I arrogantly recommend… April 2020 edition, is an irregular column of book reviews by our friend Tom Bowden, a book devouring monster who tells us, “The title comes from the British comic Stewart Lee in his occasional emails, about the books, movies, and music he listens to. (He’s a huge Cage and Derek Bailey fan.).”

The Unseen

The Unseen

by Roy Jacobsen (Don Barlett and Don Shaw, translators) (Biblioasis)

Water and weather often make for unnamed, dangerous characters in Norwegian fiction. Add to that the 55,000+ islands that gird the peninsula—many of which are (or were) lived on by single families that live just above subsistence living, raising milk cows and sheep on the land and fishing the fjords. All at the mercy of the winds and water, which are unforgiving, merciless, and straight from the Article Circle.

The Unseen follows two generations in the life of the Barrøy family on their island, a plot of rocks and fields a half-mile long by a quarter mile wide. No specific dates are given in the book, but it seems to cover years prior to and after World Wars I and II. The slow changes that happen to the Barrøys and the neighboring community—changes related to tradition and creature comforts—sometimes occur in a single act, such as allowing women to sit at the dinner table, instead of just the men (until then, there were just enough chairs for the men).

One thing that doesn’t change is the terseness of verbal exchanges, which usually consist of only the bare minimum and returning unwanted questions with silence. Taciturnity reaches absurd levels about three-quarters through the book when, after returning from two weeks at school, one character arrives home to find to new children living there, one a toddler, the other about seven. When he asks who they are, he is only told their names, and that’s that.

Traditions may have helped shape certain behaviors, including assigned gender roles, but survival is no respecter of cultural norms, and over time roles become distributed more along levels of strength and cunning: hauling in fishing nets; rowing among the islands and mainland; scything fields; milking cows; cutting, salting, drying and selling fish; mending and making new nets. The work is year-round and unrelenting, often from pre-dawn to midnight, in all weather, including gales, sleet, and snow. Once a child is old enough to walk, the child is old enough to work. And there is never a guaranteed pay-off for the work. That’s up to the wind and weather.

Forgotten Journey

Forgotten Journey

by Silvina Ocampo (Suzanne Jill Levine and Katie Lateef-Jan, translators) (New Directions)

It’s hard to know which of this book’s many qualities to begin with. Ocampo, an Argentine writer—an important Argentine writer in her day—created in her first book, this collection of stories, something akin to Joyce’s Dubliners: separate short stories, yes; but a cohesive tone, attitude, and view that allows it to be read as a novel about what it means to be, well, not a Dubliner, but, circa 1935-1937, what it means to be Argentine, or even more specifically, from Buenos Aires. A mix of European sensibilities and cowboy ranching rough-and-tumble, decaying wealth and eternal poverty.

And in the language, one can imagine Ocampo having influenced [Clarice] Lispector and [Robert] Bolaño— for the distinctive, highly personal style (although not as hermetic as Lispector), and Bolaño for the way to express one’s view of the world via rhetorical motifs and moral themes. Let’s listen in:”She could hear the sound of spoons clinking through the slightly opened door, which signaled the arrival of a tapioca rice soup that tasted like childhood on a tray decorated with stars.” Pretty much every sentence of the book is like that. Suzanne Jill Levine and Katie Lateef-Jan did a fab job translating the novel.

The stories read as prose poems, more interested in capturing the ephemera of moments, then the emotional impressions they arouse, or in plotting out a conventional story.

Ocampo and her sister came from a wealthy family, and together they published the Argentine literary journal Sur. (Bolaño often had similar literary sisters in his novels.) Ocampo was a major talent who attracted major talents: Borges was lifetime friend of hers and her husband’s, the novelist Adolfo Bioys-Casares (author of The Invention of Morel, among others), and the three of them sometimes collaborated together (but not in this collection).

Published when Ocampo was 34, it may have been her first book but, compared to the works from 20-somethings, its more mature in its range of experiences to draw upon, yet is utterly unself-conscious in the way it expresses itself.

“What matters is what we write: that is what we are, not some puppet made up by those who talk and enclose us in a prison so different from our dreams.”

–Silvina Ocampo, Thus Were Their Faces

The Promise

The Promise

by Silvina Ocampo (Suzanne Jill Levine and Jessica Powell, translators) (New Directions)

A woman briefly passes out, falls off an ocean cruiser, and awakes in the water, the ship leaving her far behind as she passively floats on the water, writing in her head a book dedicated to Saint Rita about her life (the woman’s) in exchange for salvation.

The memories focus on different people in her life, what she saw and heard them do and say, friends, lovers, family. As the book goes on, the accounts become of things she could not have experienced with her friends—expressed in terms of an omniscient narrator commenting on the actions and occasionally talking to the friends (who hear and respond, even though she’s not “there”)—the unreality increasing as her consciousness dissolves to (presumably) death. Emotions, tactile sensations, and passions compliment and conflict with each other, as does the ambiguity of her desire to live or die.

The Little Grey Men

The Little Grey Men

by B.B. (NYR Kids)

A charming adventure for 8-12 year-olds about three gnomes who go on an adventure in search of their lost brother. The brother had struck out on his own adventure two years previous and hadn’t returned, searching for the source of the river that flows past their home.

The focus of the book is really about nature; plants, birds, fishes, and all manner of four-legged critters, their habits and habitats. As is fit for a book written for young readers, there are scares and bouts of heroism as the gnomes prove to themselves their capabilities and build friendships along their journey.

Nothing cutesy or sappy here—there are deaths and significant hardships (as there were in Britain the time this book was first published in 1942). Urban and suburban readers beware: you may discover your own alienation from nature rises in direct proportion to the number of words you have to look up.

The Suspended Passion: Interviews

by Marguerite Duras (Chris Turner, translator) (Seagull Books)

Novelist, filmmaker, and scriptwriter whose obsessive theme was tragic passion (is there any other kind?), Marguerite Duras was extensively interviewed in 1987 by the Italian journalist Leopoldina Pallotta della Torre, whose questions track the arch of Duras’s life, from childhood in Vietnam; her tortuous relationship with her mother; her friends, lovers; writing and filmmaking; and near-fatal alcoholism.

“It’s only out of what is missing, out of the blank spaces that appear in a sequence of significations — out of the gaps — that something can be born.” — Marguerite Duras

The Treasure of the Spanish Civil War

The Treasure of the Spanish Civil War

by Serge Pey (Donald Nicholson-Smith, translator) (Archipelago Books)

I walked all around the orchard. Under the peach tree, the sign read simply Josep Sabaté Llopart. The apple tree bore the name of Antonio Franquesa Fumoll. The pear tree was Simon Gracia Fleringan, and the plum Josep López Penedo. At the foot of the lemon tree was a bicycle wheel, and on each spoke a letter on a piece of cardboard: painstaking small capitals spelt out the name f.r.a.n.c.i.s.c.o. s.a.b.a.t.é. Engraved on a birdhouse hanging fro the orange tree, in florid lettering, were the words Fancisco Denís Diez. In the apricot tree was a smiling photograph of Matín Ruiz Montoya, with a special mention of “Barcelona.” Directly into the bark of the olive tree my uncle had carved Ramón Vila Capdevila (Caraquemada), and, in big capitals, VIVA. On the banana tree bark had grown over the first letter of a first name: ablo. My uncle had planted a tree for each of his network comrades who had been assassinated between 1949 and 1960.

The Treasure of the Spanish Civil War’s intertwined stories, often told as a child’s memory, deal with the lives of Spaniards imperiled, first, as enemies of Franco’s fascist regime during the nation’s civil war and, second, as refugees in French internment camps.

The lives of refugees, of immigrants from war-torn countries, often primarily evoke various shades and levels of Hell. But the implicit message of The Treasure is the hope found when struggles for work, impedance, and safety are done in the name and interest of everyone. Children and housewives, as well as armed resistance fighters, pool together to elude the evils of fascism. Best stories: the title story and “The Bench,” which is a model of suspense writing.

Machines in the Head: Selected Stories

Machines in the Head: Selected Stories

by Anna Kavan (NYRB)

At her best, Kavan consistently presents a rational-seeming worldview steeped in paranoia: Nobody means what they say—and their reasons for duplicity sound quite natural—no allies exist, and crushing failure hems in the protagonists on all sides.

The emotional extremes described in her earlier stories—emotions changing almost by the paragraph—are described with such nuance, in how and by what they are provoked, that they seem plausible; so that, by agreeing with the reasonableness of the narrative voice, one consents to the narrow view and relentless fear of pursuit and harm, and feels a sense of discomfort and paranoia throughout.

I had a friend, a lover. Or did I dream it? So many dreams crowding upon me now that I can scarcely tell true from false: dreams like light imprisoned in bright mineral caves; hot, heavy dreams; ice-age dreams; dreams like machines in the head. –Anna Kavan

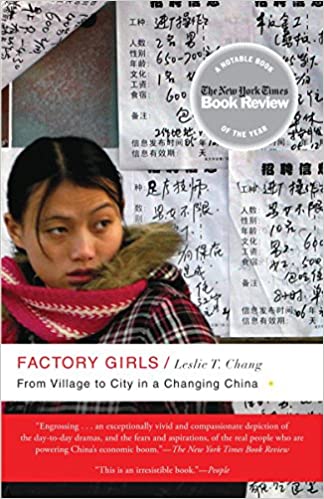

Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China

by Leslie T. Chang (Spiegel & Grau)

Twelve years ago or so when I first travelled to China to teach, one of the full-time faculty members, a German professor of mathematics, wanted to immediately disabuse me of any notion that China is somehow a “communist” country: “China is John D. Rockefeller’s wet dream. Everybody works 12 to 16 hours a day, six days a week. There are no labor unions. What’s not to like?” Leslie T Chang illustrates some of what’s not to like in her book of reportage, Factory Girls, which primarily follows two young women, migrants from the countryside seeking to meet their fortune.

Chang, herself Chinese-American, assigned to the Wall St. Journal for over a decade, with an ability to speak Mandarin, interviews, exchanges text messages and emails with, and meets with their friends and employers to discover first-hand what life might offer a 17-year-old girl with no prospects in her home community. And what offers many of these migrant workers is a grueling work schedule, confinement to a corporation “campus” and living dormitory-style four- or six-to-a-room six days a weeks, and the ability to call home once a month or sometimes even once a week.

The men the women meet are largely con artists as poor off as the women, but the men don’t face constant reminders from a patriarchal society that has little use or respect for them. (For more on that, see from last year Leta Hong Fincher’s Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China. And yet, the women’s worst enemy often is themselves, delusional (to the point of willfulness) about their prospects—hope again triumphing over experience—, as ready to be taken in by a make-money-fast scheme as quickly as they are willing to take in others.

Underemployment is a fact of life for many people who do have jobs, and the jobs there are tend to pay poorly, even for those with college diplomas. (“Twelve hours a day is underemployment?” Depends on the work (not in factories), which is s-l-o-w-l-y spread across the span of the day. Boasts about one’s skill levels are common and commonly have little to do with actual ability. Both employers and employees in these lower-tier jobs are constantly on the make, and a few big bucks made in one month may all be gone the next.

Despite the odds, a curious type of optimism drives these women; the alternative is to face what the reader has encountered on every page of this 400-page book: grim resignation to continued poverty.

To read more of Bowden’s book reviews, subscribe to our newsletter or search our website for: i arrogantly recommend. Reviewed Books can be purchased direct from Book Beat, by calling 248.968.1190 or email: BookBeatOrders@gmail.com or visit our online Bookshop and browse; I arrogantly recommend…