Federico Fellini’s last film, The Voice of the Moon, which shows us a constitutionally wonderstruck Roberto Benigni soliloquizing into wells, at graves, or to the moon. I like Cavazzoni’s exploration of lunacy, of marginal subjects and curiosities.

TB: What in your translation do you hope comes across that you particularly liked in the original?

JR: What I appreciated in the original was the understatedness of the language and the way that its very deadpan tone managed to convey a kind of cosmic, bleak hilarity. Everything is surface, everything is in the language. I hope I was successful with the puns I had to create for “The Failed Whore” in particular, a story that required a degree of acrobatics not only to come up with new puns but also ones that matched the physical gestures accompanying them, a kind of verbal slapstick.

TB: Apart from 31 chapters for each day of a month, what in the novel is in the tradition of OpLePo / OuLiPo, and did it pose a challenge for translation?

JR: The Italian “OpLePo” is more of a loose affiliation, especially now, but it can be a useful category for describing writers who pay particular attention to literary form and structure. In Idiots the structure is made plain: based on hagiography, we have an idiography, and instead of a one for every day of the year, we have one month’s worth, punctuated by idiot suicides on Sundays (the day of rest, after all!).

TB: Who are Cavazzoni’s influences, and what else would you recommend a person read who enjoys Brief Lives?

JR: Cavazzoni counts among his influences the Renaissance poet Ariosto, Giacomo Leopardi, and Italo Calvino. Among contemporary Italians in a similar vein, I’d recommend Stefano Benni and Gianni Celati, if you can find them in English, and Nanni Balestrini’s Tristano. Or, if you haven’t read them, Gogol and Kharms.

TB: Do you have other translations in the works?

JR: I translate a lot of comics—and have graphic novels forthcoming by Gipi, Manuele Fior, and Massimo Mattioli—but I’d like to do more comic fiction. Currently, I’m working on the memoir Down the Square No One’s There by Dolores Prato and the experimental novel The Hunger of Women by Marosia Castaldi.

TB: Website for translator and editor Jamie Richards.

Psychology of the Rich Aunt

Psychology of the Rich Aunt

By Erich Mühsam (Erik Butler, translator)

Once upon a time, when families were larger and women’s lives were more circumscribed than now, the category of “Rich Aunt” arose. (Mühsam’s book was originally published in 1905.) Spinster or widow, these were women who—according to Erich Mühsam’s taxonomy—were assumed to by avaricious kin to possess enormous fortunes that would surely all be theirs one day. The psychology of the rich aunt depends equally upon the psychology of the (non-) deserving nephews and nieces, who often do what they can to speed up the mortality process in the wretched beast they would otherwise have nothing to do with, in order to pay off bills they have accumulated in anticipation of future riches. In other words, the 25 profiles of rich aunts, alphabetically arranged, serve as a catalog of schadenfreude for readers.

Interview with the translator, Erik Butler

Given Mühsam’s reputation as a satirist, how did you choose PotRA to translate as opposed to his other works?

EB:The book’s short and punchy. Mühsam really held radical views, and the quick pace lets him get away with some pretty outrageous stuff without ranting or sermonizing. There’s also an element of self-deprecation that I appreciate. It’s a bit like a cabaret performance or stand-up.

TB: I’m not sure the category of “rich aunt” exists anymore, or at least to the extent it occurred during Mühsam’s life. In England at least, and for a long time, women of any station in life were not allowed to inherit estates. What was the economic status of women at the time PotRA was written? Are there cultural implications in the book that might be lost on readers unfamiliar with the social status of German woman, circa 1900?

EB: I’m not sure how much of a reality the “rich aunt” was, even in Mühsam’s day. I think he was looking for, and found, a clever conceit for highlighting the absurdity and injustice of property relations, the law, and various institutions (especially the family). Each aunt is a caricature, and everybody after her money acts cartoonishly. The details Mühsam includes are historically and culturally specific, but they make the proceedings more vivid and engaging. The kind of antics people get up to will hardly strike twenty-first-century readers as foreign or out-of-date.

TB: What in your translation do you hope comes across that you particularly liked in the original?

EB: The author’s talent for unflattering portraits that still manage to capture human pathos; his knack for conveying gravity in farcical situations.

TB: Who are Mühsam’s influences, and what else would you recommend a person read who enjoys Psychology?

EB: Karl Marx was a brilliant satirist and master of put-downs. If you read him for style, you’ll see his influence on Mühsam. His contemporary and friend Heinrich Heine is also an important point of reference—another German-Jewish writer who turned deep disaffection into biting wit. Among Mühsam’s contemporaries, I’d recommend Salomo Friedlaender and Oskar Panizza (conveniently published by Wakefield!), as well as Karl Kraus and Kurt Tucholsky.

TB: What other translations in the works do you have?

EB: I’ve been hoping, for some time now, to translate a few works by Jean-Pierre Brisset. He was a (largely) mild-mannered railroad employee who came up with a grand theory of human origins and religion based on puns. Among other things, he claimed that the Roman Catholic Church invented Latin to retain a monopoly on the Bible and that we’re descended from frogs. He also devised a method to teach people how to swim on land.

TB: In addition to Erik Butler’s translations, he’s also most recently written The Devil and His Advocates “Written in the spirit of Mühsam and other crackpots I admire,” says Butler.

The Great Nocturnal: Tales of Dread

The Great Nocturnal: Tales of Dread

By Jean Ray (Scott Nicolay, trans.)

A Belgian writer of eerie stories in the tradition of Poe, some of Jean Ray’s stories were translated into English during the 1930s and published in such pulp treasures as Weird Tales. In workman-like fashion, he cranked out and published stories by the dozens, under varieties of pseudonyms. Thanks to the efforts and Wakefield Press and translator Scott Nicolay, Ray’s oeuvre is being represented by fresh translations, new editions, and (I believe) a complete edition.

Although Nicolay believes that Nocturnal is not Ray’s strongest work, he also believes it is his most consistently representative of Ray’s themes and methods. An excellent afterward sets the stories in this collection within the context of his other works, pointing out the interrelationships among character, incident, and place.

The stories aim to stir unease within readers, anxiety and fear of the loathsome and morally wrong. Ninety years later, the dread may be less palpable, but the stories are still fun to read. The story telling is ardent but not over-the-top, and Nicolay’s translation uses contemporary (but not anachronistic) idioms, keeping the language fresh and easy to engage with.

Interview with the translator, Scott Nicolay

TB: Something that I thought came through in your translation was Jean Ray’s joy of telling a story—perhaps it was the settings and pacing. Which characteristic(s) of Ray’s storytelling were you trying to convey with your translation?

SN: If that was a major takeaway for you from reading these translations, then I am very happy, as that joy is much of what I wanted to share with English-language readers. When my friend John Pelan first sent me his beater copy of Ghouls in My Grave and turned me on to Jean Ray back in the ’90s, I was immediately and profoundly affected by what struck me as the freshness of the writing—even though I was reading thirty-year-old translations of sixty-year-old stories. The writing felt fresh in a timeless way. Not too many authors have that power. The only similar experience that comes to readily to mind was my first encounter with Charles Willeford’s fiction a few years earlier. Or first reading Alistair Rennie’s story “The Gutter Sees the Light that Never Shines” in The New Weird. Aickman maybe. Some of the credit for the impression Jean Ray had on me must go to Lowell Bair, who translated those stories. When I began my own translations, Bair’s work was my yardstick for capturing that quality. I felt he gave Jean Ray a voice in English that read like Jim Thompson channeling Poe, each at their best. And once I’d read the original French, that seemed spot on to me, at least for 1964. I haven’t deliberately gone after the same thing with my translations, this being a different time, but my goal has been something comparable.

As a storyteller, Jean Ray was almost a force of nature. Although his biographical deals have been infamously muddled, we have long known that he could write at a pace that approached automatic writing. Sitting at the typewriter, he became something close to the teletype operator in H.F. Arnold’s classic weird story “The Night Wire,” who types a different story with each hand and continues to type even after his death. My mental image of him is this sinister guy who emerges from the darkness at the end of the bar offering to tell you a story if you buy him some whiskey—good whiskey—and keep it coming. And once he’s had that first whiskey, buckle your seatbelt. This was a man who lived to tell stories. That something that always comes through from his work.

Take “The Mainz Psalter” for example. I think that novella has gotten enough attention in English now that a significant audience recognizes it as one of the essential texts in weird fiction. It’s often compared to Lovecraft and Hodgson, for obvious reasons—and it definitely cribs a bit from Hodgson’s The Ghost Pirates, and possibly also from Lovecraft and even H.G. Wells—but it’s a far wilder story than any of them could have written. That may be a bold claim for me to make, but I dare anyone who’s read it to disagree. It’s simultaneously pulpy and beautifully written. The title, which is the name of a legendary incunabulum, suggests a narrative along the lines of an M.R. James story, so the reader is caught unawares. Early on we get a whole page of Dickens references (something mysteriously missing from Bair’s version … and then we’re off on a bonkers bazonkers high seas adventure that reads far more like Robert E. Howard at his greatest then any of the writers mentioned above. The story is a literary rollercoaster ride. It’s sheer joy for the reader and I can’t help but believe Jean Ray must have had a blast writing it—in Ghent’s Nieuwe Wandeling prison, a hellhole straight out of Foucault.

TB: Parallel to your work as a translator is a successful career as a writer of fantasy and weird stories, for which you won a World Fantasy Award. How has translation affected your own writing? I’m thinking both of your translations of weird fiction in general and close work with a single author in particular. When you’re working that closely with the mechanism of storytelling, what do you learn about the medium? Your afterward to Nocturnal is a model of close-reading scholarship.

SN: Jean Ray has been a major influence on my fiction from the start, although that may not always be obvious. Much of what I take from him is the central concept of his weird fiction, the emphasis on the interaction between the “intercalary worlds” and our own. My most recent novella, the capper of my second collection, is all about that, from the intimate perspective of a single salamander to a vast intergalactic scale. Beyond that, I think I aim to capture some of that freshness and immediacy of his work, and the vividness of the settings. There is often a claustrophobia to his settings as well, and I think that is something my work shares in, though that may be natural on my part (not that I am claustrophobic: as a caver, I am exactly the opposite).

Translating is a process equivalent to but different from writing my own work. Whether I am writing or translating, if it’s going well, I feel plugged in to what Jack Spicer called “the Martian.” The difference is that with translating I can in certain ways lose myself even more deeply in the process. So deeply that it becomes difficult to shake some of Jean Ray’s settings. A doomed part of my soul lives forever in the Berlin of “Mondschein-Dampfer,” for instance.

Then of course, there is the attention to detail. Only Steely Dan lyrics come close to mentioning as wide an array of alcoholic beverages as Jean Ray. Brand names become demonic invocations. And the descriptions of food… Although I think I apply this approach to other kinds of detail in my work more than for drinks or food.

TB: Who were Jean Ray’s influences and contemporaries that readers might want to pursue after reading Ray’s works?

SN: Obviously all the other authors from the Belgian School of the Strange. In addition to the four Jean Ray volumes (with more to come), Wakefield Press has also published excellent translations of collections by Marcel Brion and Michel de Ghelderode. Edward Gauvin has translated stories by a number of these authors, many of them available online, and he is simply one of the finest translators working today. One of my favorites from the Belgian School is Anne Richter, who is still alive today. Alice B. Toklas translated her first collection into English. She also edited some interesting anthologies in French, most notably perhaps Le Fantastique Féminin d’Ann Radcliffe à Patricia Highsmith (The Feminine Fantastic from Ann Radcliffe to Patricia Highsmith). That was the volume that taught me to recognize the weirdness in Virginia Woolf. Claude Seignolle only died a couple years ago, at the age of 101. A few translations of his work into English exist, but none are in print.

SN: Obviously all the other authors from the Belgian School of the Strange. In addition to the four Jean Ray volumes (with more to come), Wakefield Press has also published excellent translations of collections by Marcel Brion and Michel de Ghelderode. Edward Gauvin has translated stories by a number of these authors, many of them available online, and he is simply one of the finest translators working today. One of my favorites from the Belgian School is Anne Richter, who is still alive today. Alice B. Toklas translated her first collection into English. She also edited some interesting anthologies in French, most notably perhaps Le Fantastique Féminin d’Ann Radcliffe à Patricia Highsmith (The Feminine Fantastic from Ann Radcliffe to Patricia Highsmith). That was the volume that taught me to recognize the weirdness in Virginia Woolf. Claude Seignolle only died a couple years ago, at the age of 101. A few translations of his work into English exist, but none are in print.

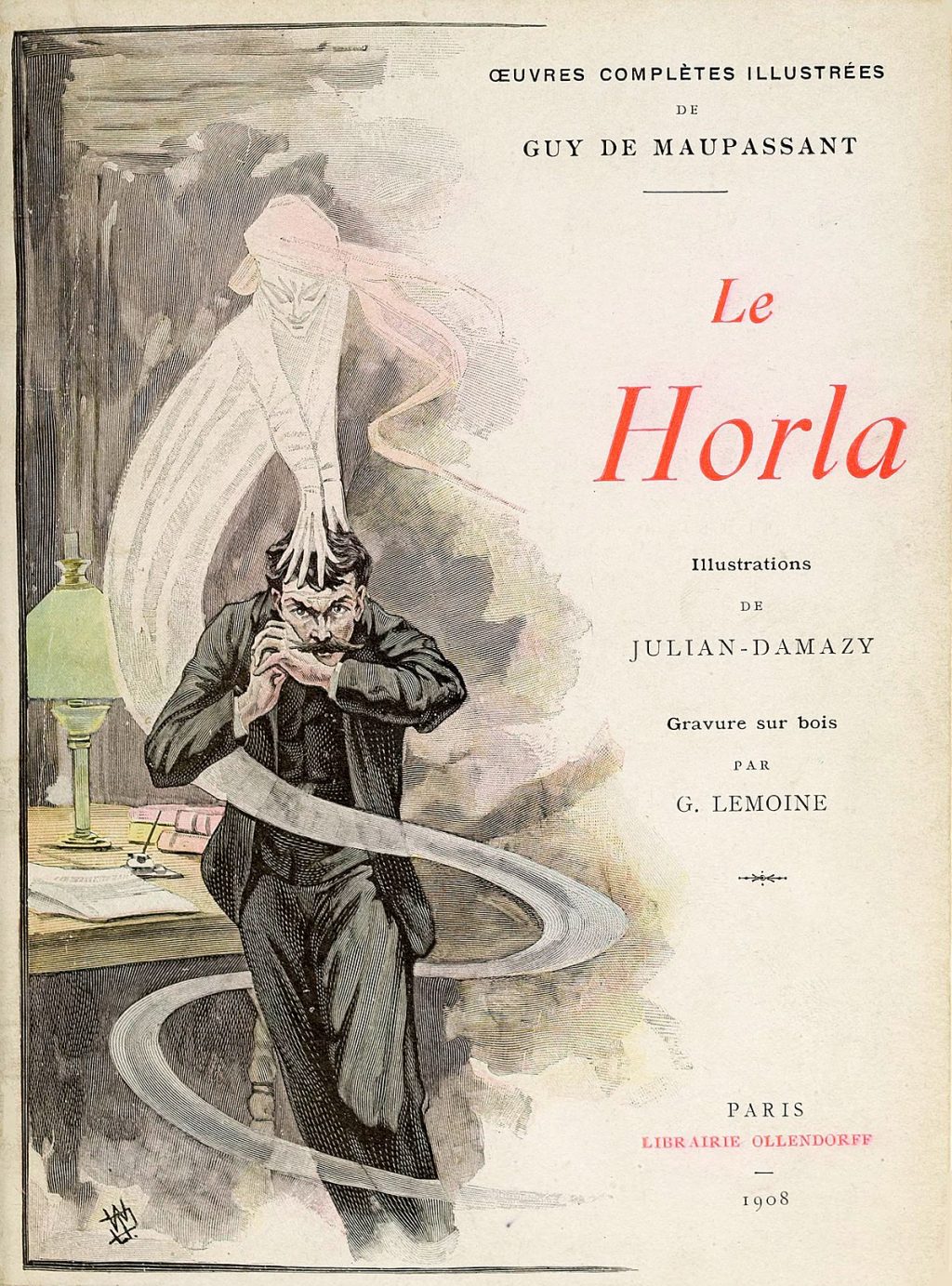

As far as influences, more people in the Anglophone world should read Guy de Maupassant. He was one of the great short story writers and I don’t feel like he gets his due anymore. I was lucky enough to encounter him as a child thanks to CBS Radio Mystery Theater’s adaptations of “The Horla” and “The Hand.” Both these stories were clearly important to Jean Ray. And then of course there is Ray’s fellow Belgian (and mentor) J.-H. Rosny. Rosny was actually two brothers writing under one name. If you know of them, it’s probably because of the wonderful 1981 film The Quest for Fire with Ron Perlman and Rae Dawn Chong, which was an adaptation of Rosny’s prehistoric novel La Guerre du Feu. A few years ago I translated the deeply weird novella Les Xipéhuz for Dim Shores Press, although this one was probably written only by the older brother “Rosny aîné.”

TB: What about this style of storytelling appeals to you? How do you keep fresh the joy of imagining weird worlds and provoking anxieties?

SN: To me the world really is weird. Deeply weird. Yet I struggle to see the places where this weirdness shows through. I’ve spent decades contemplating the vastness of the universe and my own—our own—insignificance within it. But where in our lives do we encounter the truly weird, the genuinely other? The signs are missing, at least on our plane. Writing weird fiction, or translating the work of a weird master like Jean Ray, puts me in the world as I believe it exists—somewhere. As terrible as the worlds of weird fiction are, they offer a glimpse of the genuinely awesome that we are missing today in a world where people are so eager to discard reality in order to believe the stupidest and most ridiculous things.

TB: What other projects are you working on now?

SN: I finished my second fiction collection, And at My Back I Always Hear, a few months ago. It’s currently with a publisher who had expressed interest after my first collection. And of course there’s my dissertation research on Mimbres Cave Ritual, which has to be my priority right now. I also finished editing another work of the heart, Research into Marginal Living: The Selected Stories of John D. Keefauver, which should be out soon from Lethe Press. Keefauver is another writer who wrote almost entirely short fiction and who deserves to be better known. I’ve been a fan of his work since the ’70s. I connected with him a couple years before he died and have been working with his family on this volume for several years. Beyond that, gardening, canning, cooking. And I hope to get back out into the field and map some caves this summer. The entire discipline of archaeology lost a year of fieldwork due to the pandemic. Other groups have had it worse, of course, but it was still a great loss, and a wrench in the works of my research.

TB: Scott Nicolay’s website is www.scottnicolay.com. ![]()

Micro-reviews of other Wakefield titles

Paul Sheerbart: The Perpetual Motion Machine: The Story of an Invention (Andrew Joron, translator) and Rakkóx the Billionaire & The Great Race (W.C. Bamberger, translator; Félix Vallotton, illustrator): It would be an exaggeration to call Scheerbart the Ed Wood of invention—he only tried inventing one machine, after all. But the enthusiasm and positive spirit with which he approached his project is on par with Wood’s guileless cheer, as is his certainty in the inherit wonderfulness of his project. Scheerbart took his perpetual motion machine through 26 iterations over two-and-a-half years, yet most of this slim account is devoted to, not the work involved in making the machine and the tests undertaken to prove its worthiness, but the various and wonderful ways in which his machine will improve the world—the assumed result of his untried idea. Although Scheerbart never seems entirely serious about his project—he boldly declares his ignorance of physics as a factor in his favor—he nonetheless states repeatedly that the idea and the plans he drew up for it bordered on a single-minded mania.

Paul Sheerbart: The Perpetual Motion Machine: The Story of an Invention (Andrew Joron, translator) and Rakkóx the Billionaire & The Great Race (W.C. Bamberger, translator; Félix Vallotton, illustrator): It would be an exaggeration to call Scheerbart the Ed Wood of invention—he only tried inventing one machine, after all. But the enthusiasm and positive spirit with which he approached his project is on par with Wood’s guileless cheer, as is his certainty in the inherit wonderfulness of his project. Scheerbart took his perpetual motion machine through 26 iterations over two-and-a-half years, yet most of this slim account is devoted to, not the work involved in making the machine and the tests undertaken to prove its worthiness, but the various and wonderful ways in which his machine will improve the world—the assumed result of his untried idea. Although Scheerbart never seems entirely serious about his project—he boldly declares his ignorance of physics as a factor in his favor—he nonetheless states repeatedly that the idea and the plans he drew up for it bordered on a single-minded mania.

Did William Burroughs ever read Scheerbart? “The Great Race” (the stronger of Rakkóx the Billionaire & The Great Race) anticipates by 60 years some of the motifs that occupy some of Burroughs work, especially within his cut-up trilogy (i.e., The Soft Machine, The Ticket That Exploded, and Nova Express). Subtract the drugs and homoeroticism and you’re left with mugwumps, human-sized centipedes and scorpions, and battles between control and freedom. Replace Burroughs’s centipedes and scorpions with newts and worms, and the effect is pretty similar. From the back jacket: “‘The Great Race’ . . . describes an intergalactic competition among worm spirits who wish to separate from their stars and achieve true autonomy. . .” In each story, Scheerbart focuses more on description than motivation. As a result the stories have a static quality.

Gabrielle Wittkop: The Necrophiliac (Don Bapst, translator) and Murder Most Serene (Louise Lalaurie, translator): I can’t say it’s to the liberal-minded credit of Lucien—the eponymous narrator of The Necrophiliac—that his urges are not dissuaded by age, gender, or disability; and his enthusiasms can be comic, although I don’t know if that was Wittkop’s intention. But really, how seriously can one take the urges of a necrophiliac? Still, Wittkop writes with a restrained hand, and as others have noted, her writing is lyrical. I think it’s interesting—although I don’t know what to make of it—that a story of necrophilia was written by a woman, which, like tales of incest, are usually told and written by men. . . A deft translation by Don Bapst, who conveys the steady rhetorical register of a person of refined taste (requisite in tales of decadent debauchery), without sounding prissy or affected. . . Lucien even manages to fuck a hunchbacked midget that had been run over by a car. Just his luck: she was a virgin, too.

Gabrielle Wittkop: The Necrophiliac (Don Bapst, translator) and Murder Most Serene (Louise Lalaurie, translator): I can’t say it’s to the liberal-minded credit of Lucien—the eponymous narrator of The Necrophiliac—that his urges are not dissuaded by age, gender, or disability; and his enthusiasms can be comic, although I don’t know if that was Wittkop’s intention. But really, how seriously can one take the urges of a necrophiliac? Still, Wittkop writes with a restrained hand, and as others have noted, her writing is lyrical. I think it’s interesting—although I don’t know what to make of it—that a story of necrophilia was written by a woman, which, like tales of incest, are usually told and written by men. . . A deft translation by Don Bapst, who conveys the steady rhetorical register of a person of refined taste (requisite in tales of decadent debauchery), without sounding prissy or affected. . . Lucien even manages to fuck a hunchbacked midget that had been run over by a car. Just his luck: she was a virgin, too.

Murder Most Serene takes us to 18th-century Venice, meaning poisonings, rampant diseases, pestilent miasmas, grotesque human deformities, cabals, vermin, and flies. Despite these charms, less compelling than Wittkop’s novel about a bi-sexual, pedo-necrophilac, The Necrophiliac.

Pierre Louÿs: Pybrac (Toyen, illustrations) and The Young Girl’s Handbook of Good Manners for Use in Educational Establishments (Geoffrey Longnecker, translator): Pybrac consists of no-holes-barred debauchery described across 300+ quatrains (of an original 2,000), for which Louÿs provides endless permutations of place, manner, and means, limited only by the number of serviceable orifices in the human body. (The remaining quatrains unpublished here were auctioned off in 1936 and haven’t been seen since.) Not for the squeamish or self-righteous. Brilliantly devoid of redeeming social value.

Pierre Louÿs: Pybrac (Toyen, illustrations) and The Young Girl’s Handbook of Good Manners for Use in Educational Establishments (Geoffrey Longnecker, translator): Pybrac consists of no-holes-barred debauchery described across 300+ quatrains (of an original 2,000), for which Louÿs provides endless permutations of place, manner, and means, limited only by the number of serviceable orifices in the human body. (The remaining quatrains unpublished here were auctioned off in 1936 and haven’t been seen since.) Not for the squeamish or self-righteous. Brilliantly devoid of redeeming social value.

Suffice it to say that such an author would be unlikely to produce a less lewd book, especially as related to “young girls” and “good manners.” Funny and obscene—the kind of thing you’ll like, if you like that kind of thing.

The Table by Francis Ponge (Colombina Zamponi, translator): A meditation on the humble table, or at least the tables in Ponge’s life; a meditation what it means to be a table, to have a table, to use a table. (OK, that doesn’t sound too compelling, right? Leave it to the avant-garde to make it interesting.) Some favorite passages: “Silence is the sand of noise.” . . . tables are “soil for the pen.” . . . “The table, my console and consoler, as it is recalled to my body and at the same time my mind its notion. . . It isn’t on the metaphysical our morals rest: only on the physical.”

A Terrace in Rome by Pascal Quignard (Douglas J. Penick and Charles Ré, translators): A poetically terse story of a 17th-century engraver whose face is badly disfigured when a jealous fiancé throws acid in his face. Now ugly and rejected by the woman he loved, the engraver, Geoffroy Meaume, travels Europe plying his trade, never able to settle in any one place for long (presumably because of his disfigurement, not for a lack a talent, with which he’s richly endowed). The story is as simple and poignant as the engravings described to us.

Treatise on Modern Stimulants by Honoré de Balzac (Kassy Hayden, translator; Pierre Alechinsky, illustrator): Another in a series of short- to mid-sized essays and fictions from famous and forgotten authors, works now obscure that serve to illustrate—as the Treatise’s translator, Kassy Hayden, points out—observations on various topics from an era’s most articulate and insightful writers (such as, in this case, on coffee, sugar, and tobacco) that reveal its “history, language, culture, science and medicine, gastronomy, . . . and politics.”

The Pig: In Poetic, Mythological, and Moral-Historical Perspective by Oskar Panizza (Erik Butler, translator): The Pig catalogs quotations—from a wide variety of peoples and nations—exemplifying Panizza’s thesis that pigs have played crucial roles in world religions, bad and good (or as “opposition”—often in simultaneous, contradictory ways). The Pig itself exemplifies a time when philology held sway in the humanities, a field that drew large conclusions about humanity based upon the history if its languages.

The Hierarchies of Cuckoldry and Bankruptcy by Charles Fourier (Geoffrey Longnecker, translator): Mathematician Charles Fourier’s eccentric taxonomy of two of civilization’s better-known hypocrisies: cuckoldry and bankruptcy, the latter far worse than the former, in Fourier’s estimation, and as relevant today as when he railed against bankruptcy 200 years ago. Nicely translated by Geoffrey Longnecker.

The High-Life by Jean-Pierre Martinet (Henry Vale, translator): A perfect gem of nuttiness, misanthropy, and neurotic self-doubt, portraying a narrator who goes mad as his tale goes on. Oh, those French! Smoothly translated by Henry Vale, who re-creates Martinet’s story with faultless idiomatic English.

An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris by Georges Perec (Marc Lowenthal, translator): Perec turns a catalog into a poem: descriptions of a town square from a variety of locations, times of day, and days of the week.

The Unruly Bridal Bed and Other Grotesques by Mynona (W.C. Bamberger, translator): A brief collection of German Absurdist tales which can read like Poe and Lovecraft meet Laurel and Hardy.

A Dilemma by Joris-Karl Huysmans (Justin Vicari, translator): A nice bit of bourgeois cynical cruelty, in the French manner.![]()

Thank you for this wonderful set of reviews and appreciation of a superb and courageous press.

Hi Douglas,

Thank you for your kind note. I’ve just spoken to the author Tom Bowden who expressed his thanks.

Best wishes,

Cary Loren c/o Book Beat