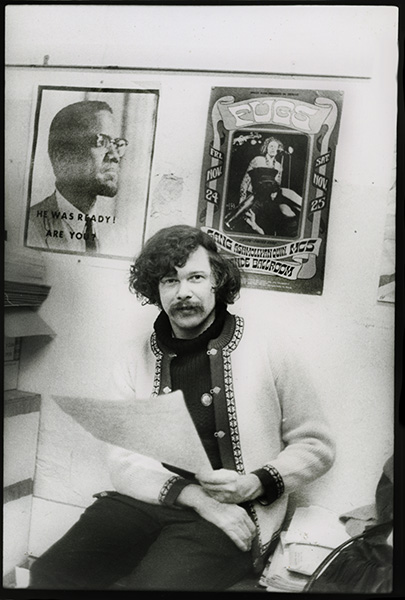

Ed Sanders at the Detroit Artists’ Workshop, photo by Leni Sinclair, 1968

A Terrible Beauty Is Born: Edward Sanders, the Techniques of Investigative Writing, and 1968

by M. L. Liebler

Being certain that they and I

But lived where motley is worn:

All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.–W. B. Yeats, “Easter 1916”

My intention is to offer readers a practical approach to Edward Sanders’s process of investigative writing and to his 1997 book 1968: A History in Verse. I offer this essay as primer and overview. For those readers expecting another stuffy academic meandering on the state of American literature in the late twentieth century, be warned from the start: there’s far too much of that crap already. Ed Sanders’s creative work as a poet, fiction writer, musician, and political activist has always been about getting closer to the truth, even if the end result should be “a terrible beauty.” Because Ed has always approached his art as a search for truth and justice, which may seem quite quirky in the weird business of contemporary American letters and postmodern theory, this essay will be straightforward rather than encoded garble meant to stump rather than lead. In order properly to inform the reader about Ed Sanders’s investigative process and its application in this book, I will first need to provide some basic background: Ed’s discovery of this unique process, the process itself, the debt owed to the great American bard Charles Olson, and the birth of investigative poetry.

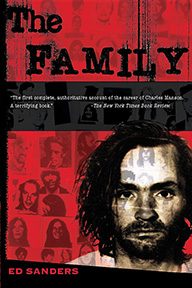

In 1970 Edward Sanders published the very first book (The Family) dealing with Charles Manson, his Family, and their horrific murders of Sharon Tate and the LaBiancas in Los Angeles, California, in 1969. These murders and the Manson Family confirmed for older Americans everything they believed to be evil and terrible about the youth culture of sixties America. Charles Manson’s vision was that a race war was coming down in America (aka “Helter Skelter”) and that the Beatles’ White Album contained the prophetic message of the evil gloom doom about to settle upon the American teenage wasteland already cluttered with Vietnam, drugs, student protests, rock `n’ roll, civil rights, and a seeming disdain for the older generation. Ed Sanders, with his intense interest in history and literature, along with his belief in Charles Olson’s concept of composition by field, gained press credentials through the Los Angeles Free Press, and he thus began to collect data through interviews, research, and a well-planned, thorough investigation. In his research he discovered the terrible reality of cult behavior in general and of youth cults in particular in sixties America. While these revelations were as startling to Ed as they were to the public at large, the investigative process drew him deeper into exploring and working exclusively with what he later called investigative poetry. During a radio interview on Detroit’s WXYT in the summer of 1997, I asked Ed if, perhaps, The Family was the beginning of his interest and work in what would later become known as investigative poetry. He paused, carefully thought a minute, and then responded that yes, he now believed that his interest in and experience with the process was indeed spawned during those difficult and strange times. But the whole story of Ed’s interest in this unique concept of writing and research goes back a bit further than 1969 and Charlie Manson.

In 1970 Edward Sanders published the very first book (The Family) dealing with Charles Manson, his Family, and their horrific murders of Sharon Tate and the LaBiancas in Los Angeles, California, in 1969. These murders and the Manson Family confirmed for older Americans everything they believed to be evil and terrible about the youth culture of sixties America. Charles Manson’s vision was that a race war was coming down in America (aka “Helter Skelter”) and that the Beatles’ White Album contained the prophetic message of the evil gloom doom about to settle upon the American teenage wasteland already cluttered with Vietnam, drugs, student protests, rock `n’ roll, civil rights, and a seeming disdain for the older generation. Ed Sanders, with his intense interest in history and literature, along with his belief in Charles Olson’s concept of composition by field, gained press credentials through the Los Angeles Free Press, and he thus began to collect data through interviews, research, and a well-planned, thorough investigation. In his research he discovered the terrible reality of cult behavior in general and of youth cults in particular in sixties America. While these revelations were as startling to Ed as they were to the public at large, the investigative process drew him deeper into exploring and working exclusively with what he later called investigative poetry. During a radio interview on Detroit’s WXYT in the summer of 1997, I asked Ed if, perhaps, The Family was the beginning of his interest and work in what would later become known as investigative poetry. He paused, carefully thought a minute, and then responded that yes, he now believed that his interest in and experience with the process was indeed spawned during those difficult and strange times. But the whole story of Ed’s interest in this unique concept of writing and research goes back a bit further than 1969 and Charlie Manson.

In 1950 humdrum, strait-laced, post-World-War-II America, Charles Olson, controversial American poet and critic from Gloucester, Maine, wrote perhaps one of the most famous and challenging essays on contemporary American poetics, entitled “Projective Verse.” This mind-expanding essay has moments of great insight and clarity, and these moments wholly inspired a young Midwestern boy, who had been raised in suburban Kansas City, to delve more deeply into the essay’s meaning and to bring further focus to its application. Olson believed at the time that if poetry and poetics were to change, advance, and remain vital in American culture and art, then each area (poetry and poetics) must “catch up and put into itself certain laws and possibilities of the breath, of the breathing of the man who writes as well as of his listenings (The revolution of the ear …)” (Olson 15). Olson then advocated that contemporary poets consider working “OPEN, or what can also be called COMPOSITION BY FIELD, as opposed to inherited line, stanza, over-all form, what is the `old’ base of the non-projective” (Olson 16). Olson stated that there were three important aspects of this new style of writing:

°The Kinetics: “A poem is energy transferred from where the poet got it … by way of the poem itself to … the reader.”

° The Principle: “Form is never more than an extension of content.”

°The Process: “One perception must immediately and directly lead to a further perception.” (Olson 16-17)

Olson then concluded this section of his essay by stating, “So there we are, fast, there’s the dogma. And its excuse, its usableness, in practice. Which gets us, it ought to get us, inside the machinery, now, 1950, of how projective verse is made” (Olson 17). For Charles Olson, it was all that easy and that difficult, but it is this basic concept and its subsequent theory that attracted the attention of young Ed Sanders, who then began his journey on the road to furthering Olson’s theory and, eventually, to creating his own style of investigative writing.

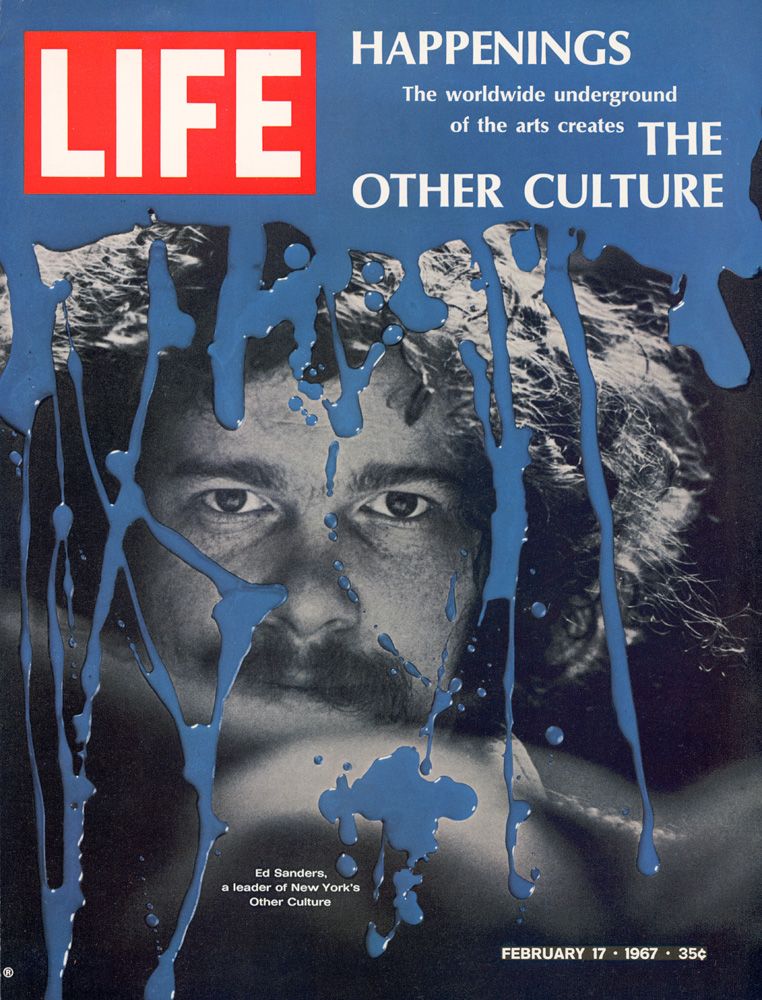

At this point I think it important to mention a bit about the type of writer and artist Ed Sanders was and continues to be. After leaving Kansas City immediately upon graduation from high school, Ed split the Midwest for New York City, where he determined to become a poet. Ed had been inspired first by Allen Ginsberg’s legendary poem “Howl” and such Beat generation writers as Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, and Gregory Corso in addition to Charles Olson. The brief overview of Sanders’s history is that he attended New York University as a student of Greek and Latin, opened the now historically famous Lower East Side Peace Eye bookstore, started up and edited Fuck You / A Magazine of the Arts, and shortly thereafter formed, with New York City poet and artist Tuli Kupferberg, the art-rock group the Fugs in 1964. The Fugs took their name from a fornicatory euphemism in Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead. The Fugs became quite popular on the mid-sixties Greenwich Village cultural scene with their several-times-a-week performances of poetry, storytelling, and rock music at the Playhouse Theater on Astor Place. Word spread around Manhattan about this group’s sold-out performances, and soon the Fugs were offered a major recording contract. This was the beginning of Ed’s rock `n’ roll career. The Fugs recorded some ten albums, and Ed later released two solo albums for Warner Brothers/Reprise.

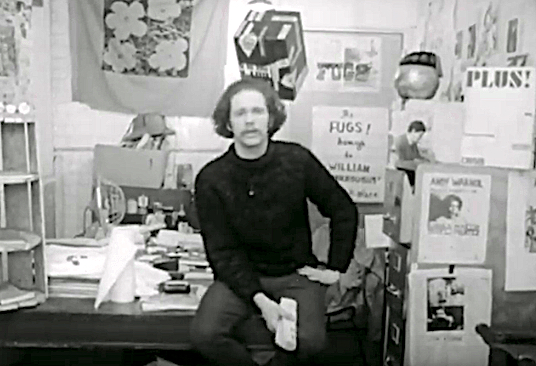

Ed Sanders at the Peace Eye Bookstore

During the same time as Fug-mania, Ed continued his other career as an established poet, known ever since his first book, Poem from Jail in 1963, as a serious writer who chronicled the rapidly changing political and social scenery of sixties America. He became an identified antiwar activist after his visible involvement with Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, David Dellinger, the Berrigan brothers, Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement, and others in the 1967 March on the Pentagon and because of his many social democratic musings in prose and poetry. Eventually, he used the Fugs’ music to spotlight and encourage political action and social change in America. The Fugs played many antiwar rallies. They often performed with Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, the Doors, and Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, and they toured Europe with Fleetwood Mac. The Fugs became to rock ‘n’ roll of the late sixties what Lenny Bruce was to comedy in the fifties. They were known for their outrageous political, social, cultural performances that made the older generation extremely nervous and uncertain about America’s future.

With all of this history behind the writer/musician/bookstore owner/songwriter, it isn’t too difficult to see where Ed was heading in carving his own unique niche in American literature and art. Ed became famous for inventing everything from new words for the changing American lexicon to new electronic instruments made from ties, gloves, etc. All of these interests boded well for the beginning of his search for an original process of writing.

In July 1975 Ed Sanders was asked to deliver a lecture on some aspect of contemporary poetics for the Visiting Spontaneous Poetics Academy at Naropa Institute’s Summer Program. Sanders then prepared what has now become his landmark lecture, published by Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights as Investigative Poetry, to articulate the belief “that poetry should again assume responsibility for the description of history” (3):

move over Herodotus

move over Thuc’

move over Arthur Schlesinger

move over logographers and chroniclers

and compulsive investigators

for the poets are

marching again

upon the hills

of history. (Investigative Poetry 5)

In his City Lights booklet Ed clearly sets forth his theory: “My statement is this: that poetry, to go forward, in my view, has to begin a voyage into the description of historical reality” (7). Here the reader will notice how closely Sanders is following in Charles Olson’s footsteps. Both poets are stating that some kind of change is imperative for their times if poetry is to move forward. Hence, projective verse; hence, investigative poetry.

Sanders argues in his new poetics that poets are responsible for “mak[ing] reality” and therefore for making freedom. He believes that dealing with reality through history and investigation can and does lead to a profound sense of freedom and a lucid understanding of reality. In his manifesto about investigative poetry he elaborates on how this form of poetry can best further an understanding of our world and ourselves. He writes, “Investigative poesy is freed from capitalism, churchism, and other totalitarianisms; free from racisms, free from allegiance to napalm-dropping military police states–a poetry adequate to discharge from its verse-grids the undefiled high energy purely-distilled verse-frags, using every bardic skill and meter and method of the last 5 or 6 generations, in order to describe every aspect (no more secret governments!) of the historical present, while aiding the future, even placing bard-babble once again into a role as shaper of the future.” (11)

Sanders argues in his new poetics that poets are responsible for “mak[ing] reality” and therefore for making freedom. He believes that dealing with reality through history and investigation can and does lead to a profound sense of freedom and a lucid understanding of reality. In his manifesto about investigative poetry he elaborates on how this form of poetry can best further an understanding of our world and ourselves. He writes, “Investigative poesy is freed from capitalism, churchism, and other totalitarianisms; free from racisms, free from allegiance to napalm-dropping military police states–a poetry adequate to discharge from its verse-grids the undefiled high energy purely-distilled verse-frags, using every bardic skill and meter and method of the last 5 or 6 generations, in order to describe every aspect (no more secret governments!) of the historical present, while aiding the future, even placing bard-babble once again into a role as shaper of the future.” (11)

While I realize this is a mouthful (it is even written in Charles Olson’s style of comma-laden explanations), I also think this paragraph best sums up for the reader the essence of the process of investigative poetry. It seems rather easy to understand and to be as enthused as the bard himself when he first learned of Olson’s liberating concept. We, too, the poets of the world, are liberated, excited, and filled with the freedom of the Sanders mantra, “move over… for the poets are marching again upon the hills of history” (5). Now, poets everywhere can raise their voices in a grace-giving chant to take control of our history, our future, and, most important, ourselves.

Through Holy Bards like Sanders and Olson, we are freed to create, to open case files, to investigate the investigators, to ask the forbidden questions of those in power, of those craving absolute power, of those striving for a modicum of power in the strained world gap of selfishness and lost love. Sanders’s contention is that poets must never again be pushed like Pushkin in the Petrograds of the painful bygone years, left to die as stifled poets writing little. Sanders describes this state as “a right-winger’s vision of paradise for a poet” (Investigative Poetry 18). We are free to assert ourselves and to shout out “NEVER AGAIN!” Poets must strive to see a new day where they can open case files, collect data, and engage in the unstoppable, fearless pursuit of the data clusters that will reveal reality and truth] However, with poets now cheered, it is only fair to warn that this new freedom-oriented pursuit of knowledge is not going to be taken well by those who hoard authority and power. Investigative poetry can be a dangerous business: consider Sanders’s The Family, his detailed investigation of the mob’s waste dumping in upstate New York (“Death by Water,” a project in progress), even his initial investigative project involving the poetry war between W. S. Merwin, Allen Ginsberg (his own hero), and the Buddhists at Naropa Institute in the late seventies, well-documented in The Party (co-authored by Sanders and his Naropa students) and in Tom Clark’s The Great Naropa Poetry Wars. Now, upon reconsidering The Party, I think that it might be more dangerous to investigate poets than dictators and evil empires a la Pushkin, but I digress. All in all, I have found Investigative Poetry inspirational for my own writing and for countless advanced students of poetry. Whatever its occasional flaws (pulling off an investigation is usually not the tidy process Sanders describes), investigative poetry is a genuine liberation for writers, teaching them that it is OK to write whatever they want to write in whatever way or style they want. Ah! Richie Haven at Woodstock, 1969: “Freedom! Freedom!!”

All of this preliminary set-up now leads to the point of this article–Ed Sanders’s use of the investigative technique in 1968: A History in Verse. Sanders has always stated that the investigative process must involve honesty, a serious confrontation of the facts, and a fearless pursuit of data, even if the consequences result in discomfort to the investigator. He clearly states in the City Lights booklet, “Therefore, NEVER HESITATE TO OPEN / UP A CASE FILE / EVEN UPON THE BLOODIEST OF BEASTS OR PLOTS” (23). Later, he adds, “And do not hesitate / to open up a case file / on anything or anybody! /When in doubt, / interrogate … ” (26). Thus Sanders states on the very first page of 1968,

I will not pretend

that I was a very big part

of ’68

I surged through the year on my own little missions …

daring to be part

of the history

of the era. (5)

I find these lines to be true to Charles Olson’s original concept, when Olson stated, as quoted by Sanders, “If a man or woman does not live / in the thought that he or she / is a history, he or she / is not capable of/himself or herself” (Investigative Poetry 26). With this said and with Olson’s admonishment in mind, Sanders begins to take his readers on a chronological journey from New Year’s Eve 1967 to New Year’s Eve 1968, moving month by month through one of the most traumatic, unbelievable, and essential years in contemporary American history.

Not since the Civil War had America been so torn and at odds with itself. These are the chaotic times that Sanders chronicles in a sensitive, poetic, serious, and, at appropriate times, light-hearted way. He realizes that on the way to the birth of a terrible beauty, many incredible events must take place that can forever change the poet himself and the people of his country. Sanders’s book is part history and part autobiography– because the poet played a bigger role in sixties America than he often gives himself credit for. He founded and led one of the most successful political/ social rock bands of recent times; he was there at the planning and events that surrounded the 1968 Democratic Convention/Police Riot in Chicago; he performed with some of the now-legendary musicians of rock music; he worked for Robert F. Kennedy’s campaign and supported Martin Luther King’s civil rights movement. So all in all, Ed Sanders has a history to tell, and unlike most historians, this writer puts all of his heart and soul into the telling of his story.

There are many times in the book when Sanders is brutally honest about himself and his contributions. For example, early on in the text he comes to realize that he cannot bring himself to chant, with the other protesters at the New York State University at Stony Brook “Pigasus for President Rally,” “Off th’ pi-ig!” in reference to police officers standing guard. He then writes that he thought it was a mistake to chant such statements, “just as I thought it was a mistake / for the Futurists / to call the Austrian gendarmes / `walking pissoirs’ “(1968 27). After the rally and concert, Sanders reflects in a very real and honest way that

It was at the Stony Brook gig

tired at dawn

I began to feel the long, craving shame

for some of my work

I didn’t have the type

of idealistic and topical repertoire

to inspire the streets

& I didn’t take the time to research & write them

Instead I was working on tunes like

“Johnny Pissoff Meets the Red Angel”

& “Ramses the II is Dead, My Love.” (27-28)

“Flower Power” Pulitzer prize-winning photograph by Bernie Boston, taken during “March on The Pentagon”, 21 October 1967.

At this point in his history, Sanders says, essentially, that the Fugs continued to perform their basic repertoire, but he felt audiences were listening in a sleepy wakefulness. He decided that he had to change and become more aware and involved in his culture and history, so after the Stony Brook shows, he went back to New York City’s Lower East Side and immediately signed a lease to reopen Peace Eye bookstore. Peace Eye was a place for intellectuals, bo-hos, politicos, and other hipsters to hang, discuss literature and revolution, and print broadsides, chapbooks, etc., dealing with everything and anything. This may actually be the point where Sanders realized the importance and perhaps necessity of research and of fearless approaches to history and reality through what later became investigative poetry, rather than just playing for time with a rock ‘n’ roll group.

Increasingly, Sanders’s story of 1968 turns to the politics of the time. Throughout the text, he chronicles such important events as Martin Luther King’s plan for the Poor People’s Campaign in Washington, DC, an event that Dr. King would not live to see. Sanders goes into a fair amount of creative research on Dr. King’s alleged assassin, James Earl Ray. He does the same thing later with Robert Kennedy’s alleged assassin, Sirhan Sirhan. Sanders also writes of My Lai. Sanders noticed two things about the massacre at My Lai. First, the incident occurred on the very same morning that Robert Kennedy announced his candidacy for president, and, second, the incident itself was a “thread of evil / that led forever to” a labyrinth (indicated in the book by a line drawing) (48). At almost every key moment of American history in 1968, like Edward R. Murrow, Sanders was there.

On page after page, Sanders informs us about the controversial events of 1968 that forever changed America. He goes into detail surrounding the Black Power salute controversy during the 1968 Mexico City Olympics and even notices Denny McLain’s thirty-one wins as a pitcher for the Detroit Tigers. Sanders is able to pull the entire year together. As he says in a later portion of the book dealing with the Chicago Democratic Convention,

That is, those crazy youth and not-so-youth

their hasty signs, their hasty props, their

hasty yells

were transformed in the

Chicago injustice

so that

A terrible beauty was born. (203)

It is this “terrible beauty” that has haunted Ed Sanders well into the nineties. Sanders is still a poet, writer, musician, and political activist of intense dedication and sincerity. Although he could have easily hibernated in the Catskills with his many accomplishments (American Book Award, NEA and Guggenheim Fellowships, record industry awards, and numerous publications and recordings), he continues to build for the future, to investigate the abyss, to challenge those in authority, to hold everyone responsible for his or her actions and decisions. He continues to produce poetry, fiction, nonfiction, his weekly newspaper, the Woodstock Journal, and his weekly Sanders Report television show. In doing so, Sanders relearns every day what his experiences of previous years had already taught him: that although there is a mighty high price to be paid for beauty and truth, the battle is worth the energy and time invested, the research and experiences endured.

Finally, the purpose of this essay is to pay homage to the uniqueness of this great American bard who has served as my mentor in my social/political and cultural art. It is my hope that this essay will at least crack open the door of understanding just enough to let the light of Sanders’s insights and good humor, his honesty and compassion and love, shine through.

Ed ends his history on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in his neighborhood bar on New Year’s Eve, 1968, where he and his wife toasted the past year:

We whistled, we shouted

we stamped on the sawdust floor

while in my soul

a year-long carillon of bells was tolling….

All your inky fury is gone, o year–

but the struggle

for freedom

& a just, sharing world

where no one is hungry or cold

is always in the air

No police state

Cointelpro or Chaos

no teargas truck no battle-maddened mind

no urge to control & enslave

can stop that struggle

or erase it

Farewell, o ’68. (245-46)

And fare thee well, O Holy Bard of honest spirit and willing quest for truth and justice. Thanks for your truthful and sincere horn of history. We are grateful for your poetic language that has shaken the establishments of bureaucratic lies to their very foundations, and in their place you have helped to birth a terrible beauty that we all can understand and cherish in the populist universe of art and culture. You have taught us the meaning of Bob Dylan’s “To live outside the law you must be honest.”

When tear gas and the smog of hate hung in the skies of 1968, where Allen Ginsberg cried to the heavens that “Chicago [and America] has no government…. It’s just anarchy maintained by pistol” (1968 203), it was there that one found Edward Sanders and the investigative poets of the past and future marching up the steep hill of history to report the terrible beauty hidden beneath the mountainous bedrock of shameful power and injustice.

WORKS CITED

Dylan, Bob. “Absolutely Sweet Marie.” Writings and Drawings. New York: Knopf, 1973. 217.

Olson, Charles. Selected Writings. Ed. Robert Creeley. New York: New Directions, 1966.

Sanders, Edward. Investigative Poetry. San Francisco: City Lights, 1975.

–. 1968: A History in Verse. Santa Rosa: Black Sparrow Press, 1997.

Interview with Ed Sanders on Yeah, Exorcism & Electric Stencil Cutting at: The Detroit Artists Workshop

Ed Sander’s Fuck You Press Archive