Animalia

Animalia

By Jean-Baptiste Del Amo (Frank Wynne, translator)

Brutal and beautiful, Animalia depicts four generations of a farm family in France, and the Faulknerian arc of their fate from agricultural peasants to lower-class pig farmers, from the late 19th– to late 20th centuries. This family saga presents a past that is both unsentimental and unhygienic. The premise book’s premise, humanity = bestiality, is relentlessly catalogued, with illustrative metaphors throughout. The equation only becomes so when love is subtracted from humanity. How loves becomes subtracted is something the novel demonstrates via a family piggery, and the human cost of starting the piggery makes up the first part of the book.

Del Amo’s prose, in Frank Wynne’s deft translation, focuses on monosyllabic nouns and verbs, rarely adorned by adjectives and adverbs: its sentences punch in rounds of two or three dozen words at a time. The images blend and blur animal and human behaviors, parts, and secretions into a seamless and unseemly whole.

Joël is one of the sons at the end of the family line. A young man who hates the brutal, degrading work of raising pigs, Joël also resents his brutal, degrading father, and resents feeling guilty for his attraction to men, whom he encounters only in other degrading, unsanitary sites. In the following passage, Joël is shown performing one of his daily duties in the piggery, while thinking about random men and his father:

“Joël shoots back the bolt and steps into the pen. The pigs scurry towards the far railing, leaving one sow that struggles to its feet, then goes over to blend into the herd. A purulent whitish discharge trickles from her vulva, down her hocks, forming a pool on the concrete floor in which the aborted foetuses lie, small sacs of pink, blood-smeared skin with undeveloped limbs, some still encased in the placenta like – half-hard dicks in latex condoms – formless things, neither human nor animal. . .

“Perhaps the father’s contempt for him is merited: Joël has never proved himself to be good at anything and would never have been able to make a life for himself beyond his supervision.”

The abuse and degradation are shared among the men and women, although the novel focuses more on toxic masculine implosion. If job success requires you to turn off your thoughts and emotions about the animals you, with your own hands, castrate, kill, abort, beat, probe, cage, and have forcibly fucked, it will mark you. And if your family does that job generation after generation, well, something’s gotta give.

Mercy Athena

Mercy Athena

By Andrea Applebee with illustrations by Lorna McIntosh

Sylph Editions / The Cahiers Series

Moving to Greece—whose language she barely knows—after the end of a 10-year marriage, Andrea Applebee took little with her other than Mercedes Athena, her seeing-eye dog, which Applebee has become increasingly dependent upon as the degenerative eye disease she and her twin sister were born with reduces her vision to recognizing swaths of color, such as the sky. This graceful essay is coupled with illustrations (i.e., “works on paper”) by Lorna McIntosh that reflect the essay’s changing moods.

Applebee learns to navigate a new language, a new physical terrain, and new work, with Mercy as her constant guide and helpmate. They will love and rely each other for 15 or 16 years, and then Applebee’s blindness will compel her into another such relationship. She knows that about their future, but less about her own, except which of her capabilities she’s already demonstrated to herself that she can build upon.

Avian

Avian

Neel Mukherjee, with paintings by Lu Chao

Sylph Editions / Cahiers Series

A young girl, immensely intelligent, takes an interest in bird song. By the time she is 21, she has a PhD in neurology and publishes paper after ground-breaking paper on avian communication. At some point, the engrossing hobby has become a career that is engrossing to the point of excluding and neglecting her children and husband. The social services are called in, a divorce follows, her work divorces itself from reality, and her pursuit of understanding communication continues—until, perhaps, she solves the mystery of a children’s story that has haunted her all her life. Lu Chao’s paintings (executed apart from the story) complement the mood of this complex, beautifully rendered tale.

Falstaff: Apotheosis

Falstaff: Apotheosis

By Pierre Senges (Jacob Siefring, trans.)

Sublunary Editions

A tongue-in-cheek meditation on the significance of Falstaff’s feigned death in Henry IV, Part 1:

“Acting as a dead man between two merciless duel scenes . . . provides an occasion for John Falstaff to restore the oft-maligned nap to its former glory: as such, the nap won’t be the overeater’s ignoble cowardice, it will be rife with meaning, it will be heroic. Nap will become stratagem, victory deferred, mockery and diversion, non-violent wisdom, watercolorist’s restraint, dandyish nonchalance, composure of the stoic sage, unmoving harmony with the surrounding landscape, composition and performance combined, silent role bursting through the screen, Eleusinian mystery and Orphic ritual, death’s approach, a motionless danse macbre, a trick played on death itself by adopting all its outward attributes in a parodic mode, but with the highest solemnity—and the mind-boggling marriage of clowncraft and the macabre.”

No, enjoying Falstaff does not require having read any part of Shakespeare’s Henry IV. What should be enjoyed is Senges’ ability to combine the laudatory with the bathetic to applaud cowardice as moral achievement, simultaneously meaning it and not meaning it. Translator Jacob Siefring has done well at what amounts to alternating a long wink with an arched eyebrow.

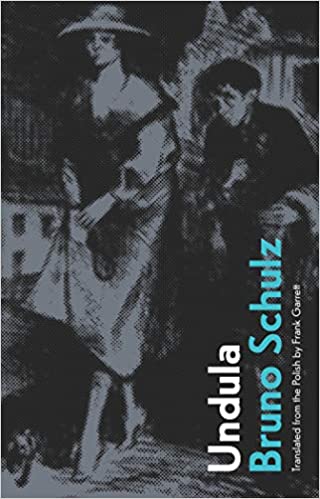

‘Undula visits the Artists’ from the ‘Book of Idolatry’, Bruno Schulz, 1920-22, 9,8 x 14,5 cm, cliché-verre

Undula

Undula

By Bruno Schulz (Frank Garrett, trans.)

Sublunary Editions

By weird alignment of the stars, an early story by Bruno Schulz was rediscovered a few years ago—perhaps Schulz’s first published story—but published (a) under a pseudonym in (b) The Journal of Petroleum Officers in Boryslav. “Undula” is an atmospheric sketch, a cross between Poe and the later Decadents, a mournful, dream-like musing over one Undula, a sort of dance-hall entertainer of easy virtue whose pure essence only the narrator sees.

But decadence requires things go wrong, and they do. The narrator realizes that, despite Undula’s degraded life, to her the narrator is nothing, which the narrator is only too eager to accept as proof of her perfection: “Now it’s time for me to return to the threshing floor from which I had left only an impetuous miscarriage. I shall follow through to the end so as to atone for being my Maker’s mistake.” The rest of the story takes us back to where it begins—in a room, alone, drifting in and out of consciousness, mulling over the homunculus that is his soul.

Follow the connection between “Undula” and The Book of Idolatry in: Buried Treasure: A New Story by Bruno Schulz Unearthed

A short lecture on Bruno Schultz by David Grossman:

Fragments from a Found Notebook

Fragments from a Found Notebook

By Mihail Sebastian (Christina Tudor-Sideri, trans.)

Sublunary Editions

An early, overlooked work by the Romanian writer Mihail Sebastian, published in 1932 when the author was 25, Fragments tries out an old literary conceit: Discovering the inner life of a stranger as revealed in a lost document (be it diary, travelogue, etc.), in this case, a cheap notebook (which says something about the author’s social standing). In many regards Fragments resembles the works of the Decadents, recounting the dissipated life of a man for whom the phrase “been there, done that” sums up the narrator’s attitude and outlook.

But 1932 was a bit late in the day for Decadence (perhaps one reason for Fragments’ lesser-known status), although it repeatedly strikes a note that resonates in the heart of many young people: being misunderstood and feeling angry about it—anger topped with feigned indifference to the world and its ways. Unlike other Decadent works I’ve read, though, this narrator has no single love (requited or un-) whose loss leaves him twisting in the wind. On the contrary, the narrator has broken the hearts of countless women immediately post-orgasm, to devote himself to mulling over his adherence to following his thoughts and emotions wherever they lead him, at whatever cost.

The End

The End

By Aditi Machado

Ugly Duckling Presse Pamphlet Series

The End begins with the end of Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo” (“You must change your life”) to explore epiphanies (literature’s “money shot”), understanding and teaching poetry, the economy (literal and metaphoric) of poetics, and what it means for a poem to end. Clear, persuasive, and engaging, this essay—implicitly on ethics—will appeal to those who read, think about, teach, and/or write poetry.

Notes on Mother Tongues: Colonialism, class, and giving what you don’t have

Notes on Mother Tongues: Colonialism, class, and giving what you don’t have

By Mirene Arsanios

Ugly Duckling Presse Pamphlet Series

About forty years ago, I was confronted for the first time by the idea that the language one spoke might be more than just a matter of “natural course,” of just getting along, of knowing the speech codes and accents that, followed, opened doors of opportunity. A language might be imposed by a conquering tribe, eagerly adopted and encouraged by the conquered who merely sought social status and material wealth, no matter who was in power. Or a language might be imposed by nation one has emigrated to, with no one around to appreciate the beauty of the lost language, especially in service to expressing its history and lore. In both cases, an ethos-expressive scar reminds the person of a loss.

James Joyce’s use of “usurper” in Ulysses triggered that realization for me. (Yes, even though the usurper in question is Buck Mulligan—as Irish as Stephen Daedalus, Joyce’s alter ego—but that’s a digression I’m avoiding.) I was shocked that a writer with the ability to make language sing actually had some resentment toward it, and that mastering it was less an act of joy than stern rebuttal to the colonial master.

A few years later, I attended a symposium of Russian immigrants to the U.S., which included Joseph Brodsky and other writers whose names I didn’t recognize at the time. Anyhow, all of the writers bemoaned the loss of an audience for the Russian language, including their children, for whom the language would be meaningless without Russian culture, too.

Identity, heritage, mastery over one’s fate—themes threaded by language. Or, in the case of Mirene Arsanios, multiple languages, histories, and cultures—including gendered expectations of what it means to be a woman in each of them, as mother, daughter, and partner.

“My language has been known to experience contradictory feelings, such as her father’s shame and his defiance of occupation, his staunch and irrevocable support of the Palestinian cause and its fight for liberation, his condemnation of Zionism when watching the news, while my language, next to him, still a child, soaked in his rage together with the uncanny realization that a same language can be both subservient and subversive and that these seemingly opposite positions can exist in a single sentence like the one my language just wrote.”

Contradictory feelings, shame and pride, and the terms in which they are expressed and why. A Chinese woman once told me that, in college, she and her friends would discuss in English topics (like sex) they found too embarrassing to discuss in Mandarin. While some of Arsanios’s linguistic habits might include such rhetoric of distancing, they also imbue her word choice with connotations and implications that double the size of her internal dictionary. While this might expand her capacity for nuance, Arsanios’s essay suggests that she feel the weight of history, complicity, and colonization taint her palette.

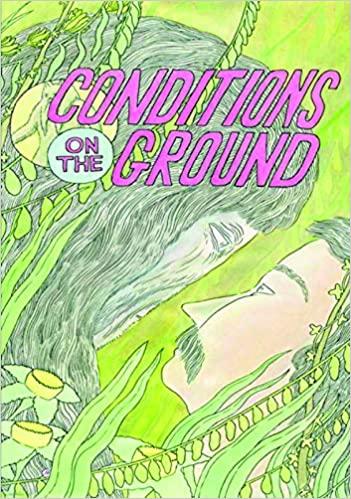

Conditions on the Ground

Conditions on the Ground

By Kevin Hooyman

Floating World Comics

The collected Conditions on the Ground zines add up to 350 pages of slice-of-life anxiety and doubt among a group of characters (not all of whom interact with other) told through vignettes and anecdotes. “Can of Shit,” though, was, for me, the piece that stood out, as one of the characters opens a can of dog food that smells, um, suspiciously bad: “It would not surprise me at all if what has happened is that someone actually took a shit in this can before they canned it up. Like at the factory some worker took a shit in one of the cans as a joke or to show off. And I just opened that fucking can.” Each passing second brings a new round of olfactory shock at just how bad the stench really is—as if the odor is worsening or the character’s ability to appreciate its horrific properties only increases—and each passing second brings the character closer to vomiting and passing out before he can reach the door to toss the can outside. This sequence and the actions that follow deserve being set to film.

![]()