The photographer – and the consumer of photographs – follows in the footsteps of the ragpicker, who was one of Baudelaire’s favorite figures for the modern poet.–Susan Sontag, On Photography

Julia Reyes Taubman worked in semi-seclusion on her Detroit photography project for nearly seven years and after almost 40,000 photographs she’s assembled her first book with the help of former Detroit Free Press art critic Marsha Miro and book designer Lorraine Wild, a former Detroiter who endowed the book with its visual rhythms and focus. Wild is an award-winning book designer and her understated design and careful editorial eye brings the book to life.

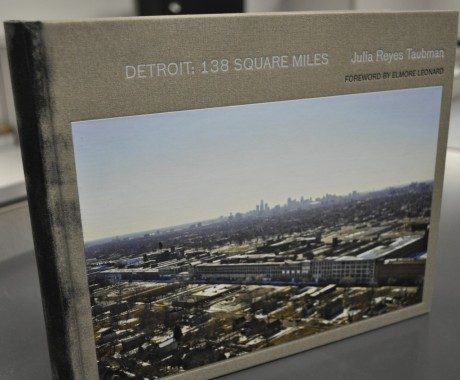

Wild builds a contemplative narrative and pacing structure for the mammoth 488 page book, framing the images into an almost cinematic jigsaw puzzle, from its 1970s’ conceptual-art cover with it’s dark burnished industrial-edged spine to its chapter divisions cataloged into East, Central and Western geographic regions. Photographs are strung together into clusters like a Greek chorus gathered together by style, size, or setting. Page layouts bounce off each other, overlapping and mirroring forms. Pages extend like a roadway into one another with borders continuing the skylines and horizons, with areas of pure white acting like rest stops. Visual music and poetry is in large evidence, the brilliance of the design sculpting the project into the category of “book as art object.”

Wild builds a contemplative narrative and pacing structure for the mammoth 488 page book, framing the images into an almost cinematic jigsaw puzzle, from its 1970s’ conceptual-art cover with it’s dark burnished industrial-edged spine to its chapter divisions cataloged into East, Central and Western geographic regions. Photographs are strung together into clusters like a Greek chorus gathered together by style, size, or setting. Page layouts bounce off each other, overlapping and mirroring forms. Pages extend like a roadway into one another with borders continuing the skylines and horizons, with areas of pure white acting like rest stops. Visual music and poetry is in large evidence, the brilliance of the design sculpting the project into the category of “book as art object.”

Beginning with the East is a shot of the Detroit river; blood current and namesake of the city. It’s a mysterious washed-out photograph, shrouded in fog, drifting off the page like the numinous seascapes of Hiroshi Sugimoto, balanced on the edge of life or death. The book moves forward and westward like a tiny child’s first steps, slowly, carefully, opening its eyes.

Punctuated by visual mysteries and alien landscapes, (a chair perched in a tree, an odd telephone glued to a tall pole, blue snaky hoses in a forest swamp, dark windowless biker bars, stained crack-house mattresses, gang graffiti and bizarre rubbish piles, homes turned inside-out) the book casts a labyrinthian quality as it passes through gray overcast winter skies, skeleton tree branches, and snow covered grass. The quietly surreal, bluesy and lonely nature of Detroit creates the perfect backdrop and subject matter for photographic inquiry.

Punctuated by visual mysteries and alien landscapes, (a chair perched in a tree, an odd telephone glued to a tall pole, blue snaky hoses in a forest swamp, dark windowless biker bars, stained crack-house mattresses, gang graffiti and bizarre rubbish piles, homes turned inside-out) the book casts a labyrinthian quality as it passes through gray overcast winter skies, skeleton tree branches, and snow covered grass. The quietly surreal, bluesy and lonely nature of Detroit creates the perfect backdrop and subject matter for photographic inquiry.

Detroit: 138 Square Miles reads like a visual journey through subterranean wastelands, a mythic travelogue through tightly knit neighborhoods, infernos, architectural masterworks, seedy bars and secret backroom locations. Photos from a low-flying airplane splash across pages like arial exclamation points, revealing rarely seen views of the city, showing in brilliant detail the vastness of its arterial rust and exposed nervous system.

In her 1953 non-fiction masterpiece, The Pleasure of Ruins, the late novelist Rose McCauley wrote, “Ruin is always overstated; it is part of the ruin-drama staged perpetually in the human imagination, half of whose desire is to build up, while the other half smashes and levels to the earth.” This volatile mixture of the sublime and ordinary, the historic and powerless, the built up and smashed, ignites an arresting condition between photographer and viewer.

The imagination is stirred by the contemplation of ruins as we cast ourselves inside the post-apocalyptic future of the present. History is never completely preserved or frozen by photographs. We are left with tracings from the past, fragments that form an ephemeral reality outside of our reach, a city of equal parts kitsch and perseverance. As observers we are caught inside the poetic paradox of the ruin and the photograph, a ruin in constant change, dissolution, romanticism and recovery. A “Renaissance City” spinning in eternal returns, destroying and resurrecting its symbolic city-image as the phoenix firebird.

Detroit: 138 Square Miles is equally autobiography and diary about its maker, as it is love-letter to the city. Taubman’s appreciation of modernist buildings and formalism are noted in abundance and revealed through her underground aesthetic. The photographer’s fascination with outsiders, rockers, criminals, urban hipsters, connect and syncopate with the outsized wildness of the city. Her story is also of an artistic identity crafted from her surroundings. The city’s isolation and despair is opened up and contrasted by public parks, museums, rock concerts, sports arenas, architectural details, and little known neighborhood folk-art curiosities. Taubman’s shared journey is not unlike Baudelaire’s conception of the flânuer: “To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world…” 138 Square Miles is not just another textbook on doomed Detroit landscapes, but also a compendium of a personal magical awareness; a private index with its own unique codes; a personal love affair of industry, architecture, and wandering.

Detroit: 138 Square Miles includes a warm reflective introduction by local legend Elmore “Dutch” Leonard. He states, “The reason I’m still here must lie in Julia’s pictures… there is beauty in despair and sometimes a glimmer of hope. ” – and in Jerry Herron’s introductory essay “Living With Detroit”, he states, “.. the truth of this place is not something you say or take home in an image, but something you do and keep on doing until you become part of the design.” Detroit citizens have an undying passion for their city and its history, reflected in a flood of Detroit-centered books recently published. Generous footnotes next to thumbnail prints in the back of the book fill in details and background history forming a well captioned book-inside-a-book. The printing quality compares with the best of any fine-art photography book published today, destined to provoke discussion on ruins and the post-apocalyptic cities we inhabit. A handsome addition to any collection on or about Detroit.

Detroit: 138 Square Miles includes a warm reflective introduction by local legend Elmore “Dutch” Leonard. He states, “The reason I’m still here must lie in Julia’s pictures… there is beauty in despair and sometimes a glimmer of hope. ” – and in Jerry Herron’s introductory essay “Living With Detroit”, he states, “.. the truth of this place is not something you say or take home in an image, but something you do and keep on doing until you become part of the design.” Detroit citizens have an undying passion for their city and its history, reflected in a flood of Detroit-centered books recently published. Generous footnotes next to thumbnail prints in the back of the book fill in details and background history forming a well captioned book-inside-a-book. The printing quality compares with the best of any fine-art photography book published today, destined to provoke discussion on ruins and the post-apocalyptic cities we inhabit. A handsome addition to any collection on or about Detroit.

The final photograph of the book is the gravestone of the great bluesman Son House, who spent his final years in semi-obscurity as a janitor in the Old Main building at Wayne State University. His immortal Dry Spell Blues could be a fitting epitaph and accompaniment to all the photographs:

“It has been so dry, you can make a powder house out of the world

Well, it has been so dry, you can make a powder house out of the world

And holler money mens, like a rattlesnake in his coil

I throwed up my hands, Lord, and solemnly swore

I have throwed up my hands, Lord, and solemnly swore

Well, ain’t no need of me changing towns, it’s the drought everywhere I go

It’s a dry old spell everywhere I been

Oh, it’s a dry old spell everywhere I been

I believe to my soul this old world is bound to end

Well I stood in my backyard, wrung my hands and screamed

I stood in my backyard, I wrung my hands and screamed

And I couldn’t see nothing, couldn’t see nothing green

Oh Lord have mercy if you please

Oh Lord have mercy if you please

Let your rain come down and give our poor hearts ease

These blues, these blues is worthwhile to be heard

Oh, these blues is worthwhile to be heard

For it’s very likely bound to rain somewhere …”

—Dry Spell Blues, Son House

Copies of Detroit” 138 Square Miles are available at Book Beat (248) 968-1190 or online at our Backroom Gallery.

A limited number of Julia Reyes Taubman signed copies are available, please inquire.

This is a great article. I came across her website but wasn’t sure if I wanted to buy the book. This site gives the audience an insight from the photographer’s perspective. http://detroit138squaremiles.com/julia-taubman-captivated-detroit Julia Taubman seems to be really passionate about her work and reading this article makes me want to buy the book!