The World’s Poorest President Speaks Out

The World’s Poorest President Speaks Out

by Gaku Nakagawa and Yoshimi Kusaba

Enchanted Lion Books

José Mujica served as Uruguay’s president from 2010-2015. During that time, he donated 90% of his salary to charities, keeping for himself only $1,250 a month. Rather than move into the presidential residence after being elected, he stayed on his wife’s farm, raising chrysanthemums and chickens (all free-range, apparently). Rather than be driven about in a chauffer-driven limousine and a cortege of armed guards, he drove himself to and from the capitol in his ’60s-era VW Beetle. Under Mujica, “the Uruguayan economy . . . post[ed] consistent growth in GDP and per capita GDP while maintaining low unemployment rates.” It also became “the first South American country to allow abortions up to the 12th week of pregnancy,” and “the second country in Latin America to legalize same-sex marriage.” However, despite these significant achievements, “Mujica was constitutionally prohibited from seeking a second, consecutive term” (Encyclopedia Britannica).

In 2012, he was invited to speak at the Rio +20 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development. The World’s Poorest President begins at the start of Mujica’s day then: working his fields with a tractor; feeding his chickens, then his dogs, then himself; putting on clean clothes; and finally driving off in his Beetle to Rio de Janeiro to give his speech. The text of the book is an edited version of that speech.

Our civilization is based upon eternal expansion of consumption, he says; and expansion depends upon focusing on how to make more money for ourselves rather than on how to make lives better for everyone. Ultimately, we cannot agree on the terms of sustainability if we live according to the principal of attending to our personal needs at the expense of those worse off than ourselves.

My message is very simple: Economic growth and progress must add to human happiness: having satisfying relationships with others; raising children; making friends; spreading love in the world.

Note: Although this is a picture book, it is definitely one that will require an older reader for the text. The pictures are great and can be de-coded pretty easily. But the text is (I’m guessing) at the 6th or 7th grade level at least. There is a chance this is really a book for adults gussied up as one for kids: matching the simplicity of the message to the simplicity of the images.

Thrust: A Spasmodic Pictorial History of the Codpiece in Art by Michael Glover, David Zwirner Books

Thrust: A Spasmodic Pictorial History of the Codpiece in Art by Michael Glover, David Zwirner Books

The piece of attire closest to the codpiece in men’s clothing today is the athletic cup. Unlike the codpiece, however, the cup is hidden and meant to protect, whereas the codpiece was visible and meant to provoke—and more:

What was it used for, then, other than to exaggerate and adorn the mighty male organ of generation? Well, as a pocket for one thing. Or, stuffed with straw or horsehair, for shapeliness’s sake, it could help protect the more beautiful outer surface of one’s stockings against staining from smeary ointment used to treat syphilis. . . It could be used to hang things from. .

Decorative and practical—who could knock the pragmatism? The fashion trend lasted about 50 years, during the latter half of the 16th century, and was widely depicted in artworks created in the leading nations of the day—Italy and Germany, England and France (the provenances of the artists used to exemplify Glover’s theme). Glover is our docent, and Hans Holbein the Younger, Peter Bruegel the Elder, Titian, and other painters, illustrators, and etchers from the period provide the evidence for his claims. Glover’s wide-ranging historical and artistic references are tempered with a tongue-not-quite-in-cheek narrative that amuses and educates—another pragmatic value.

Propaganda

by Neo Rauch, with a story by Daniel Kehlmann (Ross Benjamin, trans.), David Zwirner Books

Propaganda was a show in Hong Kong in 2019 of new works by Neo Rauch, collected here along with “a fantasy inspired by” Rauch’s works called “Becoming Caligari” by Daniel Kehlmann. As usual, the figures in Rauch’s paintings are realistic but the settings aren’t. As Cubism tested the idea of showing objects from different angles simultaneously, Rauch’s paintings seem at time to be depicting chains of associations simultaneously, each link suggestive of its own meaning but, when taken together with the other links, working toward a meaning greater than their sum.

Rauch doesn’t like the term “surrealism,” so maybe “suggestively metaphoric” or “suggestively allegorical” is better, since the question “metaphoric or allegorical of what?” doesn’t lead to clear answers. His compositions cohere by color and by figure arrangements—staged tableaux that seem to hint at meanings that elude the viewers’ knowledge. We’ve seen these gestures and arrangements in other works (triggering our memories), although perhaps not together (and our memories fail to connect). So, the paintings retain their mystery, and viewers sense a coherence to the paintings that lies just at the tip of their tongues. American parallels might be painters Mark Tansey or (although much more commercially oriented) Mark Ryden.

Fifteen full-color reproductions appear here, several with additional pages of painting details—printed well enough for individual brushstrokes to be seen.

Arabian Satire: Poetry from 18th-Century Najd

Arabian Satire: Poetry from 18th-Century Najd

Hmedan al-Shwe‘ir (Marcel Kurpershoek, trans.)

Library of Arabic Literature / NYU Press

Hmedan al-Shwe‘ir’s wrote satires from about 1705 to 1740 in the Najd region of Northeastern Arabia in Saudi Arabia, in an area of settlements along the waidis that stretch through patches of sandy desert. His European and Asian literary contemporaries would have included Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope, Daniel Defoe, Samuel Richardson, Cao Xueqin, Voltaire, Goethe, Schiller, and Rousseau.

After Hmedan’s death, Ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab’s pact with Muhammad bin Saud in 1744 set the tone for the banishment of Hmedan’s satire, and for the banishment of secular works that ridicule authority to this very day. (Wahhabism is the branch of ultra-conservative Sunni Islam belief, to which Osama bin Lad subscribed and which continues to wrack much of the Middle East.) As with his Western counterparts, Hmedan’s satire targets hypocrisy, especially among the powerful in government and religion, bemoans his fate as a farmer and Rodney Dangerfield-like “I get no respect” from his wife and lazy children.

Here’s the beginning of an attack on a member of the idle rich whose toughness is all hat and no hair (from the seventeenth poem):

Mani‘ sits on his rooftop and plays horseman, / a hero doing battle from the safety of his parapet. / At the sound of alarm outside, / he and his belle sit up and take a peek: / Coffee cup in his right hand, / hubble bubble [hookah] in his left. / Should he venture into the street, / a cat could despoil him of his cavalry coat.

Hmedan’s writings are infused with adages, maxims, and proverbs, which remain frequently quoted in the Arab world, according to Marcel Kurpershoek, the translator.

Currently, the Library of Arabic Literature series has over 40 hardcovers, most of which seem to be available in paperback, too. Readers of a more scholarly bent should know that the hardcover editions include original language/translation facing pages and extensive notes and explanations regarding the critical apparatus used for each volume. Arabic-only versions of these books are available as free PDFs from the publisher.

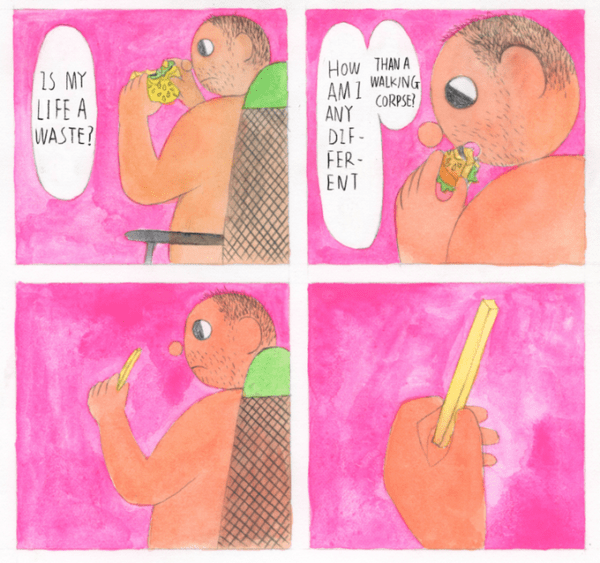

Naked Body: An Anthology of Chinese Comics

Naked Body: An Anthology of Chinese Comics

Yan Cong, R. Orion Martin, Jason Li (Eds.), Paradise Systems

In 2014, the editor of the comic book Narrative Addiction published contributions that met the following criteria: 5-page stories featuring nude characters. By Western standards, that’s a pretty tepid attempt at edginess. But the situation for the editor of Narrative Addiction—a comic book series based in mainland China—is summarized in one panel from Zhai Yanjun’s story “Xiao Ma’s New Outfit,” about of new, popular line of “clothes”: “You’ll run into trouble if you keep this up. There were more than 30 people here! Be careful who you influence.” There is nothing metaphorical about those lines. The Chinese government does not have organizations like the ACLU or even Amnesty International to bother it about the CCP’s censorship policies. And cartoons involving nude characters that bitch about the system involve some measure of risk-taking, even with audiences of 30 or less.

The range of stories and illustration styles here is refreshingly broad— from whimsical to realistic in its figurative depictions and tales. Contributors come from Shenzhen, Beijing, Shanghai, and other cites. Most contributions are non-political but others can be read as veiled attacks on various aspects of internal Chinese political policies. Some stories have sex, some don’t. All are interested in visual story telling and exploring what can be done with the medium. In those regards, then, Naked Body can be seen as a Chinese version of Fantagraphics’ Now series.

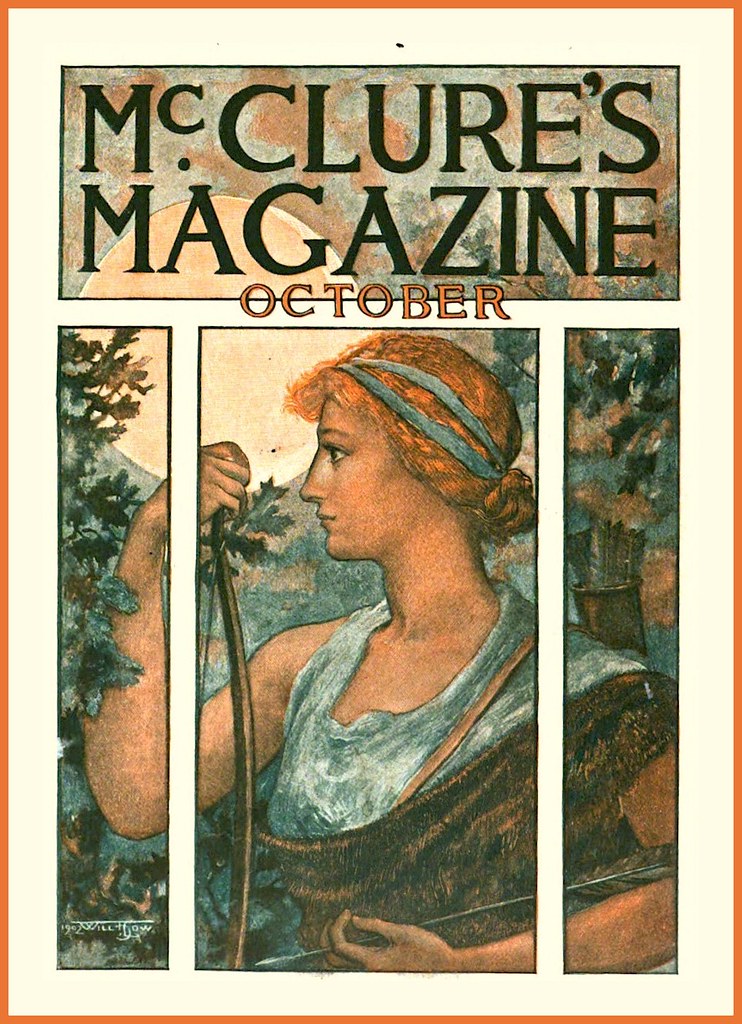

McClure’s Magazine, October 1902, where Lincoln Steffens’s “Tweed Days in St. Louis,” appeared, and is considered the first work of muckraking journalism.

The Shame of the Cities

by Lincoln Steffens, Belt Publishing

With the death of newspapers nationwide—especially in small towns—due to the influence of Internet Diversions, Inc., has come a lower level of responsibility and accountability among those on city and county payrolls, since fewer third-parties with the financial resources are available to independently verify how the cities and counties are actually run and what tax monies actually pay for. That third party was often the local newspaper, which tracked financial and other legal records, interviewed witnesses, and otherwise connected the dots. Small town papers, where they exist, rarely stray from self-congratulatory boosterism.

Over a century ago, muck-raking journalists began exposing corruption in local governments in excruciating detail and with plenty of evidence that helped usher in reforms across the country. (Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle is the most famous example of this, although in the form of a novel.)

Published in 1903, The Shame of the Cities collects seven exposés of six cities: St. Louis (twice!), Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Chicago, and New York. Trump-like fiefdoms of city government corruption that were eventually brought to heal (at least for a while) by judges and legislators who couldn’t be bought, and by citizens of these cities, which lacked—unlike today—a 40% base of voters who were happy with the corruption. “Minneapolis was an example of police corruption [!!]; St. Louis of financial corruption. Pittsburgh is an example of both police and financial corruption.” In essays of 20-30 pages, Steffens names names, reprints receipts and other incriminating evidence, describing how criminal activities were organized.

If you haven’t yet had enough of malicious greed over the past four years, you may be interested in reading about the historical precedents described here.

Chirri & Chirra Under the Sea

Chirri & Chirra Under the Sea

by Kya Doi [David Boyd, translator]

Enchanted Lion books

Chirri and Chirra’s latest adventures under the sea begin as a bike ride through a cave the girls discover on one of their perpetual excursions. Always fun, imaginatively plotted, whimsical and cute, Chirri and Chirra’s stories are devoid of character development and moralizing; instead, they enter worlds of wonder, welcome, and imagination. In Under the Sea, they visit a salon and sit on seashell sofas; encounter squids, eels, coral, and an octopus. Chirri eats a sea-spray parfait à la conch, and Chirra has a marine soda jelly topped with pearl cream, after which they go to a musical. It’s all very charming and cute and doesn’t add up to anything beyond fun. But sometimes that’s just enough.

ceremonies in bachelor space

ceremonies in bachelor space

by Russell Edson

Tough Poets Press [poetry]

A reprint of Edson’s 1951 debut shows Edson’s as a Gertrude Stein wanna be (“The rosen hill, Rose, we upward the rosen hill . . . / Rose after, Rose fore. Rose is my secret door”), including verbs as nouns nouns as verbs and other make-it-new-isms, that create images so new you’d swear they were blather. Note to self: Avoid all poetry requiring secret decoder rings.

All books reviewed by Tom Bowden can be purchased directly from Book Beat: call (248) 968-1190 or order through our Bookshop.org page.