Women in Concrete Poetry: 1959-1979

Women in Concrete Poetry: 1959-1979

Edited by Alex Balgiu and Mónica de la Torre

Primary Information

Using the shapes of type itself to enhance or otherwise shape textual (non)meaning and effect, instances of “concrete poetry” have occurred in art and literature over several centuries. But during the early 1950s, its popularity exploded simultaneously in South America and Western Europe, and from there the rest of the world.

Most instances of 20th-century concrete poetry were based on exploiting the capabilities of a relatively inexpensive and common mechanical tool—the typewriter—viewed it in terms of its basic components and actions—inked ribbon struck onto paper by metal keys shaped as letters and punctuation—in the service of communication. Concrete poetry often uses symbols of sounds and silences to create the unsayable as image, and thereby bridge the gap between the vocable and the visual. By “unsayable,” I mean nobody’s declaiming these poems at the local slam because doing so is either impossible or irrelevant or, most likely, both.

Women in Concrete Poetry: 1959-1979 is a 480-glossy-paged, over-size anthology with examples and excerpts by women practitioners of the genre from every continent but Antarctica. (The print quality of this anthology is no doubt far lower in pulp count than the paper the original versions of these poem were printed on.) Few of the poems are explicitly feminist or political—most of the writers (like their male counterparts who got the attention) were exploring the boundaries of concrete poetry’s semantic capabilities and the content it best conveyed, but not necessarily as gender/patriarchy boundaries to be transcended.

The anthology includes translations (at the end), biographies, and an implied promise of a follow-up anthology. An excellent honor, acknowledgment, and introduction to concrete poetry in general, as well as the women in particular who developed that genre.

From Poèmes (1959) by Suzanne Bernard

From Mot-Couleur-Roman (1970) by Annalies Klophaus

F Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry

F Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry

Edited by Galina Rymbu, Eugene Ostashevsky, and Ainsley Morse isolarii

I didn’t know then that everyone had an interest in my vagina:

the state, my parents, gynecologists, strange men,

Orthodox priests with epaulets under their robes

and women’s blood on their robes, employers, anti-extremism agents, the military, fascists, immigration cops,

banks, conservative critics of ‘depraved lifestyles,’

patriotic cultural figures, appropriators of traditional values,

washed down with brandy.

—from “My Vagina” by Galina Rymbu

F Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry is, according to its publisher, “the first-ever Russian magazine and platform dedicated to feminist and queer writing”—which is almost a moot point given the (quasi-)illegal status of Russia’s LGBQT+ communities and publications, as well as Putin’s and the Russian general public’s hostility towards sexual and gender minorities. This bi-lingual publication of a dozen of F Letter’s contributors acts to further disseminate these poems in their native language, which is otherwise difficult to do.

Although American readers may be familiar with decades of easy access to confessional poems that intersect the personal with the political, with domestic abuse, with cultural degradation of women, and so on*, the poems in F Letter are fresh, powerful, and unique, not mere Western knockoffs. One needn’t be a Westerner or a Western woman to appreciate the force, sentiment, and sanity of these poems. In an interesting political move, Russian feminists and queers have re-appropriated the term “poetess” exactly to emphasize the creation and experience represented in the poems as specifically female-gendered.

My favorite poems from this collection are “These people didn’t know my father” by Oksana Vasyakina and “My Vagina” by Galina Rymbu, co-founding editor of F Letter (F pis’o, in Russian). Galina Ryambu’s English-language translation, Life in Space (Joan Brooks, translator) comes out November from Ugly Duckling Presse

The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer

The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer

Alessandra Sanguinetti

Mack Books

Back in 2012, regarding The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and the Enigmatic Meaning of Their Dreams (2010), I wrote that “Sanguinetti’s photographs are indeed enigmatic, particularly the expressions of the girl Belinda whose reserve in these pictures, even when whimsically dressed and posed, makes her seem mature beyond her age, a young woman who seems to live primarily in her head. Her foil is her cousin, Guille, who plays Mutt to Belinda’s Jeff, the one who seems like a genuine kid in contrast. The bond between the two is apparently strong and yet mysterious.”

Ten years later, Guille and Belinda are back, Sanguinetti documenting their friendship, home, and family as they negotiate their teen years into young adulthood, then womanhood as each becomes a single parent. Sanguinetti shows more of their individual lives, as befits two young women working towards independence in rural Argentina, where they raise their children in relative poverty. Belinda’s stare is still the same: as if look for or trying to imagine her future, steeling herself for bravery in the face of the inevitable rather than hope for different.

Will this be an Argentine Seven Up! writ small? As the charm, hope, and whimsy of childhood give way to grim persistence, Sanguinetti’s photographs provide proof that beauty, love, and friendship endure.

Here is a recent and charming Zoom interview Sanguinetti held with Guille and Belinda to discuss their thoughts on the project and the photos selected to represent their lives, and other questions submitted by those familiar with the series (in Spanish with English subtitles).

Alessandra Sanguinetti, from ‘The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer’ (MACK, 2020). Courtesy the artist and MACK.

Alessandra Sanguinetti, from ‘The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer’ (MACK, 2020). Courtesy the artist and MACK.

Elegy for Joseph Cornell

Elegy for Joseph Cornell

By María Negroni (Allison A. deFreese, trans.)

Dalkey Archive Press

Mixing biography, drawings, musings, and fictions, María Negroni’s single-page/paragraph sketches form a series of prose poems analogous to Cornell’s boxes, but with Cornell himself as the subject. The book could easily be retitled 80 Ways of Looking at Joseph Cornell, each brief piece a bauble related to Cornell’s filmmaking, domestic life with a paralytic brother, ephemera collecting, and friendships with Marianne Moore, Marcel Duchamp, and Stan Brakhage. Allison deFreese render’s Negroni’s prose into limpid, idiomatic English.

Natch

Natch

By Sophia Dahlin

City Lights

Someday my punishment will come

like a hamburger skidding down

a zinc countertop.

How still we’ll be

me lollipopped on my paunchy stool

some bun stacked red with the glam of death

what was made for me is mine.

—from “I’m a Ninny”

Natch is Dahlin’s first book-length collection of poems—accessible, personal, and exuberant in their enjoyment of the body, alone and coupled. She has a knack for aphorisms, too: “the rain nips patrons from the sidewalk in” to a café, and “I can’t buy freedom / but I can denude my wishlist,” and “People couple to suffer.” I look forward to this poet’s future.

Dahlin reads for City Lights. Her part begins at about the 28-minute marks.

Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City

Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City

By Reynaldo Rivera

Semiotext(e)

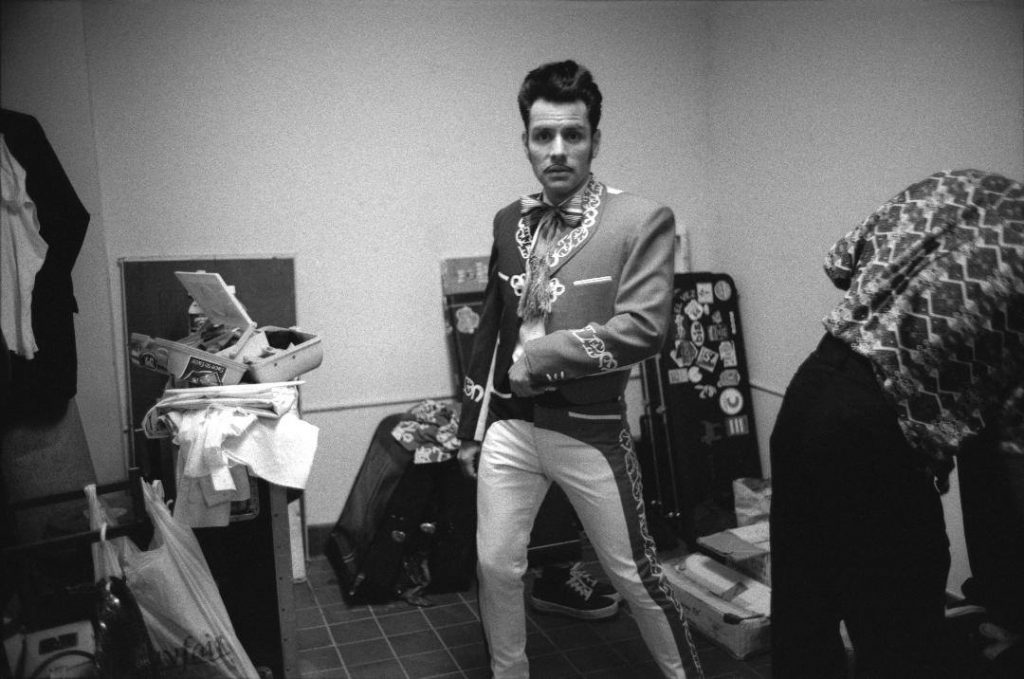

Reynaldo Rivera photographed Los Angeles’s demi-monde during the 1980s and ‘90s—a sort of counterpart to Bukowski’s LA hetero-underworld of the ‘60s and ‘70s, but instead populated by the habitués of LA’s dive gay and transvestite bars, whose performers Rivera befriended. His friendship with the performers shows in the intimacy of photos, the ease at being around the camera, the ease at being themselves among each other—all in service of producing honest documentation of a time and mood, and the people at the margins of society who managed to eke out some joy in their lives. A length dual-bio ends the book in a series of email exchanges between Rivera and Vaginal Davis.

The Party

The Party

By Tomi Unger

Fantagraphics

As we watch its scaffolding tremble, our age of the gilded fascist can take solace in knowing that we’ve been here before, and that the rest of us are right for despising the few who would convert us into servants of Moloch, desperate and blind in our search for more money and power. Growing up in Nazi-controlled France, Tomi Unger knew something about fascism and the type of people money and power tends to attract: oblivious, venal, casually cruel, and untainted scruples. The Party, originally published in 1969, is a book of Dickensian-named caricatures of wealthy, powerful, and politically connected seniors notable for—among the women—their garish lashes and sagging breasts and—among the men—obscured eyes and predatory urges. Although The Party is being republished as part of Fantagraphics’ commitment to reprinting Unger’s most important work, the timing of this reprint makes The Party also read as an expanded version of Poe’s “Masque of the Red Death.”

Now! #9: The New Comics Anthology

Now! #9: The New Comics Anthology

Edited by Eric Reynolds

Fantagraphics

Raquelle Jac’s feature contribution, “Misguided Love,” fills her pages with raw, visual energy that contributes to her story’s emotional intensity. But the story itself—earnest, heartfelt, and no doubt true—is similar to other earnest, heartfelt, and true confessional stories of awkward late bloomers (aka “the comics industry”) to an extent that the story feels familiar rather than unique.

“How Mums Annoy You” by Ethel Wolfe centers on the type of protagonist I’ve never been able to develop sympathy or empathy for: self-centered, unreflective, and unwilling to learn from personal mistakes, which therefore are predictably repeated ad nauseum throughout the idiot’s so-called life. While Wolfe tells the story via panels shaped as smart phone to convey and critique the conventions of Youtuber life, the ideal medium for this story would be on the phone itself.

Theo Ellsworth, Noah Van Sciver, and John Ohannesian do their usual things. Karen Katz, Emil Friis Ernst, and Ben Nadler—names new to me—also turn in solid contributions.

As with an anthology, results can vary, but Fantagraphics tends to maintain a pretty high standard for its various anthologies, such as Now!’s predecessor, Mome. The series editor, Eric Reynolds does a commendable job exploring the various ways of presenting visual narratives. While Jac’s and Wolfe’s stories, for instance, didn’t completely sell me, I remained impressed by their work toward extending the boundaries of the medium.