“Hordes of women and battalions of men of the most widely differing ages can testify to her great gift for friendship, to a love of mischief which never deserted her even in her declining years, to the way in which, sitting at a table with vodka and zakuski, she could be so funny that everybody fell off their chairs from laughter.” ~~Nadezhda Mandelstam

“Hordes of women and battalions of men of the most widely differing ages can testify to her great gift for friendship, to a love of mischief which never deserted her even in her declining years, to the way in which, sitting at a table with vodka and zakuski, she could be so funny that everybody fell off their chairs from laughter.” ~~Nadezhda Mandelstam

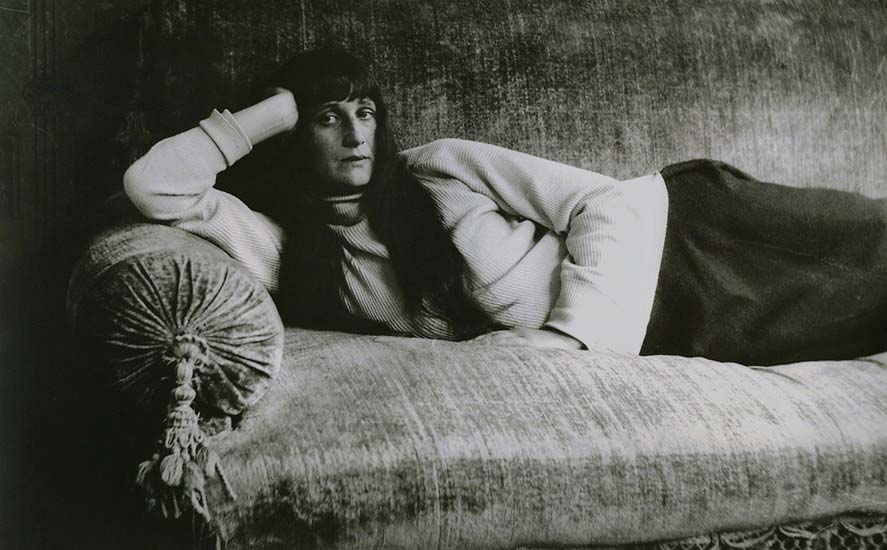

Anna Akhmatova was one of the greatest and most influential of Russian poets and was an icon of the 20th-century. She was also a symbol of political resistance, survival and the poetic imagination during Stalin’s reign of repression and terror. Her work shed the baggage of symbolism and is characterized by simplicity, precision, and a devoted attention to the wonders of nature, love, and in later work the political repression of the Soviet Union. In her poem ‘The Willow’ she connects her childhood and youth to its weeping branches:

And I grew up in patterned tranquillity,

In the cool nursery of the young century.

And the voice of man was not dear to me,

But the voice of the wind I could understand.

But best of all the silver willow.

And obligingly, it lived

With me all my life; it’s weeping branches

Fanned my insomnia with dreams.

And strange!—I outlived it.

There the stump stands; with strange voices

Other willows are conversing

Under our, under those skies.

And I am silent…As if a brother had died.

Anna Akhmatova was born Anna Gorenko in Bolshoy Fontan on June 23, 1889 near Odessa, Ukraine. She began writing poetry at the age of 11, and adopted a pseudonym at the age of 17 to assuage her father’s fear of becoming a “decadent poetress.” The pseudonym was the Tartar name of Akhmatova’s great-grandmother. When she was sixteen her father abandoned his family. Still in her teens Akhmatova became a member of the Acmeist group of poets, whose leader, the poet and literature critic Nikolai Gumilov she married on April 10, 1910, in Kiev.

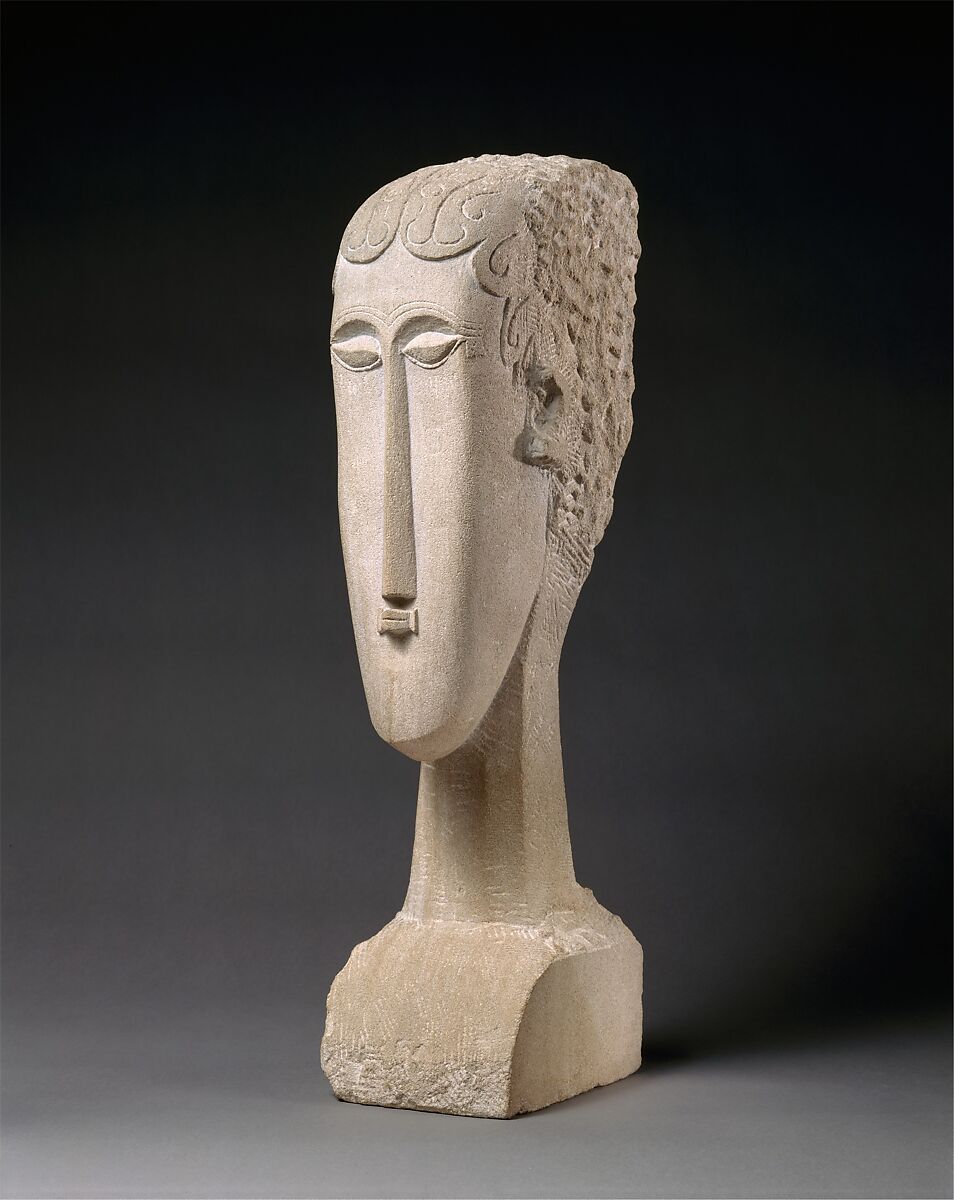

Amadeo Modigliani, Woman’s Head, 2012. In 1909, after meeting Constantin Brancusi, Modigliani began to produce sculptures by carving into stone, completing about twenty-five works throughout his short career. -The MET, NY

Their honeymoon was spent in Paris at a small apartment near Saint Sulpice on the left bank in Montparnesse where she was introduced to the young Italian painter Amedeo Modigliani. A jealous Gumilov was reported to have called Modigliani a “drunken monster” and soon left his young bride for Africa where he made multiple excursions eventually filling the St. Petersburg Museum of Ethnography with found rare artifacts. Their son Lev was born in 2012, and six years later they divorced. In 1921, Gumilov was caught in a counter-revolutionary plot and executed.

Akhmatova returned to Paris in 1911 where she and Modigliani fell in love and bonded over poetry. “He always had Les chants de Maldoror in his pocket,” she wrote, “this book at that time was a bibliographical rarity.” Maldoror, a darkly bizarre and decadent prose-poem by Comte de Lautréamont, which became a foundational text for the Surrealists and André Breton who called it “the expression of a total revelation which seems to exceed human possibilities.” Modigliani was raised in a progressive but impoverished Italian Jewish family in Livorno who encouraged his talent. As a youth he was drawn towards the philosophy of Nitzsche and Henri Bergson and believed artists needed to stay close to poverty and self-imposed torment to create. He moved to Paris in 1906 where his circle of friends and supporters included Chagall, Picasso, Max Jacob, Jacques Lipchitz, Chiam Soutine, and the sculptor Brancusi who became his mentor.

Akhmatova called Modigliani “god-like,” and described him as having “the head of an Antinous and eyes with sparks of gold— in appearance he was absolutely unlike anyone else. His voice remains engraved on my memory for ever. I knew he was poor, and no one knew what he lived on. As an artist, not a shadow of recognition.” Although she was only twenty at their first meeting, his presence remained a steady force throughout her life. In her memoir she wrote:

Whenever it rained (it often rained in Paris) Modigliani took with him a huge old black umbrella. We would sit together under this umbrella on a bench in the Jardin du Luxembourg in the warm summer rain. We would jointly recite Verlaine, whom we knew by heart, and we were glad we shared the same interests.

I remember a few sentences from his letters. Here is one of them: Vous êtes en moi comme une hantise [You are like an obsession in me]

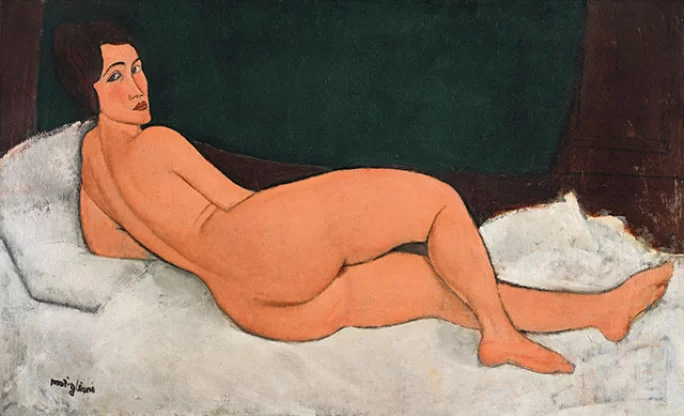

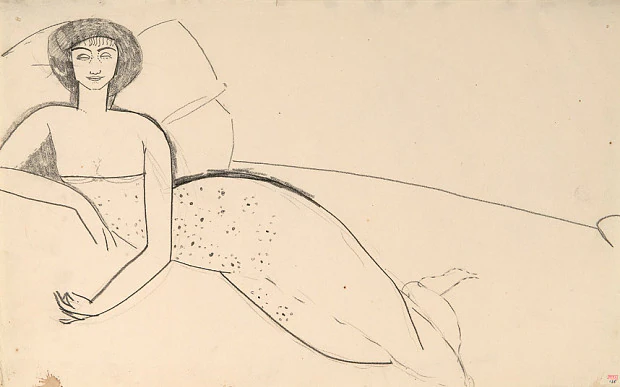

A ravishing beauty, the elegant, slim, six-foot tall Akhmatova had sad deep set grey-green eyes, pale skin, and dark hair. She stood nearly a foot taller than Modigliani and embodied his aesthetic ideal. He was inspired to draw sixteen portraits of Akhmatova, some of them nudes, and mostly from memory.

A favorite pastime for the couple was to stroll through the Egyptian and ancient art galleries of the Louvre. In one drawing, Modigliani portrayed the poetess as an Egyptian priestess in an exotic headdress with beads, a style she adopted and seen in later photographs. A very similar drawing, another elongated simplified portrait was kept throughout her life and reproduced on several book dust jackets.

Femme à la robe décolleté allongatée sur un lit, a portrait in black crayon of the artist’s lover, the fêted Russian poet Anna Akhmatova. Circa 1910-1911

Akhmatova described their relationship as being based in poetry. “Most of all we used to talk about poetry,” she wrote. “We both knew a great many French verses: by Verlaine, Laforgue, Mallarmé, Baudelaire.” They two identified as outsiders, even among the current avant-garde. Akhmatova recalled a poetic incident that happened while waiting for the artist outside his dismal garret.

One day there was a misunderstanding about our appointment and when I called for Modigliani, I found him out—but I decided to wait for him for a few minutes. I held an armful of red roses. The window, which was above the locked gates of the studio, was open. To while away the time, I started to throw the flowers into the studio. Modigliani didn’t come and I left.

When I met him, he expressed his surprise about my getting into the locked room while he had the key. I explained how it happened. “It’s impossible—they lay so beautifully.”

Modigliani liked to wander about Paris at night and often when I heard his steps in the sleepy silence of the streets, I came to the window and through the blinds watched his shadow, which lingered under my windows….

Modigliani focused on his unique figurative art at a time when cubism and abstraction was gaining traction. He was well-loved among fellow Parisian artists and an outpouring of international success followed after his death in 1920 from tubercular meningitis at the age of thirty-five. Akhmatova described him as a lonely stoic figure:

I felt he was surrounded by a solid ring of loneliness. I don’t remember him ever greeting anyone in the Luxembourg Gardens or the Latin Quarter—where everyone seemed to have a nodding acquaintance with each other. I never heard him mention anyone he knew, friend or painter. I never heard him make a joke. I never saw him drink, and his breath didn’t smell of wine. Obviously he began drinking at a later stage, but hashish had already made its appearance in the stories he told. At the time, openly at least, he had no woman companion. He never romanced (as everyone does, alas) about former loves. With me he didn’t usually talk about terre-à-terre things….His courtesy wasn’t the outcome of upbringing at home, but of his sublime spirit.

Akhmatova’s first collection of poetry, Evening appeared in 1912, followed by Rosary which brought her fame in 2014. “I filled the vacancy for a woman poet,” she said. Her 1911 poem ‘Love’ speaks to the passion and range of emotions that overcame her in Paris:

Now, like a little snake, it curls into a ball,

Bewitching your heart,

Then for days it will coo like a dove

On the little white windowsill.

Or it will flash as bright frost,

Drowse like a gillyflower…

But surely and stealthily it will lead you away

From joy and from tranquility.

It knows how to sob so sweetly

In the prayer of a yearning violin,

And how fearful to divine it

In a still unfamiliar smile.

Between 1924 and 1950 her work was censored and could no longer be read or published in Russia. She was beloved by the people but considered a political outcast due to her first marriage. In the 1950s she began publishing poems eulogizing Stalin in an attempt to set her son Lev free from a prison camp. After serving 15 years of hard labor he was finally released in 1956. Many of her closest friends where also unjustly imprisoned or murdered.

In her later years Akhmatova earned extra income by translating works of other writers, such as Victor Hugo, Rabindranath Tagore, and Giacomo Leopardi. She also wrote memoirs on Aleksandr Blok, Amedeo Modigliani, and Osip Mandelstam. From the mid-1950s onward Akhmatova gradually became reaccepted. In 1964 she won Taormina Poetry Prize and was allowed to travel to Italy to accept it.

Tomorrow, her children… O, what small things rest

For her to do on earth – only to play

With this fool, and the black snake to her dark breast

Indifferently, like a parting kindness, lay.

( Anna Akhmatova from ‘Cleopatra’)

Akhmatova’s third husband, Nikolai Punin, died in the 1950s in a Siberian camp. Nobel laureate Boris Pasternak proposed to Akhmatova several times and wrote a tribute ‘To Anna Akhmatova.’ The last stanzas read:

Eyesight can be sharp, differently,

form be precise in varying ways,

but a solvent of acid power’s

out there under the white night’s blaze.

That’s how I see your face and look.

Not that pillar of salt, in mind,

in which five years ago you fixed

our fears of looking behind.

From your first verses where grains

of clear speech hardened, to the last,

your eye, the spark that shakes the wire,

makes all things quiver with the past.

In a 1990 review The Sheer Necessity of Poetry New York Times reviewer John Baily wrote:

In 1962, four years before Akhmatova died at the age of 76, Robert Frost visited the Soviet Union and paid a call on her at the dacha lent her for the occasion at the writers’ colony near Leningrad. The two distinguished old poets sat side by side in wicker chairs and talked quietly. ”And I kept thinking,” Akhmatova wrote afterward, ”here are you, my dear, a national poet. Every year your books are published. . . . They praise you in all the newspapers and journals, they teach you in the schools, the President receives you as an honored guest. And all they’ve done is slander me! . . . I’ve had everything – poverty, prison lines, fear, poems remembered only by heart, and burnt poems. And humiliation and grief. And you don’t know anything about this and wouldn’t be able to understand it if I told you. . . . But now let’s sit together, two old people, in wicker chairs. A single end awaits us. And perhaps the real difference is not actually so great?”

But she knew it was. Great not so much in terms of suffering – bitter and prolonged as that had been – but in terms of the sheer necessity for poetry in such times, for the Russian poet and for his audience. In a happier country it is one of the amenities, not the needs. The culture that is optional and varied in a civilized society was for many in Stalin’s country the only way to stay living and sane.

For this reason the poet must never forget, or allow the new barbarism to blot out the past. Akhmatova saw her poetic role as one of remembering and bearing witness. As Roberta Reeder points out in her admirable introduction to ”The Complete Poems of Anna Akhmatova,”

”for Akhmatova, to forget was to commit a mortal sin. Memory had become a moral category: one remembers one’s misdeeds, atones, and achieves redemption.” And in those miserable years in which Soviet culture sought to impose a Communist stereotype on every aspect of society, the poet’s personal memories were as communally precious as statements bearing witness to public events and universal suffering. Akhmatova’a two great poems, ‘Requiem‘ and ‘Poem Without a Hero,’ record, respectively, the time of terror and the purges and a more timeless vision of the past in which the dead and the living meet and change roles, and key events in the poet’s own life become part of a public nightmare.

“…All the same, the five open a’s of Anna Akhmatova had a hypnotic effect and put this name’s carrier firmly on top of the alphabet of Russian poetry. In a sense, it was her first successful line; memorable in its acoustic inevitability, with its Ah sponsored less by sentiment than by history. This tells you a lot about the intuition and quality of the ear of this seventeen-year-old girl who soon after publication began to sign her letters and legal papers as Anna Akhmatova. In its suggestion of identity derived from the fusion of sound and time, the choice of the pseudonym turned out to be prophetic…”

-Joseph Brodsky

Please Note: All quotations from Akhmatova’s memoir of Modigliani are excerpted from the August 1964 edition of the London Magazine or from a translation found in the July 14, 1974 edition of The New York Review . Also in The New York Review of August 8, 1973, Nobel Prize winning Russian-American poet Joseph Brodsky wrote Translanting Akhmatova and had this to say on the apparent simplicity of her verse and the difficulty of translation:

I will allow myself a generalization. One of the main characteristics of Russian poetry is its restraint. Russian poets (I am speaking of the best of them) never allow themselves hysterics on paper, pathological confessions, spilling ashes over their heads, curses aimed at the guilty, no matter what the character of the events which they become witness to, participants in, or, sometimes, victims of. Akhmatova was a profound believer, and therefore she understood that, more or less, no one is guilty. Or more precisely, that the guilty exist, but that they are also human beings, just like their victims. I think that she knew the ambivalence of consciousness characteristic of all Russians. As a rule ambivalence leads to one of three things: cynicism, wisdom, or complete paralysis, i.e., an inability to act. Akhmatova achieved wisdom. Therefore her verse is extremely simple, restrained, and at times, like all real wisdom, it sounds banal. It is essential to understand this and then there will be no temptation to omit some things, emphasize others, use free verse where the original is in sestets, etc. That is, the translator must have not only the technical but also the spiritual experience of the original.

The Russian Poetry Net contains many examples and links to other Akhmatova sites: Northwestern University Akhmatova Page

A fine selection of poems is categorized by title and subject at: A Collection of Poems by Anna Akhmatova.