This Strange Necessity: On Rebecca West and James Joyce

What is the meaning of this mystery of mysteries? Why does Art matter? And why does it matter so much? What is this strange necessity?

–Rebecca West

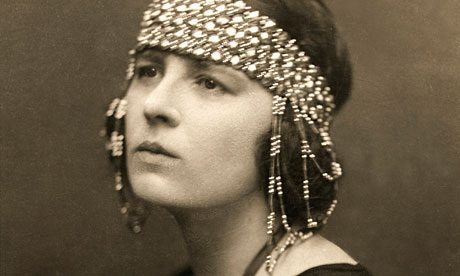

Rebecca West, 1920s

In her book-length essay The Strange Necessity (1928) author Rebecca West (1892-1983) observed how the creative act was a holistic and natural force. West proposed that in the act of creating, the artist had merged with nature, and was connected to the natural world. West’s metaphor for the artist is a tree. “Determined and exclusive as the tree’s intention of becoming a tree, and by passing all his material through his imagination and there experiencing it,” writes West, “He [the artist] achieves the same identity with what he makes as the growing tree does.”[1]

The Strange Necessity claims the process of artistic creativity rises from a biological necessity, an unstoppable passion connected with primal desires. The artist, she claims, is never in absolute control of creation but is fulfilling a natural process bound up within life. The “strange necessity” West explores is also the spiritual impulse—an intuitive and higher realm beyond thought or emotion, alive in all creative action. West identifies a fundamental unity between art and experience, where the creation of art is an engagement with life—a process that can be viewed as transcendent—connected to spiritual purpose and the sublime.

The Strange Necessity, first edition, 1928

The Strange Necessity is a meditation on the creative act. In her concluding pages, West shifts to the exaltation and spiritual function a work of art performs on the individual; a relationship to art, she believes, that borders on the sexual. “This crystalline concentration of glory,” writes West, “this deep and serene and intense emotion that I feel before the greatest works of art… overflows the confines of the mind and becomes an important physical event…Is this exaltation the orgasm, as it were, of the artistic instinct, stimulated to its height by a work of art.”[2] West’s statement is reinforced by an often quoted Gertrude Stein-ism, that Literature—creative literature—unconcerned with sex, is inconceivable.

This physical manifestation of art can be sensed in the sublime landscapes of Frederic Church and J.M.W. Turner, the spatial abstraction of Kandinsky, the genius of Bach and Mozart, or the poetry of Melville and Poe; works that commune with the soul and enter the body as a metaphysical construct. This attraction of the physical and sublime was fundamental in the development of modernism, written into expressions of abstraction, cubism, Jazz, avant-garde poetry and fiction; attributes of the mind in free exaltation. Kevin Birmingham, in The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses, writes, “Joyce had been searching for an epiphany in a person. He thought the worlds radiance could emerge from an erotic connection with a woman who became in his mind an amalgam of women he had seen in Paris and Nighttown, and the fact that she didn’t exist made it easier to sentimentalize her.”[3]

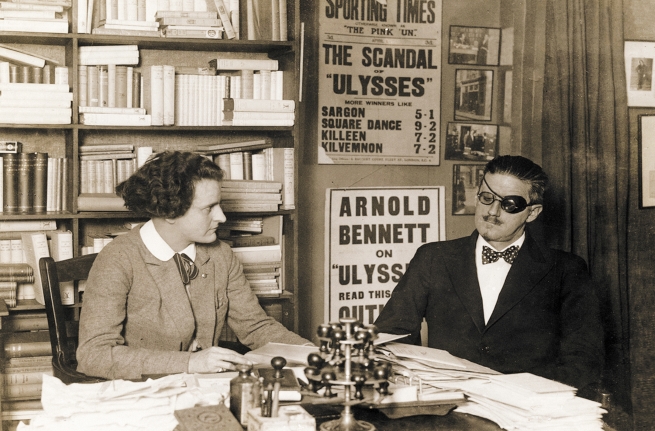

Sylvia Beach and James Joyce at Shkespeare and Company

Mirroring Ulysses, West portrays a single summer’s day in Paris given to investigate the novel. She spends the day thinking about the book while strolling through the city. West opens her essay just after entering Sylvia Beach’s bookshop where she buys a copy of Joyce’s Pomes Penyeach. Beach’s bookshop, Shakespeare and Company, was the epicenter of expatriate life in Paris and the physical origin of Ulysses, where it first was published by Beach in 1922. By the late twenties, after eleven printings of the book, and charges of obscenity against the novel, Joyce’s reputation grew to majestic heights and Shakespeare and Company grew alongside it, becoming a central salon of literary modernism.

A doubling of art and life is at the core of Ulysses which occurs in a single day in Dublin. A cornerstone of modernist writing, the novel spreads out into a vast labyrinth of word play, black humor, and subversion. “A rich texture of interpenetrating mental and physical worlds,” writes Derek Attridge.[4] Exploring Dublin on this day, is the character Leopold Bloom, and Joyce’s alter ego: Stephen Daedalus. It was in Paris, in a decrepit one bedroom five-story walk-up without water or electricity (found for Joyce and his family by Ezra Pound), where Joyce finished writing the last chapters of Ulysses, and wrote the entirety of his final book Finnegan’s Wake.

This entwined critical process pivots between art and life, walking and thought, a process deep at work in Ulysses, as well as in Strange Necessity, an adventure set off after browsing in a bookstore. West recalls Paris in flowing images mirrored against thoughts about Ulysses. Each of these left-bank reflections are compounded into a hall of mirrors bouncing from incidents read in Ulysses returning back to her physical world, merging fiction and reality into free-form play and critique.

As West strolls down the Rue de Rivoli, she observed the towers of Notre Dame, so solid and firm, and began comparing them to Leopold Bloom, whom West first describes as “A court jester, a Shakespearean fool.”[5] There are two sections of Notre Dame, West points out; its façade of two towers, “richly carved to suggest the elaboration of life which will inevitably co-exist with its elevation, sturdily proportioned to suggest that the elevation is mechanically possible, can endure in the real world…and under the towers are the naves and the transepts and the baptistery, and the whole body of the church.”[6] West maintains that Bloom is “one of the greatest creations of all time,” but that his façade, and character lacks the inner structure and beauty that makes Notre Dame sublime.

Pomes Penyeach, first edition

Joyce never took public notice of the essay, but in a letter sent to Harriet Weaver, his benefactor in 1928, Joyce nearly blind, wrote, “About fifty pages of Rebecca West’s book were read to me yesterday, but I cannot judge until I hear the whole essay. I think that P.P. [Pomes Penyeach] had in her case the intended effect of blowing up some bogus personality and that she is quite delighted with the explosion.”[7] Joyce later wrote an oblique parody diminishing West and Strange Necessity within Finnegan’s Wake. A poisoned-pen revenge artist, Joyce would often aim his vitriol at perceived enemies and other’s when he felt betrayed. The following Finnegan’s Wake passage is thought to be a portrait of West:

She was just a young thin pale soft shy slim slip of a thing then, sauntering, by silvamoonlake and he was a heavy trudging lurching lieabroad of a Curraghman, making his hay for whose sun to shine on, as tough as the oaktrees (peats be with them!) used to rustle that time down by the dykes of killing Kildare, for forstfellfoss with a plash across her. She thought she’s sankh neathe the ground with nymphant shame when he gave her the tigris eye! O happy fault! Me wish it was he! You’re wrong there, corribly wrong! Tisn’t only tonight you’re anacheronistic! It was ages behind that when nullahs were nowhere, in county Wickenlow, garden of Erin, before she ever dreamt she’d lave Kilbride and go foaming under Horsepass bridge, with the great southerwestern windstorming her traces and the midland’s grain-waster asarch for her track, to wend her ways byandby, robecca or worse, to spin and to grind, to swab and to thrash, for all her golden lifey in the barleyfields and pennylotts of Humphrey’s fordofhurdlestown and lie with a landleaper, wellingtonorseher. . . . .

[8]

West’s essay was one of the first reviews of Ulysses–a personal ‘semi-fictional’ reporting of Ulysses, which aired her mixed emotions of the work she condemned as weak because of Joyce’s sentimentality, but in the end, she considered it a work of art. “I claim,” West writes, “that the interweaving rhythms of Leopold Bloom and Stephen Daedalus and Marion Bloom make beauty, beauty of the sort whose recognition is an experience as real as the most personal experiences we can have, which gives a sense of reassurance, of exultant confidence in the universe, which no personal experience can give.”[9]

West creates a dualistic vision in her critique of Ulysses. She is personally affronted by the dinginess of Dublin, while praising Joyce’s genius and the beauty of the left bank. “Except when the book is at its greatest,” writes West, “I resent being rapt into the squalor of Dublin; I detest the sentimentality and the subjugation to simple and groundless and unappealing fantasies which are the special weakness of Mr. Joyce,”[10] West goes through an inventory of letters, sights and objects within her life and inside Ulysses which become “bridges” to her illumination into works of art. “[Joyce,] who can pour his story into the mould of the Odyssey and do it with such scholarship that the ineptitude of the proceedings escapes notice, who pushes his pen about noisily and aimlessly as if it were a carpet-sweeper, whose technique is a tin can tied to the tail of the dog of his genius, who is constantly obscuring by the application of arbitrary values those vast and valid figures in which his titanic imagination incarnates phases of human destiny.”[11]

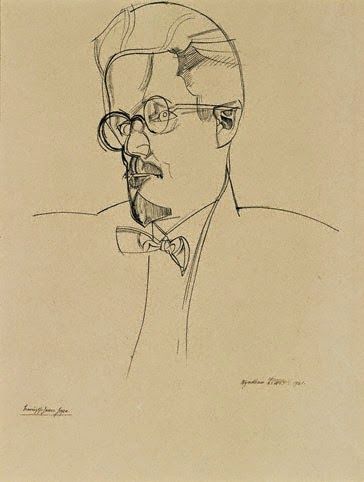

Sketch of James Joyce by Wyndham Lewis, 1921

Coming to terms with this constant duality is a paradox for both authors. “Whatever mechanism may be working works mysteriously,”[12] writes West. In a letter to Joyce’s biographer Richard Ellmann, West explains she was writing a semi-fictional essay (in the style of French critic Edmond de Goncourt) “intended ‘to show the power of James Joyce breaking into a mind unprepared for it.”[13] Joyce’s misreading of West was unfortunate, but she did create a way to penetrate all works of art in A Strange Necessity.

The concept of ‘fun’ is another method West proposed in understanding art. “What gives us fun is usually remarkable for its high horse-power,” writes West. “It is the product of a powerful nature that has been able to form an interesting and intricate fantasy or which is able to prosecute with spectacular vigour the effect to make the fantasy and reality match.”[14] West negotiates the beauty of Paris and the darkness of Dublin shedding light on her quicksilver consciousness.

The importance of a location for culture to grow is explored by West at Shakespeare and Company, Notre Dame, the Louvre and along the Rue de Rivioli; locations that stirred West’s mind into ruminating on Ulysses, a novel deeply rooted in place. The brothels of Nighttown in Dublin, as well as the city of Paris also became the nexus of inspiration for Ulysses. These urban locations began to form a new kind of consciousness within Joyce, an interior space he began shaping with his penny notebooks into a novel. The sense of place is so informed and solid in Ulysses, and its linchpin literary reputation is so interred, that travelers from around the world descend on Dublin every June 16th to follow the footsteps of Leopold Bloom. Known as Bloomsday, it commemorates the first outing Joyce had with his future wife Nora Barnacle and the day Daedalus in Ulysses sets out for Dublin in 1904.

West takes the example of Ulysses as a motivating pendulum in the arts. The passage of a spiritual or natural transformation from one artist to the next, often occurs between written and visual worlds. Further down the Rue de Rivoli, West reflects on an Ingres painting she saw in the Museum of the Louvre. “How in the world could two artists so entirely unlike in every way as Ingres and James Joyce cause a like emotion?” West asks, “And this emotion is not merely an isolated incident, not merely a discharge of psychic energy caused by an unusual stimulus. It is part of a system; it refers to one of the rhythms of which we are the syntheses.”[15] The fractured, fragmented time and spaces West enters through the essay, could also be said of Picasso and Braque’s cubist paintings; radical images set in multiple points of time, a device also mirrored in the writings of early modernists Knut Hamson, Gertrude Stein, Isak Dinesen, and Virginia Woolf.

The body and sexuality have an effect within all the arts, however, the metaphysical and spiritual are commonly downplayed. The opening of early nineteenth century America to its vast resources and its unending expansion has been a source of this nation’s spiritual tensions, uneasiness, greed and desires. Conditions of genocide, racial divisions, repression and the destruction of land and resources once opened and exploited are types of decay that can only be reconciled by a spiritual solution; a complete transformation rooted in love and justice. “Art is at least in part a way of collecting information about the universe,”[16] said West.

Rebecca West, 1920s

West declared the United States as part of a political necessity; a country of action and belief born out of a life or death situation. A Nation that came into existence because of a necessity for freedom, a grand idea continually tested and held together by a thread.

Contained in the kernel idea of spiritual America is unbounded space; a resource of freedom without restraint, an idea that serves the arts and the areas in which art flourishes. Melville’s Moby Dick holds a similar form as the Apollo space mission, or a romantic walk through Paris or Dublin. The Westward-ho drive mythologized in John Wayne movies as a “manifest destiny,” is a white-washed political truth ignoring racial bigotry, slavery, Native-American genocide, and the poison of violence and hatred that are tied hand-in-hand to the pursuit of happiness and a nation’s birth. It is only through the lens of art we learn to see and feel the truth.

“Art is not a luxury, but a necessity,” writes West. “It is not merely pleasant for me to read Ulysses and to see Ingres’ portrait of the young man in a snuff-coloured jacket, it is necessary that I should do so… Art is not arbitrary, but is determined to the minutest details.”[17] We use art in many ways-but most importantly our exposure helps us recognize what “the pursuit of happiness” is and why that’s important and vital. West created The Strange Necessity not just an answer to help define art, but to form the questions that art poses within us. West brought this together in the form of a fictional critique, a way of aesthetic thinking—and a synthesis of emotional and critical thought.

–Cary Loren, revised 2012

[1] Rebecca West, The Strange Necessity (Doubleday, New York, 1928) p.7

[2] The Strange Necessity, p. 210-211

[3] Kevin Birmingham, The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses ( Penguin Press, 2014) p.27

[4] Derek Attridge, editor, James Joyce Ulysses: A Casebook (Oxford University Press, 2004) p.5

[5] The Strange Necessity, p.35

[6] The Strange Necessity, p.37

[7] James Joyce quoted in Richard Ellmann’s James Joyce (Oxford University Press, 1959) p. 618

[8] James Joyce Finnegan’s Wake (Random House, 1939) p.202-203

[9] Strange Necessity, p.44

[10] Strange Necessity, p.46

[11] Strange Necessity, p.52

[12] Strange Necessity, p.50

[13] Selected Letters of Rebecca West,(Yale University Press, 2000) p. 618

[14] Strange Necessity, p.61

[15] Strange Necessity, p.55

[16] Strange Necessity, p.88

[17] Strange Necessity p.191-192