Memory is not an instrument for surveying the past but its theater. It is the medium of past experience, just as the earth is the medium in which dead cities lie buried. He who seeks to approach his own buried past must conduct himself like a man digging.

—Walter Benjamin, Berlin Childhood

Ray Johnson has been called a mystery, an artists’ artist and visionary artist. As one of the earliest progenitors of pop art, performance, installation and happenings, he was also the founder of correspondence art, phone art, Moticos and performance nothings. Ray’s body of work has had a growing public interest and fascination since his untimely yet timed suicide, on January, Friday the 13th, 1995.

Ray Johnson with Suzi Gablik as they set up a moticos installation, autumn 1955. Photo by Elisabeth Novick.

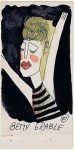

Born in Detroit on October 16th, 1927, Johnson attended Cass Tech High, where his caricatures of Hollywood starlets were popular among his classmates. These early drawings were the beginnings of Johnson’s “fan-club” satire riffs on a celebrity obsessed world — a subject that he would hold steady throughout his life. Johnson’s best friend in high school Arthur Secunda, saved his juvenilia from the trash (and in personnel letters)and each one displays how caricature, pop-culture, humor and a creatively drawn line had penetrated his art.

By combining his classmates and teachers with pop culture heroes like Betty Grable, “spy dancer” Mata Hari and the famous stripper Gypsy Rose Lee, the young Ray elevates his own middle-class life through the power of exotic imagination.–Sabastian Matthews, Messages in a Bottle: Notes of an Unlikely Curator

Often referred to as the most famous unknown artist in New York, in death, Johnson achieved a kind of fan-club immortality of his own. His highly personal art-from was transformed into miniaturized mass communication. From everyday letters, books and simplified performances, Johnson opened the borderline between his network of friends and the world, especially between what is human, humble, small and overlooked. He used alternatives to traditional exhibition —to escape and subvert the gallery system and create a thoughtful offbeat art experience, in-the-present, open-ended and free— a style and system similar to radio as theater, stand up comedy and jazz improvisation. Although he embraced a humble process (mail-art, sidewalk displays, collage) Johnson manipulated, recycled and often performed his work like a jazz artist riffing on themes commonly found in modern culture.

He meant his death by drowning as a mailing event. When he sent works of art through the mail to people as gifts, he was describing what he thought were the correct relations among people… An envelope from Ray was like a haiku, a moment of immediacy and indeterminancy, a particularly vivid moment outside the economy, outside the machinery of our culture. It was free. –Bill Wilson, Dear Friends of Ray, and Audiences of One

Johnson’s work was a parallel world that has been often compared to the internet and social media. He re-imagined art as a quick gift communication, a part of daily life—and a constant engagement that links the past, present and future into interchangeable symbols; fateful accidents, magic reversals and poetry. His books and letters were simple but intricate puzzles, jokes and riffs, self-contained miniature anti-museums; missives that questioned artistic purpose, collecting, collectors and especially the use of art, stretching it’s boundaries into poetry. Each piece was an offering commonly made for its receiver, often giving specific instructions with a response or action to follow.

I happen in my work to use words. And perhaps it’s all incorrect that these be looked at in terms of painting or creativity or beauty or whatever. It might very well just be useful objects like an automobile or a chair. And these happen to be things hanging on the wall. And what I wish — well, it would have to be a great interest — would be to try to present what goes into the making of [it.] I never used to believe in a work of art being bought.

-Ray Johnson interview with Sevim Feschi, 1968

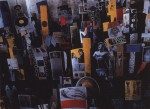

Johnson was the first artist to use pop images as appropriation art years before Warhol and the generation of pop artists. His use of Elvis, James Dean and other pop-celebrities began in the early-fifties, an outgrowth of his high-school celebrity juvenilia. In 1955, he used the neologism Moticos, as a Zen inspired name for the asymmetrical pop-art collages he made from newspapers, magazines and found poetry. These forms were organized into 3-dimensional patterns and subjects, then displayed freely in public spaces; on sidewalks and gallery lobbies of New York City. They are often referred to as proto-happenings or guerilla street art. He once described Moticos as “boxcars on a moving train” – a blurred movement and slice of time. The passage of time, was marked by the Moticos, grouped together as thin slices of moveable sculpture, glyphs reflecting the urban rhythms of culture, a portable communication, always rebuilding and ready for travel. Their installation was quick and instant, art that literally “popped-up” on the sidewalk.

Influenced by an apprenticeship under Joseph Cornell and an earlier Black Mountain College residency, Johnson worked primarily with collage, poetry and ink drawings, connecting with an ever expanding circle of artist-friends that included John Cage, Frank O’Hara, Norman Solomon, Warhol, Cy Twombly, Richard Lippold and Robert Rauschenberg. Collage was Johnson’s way of altering time and memory, using ideas and connections that could flow freely and disseminate between artists and the public quickly and informally. He connected with a small but growing circle of friends through postcards or letters, and tapped into memories (both his own and those of artists, correspondents and general culture) –a strategy that was collaborative and communal. When Johnson took Warhol for a haircut at Billy Name’s tin-foiled apartment in 1959, the silver factory era began — a world where Johnson was an active provocateur and participant.

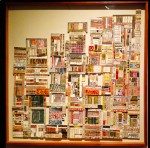

For many years the work January / February(1966) sat in the Detroit Institute of Arts’ (basement) deep freeze. Even long after his death, and covers on Artforum and Art in America, the work remained unseen. After the museum’s $158 million overhaul in 2007, it suddenly saw daylight. It had currency. Sturdy and mysterious; it looked like a maze of windows stretching across the frame, a flattened connect-the-dots sculpture to fill in yourself, a key work that sums up many of Johnson’s best ideas—a kind of open theater where memory is projected.

January/February recalls Johnson’s ’50s experiments with Moticos, built up from layers of pasted magazine pages and Bristol board, carefully cut and sanded smooth. The work takes on the form of boxes, steps, stacks of books, postcards or a secret architecture with divisions in space. It could be a library, apartment complex, windows, maps or a blueprint of the museum itself, viewed as an overhead diagram, or interior graphic. Perhaps dozens or hundreds of moticos were cut-up and recycled to make this single layered monument.

“Moticos” is an anagram of the term “osmotic,” the adjectival form of “osmosis,” which refers to the process of liquid flow between two semi-permeable membranes, and more colloquially, to the gradual process of assimilation or absorption of ideas. According to the possibly apocryphal account offered by Johnson, the term was arbitrarily picked from a dictionary by his friend Norman Soloman; yet, this word effectively evokes the idea of dynamic flow and exchange, qualities that are relevant to Johnson’s developing collage practice during this period. –Johanna Gosse, From Art to Experience: The Pourous Philosophy of Ray Johnson

January/February is covered in antiqued cardboard fragments, dashes of rubbed out color and words built up on the surface. One of the few words left whole and readable is an almost microscopic clue: undivided. The view is both macro and microcosm, desolate yet dense and overflowing with hidden information, an undivided collection of divisions, randomness and repetition, a visual Zen koan—a specialized viewing field that Johnson developed. The moticos and their reconstruction by destruction was Johnson reinventing himself –reclaiming his original vision as talisman codes. January/February is connected directly back in time to his pop mash-ups of the mid-’50s through a series of snakes and ladders, another symbolic motif that Johnson worked.

In his statement “What is a Moticos,” Johnson compares the term to a moving or standing still train-car. “The next time a railroad train is seen going its way along the track, look quickly at the sides of the box cars because a moticos may be there,” writes Johnson, “Whether the train is standing still or speeding past you, a moticos Don’t try to catch up with it. It wants to go its way. But have your camera ready to snap its picture. It likes those moments of being inside the box.” The analogy of a moticos to a train car boxes is to pages of memory — and to saving those memories: “Cut it out. Save it. Treasure it. Make sure it is in a box or between the pages of a book for your grandchildren to find and enjoy,” said Johnson.

As custodian of imagination and memory, the museum is the flip-side of life. It enables accidental communions, collisions of time in a controlled vacuum. The museum is a launching pad for alchemy, an undivided space where one can experience the life force of generations – and tap the memories of growing up beside them. The museum is a space where the material and anti-material collide, where deviant observations are allowed, outside the confines of work, home and society. January/February is a portal into Johnson’s cosmic undivided universe; a doorway into new consciousness.

All museums are a form of moticos; assemblages of collected time, touchstones of past civilizations and culture. Museums are defined not only by what they contain but by what they ignore, what is uncollected or invisibly stored in the basement. A museum is composed of layers, a collage taken from pages of memory. When thinking about objects in the museum, an alternative history takes shape, a history reborn in stillness with our own thoughts about culture and all that surrounds us, waiting to be uncovered.

A shorter and different version of this essay appears in the January 2014 edition of ArtForum.

Hello–

Who wrote this essay? I don’t see it on the Artforum website for the January 2014 issue. Any more information would be appreciated. Thank you!

I (Cary Loren) wrote the essay. I’ve included a link to the Jan. 2014, Artforum issue but its available only for subscribers. You can also reach me at: bookbeat@aol.com

Denny is alive and well!

He did not pass away and is an excellent artist and a good person with a big heart

No, I am sorry but he passed a few years ago.

You are a dumb ass, Ray Johnson was a real mail artist. That name is not fake nor is it an alias. Learn your art history!