In recent years my tastes have gravitated largely toward nonfiction. Not that I don’t enjoy occasional forays into creative writing—usually short stories, and during lengthy business travel I’ve binge-read crime novels. But the last really extensive work of fiction I skimmed through was, I think, The Warren Report.

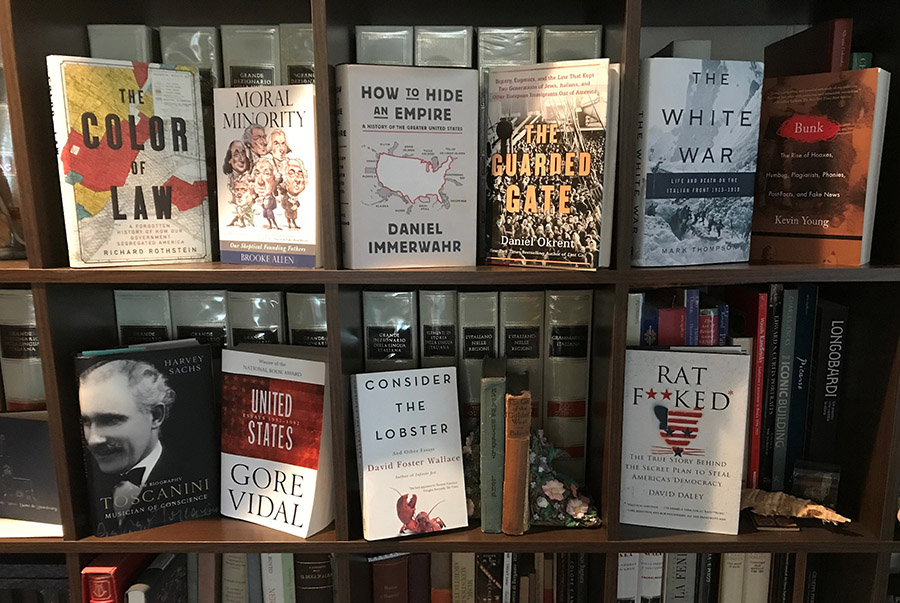

I also tend to read several books at once, at differing speeds, a quirk developed unintentionally over four decades in the publishing business. I give credit to the NYRB and to NPR author interviews for several of the “finds” among the titles below that might otherwise have escaped my radar. The “ten top” (no particular order) I’m enjoying at the moment are:

1. Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States (New York, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2019, ISBN 978-0-37417-214-5)

Mark Twain and Gore Vidal both observed, in their time, that few things upset US politicians more than to refer to America as an “empire,” but it most undeniably has been since the late 19th century. And in few cases was this empire acquired and expanded other than by appalling destruction and bloodshed, at times to the point of (nearly) attempted genocide. Well written, informative, but always unsettling, this study is, in the words of one reviewer, “a breakthrough [in] our collective understanding of America’s role in the world.”

2. Daniel Okrent, The Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics, and the Law That Kept Two Generations of Jews, Italians, and Other European Immigrants Out of America (New York, Scribner, 2019, ISBN 978-1-4767-9803-5)

The “immigration battles” have fluctuated over the course of America’s history and the issue is more timely than ever, but I’ve rarely read a clearer, more thoroughly researched book addressed to a non-specialist readership. The shifting targets of “which” ethnic groups or nationalities were or weren’t “undesirables” at any given time (Ben Franklin wanted to keep out Germans), and the profoundly cynical (yet exploitative) motivations behind so much US legislation over the decades, resonates very loudly in our current time.

3. Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York, WW Norton, 2017, ISBN 978-1-63149-285-3)

Here, on the other hand, is an aspect of history I knew little about. Even the author reveals that until he began this research he too, like most people, was unaware of much of this history of subtly (and not so subtly) legislated segregation: as one reviewer described it, “racism hiding in plain sight.” Meticulously researched, very well written.

4. Mark Thompson, The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919 (New York, Basic, 2008, ISBN 978-0-465-01329-6)

This sat in my “waiting list” (a genteel term for piles of books stored under our billiard table) at the tail end of titles I purchased during a “World War I” binge, on occasion of the recent centennial of that world-changing conflict. Like most people more familiar with English language histories, I was fairly well versed about warfare on the French-German front but only vaguely acquainted with the Italian-Austrian campaign, and that via the semi fiction of Hemingway’s Farewell to Arms. The history of that front is one of incredible hardships in high-altitude mountain warfare, some of the most vicious combat and highest casualty percentages of the war, remarkable feats of military engineering and incredible heroism by front-line troops thrown into impossible situations by the incompetence of their generals. The author provides illuminating political and cultural background to the lead-up to Italy’s involvement, and the aftermath of what may be described as its “disastrous victory” and a postwar crisis which set the groundwork for the birth of Fascism.

5. Kevin Young, Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News (Minneapolis, Graywolf Press, 2017, ISBN 978-1-55597-816-7)

The title says it all. To be consumed in sections and swatches, but every chapter a delight.

6. David Daley, Rat F**ked: The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy (New York, Liveright, 2016, ISBN 978-1-63149-162-7)

Wow, talk about a book that should be required reading in every high school civics class (do they still have those?). Of course, maybe after they tweak the title for school-ager consumption. Years ago I enjoyed Mark Monnier’s Bushmanders & Bullwinkles: How Politicians Manipulate Electronic Maps and Census Data to Win Elections (Chicago, U of C Press, 2001, ISB 0-226-53424-3) but considered it a relatively localized phenomenon. Now however, Rat F**ked reveals a terrifying reality behind a large-scale systematic approach by an entire political party to subvert everything the American experiment was “supposed” to guarantee. George Carlin famously quipped that “Even in a fake democracy, people ought to get what they want once in a while.” This study clarifies that one political party has been working to ensure that may never happen. Then again, maybe this book should not become required reading for young people: many who I know have become so cynical about a “rigged system” that this sort of information might drive them to give up voting altogether. Eye-opening and profoundly thought provoking.

7. Brooke Allen, Moral Minority: Our Skeptical Founding Fathers (Chicago, Ivan R. Dee, 2006, ISBN 978-0-226-40118-8)

From the conception of the United States through the mid Twentieth Century it was an uncontested “given” among serious historians that the great American experiment was founded on the humanist ideals of the Enlightenment. Yet from the mid-20th-century rise of McCarthyism, intensified through the Regan era, and rendered a red-hot agenda goal in the 21st century, dogmatic religious extremists have relentlessly pursued the revisionist fantasy that the founding fathers had “Christian principles” in mind. The obvious fallacy of the argument might make for an amusing side-story were not its underpinnings so sinister: the increasing push in recent decades to protect bigotry, discrimination, and exclusion behind the pious shield of “religious freedom.” As the author points out, the guiding spirit of the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution was not Jesus but John Locke. This small book is an important corrective in these disturbing times.

8. Harvey Sachs, Toscanini, Musician of Conscience (New York, WW Norton, 2017, ISBN 978-1-63149-271-6)

As flap copy recites, “Arturo Toscanini—recognized widely as the most celebrated conductor of the twentieth century—was once one of the most famous people in the world. Like Einstein in science or Picasso in art, Toscanini transcended his own field, becoming a figure of such renown that it was often impossible not to see some mention of the maestro in the daily headlines.” Sachs is the foremost expert on Toscanini and this new, monumental biography underscores the enormous influence of this towering personality well beyond the boundaries of classical music, as a man of uncompromising moral stature, a staunch antifascist and champion of the oppressed, who for instance travelled at his own expense to establish an orchestra of refugee Jewish musicians in Palestine in the late 1930s. The current “stay home” directive gives me the opportunity to pick up where I left off last year (page 300 out of 860+) with this fascinating bio of a remarkable artist and man.

COLLECTED ESSAYS:

9. David Foster Wallace, Consider the Lobster and Other Essays (New York, Little, Brown & Co, 2005, ISBN 0-316-15611-6)

I first learned about the work of David Foster Wallace in a roundabout way. Some two decades ago an Italian friend asked if I knew his work — saying “He’s an absolutely brilliant writer”—and this guy had read him in translation, not English. I enormously admire high craftsmanship and I’ve since read everything by DFW I could find… Yes, including all the way through Infinite Jest and Broom of the System. He was the most stunningly gifted American writer of the last generation (as Zadie Smith wrote, “He can do anything with a piece of prose”) and I’m enjoying this essay collection again. How not to love someone who can offer this scathing observation (in “Authority and American Usage,” about the introduction to The American College Dictionary) “This is so stupid it practically drools.” Delicious.

10. Gore Vidal, United States: Essays 1952-1992 (New York, Broadway Books [Random House], 1993, ISBN 0-7679-0806-6)

For breathtaking skill with the English language and insuperable wit as an essayist, the master in the second half of the 20th century was Gore Vidal. And regardless one’s view of his politics he was, undeniably (as one reviewer wrote), “The century’s finest essayist.” All the essays in this collection are insightful, many brilliant, and each positively dripping with masterful style. One of the pieces (a response in the New York Review of Books letters following a petty review of Vidal’s Lincoln) contains a line that has become an oft-recycled classic: “This is the sort of thing that gives mindless pedantry a bad name.” Priceless enjoyment.

Gabriel Dotto, is Director of the Michigan State University Press. He has recorded a video on How to Get Your Book Published.

A selection of Gabriel Dotto’s book list appear in our online Bookshop.org catalog.

Amor librorum nos unit