To take photographs means to recognize—simultaneously and within a fraction of a second—both the fact itself and the rigorous organization of visually perceived forms that give it meaning. It is putting one’s head, one’s eye and one’s heart on the same axis.

— Henri Cartier-Bresson

Take care of all your memories… for you can not relive them. -Bob Dylan

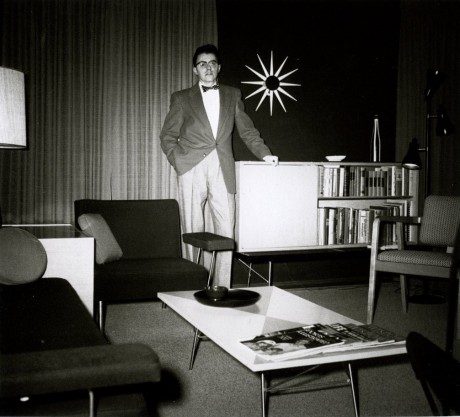

From poetic and humorous recordings of family life and urban landscapes to his surprising tabletop conceptions, Bill Rauhauser’s photography has always been stamped with clarity of thought, gentle beauty and an eye for composition. His decades long love affair with Detroit, modernism, photo history and the organization of forms and their refinement is an inspiring tale. He is at the age of 93, still questioning and recreating himself as an artist.

From poetic and humorous recordings of family life and urban landscapes to his surprising tabletop conceptions, Bill Rauhauser’s photography has always been stamped with clarity of thought, gentle beauty and an eye for composition. His decades long love affair with Detroit, modernism, photo history and the organization of forms and their refinement is an inspiring tale. He is at the age of 93, still questioning and recreating himself as an artist.

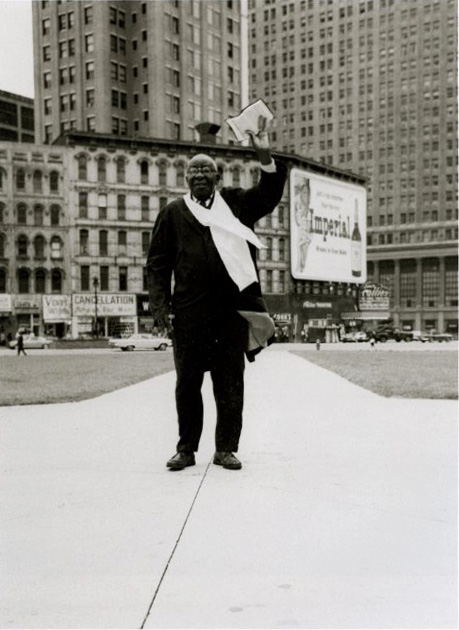

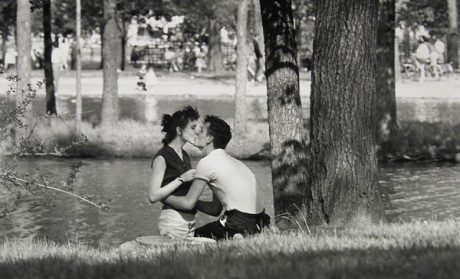

There’s nothing sentimental, passive or decorative about Rauhauser’s street work yet they contain a romantic and passionate core, all beautifully rendered black and white images, each a small poignant story. Some of the best work is risky, unconscious, snapshot driven, yet always carefully composed, implanted with the memories and respect for the city and its culture. The urban environment is the star in most Rauhauser photographs.

Detroit has become a favorite location for photographers in the recent past, chosen as the symbolic and literal center of the post-industrial wasteland. Many books have documented its magnificent ruins. Rauhauser’s investigation was a prelude to the ruins, a map before the crime-scene, familiar territory for anyone brought up in Detroit in the 1950s or 1960s.

There is something fatlly romantic about an urban photographer in the mid-1950s wandering freely throughout Detroit. Rauhauser’s practice both coincided and sometimes mirrored the beat era mythology that grew around the wandering figures of Robert Frank and Jack Keroauc, whose On the Road was published to a sensational response in 1957. Being anchored to Detroit in the 1950s was a much less fashionable and frenetic situation for Rauhauser, but perhaps a more truthful one. He was stuck in the quintessential American city, the crucible and furnace of Fordism, where the struggles of race and class were played out in everyday life.

Rauhauser’s snapshot of a three-some on a bench was an image included in the 1955 ‘Family of Man’ exhibition.

After describing a visit to Henri Cartier-Bresson’s exhibition at MOMA in 1947, as a “revelatory” one, Rauhauser quickly realized that his life’s passion and career path would soon be devoted to photography. The idea of eternity frozen in a photograph – life organized and contained in a single ‘Decisive Moment’ rang true for Rauhauser, and he began spending his free time on the streets with a Leica 35mm rangefinder (the same camera preferred by Cartier-Bresson).

In 1955, a photograph by Rauhauser (Three Figures on a Bench) was chosen by Edward Steichen for his “Family of Man” exhibition, one of the most successful and viewed photo exhibits in history, seen by over nine million people. Rauhauser took that as an encouraging sign and he continued his work with renewed vigor. 1955 was also the same year Robert Frank began his cross-country photo project that would result in the groundbreaking project “The Americans” – a milestone in photo history. Frank’s snapshot aesthetic held a fascination for Rauhauser, who was already practicing those same methods himself on the streets of Detroit.

* * *

Rauhauser has often referred to himself as a flânuer, a wandering urban observer, sampling and documenting the rhythms and pace of the city. The flânuer was a term popularized by Charles Baudelaire to describe the slow city-gazing, 19th century window-shopping dandy of his time – the romantic urban wanderer. Baudelaire admired photography’s documentary nature but also despised and thwarted its fine art applications. In his essay On Photography of 1859, he describes the dual nature of photography and where he saw it headed; “If photography is allowed to supplement art in some of its functions, it will soon have supplanted or corrupted it altogether, thanks to the stupidity of the multitude which is its natural ally. It is time, then, for it to return to its true duty, which is to be the servant of the sciences and arts… Let it rescue from oblivion those tumbling ruins, those books, prints and manuscripts which time is devouring, precious things whose form is dissolving and which demand a place in the archives of our memory—— it will be thanked and applauded.”[i]

The book Bill Rauhauser 20th Century Photography in Detroit is a treasure trove for what it preserves of Motor City life, especially the era following World War II, when streets were filled with vendors, shoppers and energetic activity of all kinds. Rauhauser concentrated his walks along Woodward Avenue, Mid-town (Wayne State University), the riverfront, Belle Isle, and took to documenting small working class homes and the city’s architectural gems. The vibrancy of those times marks a stark contrast to how the fortunes of the automotive capital would slowly unravel.

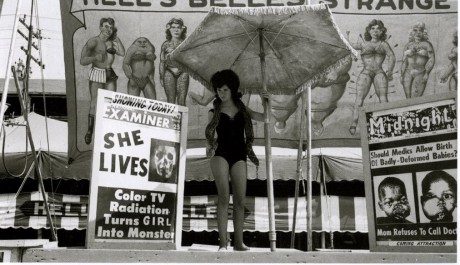

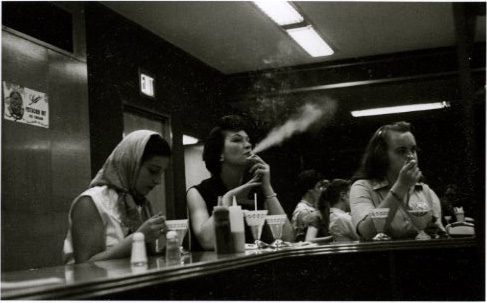

In over 300 black and white images we journey with Rauhauser in a city overflowing with consumerist euphoria, determination and grit –scenes abundant with immediacy and excitement. The photograph Sander’s Lunch Counter, Woodard Avenue, Detroit shows a group of three women enjoying ice-cream on a typical hot summer’s day, the middle figure blowing a frozen funnel of cigarette smoke into the air, a scene most Detroiters of a certain age can identify with –and there are many others, like the series of the Michigan State Fair sideshow barker’s and their sexy but dangerous looking carnival gals. Street preachers, rushing lunchtime office workers, newsstands, fruit vendors, street cleaners, gamblers, musicians, barbershops, students, bikers and fashionable women fill the book with a timeless lost-world glow. The photos are presented with little or no captions, but they will gain in awareness and vibrancy over time, true vessels of how we saw ourselves and lived in Detroit before the departure of industry and the apocalypse of ruins took its toll.

The book collects many memories, scenes from a past gone-to-dust and a history belonging to all who’ve lived it or care to see. There are many isolated and lonely figures; seniors, park-bench warmers, workers, beggars, pimps and bums; the outsiders of society found in daily encounters that break down and disrupt “normal” social order – gatherings and crowded street scenes dissipate into fragile moments of reflection and despair, slices of life’s existential sadness – tiny miracles caught in time.

* * *

There’s a wealth of material to soak in -amazing jaw-dropping images that stop you in your tracks. Here’s mid-century Motown, alive with a variety of activities, barbershop rituals, bus-stop queues and swaggering soul brothers and sisters. One small section devoted to Detroit auto shows in the 1960s is one of the book’s strongest highlights. Young models with exaggerated flip hair-dos, million-dollar smiles, mini-skirts and go-go boots light up the Cobo Hall displays selling sex and sizzle alongside the latest Detroit muscle cars.

This decades-long self-assignment aligns well with many other urban photo projects such as Atget’s life study of the monuments and beauty of Paris, Arnold Genthe’s Chinatown in turn-of-the-century San Francisco and the New York Photo League’s gritty documentation of New York City in the 40s and 50s. Rauhauser’s work clearly shows the lighthearted sense of improvisation and quick thinking he brings to street photography, which is the main attraction filling most of the book. It should remain the standard reference for displaying Detroit in classic mid-century for years to come.

Rauhauser’s street scenes are varied in technique and subject matter, ranging from posed and thought out compositions, to comical, uninhibited, and voyeuristic off-the-hip shooting. Many photographs are the result of strong technical ability matched with careful planning and dumb chance. The Zen-like presence of the photographer is there to see and think ahead, becoming invisible to his surroundings and subject. For the most part his subjects are caught off-guard and unaware of the camera. Rauhauser’s key distinction is a graphically charged and constructive eye that builds a photograph from layers of physical reality and his desire (the subject matter) against the balanced dispersal of light and darkness.

Rauhauser’s street scenes are varied in technique and subject matter, ranging from posed and thought out compositions, to comical, uninhibited, and voyeuristic off-the-hip shooting. Many photographs are the result of strong technical ability matched with careful planning and dumb chance. The Zen-like presence of the photographer is there to see and think ahead, becoming invisible to his surroundings and subject. For the most part his subjects are caught off-guard and unaware of the camera. Rauhauser’s key distinction is a graphically charged and constructive eye that builds a photograph from layers of physical reality and his desire (the subject matter) against the balanced dispersal of light and darkness.

Bill once said, “I see in black and white.”- a vision used with good effect alongside the complexity of moving subjects and architectural backgrounds. Bill also see’s in shades of desire; a pretty figure, sophisticated well-dressed ladies, women in bathing suits, leggy dancers, snake-charmers, sexy backsides, young women smoking, modeling and performing – a veritable parade of beauties and sexy delights!

* * *

Several images quote important historic photographs, an ability that came naturally and perhaps unconsciously to Rauhauser with his deep knowledge of photo history. There’s the Atget-like side view of a man in thick boots wheeling a heavy loaded cart of cardboard across the street (p.92) looking plucked from another century and several movement-freezing shots echoing Martin Munkacsi; (p. 83, 143) who once said, “all great photographs today are snapshots.” Rauhuaser’s image of four young blacks on the beach of Lake Michigan (p.114) harken back to the iconic Munkacsi image, Black Boys ashore Lake Tanganyika taken in 1931, an image Cartier-Bresson credited “as the only photograph to ever inspire me.”

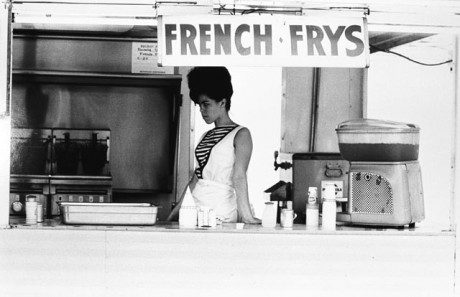

Overloaded streets filled with humanity combined with Rauhauser’s eye for female beauty bring to mind Gary Winogrand’s “Women are Beautiful” series ; (p.134, 148, 155, 178, 213) and the flattened almost painted looking urban cityscapes of Aaron Siskind; (p. 100, 130, 164, 194) or the pool-hall greasers of Danny Lyon (p. 62, 209, 219) and the urban lunch counters of Robert Frank; (p. 60, 81). His image of the tough bee-hived French Fry Girl from either Bob-lo island or the State Fair is an unforgettable iconic 1960s portrait

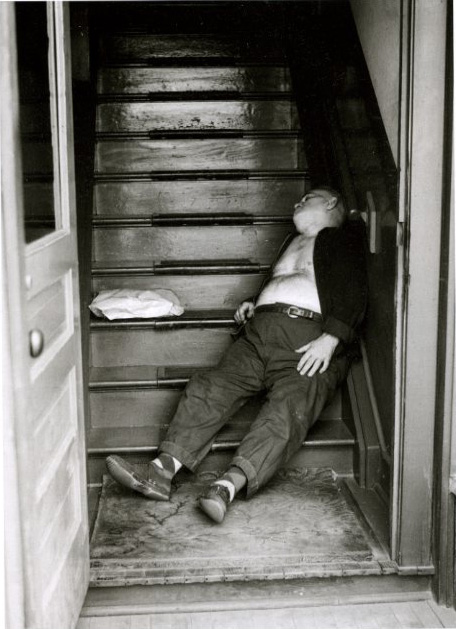

Overloaded streets filled with humanity combined with Rauhauser’s eye for female beauty bring to mind Gary Winogrand’s “Women are Beautiful” series ; (p.134, 148, 155, 178, 213) and the flattened almost painted looking urban cityscapes of Aaron Siskind; (p. 100, 130, 164, 194) or the pool-hall greasers of Danny Lyon (p. 62, 209, 219) and the urban lunch counters of Robert Frank; (p. 60, 81). His image of the tough bee-hived French Fry Girl from either Bob-lo island or the State Fair is an unforgettable iconic 1960s portrait . Visual puns and mirrored images abound like the ridiculous toy-car parade Shriner’s convention, Detroit 1978, (p.184), the odd man at the State Fair unconsciously mimicking a circus banner behind him (p.227) or the Weegee-like bum sleeping off his drunk in the doorway: Cass Avenue, Detroit (p.103).

. Visual puns and mirrored images abound like the ridiculous toy-car parade Shriner’s convention, Detroit 1978, (p.184), the odd man at the State Fair unconsciously mimicking a circus banner behind him (p.227) or the Weegee-like bum sleeping off his drunk in the doorway: Cass Avenue, Detroit (p.103).

* * *

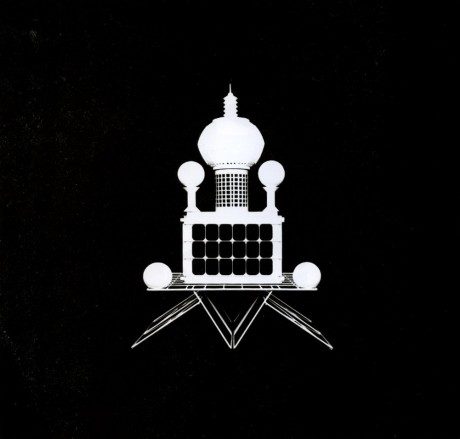

An unusual still-life series Rauhauser began in late 1960s became known as the “Object Series”. Dejarlais notes in the book’s introduction, “He purposely photographed objects that were invisible to society because of their daily functional use…using a 4×5 view camera he aimed for intense clarity and lit them for optimal revelation of detail…” He furthered these experiments by exploring object abstractions in a series of totally wild and comic black  and white architectural objects, the Egyptian titled Temples and Tombs series –a totally unique body of work in the history of photography, one he discovered by himself and owns –a series created out of found materials and discarded kitchen utensils. These fantastical high contrast works were produced sometime in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a humorous conceptual and creatively jarring body of work, perhaps an antidote and well thought out minimalism to bookend his earlier street photography.

and white architectural objects, the Egyptian titled Temples and Tombs series –a totally unique body of work in the history of photography, one he discovered by himself and owns –a series created out of found materials and discarded kitchen utensils. These fantastical high contrast works were produced sometime in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a humorous conceptual and creatively jarring body of work, perhaps an antidote and well thought out minimalism to bookend his earlier street photography.

The still life constructions were extensions of the photographer’s passion for architecture (his first profession) and are non-manipulated, experiments in free-form expression. The Temples and Tombs series are self-contained utopian worlds, surrealist M.C. Escher-like post-objects, (almost a reversal or inversion of documentation). The series developed at a time when it was becoming more difficult to work in the street. By the 1980s privacy issues became dominant and the streets were dangerous. Rauhauser explained that with the still life work, he went into himself and pushed the straight “truth telling” aspect of photography to an extreme edge. The Temples and Tombs were an answer to an exit, analytic fragments of truth found in geometric abstraction, like something Frank Ghery would make from crumpled wastepaper. They are deceptively clever tabletop fantasies – chaotic yet ordered, strange and alien perception puzzles of pure form constructed from common everyday kitchen utensils.

Rauhauser’s object series and still lifes are relatives to Marcel Duchamp’s revolutionary notion of the readymade[ii]. By isolating the found object, removing it from its normal usage and understanding, Duchamp wished to challenge the viewer and what we accept as works of art. Duchamp presented the bicycle wheel, urinal, bottle rack and the snow shovel – the everyday object as some of the first minimalist artworks – what he called “a form denying the possibility of defining art”.

Rauhauser’s object series and still lifes are relatives to Marcel Duchamp’s revolutionary notion of the readymade[ii]. By isolating the found object, removing it from its normal usage and understanding, Duchamp wished to challenge the viewer and what we accept as works of art. Duchamp presented the bicycle wheel, urinal, bottle rack and the snow shovel – the everyday object as some of the first minimalist artworks – what he called “a form denying the possibility of defining art”.

Where Duchamp wanted to go against the grain and destroy “retinal art” with his readymade sculptures, Rauhauser emphasized the beauty and aesthetics of simple objects and common sculptural form; the baseball, derby hat, music stand, ruler, rain boot, transistor radio tube, etc., the everyday objects he was attracted to for primarily aesthetic and functional reasons – objects whose “form followed function.” These were then presented as purely clean and flat minimalist “retinal art” – a modernist reversal of Duchamp’s approach. The isolation of the object became a commonly used devise that would influence book and graphic illustration to a staggering degree by the early 1990s. Bill’s fabricated imagery fits well into the postmodern mesh of David Levinthal, Sandy Skoglund and many others. Through a careful choice of objects linked in a self-referential index – Rauhauser’s choice of forms also register as signs and symbols for the photographer’s visual autobiography.

The book’s lack of annotations and captions is a mystery, a flaw that should be fixed in a later printing. The dark grey chapter headings are abrupt and an intrusive design beside the photos, upsetting the flow of the book. The overall size is about 8.5 x 11″ and is overly generous with photos in a short span, over 300 images appear in 311 pages. The paper is of good quality with almost no bleed-through and a soft varnish added to the photos which have a good tonal range and appear printed in tri-tone or full color. The decorative glossy cover is a great graphic of a summertime parade down Woodard Avenue with the world’s largest American flag flapping on the side of the Hudson’s department store, a female photographer is seen shooting her family, with her prominent ass in the foreground. The book design is functional, but could be improved with a looser, less crowded layout and little more research for the captions.

A 30 page introductory text by Mary Dejarlais gives a close look at Rauhauser’s history and background, his formation as an artist and educator, from his beginnings in Detroit’s Silhouette camera club to his current adoption of digital photography. Dejarlais lays out the influences and histories that informed Rauhuaser’s photography and thought, including his friendship with photo dealer Tom Halsted and central figures Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank and film theorist Siegfried Kracauer.

Dejarlais’ introduction also makes clear Rauhauser’s contributions to photography and the city. Over the course of five decades many area students (now professional photographers) had taken Rauhauser’s classes at the Society of Arts and Crafts, later the College for Creative Studies (CCS). As a teacher and photo collector he exposed students to firsthand examples of famous photo works, originals he brought into the classroom. In1964, Rauhauser opened Gallery Four, one of the first galleries in the US devoted exclusively to photography. He was also responsible in the early 1960s for bringing the attention of collecting and appreciating photography as an art-form to the Detroit Institute of Arts, one of the first national museums to display an interest in the medium, an interest sparked by Rauhauser’s questioning the museum about the medium, forcing them to address it.

Dejarlais’ introduction also makes clear Rauhauser’s contributions to photography and the city. Over the course of five decades many area students (now professional photographers) had taken Rauhauser’s classes at the Society of Arts and Crafts, later the College for Creative Studies (CCS). As a teacher and photo collector he exposed students to firsthand examples of famous photo works, originals he brought into the classroom. In1964, Rauhauser opened Gallery Four, one of the first galleries in the US devoted exclusively to photography. He was also responsible in the early 1960s for bringing the attention of collecting and appreciating photography as an art-form to the Detroit Institute of Arts, one of the first national museums to display an interest in the medium, an interest sparked by Rauhauser’s questioning the museum about the medium, forcing them to address it.

* * *

Rauhauser has worked a lifetime in semi-isolation (a common situation in Detroit), but its one of the aspects he most enjoys. Detroit allowed him the freedom of anonymity, of walking the streets unfettered and for many years the city proved to be a trusted canvas and muse. He has not spent his time searching for exhibitions or promoting his work outside the city (even though there are few opportunities in Detroit for exhibiting or receiving critical feedback). He works along self-imposed rules, free to explore anywhere his imagination takes him.

When thinking of Rauhauser’s street project, I’m reminded of the quietly eccentric and stoic Eugene Atget (1857-1927), a photographer who witnessed and documented the working classes alongside the 19th century grandeur and transformation of Paris, lugging his heavy view camera across the city photographing beggars and prostitutes to regal palaces and elegant parks. Atget was unrecognized by the public but enthusiastically followed and collected by a small group of surrealist artists who eventually saved his work from certain destruction. Images taken by Atget now construct our view and how we think about Paris from the late 1890s and early 1900s. They are a transformational archive.

Bill Rauhauser 20th Century Photography in Detroit is not the glossy hallmark tour of the Motor City you might expect. The look is gritty but sincere, a survey across a sixty-year arc of Detroit images, from its industrial peak to its gradual decline. It’s raw do-it-yourself journalism of the common man, an urban spectacle and a private diary of the past, one photographer’s long term affair with photography, photographic history and Detroit, and is unlike anything published on the city before. Rauhauser is a stealthy, acute observer and flânuer of daily life, a masterful sage in our midst.

Bibliographic Coda

Just over 10 years ago, after Bill Rauhauser’s retirement from CCS, he began to seriously collect and organize the body of his photographic work. These reflections become a source of renewal for the photographer who has made a public offering in the form of books and donations of artwork. Major collections of his photographs now reside in the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Burton Library in Detroit. Soon after the publication of 20th Century Photography in Detroit, a man in the audience during Bill’s presentation at the Book Beat, purchased an extra copy for his niece, a curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. MoMA soon showed an interest in purchasing works and were recently given a donation of silver prints by Rauhauser for their permanent collection.

Bill Rauhauser 20th Century Photography in Detroit (2010) is the most comprehensive monograph of Rauhaser’s work to date. It also compliments several other books he produced and helped to publish over the past decade; Detroit Revisited (2000) with photographer’s John Thomas Baldwin and Gene Meadows, text by Mary Dejarlais, Bob-Lo Revisited (2003) with text by Martin Magid, Detroit: Auto Show Images of the 1970s (2007) and Beauty on Detroit Streets (2008) text by Mary Dejarlais. All should be known to anyone with an interest in photography, urban studies and the history of Detroit. Rauhauser and Dejarlais recently formed a new joint publishing partnership named Cambourne Publishing and we eagerly look forward to future volumes.

For the past decade, since retiring at CCS, Bill’s been leading a photo discussion group with local professional photographers and educators. At 95, Bill is still actively engaged in photography projects. He’s been working on a book of his Circus and side-show photos with photographer Carlos Diaz and another book project that studies the objects and concept of kitsch –a project that grew out of his photo discussion group. Rauhauser is an artist of deep integrity who has redefined age by continually staying active, reinventing himself, always learning and sharing that knowledge with his friends and colleagues. We are grateful and honored to have him with us still creating, exhibiting and sharing his knowledge.

Last Note: The famous Three Figures on a Bench photo shown at the beginning of this article was later appropriated and cast in bronze by another artist. It was a life-sized replica bronze of the photo, except from the front view it showed the figures engaged in sex, but that’s a story for another time.

[i] Charles Baudelaire, On Photography, Salon of 1859 http://www.csus.edu/indiv/o/obriene/art109/readings/11%20baudelaire%20photography.htm

[ii] on the readymade: Introduction, ToutFait Towards a Definition at http://www.toutfait.com/unmaking_the_museum/introduction1.html

Really brilliant piece of writing about one of our major artists. Hope everyone reads it.

Thank you Vince, much appreciated – Happy New Year!

Wonderful article. I must get his book. Looking back at my late 70’s college I realize how fortunate I was. I was not a photography major at CCS but Bill was one of the best teachers I had there. He taught me more about composition, texture, contrast and gave me a love of Black and White. I ended up taking enough Photography classes to have a minor. I have never looked at the world the same.