The theater, which is in no thing, but makes use of everything–gestures, sounds, words, screams, light, darkness–rediscovers itself at precisely the point where the mind requires a language to express its manifestations…. To break through language in order to touch life is to create or recreate the theatre. –Antonin Artaud

Shadow-theater is an ancient art –like ceramics, doll making, poetry and drawing, it reaches into the dawn of mankind’s instinct for telling stories and communicating with others. Any young child who has experienced how hands and objects can cast shadows against a wall has touched an ancient part of their being. The performance of shadow plays can be traced to ancient Egypt, India, Indonesia and China and was most likely attached to ritual, the high priest class and sacred allegory. Ancient Egyptian dancers once cast their shadows across polished stone and this might be one of the earliest know examples of shadow theater.

It is in Bali that the shadow play has the strongest mystical element. There the dalang begins not only with an offering and a prayer but with a special ceremony to ”wake up the puppets” sleeping in their box. After the performance, he speaks a mantra to revive puppets killed during the show. The tempo of a shadow play differs from Java to Bali. ”The Javanese like everything to be kind of slow,” Mr. Sumarsam says. Partly because they take it slow, Javanese shadow plays last all night – from about 9 P.M. till dawn. Viewers may nod off, dream and awaken, living in the world of the shadows.–Eileen Blumenthal, The Coarse and the Sacred Are Fused in Shadow Plays

After Antonin Artaud witnessed a Balinese shadow play with dancers and a full gamelan production at the Paris Colonial Exposition in 1931, (the same Expo where they displayed “Human Zoos”) –it became a key event, triggering ideas for his theories and book, The Theater and It’s Double. The displays at the Paris Expo reintroduced primitive rituals into Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty, taking modern theater into a new direction, back to its ancient origins.

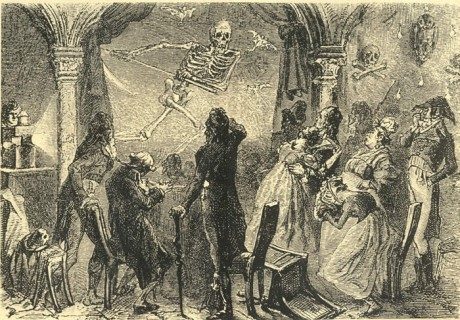

[illustration of Robertson’s phantasmagoria, Paris, 1797.]

[illustration of Robertson’s phantasmagoria, Paris, 1797.]

“I am only satisfied if my spectators, shivering and shuddering, raise their hands or cover their eyes out of fear of ghosts and devils dashing towards them; if even the most indiscreet among them run into the arms of a skeleton.” E.T. Robertson, Robertson’s Phantasmagorie in Adventures in Cybersound

The Magic Lantern arrived in the early 1600s and used a lens, mirrors and light source (usually oil or candles) to project images. The magic lantern was also known as the “lantern of fright” –for its ability to project apparitions and images of the dead. The ingenious scholar-priest genius/crackpot Athanasius Kircher is credited with the invention, an important forerunner and link to motion pictures, the camera and photography. The first images made for projection were of devils, demons and saints,used in churches to frighten viewers and teach Christian stories and allegories. The Belgian stage magician Étienne-Gaspard Robert (1763–1837) who went by the name Robertson, improved on projecting techniques and moveable lenses he acquired through studying Kirchner’s writings. In 1798 he created his first phantasmagoria, forerunner of the modern day Halloween spook-house. These horror spectacles, featured ghosts and raising the dead, grew in popularity and inventiveness, and eventually shut down by the authorities.

The earliest fantasy films made by cinema pioneer George Milies (who was a stage magician before he turned to making films) included many fantastic devils, demons and apparitions –but rather than religious allegory, Milies’ fantasies were an homage to the vogue for late 19th century stage magic and magicians. His films were not only the first special effects films in cinema, they cleverly spoke to the invention itself, portraying magicians in service to science and scientists in service to magic. They are both humorous satires and self-reflective artworks on a transitional period between staged theater and cinema.

The desire to capture and fix images has a long history that includes the popular use of hand cut silhouettes, the camera obscura, small optical toys, kaleidoscopes, dioramas, panoramas –and the more intense, elaborate magic lantern phantasmagorias. A peak interest in these optical devices, fed by the public, led to the invention of photography in the mid 19th century, when images could finally be permanently fixed. The invention was not a single flash discovery but a series of many small diverse developments in chemistry and physics by inventors over time. Photo historian Geoffrey Batchen charts photography’s invention as rooted in a change of consciousness that occurred around 1800 –a burning desire in the mind to physically hold onto fragments of reality -to make them clearly defined and fixed.

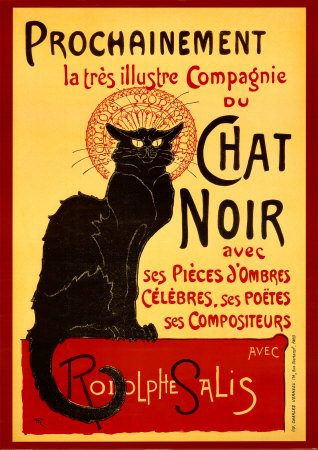

Shadow puppetry had a brief but intense revival in late 19th century Paris. The use of the term avant-garde (as an art term) was first used in a descriptive critique of an early shadow theater performance. Paris performances elevated the artform to a new level of refinement, combining storytelling, live music, lighting and art direction. Satie, Zola, Toulouse-Lautrec and Picasso were early enthusiasts of the art, which died early in the 20th century, partly due to the popularity of cinema. Modernism was developed and born in these Parisian shadow theaters, where the audience was immersed in a multi-media experience. The early origins of motion pictures alongside the shadow theater draws connections to how technology develops out of and overtakes slower art forms. Film quickly became the dominate method of storytelling (outside of books)–and would eventually see storytelling stagnate under newer and faster technologies adopted by the film industry.

Shadow puppetry had a brief but intense revival in late 19th century Paris. The use of the term avant-garde (as an art term) was first used in a descriptive critique of an early shadow theater performance. Paris performances elevated the artform to a new level of refinement, combining storytelling, live music, lighting and art direction. Satie, Zola, Toulouse-Lautrec and Picasso were early enthusiasts of the art, which died early in the 20th century, partly due to the popularity of cinema. Modernism was developed and born in these Parisian shadow theaters, where the audience was immersed in a multi-media experience. The early origins of motion pictures alongside the shadow theater draws connections to how technology develops out of and overtakes slower art forms. Film quickly became the dominate method of storytelling (outside of books)–and would eventually see storytelling stagnate under newer and faster technologies adopted by the film industry.

The Spirit of Montmartre cataloged the impact of Shadow Theater on the avant-garde of Paris: “With the help of backstage assistants who could number as many as twenty, the perfectionist Riviere was able to develop complicated and sophisticated effects of color, sound and movement for the series of over forty eclectic plays that he and his colleagues produced during the eleven years that the shadow theater existed at the Chat Noir…Over the years, thousands upon thousands of individuals viewed the Chat Noir’s shadow theater productions: bohemians, aristocrats, politicians, generals, and members of the bourgeoisie sat side by side in the Salle des Fetes with artists, writers, actors and actresses, scientists, and adventurers.”*

The revival of shadow plays in the late 19th century was a form of anti-modernism, satirizing and critiquing the bourgeoisie. A similar shadow theater revival bookends the 21st century, happening alongside technological advances and the digital age. Currently, the International Shadow Theater Center maintains connections to over 300 Shadow Theater companies worldwide and conducts an International Shadow Theater Festival held every three years in Schwäbisch Gmünd.

It’s no coincidence that the growth of spiritualism and occultism occurred alongside the development of photography, stage magic, shadow theater and other optical phenomena in the 19th century. The relationship between technology and spiritualism is a long and jointly rooted history. There is no future technology without a change in consciousness. The fast growth of video gaming and phone photography can also be related to optical desires, those tied to social needs which have now largely supplanted spiritual ones.

*The Spirit of Montmartre: Cabarets, Humor and the Avant-Garde, 1875-1905, edited by Phillip Dennis Cate and Mary Shaw, Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University, New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1996, p.66