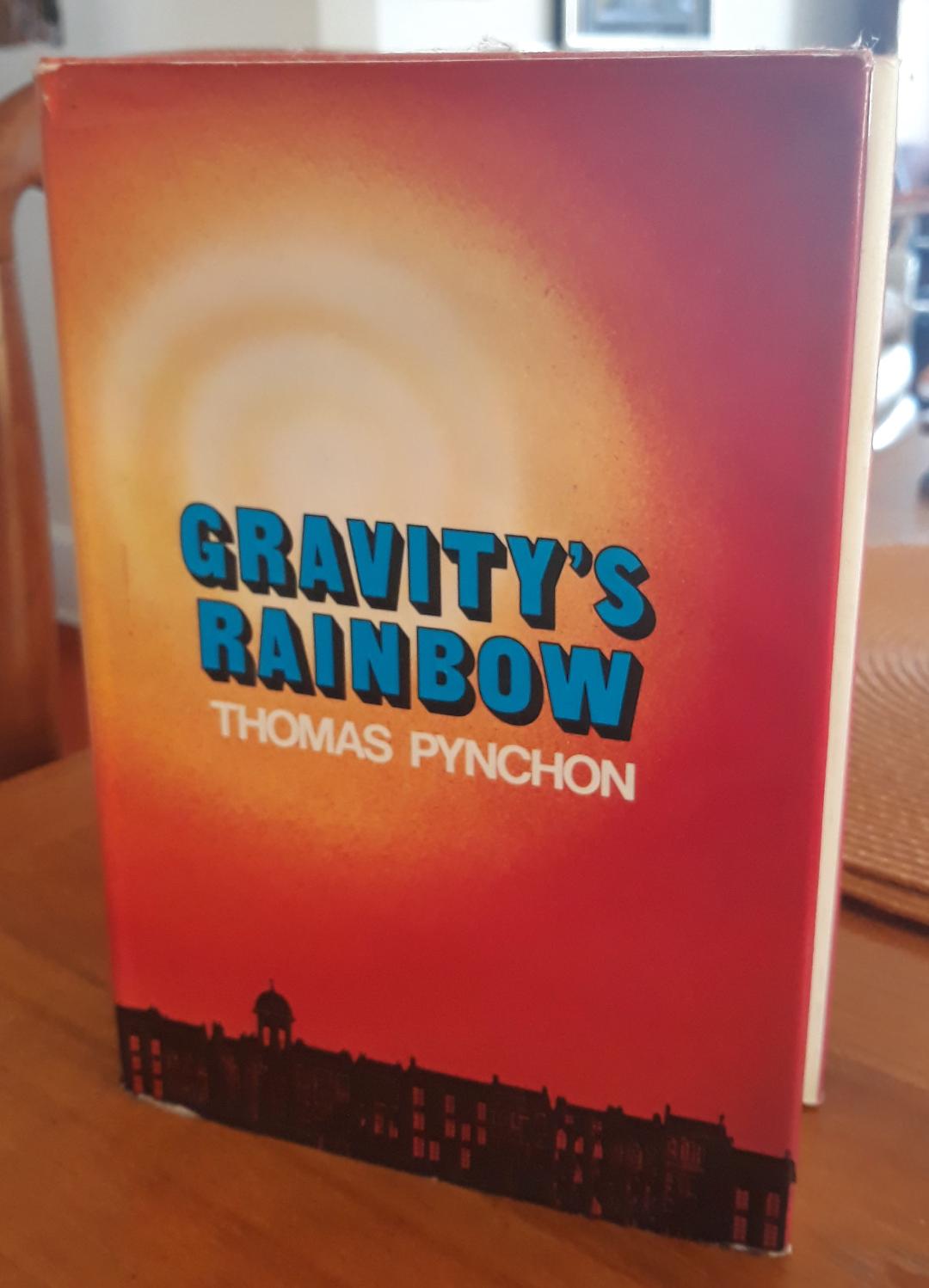

Because of my writing and research, I don’t get to read much fiction. This even though I have long had the suspicion that I might be smarter if I did. Fiction seems to get at truths that are more deeply felt than the social science I need to read in order to keep up. One exception is Thomas Pynchon. I pretty much read everything he puts out, ridiculously long or thankfully short. I bought the Penguin edition of 1984, published in 2003 to mark George Orwell’s centennial simply because Pynchon wrote the introduction. (I have to say, though, that in that case I prefer Orwell’s nonfiction, particularly his essays and the classics The Road to Wigan Pier and Homage to Catalonia, to his novels.) Pynchon’s masterwork, of course, is his third novel Gravity’s Rainbow, which I have read a number of times since first encountering it in the mid-1970s. Gravity’s Rainbow is for me one of the essential American novels, on the order of The Scarlet Letter, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Moby-Dick, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Great Gatsby, On the Road, and Beloved. (To that list I would now add The Overstory by Richard Powers.) Novels that for me come at crucial times in American history, books that seem to capture the spirit of the nation at a turning point, for better or worse. If On the Road (which Pynchon cites as a Great American Novel) can be said to mark the birth of postwar counterculture, then Gravity’s Rainbow may be read as heralding its demise. Gravity’s Rainbow registers the rise of the military-industrial complex, which emerged from the ashes of the Second World War, and it presages the ultimate defeat of the Romantic imaginary that underpinned the so-called counterculture. (That defeat is more directly addressed in Vineland, which is not coincidently set in 1984, the year Ronald Reagan was reelected, as well as Inherent Vice, the psychedelic-noir whose main character, the drug-addled Doc Sporto, stumbles through the beach communities of LA oblivious to the fact that the sun is setting on the hippie Elysium.) Gravity’s Rainbow is not an uplifting book, but as the critic Richard Poirier wrote, it “caught the inward movements of our time.” It’s a book I can’t imagine not ever having read or living on without.

Because of my writing and research, I don’t get to read much fiction. This even though I have long had the suspicion that I might be smarter if I did. Fiction seems to get at truths that are more deeply felt than the social science I need to read in order to keep up. One exception is Thomas Pynchon. I pretty much read everything he puts out, ridiculously long or thankfully short. I bought the Penguin edition of 1984, published in 2003 to mark George Orwell’s centennial simply because Pynchon wrote the introduction. (I have to say, though, that in that case I prefer Orwell’s nonfiction, particularly his essays and the classics The Road to Wigan Pier and Homage to Catalonia, to his novels.) Pynchon’s masterwork, of course, is his third novel Gravity’s Rainbow, which I have read a number of times since first encountering it in the mid-1970s. Gravity’s Rainbow is for me one of the essential American novels, on the order of The Scarlet Letter, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Moby-Dick, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Great Gatsby, On the Road, and Beloved. (To that list I would now add The Overstory by Richard Powers.) Novels that for me come at crucial times in American history, books that seem to capture the spirit of the nation at a turning point, for better or worse. If On the Road (which Pynchon cites as a Great American Novel) can be said to mark the birth of postwar counterculture, then Gravity’s Rainbow may be read as heralding its demise. Gravity’s Rainbow registers the rise of the military-industrial complex, which emerged from the ashes of the Second World War, and it presages the ultimate defeat of the Romantic imaginary that underpinned the so-called counterculture. (That defeat is more directly addressed in Vineland, which is not coincidently set in 1984, the year Ronald Reagan was reelected, as well as Inherent Vice, the psychedelic-noir whose main character, the drug-addled Doc Sporto, stumbles through the beach communities of LA oblivious to the fact that the sun is setting on the hippie Elysium.) Gravity’s Rainbow is not an uplifting book, but as the critic Richard Poirier wrote, it “caught the inward movements of our time.” It’s a book I can’t imagine not ever having read or living on without.

Editor’s note: For a more sustained and trippier analysis of GV, travel to Carducci’s blog; the Motown Review.

I have a fairly respectable record collection — close to 3000 titles combining vinyl and CDs, covering a broad spectrum of genres. But if I had to pick one record that I couldn’t live without, it would have to be Thelonious Monk’s Straight, No Chaser, first released in 1967 on Columbia. It’s one of the first jazz records I ever heard, having checked it out from the Roseville Public Library when I was in junior high and studying with Motown baritone sax player Lanny Austin at Detroit Wayne Music Studio, located at the time on Gratiot near Seven Mile. The vinyl pressing I currently play has been in my collection for nearly five decades, since I was a freshman in college. It still sounds great even if it’s showing a few signs of wear. (There is a certain element of the sound that’s attributable to the upgrades in my playback system over the years. While I’m still using the same Pioneer turntable from the 1970s, I’m pushing the sound through a McIntosh tube preamp/solid state amp hook-up to power Mirage bipolar speaker towers at 150 watts a channel at 6 ohms. But that just makes it all the easier to appreciate the performances, which continue to satisfy.) While signing with Columbia offered Monk a broader audience and a mainstream imprimatur, that catalog, especial the later recordings of which Straight, No Chaser is among the last, was for decades underappreciated. Part of it may have been that for more than a decade Monk worked with the same sax player, Charlie Rouse, whose fame never reached that of Monk’s earlier collaborators — Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, all of whom went on to legendary solo careers. There is also the fact that much of the catalog reworks compositions Monk recorded during his heyday as the High Priest of Bop, generally using the same four-piece combination of piano, sax, bass, and drums. Then there’s the fact that Rouse tended to play sharp, which may have annoyed some of the more “refined” listeners. But to my ear, every one of the tracks on Straight, No Chaser is about as perfect as they can be. In addition to the title track, there’s the homage to Duke Ellington, “I Didn’t Know About You,” and the stunning stride-inflected solo rendition of Harold Arlen’s “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea.” In the years since that first listening, I’ve acquired most of the Columbia catalog either on vinyl or CD, as well as recordings from earliest days on Blue Note, Prestige, and Riverside to the last ones made in the early 1970s and released Black Lion before Monk stop performing publicly. But Straight, No Chaser is still the one I go back to the most.

Vince Carducci has written for many publications over the last two-and-a-half decades, ranging from alternative weeklies and webzines to academic journals, anthologies, and encyclopedias. He is Dean of Undergraduate Studies at College for Creative Studies, which according to design guru Steven Heller is “one of the vanguard art, craft and design schools in the nation, in the surprisingly beautiful city of Detroit.” His art reviews are collected online at Motor City Art Review: A blog about art, culture, and other stuff Follow him on Twitter @cultrindustreez.